ideas

What’s the tradeoff between people using their experience (people using the knowledge they’ve gained, and the expertise that they’ve developed), versus being able to just follow steps and procedures?

We know from the literature that people sometimes make mistakes. A lot of organizations are worried about mistakes, and try to cut down on errors by introducing checklists, introducing procedures, and those are extremely valuable. I don’t want to fly in an airplane with pilots who have forgot their checklists. (…)

How do people make the tradeoffs when they start to become experts? And does it have to be one or the other? Do people either have to just follow procedures, or do they have to abandon all procedures and use their knowledge and their intuition?

This gets us into the work on system one and system two thinking.

System one is really about intuition, people using the expertise and the experience they’ve gained. System two is a way of monitoring things, and we need both of those, and we need to blend them.

{ Edge | Continue reading }

ideas | July 8th, 2011 5:49 pm

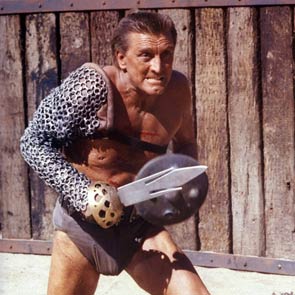

I have been reading Curzio Malaparte’s Technique of the Coup d’état this weekend. It’s a fascinating document – the basic argument is that the October Revolution represented an exportable, universally applicable technology for taking control of the state, quite independent of ideological motivation or broader strategic situation. (…)

So, what’s this open-source putsch kit consist of? Basically you need a small force of determined rebels. Small is important – you want quality not quantity as secrecy, unanimity, and common understanding good enough to permit independent action are required. You want as much chaos as possible in advance of the coup, although not so much that everything’s shut. And then you occupy key infrastructures and command-and-control targets. Don’t, whatever you do, go after ministries or similar grand institutional buildings – get the stuff that would really cause trouble if it blew up.

{ The Yorkshire Ranter | Continue reading }

guide, ideas, incidents | July 8th, 2011 5:15 pm

As a shy person, I’ve believed for most of my life that being among new people required an elaborate social disguise, one that would allow me to feel both present and absent, noticed and unnoticed. I’d yearn for some sort of social recognition without the bother of having to be recognized, without that oppressive pressure to live up to anything that might get me attention in the first place. So I’d find myself executing oblique tactics — being stingy and stealthy with eye contact; wearing a mask of deep concentration; staring at an underappreciated object in the room, like a light fixture or molding — in hopes of discouraging people from engaging me in actual conversation while still conveying the impression that I might be interesting to talk to.

The problem with polite conversation, I thought, was that it required the orderly recitation of platitudes before one can say anything interesting, let alone something as original and insightful as I wanted to believe myself to be. I couldn’t bear it. I had an irrational expectation that people should already know what I was about and come to me with suitable topics to draw me out.

{ Rob Horning /The New Inquiry | Continue reading | image: Thanks Rachel! }

experience, ideas, relationships | July 8th, 2011 5:06 pm

So what is financial engineering? In a logically consistent world, financial engineering should be layered above a solid base of financial science. Financial engineering would be the study of how to create functional financial devices – convertible bonds, warrants, synthetic CDOs, etc. – that perform in desired ways, not just at expiration, but throughout their lifetime. That’s what Black-Scholes does – it tells you, under certain assumptions, how to engineer a perfect option from stock and bonds.

But what exactly is financial science?

Canonical financial engineering or quantitative finance rests upon the science of Brownian motion and other idealizations that, while they capture some of the essential features of uncertainty, are not finally very accurate descriptions of the characteristic behavior of financial objects. (…) Markets are filled with anomalies that disagree with standard theories. Stock evolution, to take just one of many examples, isn’t Brownian. We don’t really know what describes its motion. Maybe we never will. And when we try to model stochastic volatility, it’s an order of magnitude vaguer. (…)

If you’re going to work in this field, you have to understand that you’re not doing classical science at all, and that the classical scientific approach doesn’t have the unimpeachable value it has in the hard sciences.

