noise and signals

A low-pitched voice in a man is associated with a litany of masculine traits: dominance, strength, greater physical size, more attractiveness to women, and so on. But new research strikes one trait off that list: virility.

An Australian study looked at male voice pitch, women’s perceptions of it, and semen quality. Their first finding was no surprise: Women like deep voices and consider them masculine.

But contrary to expectations, they also found that these men aren’t better off in the semen department. In fact, by one measure of sperm quality — sperm concentration in ejaculate — men with the attractive voices appeared to have a disadvantage.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

related { Breakthrough in male fertility: scientist grow sperm in laboratory }

noise and signals, relationships, science, sex-oriented | January 4th, 2012 6:26 pm

Two scientists who study icky sounds have figured out why fingernails dragged across a chalkboard make people’s skin crawl. It’s not the highest or lowest sounds in the squeak that are so annoying, but rather tones that lie in the range of a piano keyboard.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

photo { Jordan Kinsler }

noise and signals, science | November 4th, 2011 11:40 am

Dolphins are known to make three types of sounds: whistles, clicks and burst pulses. Whistles are thought to be identification sounds, like names, while clicks are used to navigate and to find prey with echolocation.

Burst pulses, which can sound like quarreling cartoon chipmunks, are a muddy mixture of the two, and Dr. Herzing believes that much information may be encoded in these sounds, as well as in dolphins’ ultra-high frequencies, which humans cannot hear.

The two-way system she will test next year is being developed with artificial intelligence scientists at Georgia Tech. It consists of a wearable underwater computer that can make dolphin sounds, but also record and differentiate them in real time. It must also distinguish which dolphin is making the sound, a common challenge since dolphins rarely open their mouths.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

dolphins, noise and signals, science | September 22nd, 2011 8:33 pm

In a series of two experiments, Smith and colleagues show that memory in women is sensitive to male voice pitch, a cue important for mate choice because it can indicate genetic quality as well as signal behavioral traits undesirable in a long-term partner. (…)

The authors found that women had a strong preference for the low pitch male voice and remembered objects more accurately when they have been introduced by the deep male voice.

{ Springer | Continue reading }

noise and signals, science | September 13th, 2011 3:53 pm

{ SETI@Home is a distributed computing initiative that analyses radio signals for signs of extra terrestrial intelligence. SETI@Home volunteers have identified some 4.2 billion signals. Most, if not all, of them are likely to be the result of noise or interference. | The Physics arXiv Blog }

noise and signals, space | September 13th, 2011 3:20 pm

Whines, cries, and motherese have important features in common: they are all well-suited for getting the attention of listeners, and they share salient acoustic characteristics – those of increased pitch, varied pitch contours, and slowed production, though the production speed of cries varies. Motherese is the child-directed speech parents use towards infants and young children to sooth, attract attention, encourage particular behaviors, and prohibit the child from dangerous acts. Infant cries are the sole means of communication for infants for the first few months, and a primary means in the later months. Cries signal that the infant needs care, be it feeding, changing, protection, or physical contact. Whines enter into a child’s vocal repertoire with the onset of language, typically peaking between 2.5 and 4 years of age. This sound is perceived as more annoying even than infant cries.

These three attachment vocalizations – whines, cries, and motherese – each have a particular effect on the listener; to bring the attachment partner nearer. (…)

Participants, regardless of gender or parental status, were more distracted by whines than machine noise or motherese as measured by proportion scores. In absolute numbers, participants were most distracted by whines, followed by infant cries and motherese.

{ Whines, cries, and motherese: Their relative power to distract | Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology | Continue reading }

photo { Tod Seelie }

kids, noise and signals, relationships, science | July 6th, 2011 6:44 pm

If a tree falls in the forest, and there’s nobody around to hear, does it make a sound?

Of course, the answer depends on how we choose to interpret the use of the word ‘sound’. (…)

Here the word ‘sound’ is used to describe a physical phenomenon –- the wave disturbance. But sound is also a human experience, the result of physical signals delivered by human sense organs which are synthesized in the mind as a form of perception.

