science

The illusion people have that a life different from theirs would be much better

We put a lot of energy into improving our memory, intelligence, and attention. There are even drugs that make us sharper, such as Ritalin and caffeine. But maybe smarter isn’t really all that better. A new paper published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, warns that there are limits on how smart humans can get, and any increases in thinking ability are likely to come with problems. (…)

Drugs like Ritalin and amphetamines help people pay better attention. But they often only help people with lower baseline abilities; people who don’t have trouble paying attention in the first place can actually perform worse when they take attention-enhancing drugs. That suggests there is some kind of upper limit to how much people can or should pay attention. (…)

It may seem like a good thing to have a better memory, but people with excessively vivid memories have a difficult life. “Memory is a double-edged sword,” Hills says. In post-traumatic stress disorder, for example, a person can’t stop remembering some awful episode. “If something bad happens, you want to be able to forget it, to move on.”

Even increasing general intelligence can cause problems. Hills and Hertwig cite a study of Ashkenazi Jews, who have an average IQ much higher than the general European population. This is apparently because of evolutionary selection for intelligence in the last 2,000 years. But, at the same time, Ashkenazi Jews have been plagued by inherited diseases like Tay-Sachs disease that affect the nervous system. It may be that the increase in brain power has caused an increase in disease.

related { Are You Smart Enough to Know You’re Stupid? }

With a bumrush in a hull of a wherry, the twin turbane dhow

Many simple mistakes are obvious once you see them — and almost impossible to detect before you do.

Writing in The New York Times recently, Joseph Hallinan noted our tendency to infer what we see rather than actually look closely. (…) One of his best examples is a wrong note in the score of a Brahms sonata that countless musicians never noticed because, for years, they silently “corrected” it in performance. A naïve piano student kept getting it “wrong” until he looked and saw that she was actually playing what was on the page.

It’s the same problem all of us run up against when we try to proof-read a text, especially if we were the ones who wrote it. We see what we know the text means, rather than what is actually printed on the page.

artwork { John J. O’Connor }

Rain on the humming wire

One of the most notable examples of an assemblage of highly mutilated human remains from the Southwest being attributed to witchcraft execution rather than cannibalism, is Ram Mesa, southwest of Chaco Canyon near Gallup, New Mexico. This site was excavated by the University of New Mexico as a salvage project, and the relevant assemblage was reported by Marsha Ogilvie and Charles Hilton in 2000.

The Ram Mesa assemblage, consisting of 13 individuals, is pretty similar to many other assemblages in the Southwest attributed to cannibalism, but Ogilvie and Hilton make a plausible case that while the remains are clearly highly “processed” there isn’t a whole lot tying this dismemberment and mutilation to actual consumption of the remains. Few of the bones showed any evidence of burning, a condition which applies to several other cases of alleged cannibalism as well. The few cut marks, which were mostly found on children’s skulls and lower jaws, weren’t particularly indicative of the removal of large muscles that might be expected if consumption were the object.

photo { Zhe Chen }

One still hears that pebble crusted laughta, japijap cheerycherrily, among the roadside tree

According to research funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, nearly 25 percent of older adults had small pockets of dead brain cells that may have been caused by unnoticed “silent strokes.” (…)

Another study also published by the journal Neurology this week suggested that certain vitamins and a low-trans-fat diet may help preserve memory loss.

The researchers found that trans fat (found in fried and many processed foods) contributed to “more shrinkage of the brain” in addition to less cognitive recognition.

To the window! To the wall! Till the sweat drips from my balls! Skeet, skeet, skeet, skeet!

Even though chili fruits are popular amongst humans for being hot, they didn’t evolve this character to keep foodies and so-called “chili-heads” happy. Previous research indicates that chilis, Capsicum spp., evolved their characteristic “heat” or pungency as a chemical defence to protect their fruits from fungal infections and from being eaten by herbivores. Chili pungency is created by capsaicinoids, a group of molecules that are produced by the plant and sequestered in its fruits. Capsaicinoids trigger that familiar burning sensation by interacting with a receptor located in pain- and heat-sensing neurons in mammals (including humans).