{ Emanuel Derman/Reuters | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, science | July 8th, 2011 4:38 pm

Everything we do is for the purpose of altering consciousness. We form friendships so that we can feel certain emotions, like love, and avoid others, like loneliness. We eat specific foods to enjoy their fleeting presence on our tongues. We read for the pleasure of thinking another person’s thoughts. Every waking moment—and even in our dreams—we struggle to direct the flow of sensation, emotion, and cognition toward states of consciousness that we value.

Drugs are another means toward this end. Some are illegal; some are stigmatized; some are dangerous—though, perversely, these sets only partially intersect. There are drugs of extraordinary power and utility, like psilocybin (the active compound in “magic mushrooms”) and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which pose no apparent risk of addiction and are physically well-tolerated, and yet one can still be sent to prison for their use—while drugs like tobacco and alcohol, which have ruined countless lives, are enjoyed ad libitum in almost every society on earth. There are other points on this continuum—3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or “Ecstasy”) has remarkable therapeutic potential, but it is also susceptible to abuse, and it appears to be neurotoxic.

{ Sam Harris | Continue reading }

drugs, ideas | July 8th, 2011 9:20 am

Among ethical concepts, conscience is a remarkable survivor. During the 2000 years of its existence it has had ups and downs, but has never gone away. Originating as Roman conscientia, it was adopted by the Catholic Church, redefined and competitively claimed by Luther and the Protestants during the Reformation, adapted to secular philosophy during the Enlightenment, and is still actively abroad in the world today. Yet the last few decades have been cloudy ones for conscience, a unique time of trial.

The problem for conscience has always been its precarious authorization. It is both a uniquely personal impulse and a matter of institutional consensus, a strongly felt personal view and a shared norm upon which all reasonable or ethical people are expected to agree. As a result of its mixed mandate, conscience performs in differing and even contradictory ways.

{ Paul Strohm/OUP | Continue reading }

related { Can data determine moral values? }

photo { Uri Korn }

ideas, photogs, psychology | July 6th, 2011 6:35 pm

On 7 July 1688 the Irish scientist and politician William Molyneux (1656–1698) sent a letter to John Locke in which he put forward a problem which was to awaken great interest among philosophers and other scientists throughout the Enlightenment and up until the present day. In brief, the question Molyneux asked was whether a man who has been born blind and who has learnt to distinguish and name a globe and a cube by touch, would be able to distinguish and name these objects simply by sight, once he had been enabled to see. (…)

For reasons unknown Locke never replied to the letter.

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

artwork { Alan Bur Johnson }

flashback, ideas | July 5th, 2011 3:33 pm

Geographical metaphors such as centre-periphery or First-Second-Third World are widely used to describe the world economic system. This paper discusses the role of metaphors in geographical representations and proposes some guidelines for the analysis and classification. This methodology is then applied to a sample of well known textual metaphors used to describe the world economic scenario, including ideas of a First-Second-Third World, North-South, core-periphery, Global Triad, global network, flat and fluid world. The classification is linked to the debates originating such metaphors, and it will be used in order to propose some concluding remarks on the possibility of development of new geographical metaphors.

{ SSRN | Continue reading }

ideas | July 5th, 2011 3:33 pm

It is hard to think of another writer as great as Mark Twain who did so many things that even merely good writers are not supposed to do. Great writers are not meant to write bad books, much less publish them. Twain not only published a lot of bad books, he doesn’t appear to have noticed the difference between his good ones and his bad ones. Great writers are not meant to care more about money than art. Twain cared so much about money that what little he writes about his art in his autobiography is almost entirely, and obsessively, about the business end of things: his paychecks, his promotional tours, his financial disputes with publishers, his venture capital investments in publishing and printing technology. He stops and starts Huckleberry Finn over and again to devote vast amounts of his time and energy to losing $190,000 (roughly $4 million today) in a doomed typesetting machine, and nearly bankrupts himself. Great writers are expected to be interested in ideas; they should associate themselves with at least a few convictions. Apart from a frontier notion of freedom, Twain never met an idea he could not reduce to a joke. He doesn’t even appear to have been wedded to his own skepticism. (…)