Now, to a large extent, we can interpret the actions of human sense organs in much the same way we interpret mechanical measuring devices. The human auditory apparatus simply translates one set of physical phenomena into another, leading eventually to stimulation of those parts of the brain cortex responsible for the perception of sound. It is here that the distinction comes. Everything to this point is explicable in terms of physics and chemistry, but the process by which we turn electrical signals in the brain into human perception and experience in the mind remains, at present, unfathomable.

Philosophers have long argued that sound, colour, taste, smell and touch are all secondary qualities which exist only in our minds. We have no basis for our common-sense assumption that these secondary qualities reflect or represent reality as it really is. So, if we interpret the word ‘sound’ to mean a human experience rather than a physical phenomenon, then when there is nobody around there is a sense in which the falling tree makes no sound at all.

This business about the distinction between ‘things-in-themselves’ and ‘things-as-they-appear’ has troubled philosophers for as long as the subject has existed, but what does it have to do with modern physics, specifically the story of quantum theory? In fact, such questions have dogged the theory almost from the moment of its inception in the 1920s.

{ OUP | Continue reading }

photo { Walter Pickering }

ideas, noise and signals, science | June 24th, 2011 2:21 pm

Designers and engineers labour to create artificial noises that make life easier whether by generating atmosphere or making you feel more secure. (…)

To produce the ideal clunk, car doors are designed to minimise the amount of high frequencies produced (we associate them with fragility and weakness) and emphasise low, bass-heavy frequencies that suggest solidity. The effect is achieved in a range of different ways – car companies have piled up hundreds of patents on the subject – but usually involves some form of dampener fitted in the door cavity. Locking mechanisms are also tailored to produce the right sort of click and the way seals make contact is precisely controlled. (…)

The EU is still in the process of drafting a law which will require electric vehicle makers to have a signature sound with a minimum volume to make sure other road users can hear the otherwise silent machines whizzing towards them. (…)

While some US sports teams use artificial crowd noise to unsettle the opposition, lots of venues use it as a handy way to help amp up the atmosphere and encourage the real spectators to join in. (…)

Lots of modern telephone systems as well as software like Skype employ noise reduction techniques. Unfortunately, that can result in total silence at quiet points in a conversation and leave you wondering if the call has stopped entirely. To fill those lulls, the software adds artificial noise at a barely audible volume.

{ Humans Invent | Continue reading }

noise and signals, technology, transportation | June 22nd, 2011 4:20 pm

In the first years of the twenty-first century, New York City police officers had six different siren noises at their fingertips to alternate and overdub as they attempted to bore through stagnant traffic. The “Yelp” is a high-pitched, rapidly oscillating, jumpy sound that suggests a small dog with large teeth has hold of your thigh and is not about to let go. The “Wail” is the classic keening noise that the Furies might release while pursuing vengeance. The “Hi-Lo,” or “European,” is whiney, forlorn—prone to depression, but undeniably civilized. The “Air-Horn” is vulgarity incarnate—a burp, a rasp, an all-out bursty blast. The “Fast” or “Priority” resembles a hysteric who’s just mainlined crystal meth. The “Manual” is an outcast loner raising its rifle in a solitary low-to-high pulse.

The summer of 2007 saw the first broaching of the possibility that a seventh instrument might be added to the ensemble.

The Rumbler™.

{ Cabinet | Continue reading | NY Times | N.Y.P.D. Sirens | audio }

new york, noise and signals | June 3rd, 2011 2:00 pm

Can the lost art of whistling make a comeback?

“No great or successful man ever whistles,” said New York University philosophy professor Charles Gray Shaw in 1931. “Whistling is an unmistakable sign of the moron. It’s only the inferior and maladjusted individual who ever seeks emotional relief in such a bird-like act as that of whistling,” he concluded.