In contrast, birds lack this specific receptor protein, so their pain- and heat-sensing neurons remain undisturbed by capsaicinoids, which is the reason they eat chili fruits with impunity. Additionally, because birds lack teeth, they don’t damage chili seeds, which pass unharmed through their digestive tracts. For these reasons, wild chili fruits are bright red, a colour that attracts birds, so the plants effectively employ birds to disperse their seeds far and wide.

What do you want, a cookie?

One particular process in communication is to send and receive wordless messages. This kind of information transmission is commonly referred to as “nonverbal communication” (NVC). Nonverbal signals include facial expressions, bodily orientation, movements, posture, vocal cues (other than words), eye gaze, physical appearance, interpersonal spacing, and touching. As such, they support and moderate speech, facilitate the expression of emotions, help communicating people’s attitudes, convey information about personality, and thus negotiate interpersonal relationships, even in the form of rituals. (…) There seems to be some kernel of truth in the proverb that “actions speak louder than words.” (…)

Some support on the significance of NVC in social life comes from studies that have investigated non-verbal cues in human courtship situations. In these studies, first encounters of opposite-sex strangers were covertly filmed in “unstaged interaction” to investigate flirting behavior. When opposite sex strangers meet for the first time, they both face the risk of being deceived. Neither opponent is aware of the other’s intention, thus both have to rely heavily on non-verbal cues. Grammer (1990) reported that, in such a situation, there is a remarkable consistency in the repertoire of female solicitation behaviors in the presence of a male stranger, including eye- contact, followed by looking away, special postures, ways of walking, and so on. Interestingly, men were found to approach women who expressed high rates of signaling these behaviors more frequently.

In later study, Grammer et al. (1999) found that some information about female interest is not only inherent in the number of certain non-verbal signals, but is also encoded in the quality of body movements, such as their amplitude and speed. For example, women moved more frequently, but also displayed smaller and slower movements when they were interested in a man. Men in turn reacted to the quality of these movements positively and judged the situation to be more pleasant.

Do you think I care whether you agree with me? No. I’m telling you why I disagree with you. That, I do care about.

Measuring power and influence on the web is a matter of huge interest. Indeed, algorithms that distill rankings from the pattern of links between webpages have made huge fortunes for companies such as Google. One the most famous of these is the Hyper Induced Topic Search or HITS algorithm which hypothesises that important pages fall into two categories–hubs and authorities–and are deemed important if they point to other important pages and if other important pages point to them. This kind of thinking led directly to Google’s search algorithm PageRank. The father of this idea is John Kleinberg, a computer scientist now at Cornell University in Ithaca, who has achieved a kind of cult status through this and other work. It’s fair to say that Kleinberg’s work has shaped the foundations of the online world.

Today, Kleinberg and a few pals put forward an entirely different way of measuring power and influence; one that may one day have equally far-reaching consequences.

These guys have worked out how to measure power differences between individuals using the patterns of words they speak or write. In other words, they say the style of language during a conversation reveals the pecking order of the people talking.

“We show that in group discussions, power differentials between participants are subtly revealed by how much one individual immediately echoes the linguistic style of the person they are responding to,” say Kleinberg and co.

The key to this is an idea called linguistic co-ordination, in which speakers naturally copy the style of their interlocutors. Human behaviour experts have long studied the way individuals can copy the body language or tone of voice of their peers, some have even studied how this effect reveals the power differences between members of the group.

Now Kleinberg and so say the same thing happens with language style. They focus on the way that interlocutors copy each other’s use of certain types of words in sentences. In particular, they look at functional words that provide a grammatical framework for sentences but lack much meaning in themselves (the bold words in this sentence, for example). Functional words fall into categories such as articles, auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, high-frequency adverbs and so on.

The question that Kleinberg and co ask is this: given that one person uses a certain type of functional word in a sentence, what is the chance that the responder also uses it?

