science

Several studies suggest that memories can be pharmaceutically dampened. For example, researchers recently showed that a drug called ZIP causes cocaine-addicted rats to forget the locations where they had regularly been receiving cocaine. Other drugs, already tested in humans, may ease the emotional pain associated with memories of traumatic events.

Many are alarmed by the prospect of pharmaceutical memory manipulation. In this brief comment, I argue that these fears are overblown. Thoughtful regulation may someday be appropriate, but excessive hand-wringing now over the ethics of tampering with memory could stall research into promising methods of preventing and treating post-traumatic stress.

{ SSRN | Continue reading }

photo { Nigel Shafran, Moonflower, 1990 }

drugs, memory, neurosciences, photogs | March 23rd, 2012 1:58 pm

Neuroscientists know that the brain contains some 100 billion neurons and that the neurons are joined together via an estimated quadrillion (one million billion) connections. It’s through those links that the brain does the remarkable work of learning and storing memory. Yet scientists have never mapped that whole web of neural contact, known as the connectome. It would be as if doctors knew about each of our bones in isolation but had never seen an entire skeleton. The sheer complexity of the connectome has put such a map out of reach until now.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

related { Is a project to map the brain’s full communications network worth the money? }

illustration { Trevor Brown }

brain, neurosciences | March 23rd, 2012 12:01 pm

flashback, science, visual design | March 23rd, 2012 11:24 am

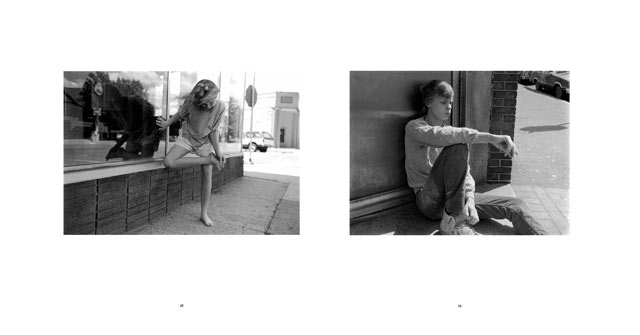

People with autism have a greater than normal capacity for processing information even from rapid presentations and are better able to detect information defined as ‘critical’, according to a study published today in the ‘Journal of Abnormal Psychology’. The research may help to explain the apparently higher than average prevalence of people with autism spectrum disorders in the IT industry.

{ Wellcome Trust | Continue reading }

related { Learning best when you rest: Sleeping after processing new info most effective, new study shows }

photos { Mark Steinmetz }

neurosciences | March 23rd, 2012 10:07 am

new york, science | March 22nd, 2012 7:33 am

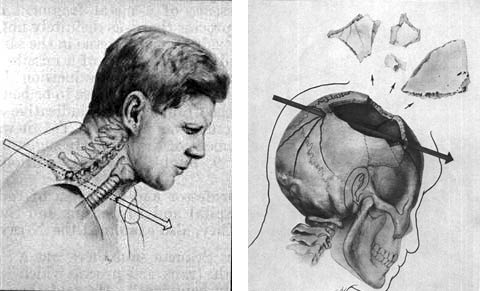

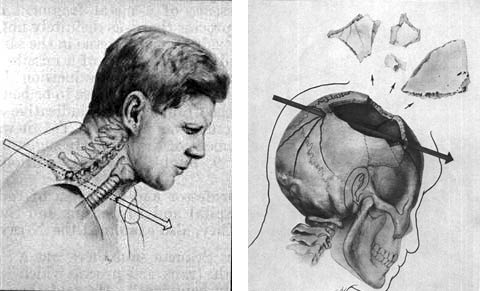

{ 1. Medical drawing of a cross-section of President Kennedy’s neck and chest, showing the trajectory of the projectile from back to throat. | 2. Diagram showing the trajectory of the missile through President Kennedy’s skull. The skull fragments are shown exploded for illustrative purposes; most stayed attached to the skull by skin flaps. | John F. Kennedy autopsy | Wikipedia }

U.S., flashback, science | March 22nd, 2012 7:20 am

This new research provides a terrific reference list of prior work done on women stalkers and reports a high rate of psychosis among women stalkers. Delusions are the most common symptom in two of the three major studies completed so far. Half of the women stalkers described in prior research had character disorders and women were more likely than men to target a former professional contact (like mental health professionals, teachers or lawyers). It appears that male stalkers are less particular, and more likely to target strangers. Women stalkers seek intimacy.

