‘The better telescopes become, the more stars appear.’ –Julian Barnes

{ YouTube }

{ Our Imaging Services department is steadily building a comprehensive image archive of all works in the collection, while simultaneously managing more urgent photography requests, including those from outside the Museum. (…) Take a look at this sleek, smooth sculpture by Constantin Brancusi—a shimmering ovoid form seemingly floating in space. Would it ever strike you as one of the most difficult objects in our collection to photograph? Well, it is. | MoMA | full story }

Despite rumors to the contrary, there’s many ways in which the human brain isn’t all that fancy. Let’s compare it to the nervous system of a fruit fly. Both are made up of cells — of course — with neurons playing particularly important roles. Now one might expect that a neuron from a human will differ dramatically from one from a fly. Maybe the human’s will have especially ornate ways of communicating with other neurons, making use of unique “neurotransmitter” messengers. Maybe compared to the lowly fly neuron, human neurons are bigger, more complex, in some way can run faster and jump higher.

But no. Look at neurons from the two species under a microscope and they look the same. They have the same electrical properties, many of the same neurotransmitters, the same protein channels that allow ions to flow in and out, as well as a remarkably high number of genes in common. Neurons are the same basic building blocks in both species.

So where’s the difference? It’s numbers — humans have roughly a million neurons for each one in a fly. And out of a human’s 100 billion neurons emerge some pretty remarkable things. With enough quantity, you generate quality.

Neuroscientists understand the structural bases of some of these qualities.

{ NY Times | Continue reading | On the Human/National Humanities Center }

A German researcher has studied medieval criminal law and found that our image of the sadistic treatment of criminals in the Dark Ages is only partly true. Torture and gruesome executions were designed in part to ensure the salvation of the convicted person’s soul. (…)

New access to existing sources, such as law books and pamphlets, has enabled Schild to soften the prevailing view of the past. Many descriptions from centuries past were “distorted and exaggerated to make the past seem particularly dark and the present more radiant,” says Schild.

The Renaissance poet Petrarch, for example, carried this sort of fiction to extremes. He dreamed up the “brazen bull,” a hollow object made of metal that was placed over a fire while the condemned criminals inside were cooked alive. But the executioners of the Middle Ages were not driven by such sadistic impulses.

photo { Jocelyn Lee }

The way you dance can reveal information about your personality, scientists have found.

Using personality tests, the researchers assessed volunteeers into one of five “types”. They then observed how each members of each group danced to different kinds of music. They found that:

* Extroverts moved their bodies around most on the dance floor, often with energetic and exaggerated movements of their head and arms.

* Neurotic individuals danced with sharp, jerky movements of their hands and feet – a style that might be recognised by clubbers and wedding guests as the “shuffle”.

* Agreeable personalities tended to have smoother dancing styles, making use of the dance floor by moving side to side while swinging their hands.

* Open-minded people tended to make rhythmic up-and-down movements, and did not move around as much as most of the others.

* People who were conscientious or dutiful moved around the dance floor a lot, and also moved their hands over larger distances than other dancers.

He’s back in Iraq, on foot patrol, nervously walking down a street that suggests Basra, when it happens again—an explosion right across the street. The sidewalk shakes, he smells the acrid smoke, and as the panic starts to take over, his therapist says, “Turn right and walk up those stairs over there.” He goes up a stone stairway to the roof of a building and then watches the blast again, safely removed.

Only the client isn’t back in Iraq—he’s watching the scene unfold on a computer screen.

Therapists are making increasing use of virtual reality (VR) therapy, which, several studies suggest, increases the effectiveness of exposure therapy, the most empirically supported treatment for anxiety disorders such as PTSD and phobias.

A metanalysis in the April 2008 Journal of Anxiety Disorders found that VR is more effective than recalling memories exclusively through narrative, and just as effective as in vivo exposure for a wide range of anxiety disorders.

…an important question in philosophy, the problem of presuppositions.

An example is Descartes’ celebrated phrase at the beginning of the Discourse on the Method:

Good sense is the most evenly shared thing in the world . . the capacity to judge correctly and to distinguish the true from the false, which is properly what one calls common sense or reason, is naturally equal in all men…

For Descartes, thought has a natural orientation towards truth, just as for Plato, the intellect is naturally drawn towards reason and recollects the true nature of that which exists. This, for Deleuze, is an image of thought.