To find the answer they’ve analysed two types of text in which the speakers or writers have specific goals in mind: transcripts of oral arguments in the US Supreme Court and editorial discussions between Wikipedia editors (a key bound in this work is that the conversations cannot be idle chatter; something must be at stake in the discussion).

Wikipedia editors are divided between those who are administrators, and so have greater access to online articles, and non-administrators who do not have such access. Clearly, the admins have more power than the non-admins.

By looking at the changes in linguistic style that occur when people make the transition from non-admin to admin roles, Kleinberg and co cleverly show that the pattern of linguistic co-ordination changes too. Admins become less likely to co-ordinate with others. At the same time, lower ranking individuals become more likely to co-ordinate with admins.

A similar effect also occurs in the Supreme Court (where power differences are more obvious in any case).

Curiously, people seem entirely unware that they are doing this. “If you are communicating with someone who uses a lot of articles — or prepositions, orpersonal pronouns — then you will tend to increase your usage of these types of words as well, even if you don’t consciously realize it,” say Kleinberg and co.

photo { Robert Whitman, F***ed Up In Minneapolis | Black & White Gallery, Brooklyn, NY, until Jan 14 }

Then near the approach towards the summit of its climax, with ambitious interval band selections

According to the research, in modern America the average income required to be happy day-to-day, to experience “emotional well being” is about $75,000 a year. According to the researchers, past that point adding more to your income “does nothing for happiness, enjoyment, sadness, or stress.” A person who makes, on average, $250,000 a year has no greater emotional well-being, no extra day-to-day happiness, than a person making $75,000 a year. In Mississippi it is a bit less, in Chicago a bit more, but the point is there is evidence for the existence of a financiohappiness ceiling. The super-wealthy may believe they are happier, and you may agree, but you both share a delusion.

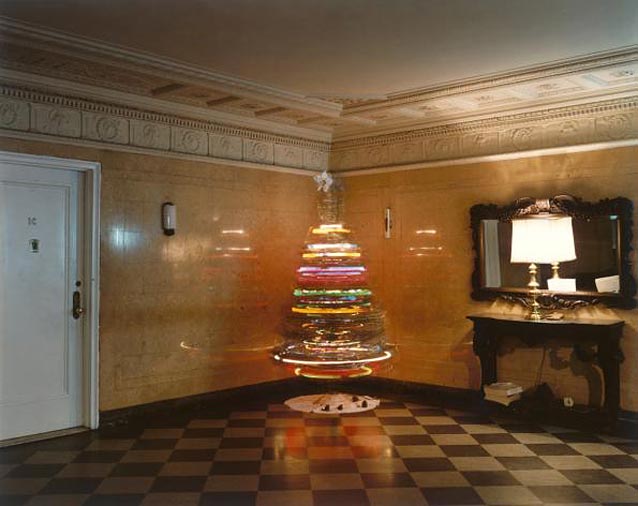

photo { Joel Meyerowitz, Spinning Christmas Tree, New York City, 1977 }

Sorry angel, sorry soon

“I’m sorry” is infamous for its inadequacy. It often seems flippant, insincere, or incomplete, as in “I’m sorry you feel that way” or “I’m sorry, but…” (…)

Researchers found evidence to support the widely-held assumption that women apologize more frequently than men. They also found, however, that women reported committing more offenses than men, and this difference fully accounted for the apology finding. In other words, men apologized for the same proportion of the offenses that they believed they had committed — they just didn’t report committing as many offenses.

related { Why Some People Say ‘Sorry’ Before Others }

‘So you gotta look at OJ’s situation. He’s paying $25,000 a month in alimony, got another man driving around in his car and fucking his wife in a house he’s still paying the mortgage on. Now I’m not saying he should have killed her… but I understand.’ –Chris Rock

The exchange of gifts at a wedding is customary in cultures all around the world. To my knowledge, however, there are no cultures in which bride and groom traditionally trade poisonous presents. (…)

If we were worried the bride might be brutally devoured on her way to the reception (by her new in-laws, perhaps), a gift of this kind might be precisely what she needs to stay alive.

