ideas

In philosophy of mind, a “cerebroscope” is a fictitious device, a brain–computer interface in today’s language, which reads out the content of somebody’s brain. An autocerebroscope is a device applied to one’s own brain. You would be able to see your own brain in action, observing the fleeting bioelectric activity of all its nerve cells and thus of your own conscious mind. There is a strange loopiness about this idea. The mind observing its own brain gives rise to the very mind observing this brain. How will this weirdness affect the brain? Neuroscience has answered this question more quickly than many thought possible.

But first, a bit of background. Epileptic seizures—hypersynchronized, self-maintained neural discharges that can sometimes engulf the entire brain—are a common neurological disorder. These recurring and episodic brain spasms are kept in check with drugs that dampen excitation and boost inhibition in the underlying circuits. Medication does not always work, however. When a localized abnormality, such as scar tissue or developmental miswiring, is suspected of triggering the seizure, neurosurgeons may remove the offending tissue. (…)

Under Fried’s supervision, a group from my laboratory—Rodrigo Quian Quiroga, Gabriel Kreiman and Leila Reddy—discovered a remarkable set of neurons in the jungles of the medial temporal lobe, the source of many epileptic seizures. This region, deep inside the brain, which includes the hippocampus, turns visual and other sensory percepts into memories.

We enlisted the help of several epileptic patients. While they waited for their seizures, we showed them about 100 pictures of familiar people, animals, landmark buildings and objects. We hoped one or more of the photographs would prompt some of the monitored neurons to fire a burst of action potentials. Most of the time the search turned up empty-handed, although sometimes we would come upon neurons that responded to categories of objects, such as animals, outdoor scenes or faces in general. But a few neurons were much more discerning. One hippocampal neuron responded only to photos of actress Jennifer Aniston but not to pictures of other blonde women or actresses; moreover, the cell fired in response to seven very different pictures of Jennifer Aniston. (…)

Nobody is born with cells selective for Jennifer Aniston. (…) The networks in the medial temporal lobe recognize such repeating patterns and dedicate specific neurons to them. You have concept neurons that encode family members, pets, friends, co-workers, the politicians you watch on TV, your laptop, that painting you adore.

Conversely, you do not have concept cells for things you rarely encounter.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

ideas, neurosciences | April 6th, 2011 6:00 pm

I was in the middle of teaching the difference between knowledge and belief when my cell phone buzzed in my pocket. It was a call from the dean of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas College of Liberal Arts.

The dean informed me that he was very sorry but, barring an unlikely immediate solution to the state’s financial crisis, the university had decided to eliminate the Philosophy Department, which I chair.

In July, I would be given a one-year terminal contract. After that, the university would fire me, along with all of my departmental colleagues, after twenty years of service.

{ The Boston Review | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, vegas | April 6th, 2011 6:00 pm

Alvin Roth spent years writing academic papers about the medical job market — specifically, picking apart the national system that matched young doctors to their first hospital jobs out of medical school. (…)

When it was introduced in the 1950s, the National Resident Matching Program was supposed to help doctors with the stressful and chaotic problem of finding their hospital internships. But after four decades, it was showing its age. Some medical students complained that the process was unfair, and that hospitals were being given too much power in determining where new doctors would live and work. Above all, the system was faltering because it was designed at a time when virtually no women became doctors, which meant it couldn’t handle married couples applying simultaneously. The result was that young doctors were passing up job opportunities for family reasons, and in some cases husbands and wives were assigned to distant cities and asked to choose their careers over each other.

As a professor who specialized in game theory, Roth had been studying medical matching programs closely since the early 1980s, figuring out what worked and what didn’t, and what rules were required to make a system in which everyone — the hospitals, the doctors — ended up happiest. He had coauthored a book full of theories and equations related to the problem of matching in general. He was so well known for this, one colleague remembers, that medical students would call him every year for advice on how to game the system. (…)

Roth has emerged as a rare figure in the academic world: a theorist willing to dive into real-world problems and fix them. After helping the med students, he designed a better way to assign children to public schools — the system now used by both Boston and New York. He also helped invent a system for matching kidney donors with patients, dramatically increasing the number of donations that take place each year.