Everywhere he went, including the White House, he was always the biggest star in the room. (…)

Twain mentions that in the good old days the post office delivered him a letter from Europe at his home in Hartford, Connecticut, addressed to:

Mark Twain

God Knows Where

{ Michael Lewis/The New Republic | Continue reading }

books | July 5th, 2011 3:32 pm

Sense-perception—the awareness or apprehension of things by sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste—has long been a preoccupation of philosophers. One pervasive and traditional problem, sometimes called “the problem of perception”, is created by the phenomena of perceptual illusion and hallucination: if these kinds of error are possible, how can perception be what it intuitively seems to be, a direct and immediate access to reality? The present entry is about how these possibilities of error challenge the intelligibility of the phenomenon of perception, and how the major theories of perception in the last century are best understood as responses to this challenge.

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

Phenomenology is the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, its being directed toward something, as it is an experience of or about some object. An experience is directed toward an object by virtue of its content or meaning (which represents the object) together with appropriate enabling conditions.

Phenomenology as a discipline is distinct from but related to other key disciplines in philosophy, such as ontology, epistemology, logic, and ethics. Phenomenology has been practiced in various guises for centuries, but it came into its own in the early 20th century in the works of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty and others. Phenomenological issues of intentionality, consciousness, qualia, and first-person perspective have been prominent in recent philosophy of mind. (…)

The Oxford English Dictionary presents the following definition: “Phenomenology. a. The science of phenomena as distinct from being (ontology). b. That division of any science which describes and classifies its phenomena. From the Greek phainomenon, appearance.” In philosophy, the term is used in the first sense, amid debates of theory and methodology. In physics and philosophy of science, the term is used in the second sense, albeit only occasionally.

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

Linguistics, ideas | July 1st, 2011 8:18 pm

Enthusiasm for The Wire is hardly limited to law professors, but the series does seem to hold a special appeal for us, especially if we teach criminal law and criminal procedure. What accounts for that appeal? Not, I think, the widely praised realism of The Wire, at least not in the most obvious ways. The series does have an almost visceral sense of place, and it does show, in grim detail, many of the ways the criminal justice system goes wrong. But the loving attention to Baltimore does little to explain the particular pull the series has for those of us who teach and write about criminal justice, and the institutional failures that the series spotlights—the futility of the war on drugs, the cooking of crime statistics, the often casual brutality of street-level policing—are, let’s face it, hardly news. Even among law professors, it’s hard to imagine any documentary about those failures, no matter how accurate, generating the kind of excitement The Wire has generated.

It has to be said, too, that there are important ways in which The Wire isn’t all that realistic. It is not particularly good, for example, at capturing the workaday feel of law enforcement. Any number of less celebrated television programs—Barney Miller, Cagney & Lacey, Hill Street Blues, even Law & Order—have done a better job of that. Nor, for the most part, does The Wire seem especially perceptive about leadership. The organizational dynamics of law enforcement, and the compromised politics of city government, often have a crazed, over-the-top feel in the series—entertaining, but not strikingly true to life. In these respects, and some others, The Wire aims less for verisimilitude than for the power of myth.

Nonetheless much of what makes The Wire so gripping—and, I think, much of what makes it especially gripping for professors of criminal law and criminal procedure—does seem to have to do with a certain kind of realism. It isn’t detailed accuracy about institutional failures, or the drug trade, or post-9/11 Baltimore, but something at once bigger and more basic: the dimensions of human and moral complexity that criminal justice work, in pretty much any time or place, will inevitably bring to the surface.

{ David Alan Sklansky, Confined, Crammed, and Inextricable: What The Wire Gets Right, 2011 | SSRN | Continue reading }

ideas, showbiz | July 1st, 2011 4:37 pm

Each culture has its agreed-upon list of taboo words and it doesn’t matter how many times these words are repeated, they still seem to retain their power to shock. Scan a human brain, swear at it, and you’ll see its emotional centres jangle away.

