science

It has been conjectured that individuals may be left-brain dominant or right-brain dominant based on personality and cognitive style, but neuroimaging data has not provided clear evidence whether such phenotypic differences in the strength of left-dominant or right-dominant networks exist.

{ Thoughts on Thoughts | Continue reading }

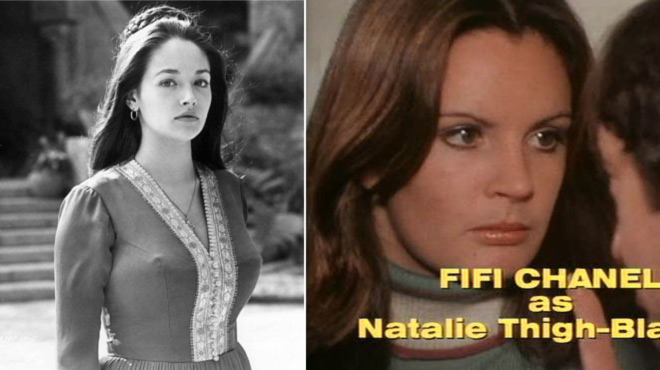

images { Bernhard Handick | 2 }

brain | August 24th, 2013 2:19 pm

As it turns out, high-functioning sociopaths are full of handy lifestyle tips. […]

After being hired at an elite law firm, Ms Thomas exploited her company’s “non-existent” vacation policy by taking long weekends and lengthy vacations abroad. “People were implicitly expected not to take vacations, but I had my own lifelong policy of following only explicit rules, and then only because they’re easiest to prove against me,” she explains.

How to apply to your own life: Ignore “suggested donation” pleas at museums, always help yourself to more food and drinks at dinner parties and recline your seat all the way back when flying. […]

Ms Thomas’s opportunism applies to the social as much as the professional realm. “I have learned that it is important always to have a catalogue of at least five personal stories of varying length in order to avoid the impulse to shoehorn unrelated titbits into existing conversations,” she writes. “Social-event management feels very much like classroom or jury management to me; it’s all about allowing me to present myself to my own best advantage.” […]

One of Ms Thomas’s favourite activities is attending academic conferences. Since she doesn’t teach at a top-tier school, she captures her colleagues’ attention by other means: “Everything about the way I present myself is extremely calculated,” she writes. “I am careful to wear something that will draw attention, like jeans and cowboy boots while everyone else is wearing business attire.” The goal, Ms Thomas says, is “to indicate that I’m not interested in being judged by the usual standards.”

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

guide, psychology | August 21st, 2013 2:43 pm

The economics of “happiness” shares a feature with behavioral economics that raises questions about its usefulness in public policy analysis. What happiness economists call “habituation” refers to the fact that people’s reported well-being reverts to a base level, even after major life events such as a disabling injury or winning the lottery. What behavioral economists call “projection bias” refers to the fact that people systematically mistake current circumstances for permanence, buying too much food if shopping while hungry for example. Habituation means happiness does not react to long-term changes, and projection bias means happiness over-reacts to temporary changes. I demonstrate this outcome by combining responses to happiness questions with information about air quality and weather on the day and in the place where those questions were asked. The current day’s air quality affects happiness while the local annual average does not. Interpreted literally, either the value of air quality is not measurable using the happiness approach or air quality has no value. Interpreted more generously, projection bias saves happiness economics from habituation, enabling its use in public policy.

{ National Bureau of Economic Research }

economics, ideas, psychology | August 21st, 2013 3:26 am

Researchers at the University of Kentucky were interested in the link between low glucose levels and aggressive behavior… […]

When you go several hours without eating, your blood sugar drops. Once it falls below a certain point, glucose-sensing neurons in your ventromedial hypothalamus, a brain region involved in feeding, are notified and activated resulting in level fluctuations of several different hormones. Ghrelin, a hormone that increases expression when blood sugar gets low and stimulates appetite through actions of the hypothalamus, has been shown to block the release of the neurotransmitter serotonin. The serotonin system is incredibly complex and contributes to a number of different central nervous system functions. One of the many hats this neurotransmitter wears is modulation of emotional state, including aggression. […]

If you have a predisposition to aggression, low serotonin levels circulating in your brain may lead to altered communications between brain regions that wrangle aggressive behavior.