Today, Shaw’s words probably wouldn’t elicit a response, but in those days whistling was viewed in a decidedly positive light. In the 1920s and ’30s, whistlers were accepted as professional artists, traveling with Big Bands and becoming household names in their own right. There were even schools—a total of nine, scattered around the U.S.—where one could go to study whistling, including Agnes Woodward’s Los Angeles School of Artistic Whistling.

Ordinary people enjoyed whistling—while walking down the street, doing chores, and of course, while they worked. (…) But it’s been at least a half-century since whistling was prominent in popular culture, and people who whistle in public today are likely to be greeted with looks of disapproval.

{ Failure | Continue reading }

flashback, noise and signals | February 14th, 2011 6:00 pm

First we must ask Why does a woman (or a man, for the matter) vocalize during sex at all? Sure, there might be a host of valid social reasons - one might be to boost the ego of the man [92% of the women in study agreed to this statement, and 87% reported vocalizing for this very purpose] (Brewer and Hendrie, 2010), or to deceive the man that they are a competent lover (68% of women reported wanting to stay with a man even though he never helped her climax) (Brewer and Hendrie, 2010).

But from an evolutionary perspective we must be mindful of a few things: First, men do not vocalize in the same manner as women. Second, comparative evidence in chimps suggests that vocalizations are for attracting more males to a sexual encounter (in order to have more sex), which is further supported by the fact that when chimps are engaging in down-strata copulation (that is, if the women is having sex with someone she ’shouldn’t’ be having sex with) she still makes chimpanzee sex-faces, but fails to make the vocalizations.

{ Psycasm | Continue reading }

painting { Erik Mark Sandberg }

noise and signals, relationships, science, sex-oriented | February 14th, 2011 4:08 pm

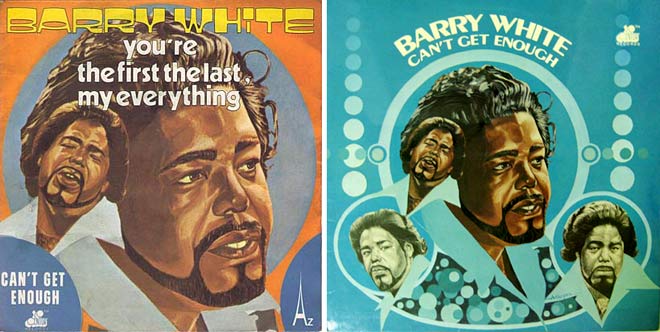

music, noise and signals | January 28th, 2011 2:18 pm

flashback, music, noise and signals | October 27th, 2010 7:42 pm

The taste of Kit Kat candy bars, Coca-Cola beverages and Jelly Belly candies are known to stimulate cravings and subsequently influence consumers’ spending habits, but now researchers suggest simply hearing the sound of those brands and others with repetitively structured names can induce similar outcomes.

Across several product categories, audible exposure to repetitive-sounding brand names favorably affects how consumers perceive and choose items and decide where to buy them, reveals a study recently published in the Journal of Marketing.

Researchers said their findings provide the first evidence of this discovery, which could prove beneficial for marketers, advertisers and store managers.

“Companies have spent millions of dollars choosing their brands and their brand names and they’ve been picked explicitly to have an influence on consumers,” wrote University of Alberta marketing professor Jennifer Argo. “We show that it can get you at the affective level.”

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

related { The Coke Machine—part nonfiction narrative, part history of the Coca-Cola Company and the many crimes it has been accused of—works hard to provide answers. | The Atlantic | full story }