Recent research has shown that this emotional impact can have an analgesic effect, and there’s other evidence that strategically deployed swear words can make a speech more memorable. But it’s not all positive. A new study suggests that swear words have a dark side. Megan Robbins and her team recorded snippets of speech from middle-aged women with rheumatoid arthritis, and others with breast cancer, and found those who swore more in the company of other people also experienced increased depression and a perceived loss of social support.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

photo { Calvin Sawer }

Linguistics, health, psychology | July 1st, 2011 4:25 pm

One way to study a network is to break it down into its simplest pattern of links. These simple patterns are called motifs and their numbers usually depend on the type of network.

One of the big puzzles of network science is that some motifs crop up much more often than others. These motifs are clearly important. Remove them (or change their distribution) and the behaviour of the network changes too. But nobody knows why.

Today, Xiao-Ke Xu at Hong Kong Polytechnic University and friends say they know why and the answer is intimately linked to the existence of rich clubs within a network.

Let’s step back for a bit of background. In many networks, a small number of nodes are well connected to large number of others. The group of all well-connected nodes is known as the “rich club” and it is known to play an important role in the network of which it is part.

Rich clubs are particularly influential in a specific class of network in which the number of links between nodes varies in a way that is scale free (ie follows a power law).

This is an important class. It includes the internet, social networks, airline networks and many naturally occurring networks such as gene regulatory networks.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

photo { Jimi Franklin }

ideas, science, technology | July 1st, 2011 4:22 pm

University of Oxford Writing and Style Guide decided that writers should, “as a general rule,” avoid using the Oxford comma.

Here’s an explanation from the style guide: As a general rule, do not use the serial/Oxford comma: so write ‘a, b and c’ not ‘a, b, and c.’

{ GalleyCat | Continue reading }

Linguistics | July 1st, 2011 3:59 pm

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness, the causes of which are not yet well understood. It afflicts about 1% of the population, typically emerging in late adolescence or early adulthood. Neuroimaging and functional testing identify diminished brain volume in key areas and declining cognitive and social functioning at the time that symptoms of the disease emerge. After onset, the symptoms persist, although their intensity fluctuates and some long-term research has identified patients in whom symptoms have dissipated many years after onset. Psychotropic drugs relieve symptoms such as hallucinations and paranoid delusions for some patients, but they have no effect on cognitive or social functioning.

{ Housing and Mental Illness | Harvard University Press | Continue reading }

artwork { Izumi Kato }

health, ideas, neurosciences | June 29th, 2011 4:00 pm

We don’t quite understand small probabilities.

You often see in the papers things saying events we just saw should happen every ten thousand years, hundred thousand years, ten billion years. Some faculty here in this university had an event and said that a 10-sigma event should happen every, I don’t know how many billion years.

So the fundamental problem of small probabilities is that rare events don’t show in samples, because they are rare. So when someone makes a statement that this in the financial markets should happen every ten thousand years, visibly they are not making a statement based on empirical evidence, or computation of the odds, but based on what? On some model, some theory.

So, the lower the probability, the more theory you need to be able to compute it. Typically it’s something called extrapolation, based on regular events and you extend something to what you call the tails. (…)

The smaller the probability, the less you observe it in a sample, therefore your error rate in computing it is going to be very high. Actually, your relative error rate can be infinite, because you’re computing a very, very small probability, so your error rate is monstrous and probably very, very small. (…)

There are two kinds of decisions you make in life, decisions that depend on small probabilities, and decisions that do not depend on small probabilities. For example, if I’m doing an experiment that is true-false, I don’t really care about that pi-lambda effect, in other words, if it’s very false or false, it doesn’t make a difference. (…) But if I’m studying epidemics, then the random variable how many people are affected becomes open-ended with consequences so therefore it depends on fat tails. So I have two kinds of decisions. One simple, true-false, and one more complicated, like the ones we have in economics, financial decision-making, a lot of things, I call them M1, M1+.