{ Synaptic Scoop | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, neurosciences, psychology | August 19th, 2013 5:02 pm

Many scholars have argued that Nietzsche’s dementia was caused by syphilis. A careful review of the evidence suggests that this consensus is probably incorrect. The syphilis hypothesis is not compatible with most of the evidence available. Other hypotheses – such as slowly growing right-sided retro-orbital meningioma – provide a more plausible fit to the evidence.

{ Journal of Medical Biography | PDF }

From his late 20s onward, Nietzsche experienced severe, generally right- sided headaches. He concurrently suffered a progressive loss of vision in his right eye and developed cranial nerve findings that were documented on neurological examinations in addition to a disconjugate gaze evident in photographs. His neurological findings are consistent with a right-sided frontotemporal mass. In 1889, Nietzsche also developed a new-onset mania which was followed by a dense abulia, also consistent with a large frontal tumor. […] An intracranial mass may have been the etiology of his headaches and neurological findings and the cause of his ultimate mental collapse in 1889.

{ Neurosurgery | PDF }

brain, health, nietzsche, science | August 18th, 2013 11:01 am

guide, psychology | August 15th, 2013 2:49 pm

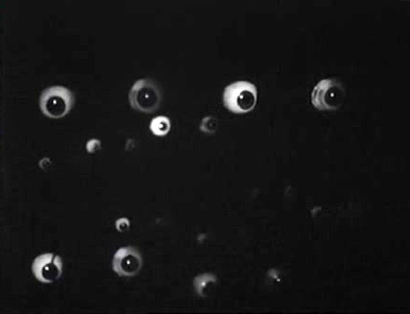

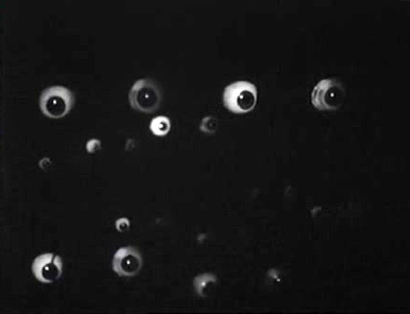

At this very moment, your eyes and brain are performing an astounding series of coordinated operations.

Light rays from the screen are hitting your retina, the sheet of light-sensitive cells that lines the back wall of each of your eyes. Those cells, in turn, are converting light into electrical pulses that can be decoded by your brain.

The electrical messages travel down the optic nerve to your thalamus, a relay center for sensory information in the middle of the brain, and from the thalamus to the visual cortex at the back of your head. In the visual cortex, the message jumps from one layer of tissue to the next, allowing you to determine the shape and color and movement of the thing in your visual field. From there the neural signal heads to other brain areas, such as the frontal cortex, for yet more complex levels of association and interpretation. All of this means that in a matter of milliseconds, you know whether this particular combination of light rays is a moving object, say, or a familiar face, or a readable word. […]

This post is about a question that’s long been debated among scientists and philosophers: At what point in that chain of operations does the visual system begin to integrate information from other systems, like touches, tastes, smells, and sounds? What about even more complex inputs, like memories, categories, and words?

We know the integration happens at some point. If you see a lion running toward you, you will respond to that sight differently depending on if you are roaming alone in the Serengeti or visiting the zoo. Even if the two sights are exactly the same, and presenting the same optical input to your retinas, your brain will use your memories and knowledge to put your vision into context