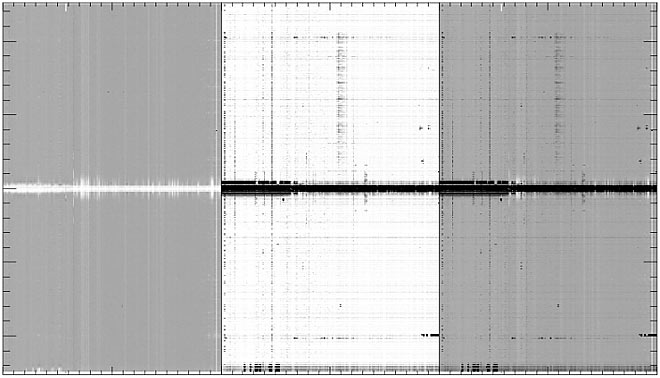

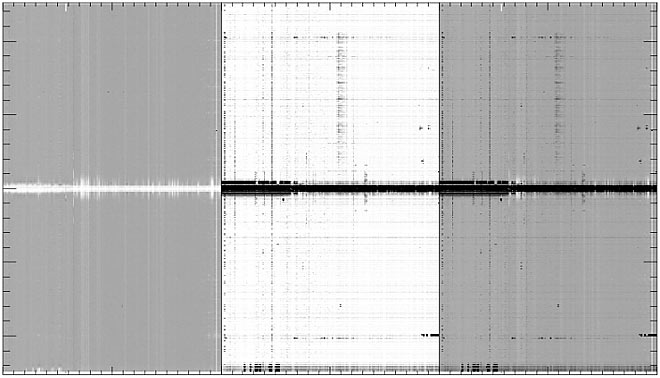

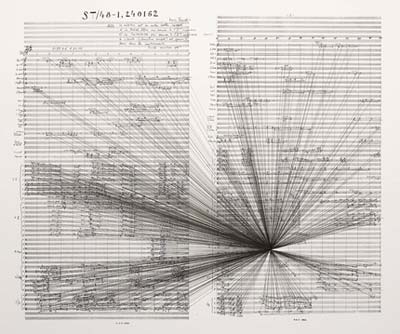

image { Marco Fusinato, Mass Black Implosion, 2007 | ink on archival facsimile of score }

economics, marketing, noise and signals, science | October 19th, 2010 12:08 pm

One of the extraordinary features of the mammalian sound detection system is the range over which it works. This extends from 11 KHz in birds to 200 KHz in marine mammals.

This is only possible because the inner ear amplifies sounds by a factor of up to 4000. That’s a huge amount of gain. So much, in fact, that it’s hard to square with conventional thinking about mechanical amplification. So there is much head scratching among biologists over how the ear achieves this amplification.

Part of the puzzle is that the amplification is not entirely passive. The inner ear is essentially a fluid-filled tube, divided along its length by a thin elastic membrane. This membrane is covered in hair cells, which come in two types.

The so-called inner hair cells convert pressure waves within the fluid into electrical signals the brain can interpret. However, the outer hair cells act like mechanical amplifiers. When struck by a pressure wave, the cells themselves begin to vibrate at the same frequency, thereby boosting the wave as it passes.

The trouble is that measurements using outer hair cells indicate that they amplify pressure waves by a factor of about 10, a gain that falls far short of what’s required.

Today, however, Tobias Reichenbach and James Hudspeth at The Rockefeller University in New York city say they’ve worked out what else is going on to boost the signal.

Sound enters the inner ear as a pressure wave which travels through the fluid filled chamber, causing the membrane that divides it along its length to vibrate, like a sheet of rubber. Since the hair cells sit on this membrane they also move.

Reichenbach and Hudspeth calculate that the vibration of the outer hair cells not only amplifies the pressure wave, but also increases the displacement of the membrane, like a child bouncing on a trampoline.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

noise and signals, science | September 20th, 2010 10:40 am

music, noise and signals | June 14th, 2010 11:07 am

I bought a Stereo! Wow! With two speakers!

But then I heard the quad with the four speakers and I was like this is it, so I got rid of the stereo and got the quad.

I’m listening to this thing and I’m like “Hey this sounds like SHIT!”

So, I got rid of that and got the dodecaphonic with the 12 speakers.

This was more to my liking…for a while.

But the ear gets pretty sophisticated pretty fast and I got rid of that and got the milliphonic with the 1,000 speakers.