{ The Boston Globe | Continue reading }

U.S., economics, health, ideas | April 6th, 2011 5:30 pm

What all media, all representations—from street signs to photographs to emoticons—have in common is this: they pay attention to you, they address you. Sometimes generically, as with street signs, sometimes precisely, as with person-specific ring tones. And all that attention is flattering—indeed, it is a form of flattery so pervasive, and so essential to the nature of representation, that it has escaped notice as such, though it ultimately accounts for the oft-remarked narcissism of our time. The very process by which reality and representation become fused in the age of the simulacrum is delivered to our psyches by the flattery of representation. We have been consigned by it to a new plane of being, a new kind of life-world, an environment of representations of fabulous quality and inescapable ubiquity, a place where everything is addressed to us, everything is for us, and nothing is beyond us anymore. (…)

In a mediated world, the opposite of real isn’t phony or artificial—it’s optional.

{ On the Politics of Pastiche and Depthless Intensities: The Case of Barack Obama | Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture | Continue reading }

photo { Todd Fisher }

ideas | April 4th, 2011 5:00 pm

If you can be sure of one thing, then surely it is that you exist. Even if the world were a dream or a hallucination, it would still need you to be dreaming or hallucinating it. (…)

There is a wide range of scientific evidence that is used to deny “I think, therefore I am”. In René Descartes’ famous deduction, a coherent, structured experience of the world is inextricably linked with a sense of a self at the heart of it. But as the clinical neuropsychologist Paul Broks explained to me, we now know the two can in fact be separated.

People with Cotard’s syndrome, for instance, can think that they don’t exist, an impossibility for Descartes. Broks describes it as a kind of “nihilistic delusion” in which they “have no sense of being alive in the moment, but they’ll give you their life history”. They think, but they do not have sense that therefore they are.

Then there is temporal lobe epilepsy, which can give sufferers an experience called transient epileptic amnesia. “The world around them stays just as real and vivid – in fact, even more vivid sometimes – but they have no sense of who they are,” Broks explains. This reminds me of Georg Lichtenberg’s correction of Descartes, who he claims was entitled to deduce from “I think” only the conclusion that “there is thought”. This is precisely how it can seem to people with temporal lobe epilepsy: there is thought, but they have no idea whose thought it is.

{ The Independent | Continue reading }

photo { Noritoshi Hirakawa }

ideas, psychology | April 2nd, 2011 1:57 pm

In the 2006 movie, Borat: Cutural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, English comedian Sacha Baron Cohen plays the role of an outrageously inappropriate Kazakh television reporter who journeys across the United States to film a documentary about American culture. In the course of his travels, the title character uses his bizarre persona to elicit offensive statements and behavior from, as well as to generally humiliate, a number of ordinary Americans who are clearly not in on the joke. How did the producers convince these unfortunate stooges to participate in the project? According to several who later sued, the producers lied about the identity of Borat and the nature of the movie when setting up the encounters in advance over the telephone, and they then contradicted and disclaimed the lies in a waiver that the stooges signed without reading just before the cameras began to roll.

This talk article explains the doctrinal and normative reasons that the Borat problem, which arises frequently, although usually in more mundane contexts, divides courts. It then suggests an approach for courts to use when facing the problem that minimizes risks of exploitation and costs of contracting.

{ The ‘Borat’ Problem and the Law of Negotiation | Continue reading }

photo { Alpines, the Night Drive EP, 500 individually numbered 10″ Vinyl Discs }

ideas, law, showbiz | April 2nd, 2011 1:50 pm

During the late Victorian period British women maintained a significant numerical advantage over men such that “almost one in three of all adult women were single and one in four would never marry.” Therefore it is no coincidence that spinsters “provided the backbone” of the women’s suffrage movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. These spinster-led feminists opposed patriarchal exploitation and challenged “the idea that male sexuality was a powerful and uncontrollable urge,” and in the course of their activism drew much needed attention to other related problems such as prostitution and the abuse of girls. But by presenting such resistance to the status quo their rising success roused an equally powerful countervailing enemy whose rise to power was intimately connected to the proponents of the “sexual revolution” that came to fruition in the 1920s.

{ Swans| Continue reading }

flashback, ideas, relationships | March 31st, 2011 6:37 pm

The annals of business history are full of tales of companies that once dominated their industries but fell into decline. The usual reasons offered don’t fully explain how the leaders who had steered these firms to greatness lost their touch.

In this article we argue that success can breed failure by hindering learning at both the individual and the organizational level. We all know that learning from failure is one of the most important capacities for people and companies to develop. Yet surprisingly, learning from success can present even greater challenges.