{ Keen Trial | Continue reading }

photo { Taylor Radelia }

psychology, relationships, weirdos | March 21st, 2012 2:46 pm

While sex purges our genome of harmful mutations and pushes biodiversity, it’s a costly exercise for the average organism. (…)

Their new estimates for the origins of reliable eukaryotic fossils now rest at 1.78 to 1.68 billion years ago, and this is where we must currently park the idea of when sex first became popular.

The age-old question that follows is why did sexual reproduction begin? Why didn’t life just keep evolving through cloning and asexual budding systems? (…)

Sex is not an efficient way of sharing genes. When we mate sexually we combine only 50% of our genetic material with our partner’s, whereas asexually budding organisms have 100% of their genetic material carried into the next generation. And Otto highlights what biologists call the ‘cost’ of sex, in that sexually reproducing organisms need to produce twice as many offspring as asexual organisms or they lose out in the population race.

Despite these drawbacks, evolution has shaped the living world in such a way that few large creatures today actually reproduce asexually (only about 0.1% of all living organisms, excluding bacteria). Sex generates variation, and that is certainly a good thing when dealing with constant and unpredictable changes in our environment.

{ Cosmos | Continue reading }

genes, science, sex-oriented | March 20th, 2012 12:51 pm

By all rights, sex shouldn’t exist. Ask most non-biologists what sex is “for,” and they’d probably answer “reproduction,” but they’d be wrong.

In fact, sex is quite simply a terrible way to reproduce.

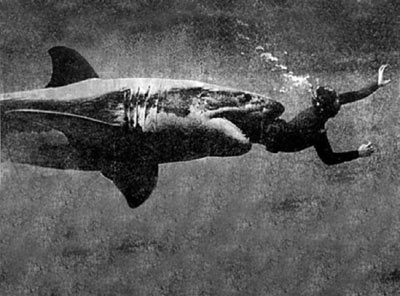

The reality is that living things can easily make babies without sex, and many do just that. Lots of animals breed asexually, via parthenogenesis (development of an unfertilized egg, without any involvement by males); the list includes many insects, crustaceans, rotifers, flatworms, snails, even some vertebrates including certain species of shark, lizard and the occasional bird. And it’s quite common in plants.

The evolutionary conundrum is that compared to asexual reproduction, breeding sexually poses a daunting number of disadvantages, so many, in fact, that a number of highly regarded evolutionary theorists have concluded rather glumly that sex may actually be a biological liability, something that we—and other species as well—are regrettably stuck with.

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

sculpture { Bernini, The Rape of Proserpina, 1621-22 }

science, sex-oriented | March 20th, 2012 12:33 pm

Researchers at Yale University have developed a new way of seeing inside solid objects, including animal bones and tissues, potentially opening a vast array of dense materials to a new type of detailed internal inspection.

The technique, a novel kind of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), creates three-dimensional images of hard and soft solids based on signals emitted by their phosphorus content.

Traditional MRI produces an image by manipulating an object’s hydrogen atoms with powerful magnets and bursts of radio waves. The atoms absorb, then emit the radio wave energy, revealing their precise location. A computer translates the radio wave signals into images. Standard MRI is a powerful tool for examining water-rich materials, such as anatomical organs, because they contain a lot of hydrogen. But it is hard to use on comparatively water-poor solids, such as bone.