An unlikely dilemma? For humans, perhaps so — but not for insects. And there are indeed certain species of insects whose mating rituals feature precisely this kind of gift, generally one given by the groom to the bride. His intentions in so doing are strictly honorable, of course, for females who receive such presents are better-equipped to deter predators.

It’s easy to be famous. It’s hard to have fans.

At thirty-eight, Kiehl is one of the world’s leading younger investigators in psychopathy, the condition of moral emptiness that affects between fifteen to twenty-five per cent of the North American prison population, and is believed by some psychologists to exist in one per cent of the general adult male population. (Female psychopaths are thought to be much rarer.) Psychopaths don’t exhibit the manias, hysterias, and neuroses that are present in other types of mental illness. Their main defect, what psychologists call “severe emotional detachment”—a total lack of empathy and remorse—is concealed, and harder to describe than the symptoms of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. This absence of easily readable signs has led to debate among mental-health practitioners about what qualifies as psychopathy and how to diagnose it. (…)

In January of 2007, Kiehl arranged to have a portable functional magnetic-resonance-imaging scanner brought into Western—the first fMRI ever installed in a prison. So far, he has recruited hundreds of volunteers from among the inmates. The data from these scans, Kiehl hopes, will confirm his theory, published in Psychiatry Research, in 2006, that psychopathy is caused by a defect in what he calls “the paralimbic system,” a network of brain regions, stretching from the orbital frontal cortex to the posterior cingulate cortex, that are involved in processing emotion, inhibition, and attentional control. (…)

The inmate was being shown a series of words and phrases, and was supposed to rate each as morally offensive or not. There were three kinds of phrases: some were intended as obvious moral violations, like “having sex with your mother”; some were ambiguous, like “abortion”; and some were morally neutral, like “listening to others.” The computer software captured not only the inmate’s response but also the speed with which he made his judgment. The imaging technology recorded which part of the brain was involved in making the decision and how active the neurons there were. (…)

Neurons in the brain consume oxygen when they are “firing,” and the oxygen is replenished by iron-laden hemoglobin cells in the blood. The scanner’s magnet temporarily aligns these iron molecules in the hemoglobin cells, while the imaging technology captures a rapid series of “slices”—tiny cross-sections of the brain. The magnet is superconductive, which means it operates at very cold temperatures (minus two hundred and sixty-nine degrees Celsius). The machine has a helium cooling system, but if the system fails the magnet will “quench.” Quenches are an MRI technician’s worst fear; a new magnet costs about two million dollars.

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading | Read more: The Disconnection of Psychopaths }

We in the nuclear seasons, in the shelter I survived this road

The ability to trust, love, and resolve conflict with loved ones starts in childhood—way earlier than you may think. That is one message of a new review of the literature in Current Directions in Psychological Science.

“Your interpersonal experiences with your mother during the first 12 to 18 months of life predict your behavior in romantic relationships 20 years later,” says psychologist Jeffry A. Simpson, the author, with University of Minnesota colleagues W. Andrew Collins and Jessica E. Salvatore. “Before you can remember, before you have language to describe it, and in ways you aren’t aware of, implicit attitudes get encoded into the mind,” about how you’ll be treated or how worthy you are of love and affection.

While those attitudes can change with new relationships, introspection, and therapy, in times of stress old patterns often reassert themselves.

You reach an age when you read the same few books over and over

Hot guys tend to underestimate women’s interest in them, while other men, particularly those looking for a one-night stand, are more likely to think a woman is much more into them than she actually is, a new study says.

Women, however, showed the opposite bias — they routinely underestimated men’s interest in them.

This sort of self-deception may help both men and women play the mating game successfully, suggest the researchers, a team of psychologists from the University of Texas, Austin. The findings also fits with past research showing that guys are clueless on the subtleties of nonverbal cues from women, taking a subtle smile as a sexual come-on, for instance.