Although images of thought take the common form of an ‘Everybody knows…’, they are not essentially conscious. Rather, they operate on the level of the social and the unconscious, and function, “all the more effectively in silence.”

photo { Jeff Luker }

The concept of trust is in many ways the connective tissue of society—governing everything from our personal relationships to our common use of currency.

Most, if not all, of the decisions we make every day rely on one form or another of trust. But what if our capacity for faith is simply the result of brain chemistry?

Economic researchers are uncovering the chemical triggers in our brains that spark feelings of trust—and using their findings to better understand how markets work.

installation { Francesco Fonassi }

Does forensic evidence really matter as much as we believe? New research suggests no, arguing that we have overrated the role that it plays in the arrest and prosecution of American criminals.

A study, reviewing 400 murder cases in five jurisdictions, found that the presence of forensic evidence had very little impact on whether an arrest would be made, charges would be filed, or a conviction would be handed down in court.

A mere 13.5 percent of the murder cases reviewed actually had physical evidence that linked the suspect to the crime scene or victim. The conviction rate in those cases was only slightly higher than the rate among all other cases in the sample. And for the most part, the hard, scientific evidence celebrated by crime dramas simply did not surface. According to the research, investigators found some kind of biological evidence 38 percent of the time, latent fingerprints 28 percent of the time, and DNA in just 4.5 percent of homicides.

screenshot { Errol Morris, The Thin Blue Line, 1988 }

I was reading my feed the other day and an article called “Having oral sex increases likelihood of intercourse among teens” came up. Naturally, the first thing that came to mind was “No shit”. The second was “How could someone get paid for researching this?” (…)

This study isn’t alone in the obviousness of its results:

▪ “Spouses with identical residential addresses before marriage: an indicator of pre-marital cohabitation.“, showing that the majority of English and Welsh newly-weds live together before marriage;

▪ “Don’t want to show fellow students my naughty bits: medical students’ anxieties about peer examination of intimate body regions at six schools across UK, Australasia and Far-East Asia”, showing that first year med students don’t like their classmates formally examining their genitals and breasts.

▪ “Determinants and consequences of female attractiveness and sexiness: realistic tests with restaurant waitresses.“, showing that more attractive waitresses get more tips.

photo { Hannah Davis }

It turns out there’s some truth to the idea that people of other races “all look alike.” A new study demonstrates that people have more trouble recognizing faces of people of other races.

While this effect has been observed for almost a hundred years, scientists still don’t fully understand why it happens and who it happens to. (…)

Both the Caucasian and Asian groups had a much more difficult time recognizing identical faces from another race.

Other things came out: weekend are good, spending too much time alone is bad, illness is a major drain on your emotional well-being, and so is caring for another adult, or a child (major increases in worry and stress there). College graduates report more stress, and otherwise being a college graduation has no significant effect on your daily happy or sad events. Religion increases positive daily life events, but doesn’t decrease sadness or worry.

Smoking turned out to be a REALLY strong predictor of low emotional well-being, and came out regardless of income or education or anything else. (…)

The negative things in life seem to affect people making less than $75K a lot more than higher incomes. Things like headaches and illness are reported more frequently (but whether or not these are related to stress isn’t determined).

In addition, the pain of some life occurrences, like divorce or chronic disease, is made a LOT worse by being of lower income.

So basically, more money does NOT mean more problems, but at a certain level, less money DOES.

The famous lifelike poses of many victims at Pompeii—seated with face in hands, crawling, kneeling on a mother’s lap—are helping to lead scientists toward a new interpretation of how these ancient Romans died in the A.D. 79 eruptions of Italy’s Mount Vesuvius.

Until now it’s been widely assumed that most of the victims were asphyxiated by volcanic ash and gas. But a recent study says most died instantly of extreme heat, with many casualties shocked into a sort of instant rigor mortis.

Filing down horse teeth is a slobbery job. But Carl Mitz is grateful that he now has the undisputed legal right to do it.

