Go back like cold ovens and ice boxes

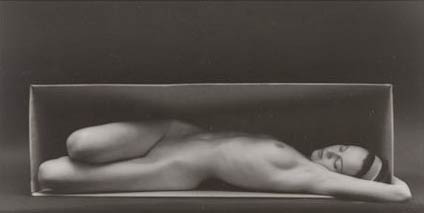

Anyone who has been trained as a physician – or is close to someone who has been – is aware that the dissection of a cadaver is an integral part of the physician’s learning and socialization. The first incision is something few physicians forget. That procedure is reproduced time after time, in country after country, and provides a seminal building block of medical education. (…) Dissecting a cadaver also gives young doctors “an appreciation for the wonders of the human body”. Students often give their first “patient” affectionate names; however, much less attention is paid to where the cadaver came from.

Supplying human cadavers is left to the responsibility of others, most notably the anatomy course instructors or school administrators. These individuals are not alone in trying to secure specimens. Alongside primary medical education providers, a large number and wide range of other users are also trying to secure cadavers for their own needs. The continuing training of medical doctors, for instance, relies on cadavers. In addition, allied health professionals, emergency medical workers, and medical researchers all demand cadavers or cadaver parts. As an illustration, orthopedic surgeons use human joints to fine-tune their skills to learn new procedures. Similarly, some researchers studying Alzheimer’s disease might require human brains. Also, government agencies and automotive manufacturers that try to improve automotive safety benefit from research using cadavers.

It does not help that many users seek the same “good” type of cadavers. A good specimen, in this context, means a young cadaver, one not overly obese or too evidently diseased. Such a description is generally the antithesis of cadavers made typically available through donations, so the supply is further strained. Not surprisingly, both in the United States and other countries, those who require cadavers often question the adequacy of the supply and regularly voice their fear of shortages of cadavers.

However, trying to address the question of a shortage of cadavers often means facing the taboo on trading human anatomical goods. Blood, organs, and cadavers are generally thought to be better left untouched by market dynamics. (…) In essence, many would argue that blood, organs, and cadavers should not be considered goods.

That said, the demand for cadavers remains strong, and numerous ideas have been voiced to augment the supply. As an illustration, there is an ongoing debate about the impact of using financial incentives for donors or their families to encourage anatomical donations. Similarly, surveys of potential whole-body donors seek to gain insight into the reluctance to donate and how better to educate potential donors. By understanding the reluctance to donate, the hope is that the root causes of such reluctance might be addressed.

Another novel solution to the cadaver shortage lies in securing specimens from a new set of actors in the commerce in cadavers. These actors are legal entrepreneurial ventures that have been operating for more than a decade in the United States; they cater to domestic users and international ones alike. (The procurement of cadavers is regulated, but the export of cadavers much less so.) For medical schools in countries with strong societal norms against donating one’s body to science, such a supply route can prove quite practical. In those and other instances, medical schools can purchase for a fee the entrepreneurial ventures’ services and help medical students learn their craft. Like corn, wheat, and civilian aircrafts, cadavers sent abroad can be seen as another U.S. export product, although one dwarfed by these other export categories. The notion of human cadavers as a thriving export industry is obviously far away; however, I want to suggest that its legality and limited occurrence underline crucial new developments in markets for anatomical goods. While the international organ trade is almost unanimously condemned, human cadavers can legally freely flow across the globe.

{ A Market for Human Cadavers in All but Name by Michel Anteby | Economic Sociology, November 2009 | PDF | Continue reading }