‘The History of the world is none other than the progress of the consciousness of Freedom.’ –Hegel

At this very moment, your eyes and brain are performing an astounding series of coordinated operations.

Light rays from the screen are hitting your retina, the sheet of light-sensitive cells that lines the back wall of each of your eyes. Those cells, in turn, are converting light into electrical pulses that can be decoded by your brain.

The electrical messages travel down the optic nerve to your thalamus, a relay center for sensory information in the middle of the brain, and from the thalamus to the visual cortex at the back of your head. In the visual cortex, the message jumps from one layer of tissue to the next, allowing you to determine the shape and color and movement of the thing in your visual field. From there the neural signal heads to other brain areas, such as the frontal cortex, for yet more complex levels of association and interpretation. All of this means that in a matter of milliseconds, you know whether this particular combination of light rays is a moving object, say, or a familiar face, or a readable word. […]

This post is about a question that’s long been debated among scientists and philosophers: At what point in that chain of operations does the visual system begin to integrate information from other systems, like touches, tastes, smells, and sounds? What about even more complex inputs, like memories, categories, and words?

We know the integration happens at some point. If you see a lion running toward you, you will respond to that sight differently depending on if you are roaming alone in the Serengeti or visiting the zoo. Even if the two sights are exactly the same, and presenting the same optical input to your retinas, your brain will use your memories and knowledge to put your vision into context

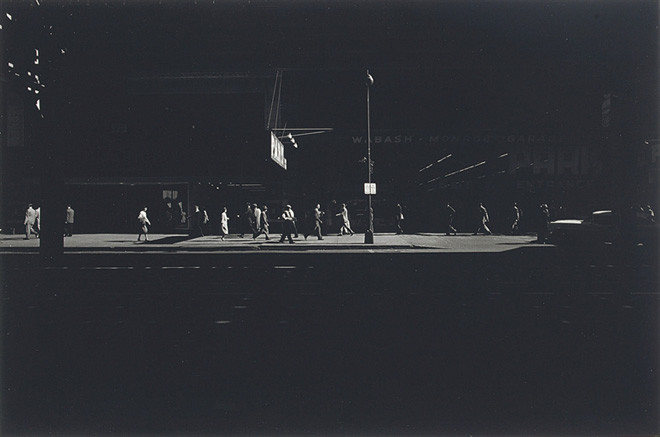

photo { Harry Callahan }