And I’m listening to that one and I’m like, “Hey, this sounds like SHIT too! The other one was SHIT one, this one is SHIT too!”

So, I traded that in and got the googlephonic, which is the highest number of speakers you can have before infinity.

Sounds like SHIT!

So, then I said, “Hey, maybe it’s the needle!”

I had the typical diamond needle. I searched around got the moonrock needle, cost me 3 million bucks, but what the hey. So, now I have a googlephonic stereo with a moonrock needle.

It’s okay for a car stereo, I wouldn’t want it in my house.

{ Steve Martin }

logotype { House Industries }

archives, haha, music, noise and signals | April 28th, 2010 11:20 am

Although humans usually prefer mates that resemble themselves, mating preferences can vary with context. Stress has been shown to alter mating preferences in animals, but the effects of stress on human mating preferences are unknown. Here, we investigated whether stress alters men’s preference for self-resembling mates. (…) Our findings show that stress affects human mating preferences: unstressed individuals showed the expected preference for similar mates, but stressed individuals seem to prefer dissimilar mates.

{ Proceedings B of the Royal Society | Continue reading }

music, noise and signals, video, visual design | April 15th, 2010 7:16 am

How loud does something have to be to kill someone? I heard once on BattleBots that it took 150 decibels to stop the human heart. Is this true? If so, I’m afraid, since I work in a VERY loud job environment (I assemble 747 engines). So is there a fatal decibel level? And if so, is it really 150 decibels? Please tell me. I’m scared.

A 150-decibel noise isn’t loud enough to kill you, and even if it were, the immediate cause of death in most cases wouldn’t be direct trauma to the heart. But the TV show was right in the big-picture sense: if a noise were loud enough, you’d die.

What we’re talking about here is high-energy-impulse noise, also known as blast overpressure or air blast, which is “the sharp instantaneous rise in ambient atmospheric pressure resulting from explosive detonation or firing of weapons” (N.M. Elsayed, “Toxicology of Blast Overpressure,” Toxicology, 1997). What, you say this isn’t noise in the usual sense? Nonsense. It’s no different from a thunderclap or a sonic boom. It’s true you might not hear a truly titanic air blast, but that’s because your eardrums would shatter, and worst case you’d be dead.

{ The Straight Dope | Continue reading }

photo { Esther Mathis }

quote { Aldous Huxley! }

incidents, noise and signals | March 11th, 2010 4:49 pm

In recent years Britain has become the Willy Wonka of social control, churning out increasingly creepy, bizarre, and fantastic methods for policing the populace. But our weaponization of classical music—where Mozart, Beethoven, and other greats have been turned into tools of state repression—marks a new low.

We’re already the kings of CCTV. An estimated 20 per cent of the world’s CCTV cameras are in the UK, a remarkable achievement for an island that occupies only 0.2 per cent of the world’s inhabitable landmass.

A few years ago some local authorities introduced the Mosquito, a gadget that emits a noise that sounds like a faint buzz to people over the age of 20 but which is so high-pitched, so piercing, and so unbearable to the delicate ear drums of anyone under 20 that they cannot remain in earshot. It’s designed to drive away unruly youth from public spaces, yet is so brutally indiscriminate that it also drives away good kids, terrifies toddlers, and wakes sleeping babes.

Police in the West of England recently started using super-bright halogen lights to temporarily blind misbehaving youngsters. From helicopters, the cops beam the spotlights at youths drinking or loitering in parks, in the hope that they will become so bamboozled that (when they recover their eyesight) they will stagger home. (…)

In January it was revealed that West Park School, in Derby in the midlands of England, was “subjecting” (its words) badly behaved children to Mozart and others. In “special detentions,” the children are forced to endure two hours of classical music both as a relaxant (the headmaster claims it calms them down) and as a deterrent against future bad behavior.

{ Reason | Continue reading }

artwork { Stuart Patterson }

music, noise and signals, pipeline, technology, uh oh | March 4th, 2010 6:15 pm