This week, Mr. Mitz and three others won a three-year legal battle against the Texas Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners, which had sought to restrict the ancient craft of horse-teeth floating—an obscure job that involves filing a horse’s teeth to improve its bite—to licensed veterinarians. (…)

Texas, however, likely will continue to press the issue, meaning the victory could be fleeting. (…)

Horse-teeth floating is a lucrative job. Some practitioners say they can make $300,000 a year, and those who do it say it’s straightforward and requires no special training. But some veterinarians fear that unskilled floaters will damage the horse’s gums or strip away protective enamel.

photo { Audrey Corregan for Blend magazine, 2008 }

Everyone knows someone who likes to listen to some music while they work. Maybe it’s one of your kids, listening to the radio while they try to slog through their homework. (…)

It’s a widely held popular belief that listening to music while working can serve as a concentration aid, and if you walk into a public library or a café these days it’s hard not to notice a sea of white ear-buds and other headphones. Some find the music relaxing, others energizing, while others simply find it pleasurable. But does listening to music while working really improve focus? It seems like a counterintuitive belief – we know that the brain has inherently limited cognitive resources, including attentional capacity, and it seems natural that trying to perform two tasks simultaneously would cause decreased performance on both.

The currently existing body of research thus far has yielded contradictory results. Though the results of most empirical studies suggest that music often serves more as a distraction than a study aid, a sizable minority have displayed some instances in which music seems to have improved performance on some tasks.

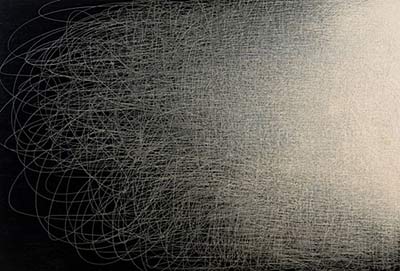

artwork { Il Lee }

What do you need to succeed in business? A mixture of luck and good judgement, according to Mikhail Fridman, one of Russia’s richest men and currently head of the Alfa Group. Gorbachev’s 1980s reforms made private enterprise possible – Fridman and others like him did the rest, as can be seen from this transcript of his lecture at the Publishers’ Forum in Lvov.

I think that to become a major, very successful entrepreneur, you really need to be in the right place at the right time – a lot of things have to coincide. It would probably be difficult to become an entrepreneur in a small or a very poor country. The world is changing and becoming globalized, and the list of the richest people naturally includes Chinese, Indians, Americans and Russians – Russia is after all an enormous country with enormous resources. But the richest person in the world is the Mexican Carlos Slim, who is certainly not from the largest and richest country in the world. Nevertheless, from his beginnings in a small town he created an enormous business empire, which works practically all over the Latin American continent and successfully competes with representatives of other economies of the world, which are much larger and stronger. So I think that everyone present here who decides to devote his life to entrepreneurship has a chance of achieving virtually unlimited success.

But the most important thing is not how to become a major entrepreneur or head of enormous business projects, but how to become an entrepreneur in general. For this I believe it’s not so much the circumstances that are important, as a completely different quality – entrepreneurial talent.

photo { Zackary Canepari }

In “What Technology Wants,” Kelly provides an engaging journey through the history of “the technium,” a term he uses to describe the “global, massively interconnected system of technology vibrating around us,” extending “beyond shiny hardware to include culture, art, social institutions and intellectual creations of all types.”

We learn, for instance, that our hunter-gatherer ancestors, despite their technological limitations, may have worked as little as three to four hours a day.

Since then, the technium has grown exponentially: while colonial American households boasted fewer than 100 objects, Kelly’s own home contains, by his reckoning, more than 10,000. As Kelly is a gadget-phile by trade, this index probably inflates the current predominance of technology and its products, but a thoroughly mundane statistic makes the same point: a typical supermarket now offers more than 48,000 different items.

Kelly argues convincingly that this expansion of technology is beneficial. Technology creates choice and therefore enhances our potential for self-realization. No longer tied to the land, we can become, in principle, what we want to become. (…)

Kelly’s exploration of the factors underlying these trends, however, is more controversial. He sees evolution — both biological and technological — as an inexorable and predictable process; if life were to begin again on Earth, he argues, we’d see not only the re-evolution of humans, but humans who would invent pretty much the same stuff. To support his claims, Kelly describes parallel inventions on different isolated continents (the blowgun and the abacus, for example), and the presence of near-simultaneous inventions in modern times (the light bulb was invented at least two dozen times).