{ Harvard Business Review | Continue reading }

photo { Horace Vernet, Mazeppa and the Wolves, 1826 }

economics, ideas | March 31st, 2011 5:36 pm

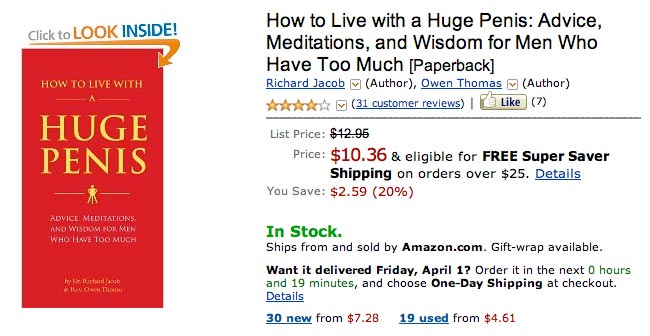

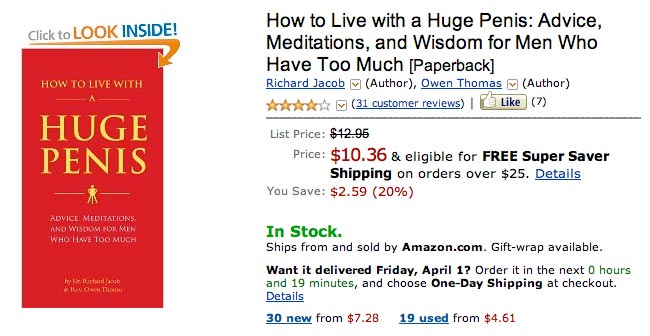

I have always suffered with having a (my girlfriend calls it) gi-normous penis. Imagine have two soda cans duct tapped together in your pants. I have always had a hard time sitting down and forget about it if I have an erection. (…) Have you ever been asked to GO HOME from your boss because you were distracting co-workers?

{ Amazon.com | Comments }

books, haha | March 31st, 2011 5:30 pm

Waiting is the period we endure until the expected happens. We wait for all sorts of things: the bus, dinner, colleagues who are late for a meeting, the rain to stop, etc. Waiting is built into our social lives. And our waiting behavior is influenced by a fair number of variables. There isn’t a prescribed method for waiting, and yet waiting in certain contexts tends toward a similar pattern of group impatience leading to aggressive strategies that are meant to better position the waiting individual for the event.

It may be that people are responding to a need to defend their territory. Territories are defined as areas that are controlled through established boundaries that are defended as necessary. There are private and public territories. Homes are private territories that are largely controlled by residents with little to no challenge for ownership from outside parties. However public territories, such as waiting rooms and phone booths, are temporary territories where “ownership” or residence may be challenged simply by the presence of others.

Researchers Ruback, Pape, and Doriot report that traditionally people appear to leave an area more quickly when the space around them has been “invaded.” For example, people tend to cross the street faster when grouped with strangers (perhaps this explains New Yorkers’ tendency for speed walking?), and researchers have found that library patrons will change seats or leave if strangers sit at the same table.

{ Anthropology in Practice | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | March 30th, 2011 7:29 pm

Many people like mathematics because it gives definite answers. Things are either true or false, and true things seem true in a very fundamental way.

The fact is, however, that mathematics has been moving on somewhat shaky philosophical ground for some time now. With the work of the logician Kurt Gödel and others in the 1930s it became clear that there are limits to the power of mathematics to pin down truth. In fact, it’s possible to build different versions of mathematics in which certain statements are true or false depending on your preference. This raises the possibility that mathematics is little more than a game in which we choose the rules to suit our purpose.

{ Plus mag | Continue reading }

related { Researchers have found a fractal pattern underlying everyday math. In the process, they’ve discovered a way to calculate partition numbers, a challenge that’s stymied mathematicians for centuries. | Wired | full story }

ideas, mathematics | March 30th, 2011 7:29 pm

Language, according to Benveniste, is the only semiotic system capable of interpreting another semiotic system. How, then, does language manage when it has to interpret music? Alas, it seems, very badly. If one looks at the normal practice of music criticism (or, which is often the same thing, of conversations “on” music), it can readily be seen that a work (or its performance) is only ever translated into the poorest of linguistic categories: the adjective. Music, by natural bent, is that which at once receives an adjective.