{ Virginia Hughes/National Geographic | Continue reading }

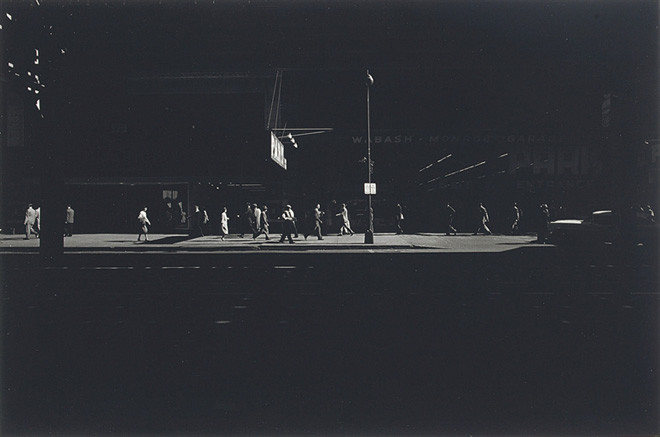

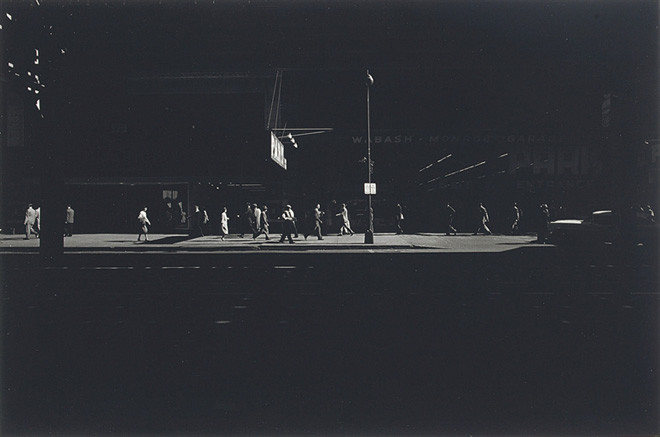

photo { Harry Callahan }

eyes, neurosciences | August 15th, 2013 8:45 am

A surge of electrical activity in the brain could be responsible for the vivid experiences described by near-death survivors, scientists report.

A study carried out on dying rats found high levels of brainwaves at the point of the animals’ demise.

US researchers said that in humans this could give rise to a heightened state of consciousness.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

mystery and paranormal, science | August 13th, 2013 5:58 am

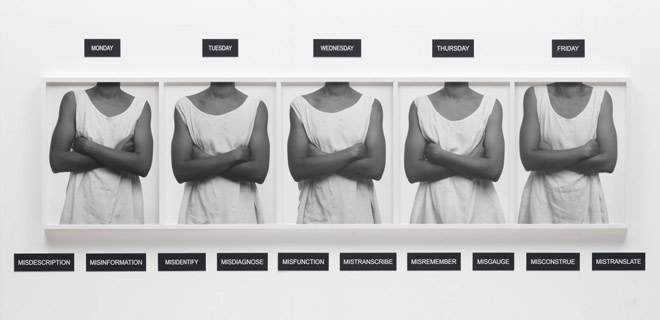

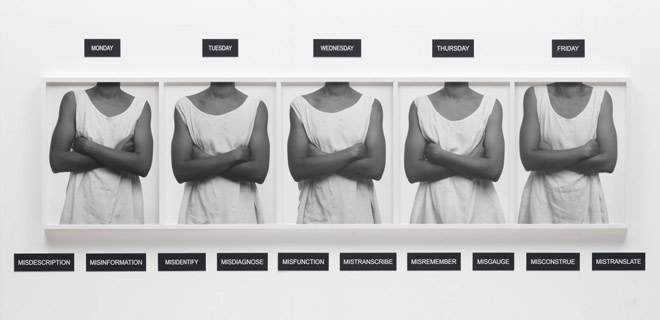

In two experiments we showed that exposure to an incidental black and white visual contrast leads people to think in a “black and white” manner, as indicated by more extreme moral judgments.

Participants who were primed with a black and white checkered background while considering a moral dilemma (Experiment 1) or a series of social issues (Experiment 2) gave ratings that were significantly further from the response scale’s mid-point, relative to participants in control conditions without such priming.

These findings suggest that in addition to affective cues and gut feelings, non-affective cues relating to processing style can influence moral judgments.

{ ScienceDirect }

art { Lorna Simpson }

psychology | August 7th, 2013 11:45 am

In human psychology, overconfidence is typically taken to be the overestimation of one’s own capabilities. This, and other apparent cognitive biases such as optimism, are well-documented phenomena whose underlying neural mechanisms are becoming known. However, a convincing evolutionary explanation of such phenomena is lacking.

Two recent high-profile publications have advanced proposals for evolutionary explanations of overconfidence. […] The first proposal, a model by Johnson and Fowler (J&F), […] considers a scenario in which individuals compare their estimated fighting ability against that of potential opponents when deciding whether to contest a resource, doing so only if they perceive themselves as more capable. By identifying conditions under which individuals should overestimate their fighting ability, J&F claim to show that overconfidence should evolve.

The second is Trivers’ theory of self-deception. […] Among Trivers’ primary arguments for the evolution of cognitive bias are that selective pressure exists for animals to deceive each other and that deception is more effective, and less cognitively costly, when the deceiver believes the deception; in the context of animal conflict, the explanation of overconfidence would be that acting as if one’s abilities are greater than they really are can more effectively dissuade others from competition.