{ Nassim Nicholas Taleb/Edge | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, mathematics | June 28th, 2011 1:39 pm

At some point, the Mongol military leader Kublai Khan (1215–1294) realized that his empire had grown so vast that he would never be able to see what it contained. To remedy this, he commissioned emissaries to travel to the empire’s distant reaches and convey back news of what he owned. Since his messengers returned with information from different distances and traveled at different rates (depending on weather, conflicts, and their fitness), the messages arrived at different times. Although no historians have addressed this issue, I imagine that the Great Khan was constantly forced to solve the same problem a human brain has to solve: what events in the empire occurred in which order?

Your brain, after all, is encased in darkness and silence in the vault of the skull. Its only contact with the outside world is via the electrical signals exiting and entering along the super-highways of nerve bundles. Because different types of sensory information (hearing, seeing, touch, and so on) are processed at different speeds by different neural architectures, your brain faces an enormous challenge: what is the best story that can be constructed about the outside world?

The days of thinking of time as a river—evenly flowing, always advancing—are over. Time perception, just like vision, is a construction of the brain and is shockingly easy to manipulate experimentally. We all know about optical illusions, in which things appear different from how they really are; less well known is the world of temporal illusions. When you begin to look for temporal illusions, they appear everywhere.

{ David M. Eagleman/Edge | Continue reading }

photos { Henri Cartier-Bresson | Ruben Natal-San Miguel }

archives, brain, halves-pairs, photogs, time | June 27th, 2011 1:54 pm

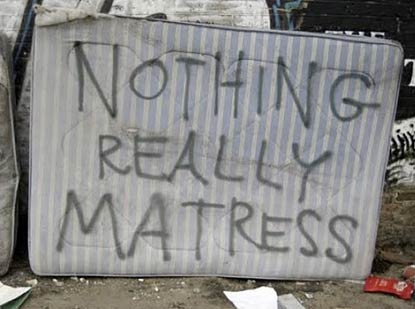

‘Your own life while it’s happening to you never has any atmosphere until it’s a memory.’ –Warhol. I like that.

Wish I was back in school so I could do a thesis on how things like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter etc are technology’s attempt to ’solve’ this problem, effectively making us nostalgic for the present as we advertise it, not live it.

{ Colleen Nika }

photo { Becky Ninkovic }

ideas, technology | June 27th, 2011 1:50 pm

halves-pairs, ideas, technology | June 24th, 2011 2:22 pm

Sleeping Beauty goes into an isolated room on Sunday and falls asleep. Monday she awakes, and then sleeps again Monday night. A fair coin is tossed, and if it comes up heads then Monday night Beauty is drugged so that she doesn’t wake again until Wednesday. If the coin comes up tails, then Monday night she is drugged so that she forgets everything that happened Monday – she wakes Tuesday and then sleeps again Tuesday night. When Beauty awakes in the room, she only knows it is either heads and Monday, tails and Monday, or tails and Tuesday. Heads and Tuesday is excluded by assumption. The key question: what probability should Beauty assign to heads when she awakes?

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

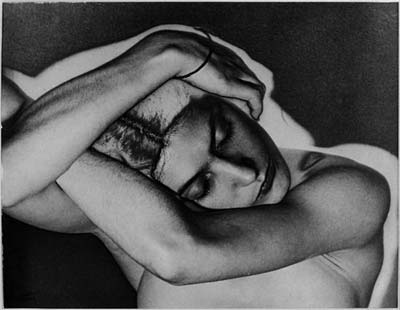

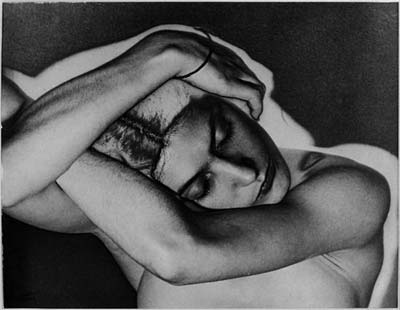

photo { Man Ray, Solarization, 1929 }

ideas, leisure, mathematics | June 24th, 2011 2:22 pm