The adjective is inevitable: this music is this, this execution is that. No doubt the moment we turn an art into a subject (for an article, for a conversation) there is nothing left but to give it predicates; in the case of music, however, such predication unfailingly takes the most facile and trivial form, that of the epithet. Naturally, this epithet, to which we are constantly led by weakness or fascination (little parlour game: talk about a piece of music without using a single adjective), has an economic function: the predicate is always the bulwark with which the subject’s imaginary protects itself from the loss which threatens it. The man who provides himself or is provided with an adjective is now hurt, now pleased, but always constituted.

{ Roland Barthes, The Grain of the Voice, | Continue reading }

music, roland barthes | March 29th, 2011 8:27 pm

The nature of complexity is different in the economic realm from that in physical systems because it can stem from people gaming, from changing the rules and assumptions of the system. Ironically, “game theory” is not suited to addressing this source of complexity. But military theory is. (…)

Game theory began with the insights of John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern in their book, The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. They defined a game as an interaction between agents governed by a set of rules that specified possible moves for each participant and the set of outcomes for each possible set of moves. The theory of games rests on defined rules and outcomes. It also assumes rationality. “Rational” means “logical.” (…)

The military theorist John Boyd used this phrase to convey the essential point that warfare is not a game. Or if you want to think of it as a game, it is a game that is ill-defined, with rules that are, put gently, subject to interpretation. Thus, he said, for any strategy, “if it works, it is obsolete. Yesterday’s rules won’t work today”. This point was also made by the great German Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke: “In war as in art there exist no general rules; in neither can talent be replaced by precept.” That is, plans – and models – don’t work because the enemy does not cooperate with the assumptions on which they are based. In fact the enemy tries to discover and actively undermine any assumptions of his opponent.

{ Rick Bookstaber | Continue reading }

ideas | March 29th, 2011 8:02 pm

If photography is to be discussed on a serious level, it must be described in relation to death. It’s true that a photograph is a witness, but a witness of something that is no more. Even if the person in the picture is still alive, it’s a moment of this subject’s existence that was photographed, and this moment is gone. This is an enormous trauma for humanity, a trauma endlessly renewed. Each reading of a photo and there are billions worldwide in a day, each perception and reading of a photo is implicitly, in a repressed manner, a contract with what has ceased to exist, a contract with death.

{ Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida }

photo { John Gutmann }

photogs, roland barthes | March 29th, 2011 7:43 pm

For 40 years, psychologists thought that humans and animals kept time with a biological version of a stopwatch. Somewhere in the brain, a regular series of pulses was being generated. When the brain needed to time some event, a gate opened and the pulses moved into some kind of counting device.

One reason this clock model was so compelling: Psychologists could use it to explain how our perception of time changes. Think about how your feeling of time slows down as you see a car crash on the road ahead, how it speeds up when you’re wheeling around a dance floor in love. Psychologists argued that these experiences tweaked the pulse generator, speeding up the flow of pulses or slowing it down.

But the fact is that the biology of the brain just doesn’t work like the clocks we’re familiar with. Neurons can do a good job of producing a steady series of pulses. They don’t have what it takes to count pulses accurately for seconds or minutes or more. The mistakes we make in telling time also raise doubts about the clock models. If our brains really did work that way, we ought to do a better job of estimating long periods of time than short ones. Any individual pulse from the hypothetical clock would be a little bit slow or fast. Over a short time, the brain would accumulate just a few pulses, and so the error could be significant. The many pulses that pile up over long stretches of time should cancel their errors out. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. As we estimate longer stretches of time, the range of errors gets bigger as well.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

neurosciences, time | March 28th, 2011 5:48 pm

{ Ezra Stoller | Top: Seagram Building, Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson, New York, NY, 1958 | Bottom: General Motors Technical Center, Eero Saarinen, Warren, MI, 1950 | Yossi Milo Gallery, NYC | more }

related { At about 3.45pm, witnesses recalled, Barthes paused before crossing the street at 44 rue des Écoles; he looked left and right, but failed to spot an advancing laundry van, which knocked him down. | Rereading: Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes | Roland Barthes, Camera lucida: reflections on photography, 1981 | Google Books }