The Yale team’s method targets phosphorus atoms rather than hydrogen atoms, and applies a more complicated sequence of radio wave pulses.

{ Yale News | Continue reading }

artwork { Trevor Brown, Teddy Bear Operation, 2008 }

science, technology | March 19th, 2012 5:19 pm

mathematics, photogs | March 19th, 2012 3:30 pm

A team of researchers that includes a USC scientist has methodically demonstrated that a face’s features or constituents – more than the face per se – are the key to recognizing a person.

Their study, which goes against the common belief that brains process faces “holistically,” appears this month in Psychological Science.

In addition to shedding light on the way the brain functions, these results may help scientists understand rare facial recognition disorders.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Thomas Prior }

faces, neurosciences, photogs | March 19th, 2012 3:18 pm

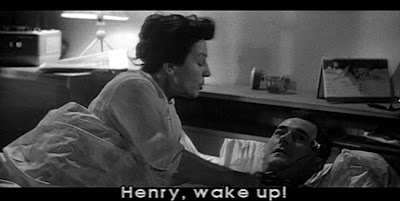

Several theories claim that dreaming is a random by-product of REM sleep physiology and that it does not serve any natural function.

Phenomenal dream content, however, is not as disorganized as such views imply. The form and content of dreams is not random but organized and selective: during dreaming, the brain constructs a complex model of the world in which certain types of elements, when compared to waking life, are underrepresented whereas others are over represented. Furthermore, dream content is consistently and powerfully modulated by certain types of waking experiences.

On the basis of this evidence, I put forward the hypothesis that the biological function of dreaming is to simulate threatening events, and to rehearse threat perception and threat avoidance.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we need to consider the original evolutionary context of dreaming and the possible traces it has left in the dream content of the present human population. In the ancestral environment, human life was short and full of threats. Any behavioral advantage in dealing with highly dangerous events would have increased the probability of reproductive success. A dream-production mechanism that tends to select threatening waking events and simulate them over and over again in various combinations would have been valuable for the development and maintenance of threat-avoidance skills.

Empirical evidence from normative dream content, children’s dreams, recurrent dreams, nightmares, post traumatic dreams, and the dreams of hunter-gatherers indicates that our dream-production mechanisms are in fact specialized in the simulation of threatening events, and thus provides support to the threat simulation hypothesis of the

{ Antti Revonsuo/Behavioral and Bain Sciences | PDF }

archives, psychology, science, theory | March 19th, 2012 3:02 pm

According to a paper just published (but available online since 2010), we haven’t found any genes for personality.

The study was a big meta-analysis of a total of 20,000 people of European descent. In a nutshell, they found no single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with any of the “Big 5″ personality traits of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness. There were a couple of very tenuous hits, but they didn’t replicate.

Obviously, this is bad news for people interested in the genetics of personality.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

image { Pole Edouard }

genes, psychology | March 19th, 2012 12:15 pm

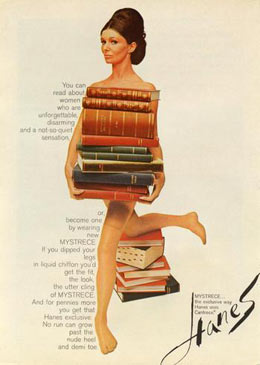

New support for the value of fiction is arriving from an unexpected quarter: neuroscience.

Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters. Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life.

Researchers have long known that the “classical” language regions, like Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, are involved in how the brain interprets written words. What scientists have come to realize in the last few years is that narratives activate many other parts of our brains as well, suggesting why the experience of reading can feel so alive. Words like “lavender,” “cinnamon” and “soap,” for example, elicit a response not only from the language-processing areas of our brains, but also those devoted to dealing with smells. (…)

Researchers have discovered that words describing motion also stimulate regions of the brain distinct from language-processing areas. (…)

The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life; in each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated. (…) Fiction — with its redolent details, imaginative metaphors and attentive descriptions of people and their actions — offers an especially rich replica. Indeed, in one respect novels go beyond simulating reality to give readers an experience unavailable off the page: the opportunity to enter fully into other people’s thoughts and feelings. (…) Scientists call this capacity of the brain to construct a map of other people’s intentions “theory of mind.” Narratives offer a unique opportunity to engage this capacity, as we identify with characters’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers. (…)

Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined.