[…]

We argue that recent proposals, focused on benefits from overestimating the probability of success in conflicts or practicing self-deception to better deceive others, are still lacking in crucial regards. Attention must be paid to the difference between cognitive and outcome biases; outcome biases are suboptimal, yet cognitive biases can be optimal.

[…]

Cognitive bias: an inaccurate view of the world. This is a psychological definition. A cognitive bias might produce rational behavior or might result in an outcome bias.

Outcome bias: a departure from rational behavior. This is an operational definition.

{ Cell | PDF }

psychology | August 7th, 2013 7:07 am

Sex pheromones are chemical compounds released by an animal that attract animals of the same species but opposite sex. They are often so specific that other species can’t smell them at all, which makes them useful as a secret communication line for just that species. But this specificity raises an intriguing question: When a new species evolves and uses a new pheromone signaling system, what comes first: the ability to make the pheromone or the ability to perceive it? […]

Any individuals that make a new and different scent would then be perceived by the receivers as being the wrong species and they won’t attract any mates. If you don’t attract mates, you can’t pass on your new genes for your new scent. This produces a strong pressure to make a scent that is as similar as the scent produced by everyone else as possible (this is called stabilizing selection). With this intense pressure to be like everyone else, how did the incredible diversity of species-specific pheromones come to be?

{ Nature | Continue reading }

animals, olfaction, science | August 7th, 2013 6:05 am

The prevailing view in psychology is that materialism is bad for our well-being. Research by Tim Kasser (at Knox College) and others has revealed an association between holding materialist values and being more depressed and selfish, and having poorer relationships. Kasser has previously called for a revolution in Western culture, shifting us from a thing-centred to a person-centred society. Other research by Leaf Van Boven, Thomas Gilovich and colleagues has shown that the purchase of experiences leaves people happier than buying material products. In another study of theirs, materialistic people were liked less than people who appeared more interested in experiences.

{ The Psychologist | PDF }

images { 1 | 2 }

psychology | August 6th, 2013 2:12 am

Analyzing data from 60 earlier studies, Solomon Hsiang from the University of California, Berkeley, found that warmer temperatures and extremes in rainfall can substantially increase the risk of many types of conflict. For every standard deviation of change, levels of interpersonal violence, such as domestic violence or rape, rise by some 4 percent, while the frequency of intergroup conflict, from riots to civil wars, rise by 14 percent. Global temperatures are expected to rise by at least two standard deviations by 2050, with even bigger increases in the tropics.

{ The Scientist | Continue reading }

climate, fights | August 6th, 2013 2:07 am

Since the size, density, and even shape of a person’s skull is somewhat unique, that resonance will vary across individuals. Our current research was designed to explore whether this uniqueness in skull resonance might have a direct influence on the kinds of music a person prefers. […] this research suggests that the skull [shape and size] might influence the music that a person dislikes rather than the music a person likes.

{ Acoustical Society of America/Improbable | Continue reading }

music, science | August 5th, 2013 11:37 am

In the middle of the 20th century, experimental psychologists began to notice a strange interaction between human vision and time. If they showed people flashes of light close together in time, subjects experienced the flashes as if they all occurred simultaneously. When they asked people to detect faint images, the speed of their subjects’ responses waxed and waned according to a mysterious but predictable rhythm. Taken together, the results pointed to one conclusion: that human vision operates within a particular time window – about 100 milliseconds, or one-tenth of a second.

[…] Pretty much anyone with a pair of eyes will tell you that vision feels smooth and unbroken. But is it truly as continuous as it feels, or might it occur in discrete chunks of time?