Up is where we go from here

The question confronting us today is: who owns the Geosynchronous Orbit?

In recent years, “parking spots” in the geosynchronous orbit have become an increasingly hot commodity. According to the NASA, since the launch of the first television satellite into a geosynchronous orbit in 1964, the number of objects in Earth’s orbit has steadily increased to over 200 new additions per year. This increase was initially fueled by the Cold War, during which space was a prime area of competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. Yet over two decades after the end of the US-Soviet space race, even the global financial crisis that began in 2007 does not seem to have diminished the demand for telecommunications satellites positioned in GSO. This ongoing scramble to place satellites in GSO prompted some developing equatorial countries to assert sovereignty over the outer space “above” their territorial borders, presumably with the hope of extracting rent from the developed countries that circulate their technologies overhead. So far, the international community has rejected this notion, but the legal status of the GSO remains in limbo.

photo { Roman Signer }

‘In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.’ –R. W. Emerson

Intense emotional experiences frequently occur with bodily sensations such as a rapid heart rate or gastrointestinal distress.

It appears that bodily sensation (interoception) can be an important source of information when judging one’s emotional. How the brain processes interoception is becoming better understood.

However, how the brain integrates interoceptive signals with other brain emotional processing circuits is less well understood.

Terasawa and colleagues from Japan recently presented results of their research on this interaction of interoception and emotion.

photo { Matthew Genitempo }

Then: Xanthos! Xanthos! Xanthos!

{ I’d like to introduce a paper published last year in the journal Aquatic Mammals, which reports on two separate playful and – as you’ll see – uplifting encounters between bottlenose dolphins and humpback whales. | AnimalWise| full story }

‘Death is not the worst that can happen to men.’ –Plato

After four decades of largely unfulfilled hopes—Dec. 23 marks 40 years since President Nixon declared war on cancer—scientists have hit on a potential cure that few thought possible a few years ago: vaccines. If they succeed, cancer vaccines would revolutionize treatment. They could spell the end of chemotherapy and radiation, which can have horrific side effects, which tumor cells often become resistant to, and which often make so little difference it would be laughable were it not so tragic: last week, for instance, headlines touted two new drugs for metastatic breast cancer even though studies failed to show that they extend survival by a single day. Vaccines could make such “advances” a thing of the past. And they could make cancer as preventable, with a few jabs, as measles.

“Could” is the key word. Cancer vaccines are still being tested. Patients, doctors, and scientists know only too well that seemingly wondrous cancer therapies can flame out. But progress is accelerating. In 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first-ever tumor vaccine, called Provenge, to treat prostate cancer. Scores of other vaccines are in the pipeline. Over the summer, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania unveiled what they call a cancer “breakthrough 20 years in the making”: a vaccine against chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that has brought about remissions of up to a year and counting—and which its inventors believe can be tweaked to attack lung cancer, ovarian cancer, myeloma, and melanoma. Vaccines against pancreatic and brain cancer are also being tested. “For the first time,” says Disis, who has a $7.9 million grant from the Pentagon to develop a preventive vaccine, “clinical trials [of cancer vaccines] are demonstrating anti-tumor efficacy in numbers of patients with cancer, not just one or two unique individuals.”

Ever of thee, Anne Lynch, he’s deeply draiming!

Scientists at the University of Sheffield believe decision making mechanisms in the human brain could mirror how swarms of bees choose new nest sites.

Striking similarities have been found in decision making systems between humans and insects in the past but now researchers believe that bees could teach us about how our brains work.

Sitting pretty over his Oyster Monday print face

How to Gamble If You’re In a Hurry

The beautiful theory of statistical gambling, started by Dubins and Savage (for subfair games) and continued by Kelly and Breiman (for superfair games) has mostly been studied under the unrealistic assumption that we live in a continuous world, that money is indefinitely divisible, and that our life is indefinitely long.

Here we study these fascinating problems from a purely discrete, finitistic, and computational, viewpoint, using Both Symbol-Crunching and Number-Crunching (and simulation just for checking purposes).