{ NYT | Continue reading }

books, neurosciences, psychology | March 19th, 2012 12:10 pm

Previous studies identified a number of common cycling injuries, including neck and back pain, chafing, and genital numbness. In fact, 50 to 91% of men and women cyclists report experiencing genital numbness. The relationship between bicycle setup and genital sensation in women cyclists, however, has, until now, not been investigated.

In order to study this relationship, scientists (…) recruited 41 female cyclists who rode an average of at least 10 miles per week, and who positioned their handlebars lower than or level with the saddle. (…)

The Medoc Vibratory Sensory Analyzer 3000, not your average vibrator, was used to measure sensation at eight genital regions: the clitoris, the left and right perineum, the anterior and posterior vagina, the left and right labia, and the urethra.

(…)

This increase in perineum saddle pressure resulted in a significant loss of genital sensation in the anterior vagina and in the left labia, where the threshold at which women were able to sense genital stimulation increased by 34% and 29% respectively in women with lower handlebars.

{ Salamander Hours | Continue reading }

leisure, science, sex-oriented, transportation | March 19th, 2012 12:00 pm

University of Alberta study explores women’s experiences of public change rooms and locker rooms; finds many don’t relish the experience of being naked in front of others.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

In recent years, a small number of researchers have been working to develop the science of post-coitus.

{ Salon | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships, sex-oriented | March 16th, 2012 3:52 pm

The extraordinary ability of birds and bats to fly at speed through cluttered environments such as forests has long fascinated humans. It raises an obvious question: how do these creatures do it?

Clearly they must recognise obstacles and exercise the necessary fine control over their movements to avoid collisions while still pursuing their goal. And they must do this at extraordinary speed.

From a conventional command and control point of view, this is a hard task. Object recognition and distance judgement are both hard problems and route planning even tougher.

Even with the vast computing resources that humans have access to, it’s not at all obvious how to tackle this problem. So how flying animals manage it with immobile eyes, fixed focus optics and much more limited data processing is something of a puzzle.

Today, Ken Sebesta and John Baillieul at Boston University reveal how they’ve cracked it. These guys say that flying animals use a relatively simple algorithm to steer through clutter and that this has allowed them to derive a fundamental law that determines the limits of agile flight.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

birds, science, technology | March 16th, 2012 3:22 pm

The hippocampus is the part of the brain that’s responsible for learning, storing memories and associating them with feelings and emotions. Within the hippocampus lies the dentate gyrus, which is where adult neurogenesis takes place — the formation of new neurons throughout adulthood. The middle layer of the dentate gyrus contains a type of neurons called granule cells. These are constantly generated and take a few weeks to develop and integrate in the dentate gyrus network.

Marin-Burgin et al. asked the following question:

Is it solely the continuous addition of new neurons to the network that is important, or are there specific functional properties only attributable to new granule cells (GCs) that are relevant to information processing?

{ Chimeras | Continue reading }

brain, memory, neurosciences | March 16th, 2012 3:00 pm

Even after discovering and confirming a new species of plant, which is trying enough itself, botanists have to submit a description in Latin — even if they had never studied the language before — and ensure that said description is published in a journal printed on real paper.

That is until New Years Day 2012, when new rules passed at the International Botanical Congress in Melbourne, Australia this July, take effect: the botanists voted on a measure to leave the lengthy and time-consuming descriptions behind. Additionally, the group released their concerns about the impermanence of electronic publication, and will now allow official descriptions to be set in online-only journals.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Mapplethorpe, Double Jack in the Pulpit, 1988 }

Botany, science | March 15th, 2012 2:16 pm