{ Garden of the Mind | Continue reading }

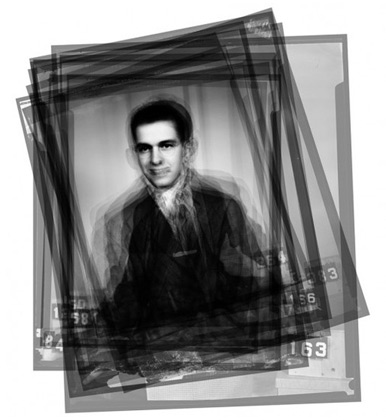

screenshot { Ivan Mozzhukhin, Le brasier ardent, 1923 }

eyes, time | August 5th, 2013 5:53 am

“Never give up” has become one of the most popular pieces of advice in Western culture.[…] Many worthwhile goals require serious commitment and perseverance in order to achieve them. The problem with this advice is that at some point in our lives, we all have goals that are unattainable, and this is where “never give up” falls short. […]

Results showed that the tendency to disengage from unattainable goals was associated with lower life stress, fewer intrusive thoughts about one’s problems, and feeling more control over one’s life. The flip side of this is that the tendency to stay engaged with unattainable goals was associated with more stress, more intrusive thoughts, and feeling less control.

{ Psych Your Mind | Continue reading }

guide, psychology | August 3rd, 2013 12:49 pm

The pressures and expectations of the market weigh heavily on everyone. The erosion of long-term stability in employment means that people are expected to throw themselves into any job they find. Every minor task or training exercise must be met with absolute enthusiasm, as if motivation were something that could be turned on or off at will.

Such behaviour is impossible to sustain, and exacts its toll: depressive feelings, physical and emotional exhaustion at the expenditure of energy on projects we care little about.

Motivation loses its roots in our childhood interests and ideals, and becomes something external to us. Hence the oscillation between hyper-motivation and depletion characteristic of the contemporary worker.

{ The Guardian | Continue reading }

art { Kevin Barton }

economics, psychology | July 29th, 2013 4:06 pm

On a street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, an unremarkable gray box protrudes from a telephone pole. Inside the box lies a state-of-the-art airflow-sampling device, one part of an experiment to track how a gas disperses through the city’s streets and subway system. […]

The goal of the project is to develop a model for how a dangerous airborne contaminant, such as sarin gas or anthrax, would spread throughout the city in the event of a terrorist attack or accidental release.

The scientists released tiny amounts of a colorless, nontoxic gas at several locations around the city. The airflow samplers, located at various points throughout the city, measured the gas to determine how fast and how far it spread.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

unrelated { Eproctophilia is a paraphilia in which people are sexually aroused by flatulence. The following account presents a brief case study of an eproctophile. | Improbable }

crime, olfaction, technology | July 27th, 2013 5:39 am

First, about how glaciers turn into ocean water.

Consider this experiment. Take a large open-top drum of water and poke a hole near the bottom. Measure the rate at which water comes out of the hole. As the amount of water in the drum goes down, the rate of flow out of the hole will normally decrease because the amount of water pressure behind the hole decreases. Now, have a look at a traditional hourglass, where sand runs from an upper chamber which slowly empties into a lower chamber which slowly fills. If you measure the rate of sand flow through the connecting hole, does it decrease in flow rate because there is, over time, less sand in the upper chamber? I’ll save you the trouble of carrying out the experiment. No, it does not. This is because the movement of sand from the upper to lower parts of an hourglass is an entirely different kind of phenomenon than the flow of water out of the drum. The former is a matter of granular material dynamics, the latter of fluid dynamics.

Jeremy Bassis and Suzanne Jacobs have recently published a study that looks at glacial ice as a granular material, modeling the ice as clumped together ice boulders that interact with each other either by sticking together or, over time, coming apart at fracture lines. This is important because, according to Bassis, about half of the water that continental glaciers provide to the ocean comes in the form of ice melting (with the water running off) but the other half consists of large chunks (icebergs) that come off in a manner that has been very hard to model.

{ Greg Laden/ScienceBlogs | Continue reading }

science, water | July 24th, 2013 3:46 am

For a couple years now I’ve been fascinated by some recent ideas about how complexity evolves. Darwin’s great insight was recognizing how natural selection could create complex traits. All that was needed was a series of intermediates that raised the reproductive success of organisms. But recently some researchers have developed ideas in which natural selection doesn’t play such a central role.

One idea, laid out in the book Biology’s First Law, holds that life has a built-in propensity to get more complex–even in the absence of natural selection. According to another idea, called constructive neutral evolution, mutations can change simple structures into more complex ones even if those mutations don’t provide an advantage. The scientists who are championing these ideas don’t see them as refuting natural selection, but, rather, complementing it, and enriching our understanding of how evolution works.

{ Carl Zimmer | Continue reading | More: Scientists are exploring how organisms can evolve elaborate structures without Darwinian selection }

science, theory | July 17th, 2013 9:20 am