photogs, roland barthes | March 28th, 2011 5:45 pm

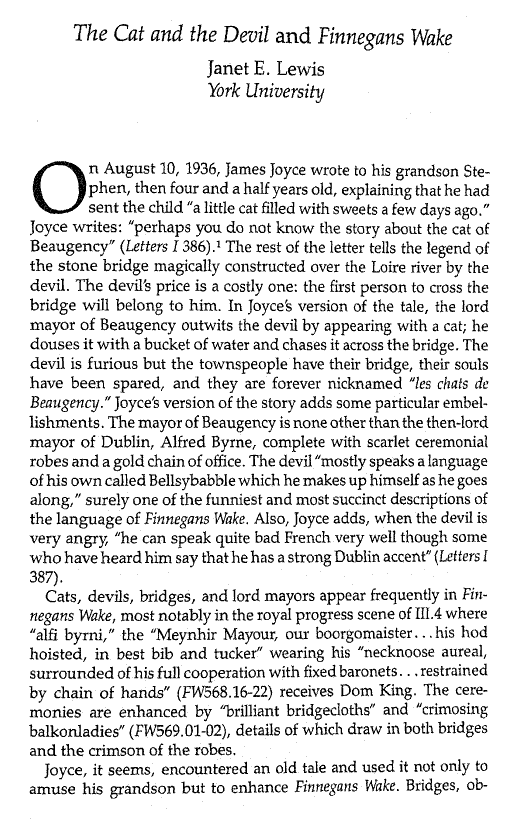

James Joyce, animals, books | March 25th, 2011 9:34 am

A study using census data from nine countries shows that religion there is set for extinction, say researchers.

The study found a steady rise in those claiming no religious affiliation.

The team’s mathematical model attempts to account for the interplay between the number of religious respondents and the social motives behind being one.

The result, reported at the American Physical Society meeting in Dallas, US, indicates that religion will all but die out altogether in those countries.

The team took census data stretching back as far as a century from countries in which the census queried religious affiliation: Australia, Austria, Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Switzerland.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

ideas, within the world | March 23rd, 2011 4:43 pm

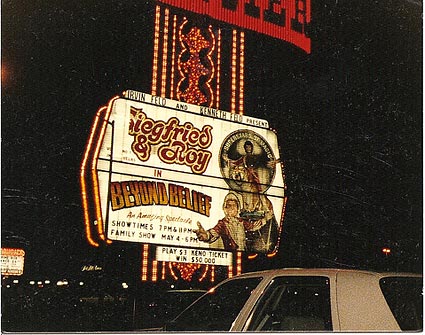

Forty years ago, on March 21, 1971, Hunter S. Thompson and a Chicano activist attorney named Oscar Zeta Acosta drove from Los Angeles to Las Vegas to talk over an article Thompson was writing about the barrios of East L.A. When the account of their journey appeared in Rolling Stone in November of that year, Thompson and Acosta had morphed into Raoul Duke and his 300-pound Samoan attorney and the trunk of their car, the Great Red Shark, had become a rolling drug dispensary. (…)

Fear and Loathing compresses two separate trips Thompson took to Las Vegas that spring – the first to cover a motorcycle race called the Mint 400, the second to cover the National District Attorneys’ Conference on Drug Abuse – into a single hellish week of drug consumption and debauchery.

{ The Millions | Continue reading }

On 29 April 1971, Thompson began writing the full manuscript in a hotel room in Arcadia, California, in his spare time. (…)

In November 1971, Rolling Stone published the combined texts of the trips as Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream as a two-part article illustrated by Ralph Steadman. (…)

The New York Times said it is “by far the best book yet on the decade of dope.”

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Thompson and Acosta, 1971 }

books, drugs | March 22nd, 2011 8:05 pm

When we hear the word “universe,” we think that means everything: every star, every galaxy, everything that exists. But in physics, we’ve come upon the possibility that what we’ve long thought to be everything may actually only be a small part of something that is much, much bigger. The word “multiverse” refers to that bigger expanse, the new totality of reality, and our universe would be just a piece of that larger whole.

Scientists have many proposals. In some, the other universes have the same laws of physics and the same particles making up matter. So except perhaps for some environmental differences, pretty much what we see here is what happens there. In some multiverse proposals, the other universes could be radically different from what we know, the particles could be different, the laws of physics could appear different. And in others—ones that frankly don’t compel me—even the kinds of mathematics that govern the physics in those realms might be different from the math that we are familiar with.

{ Research/Columbia University | Continue reading }

image { Mars and Beyond, Disney, 1957 }

ideas, space | March 22nd, 2011 7:07 pm