brain

Deisseroth is developing a remarkable way to switch brain cells off and on by exposing them to targeted green, yellow, or blue flashes. With that ability, he is learning how to regulate the flow of information in the brain.

Deisseroth’s technique, known broadly as optogenetics, could bring new hope to his most desperate patients. In a series of provocative experiments, he has already cured the symptoms of psychiatric disease in mice. Optogenetics also shows promise for defeating drug addiction. […]

For all its complexity, the brain in some ways is a surprisingly simple device. Neurons switch off and on, causing signals to stop or go. Using optogenetics, Deisseroth can do that switching himself. He inserts light-sensitive proteins into brain cells. Those proteins let him turn a set of cells on or off just by shining the right kind of laser beam at the cells.

That in turn makes it possible to highlight the exact neural pathways involved in the various forms of psychiatric disease. A disruption of one particular pathway, for instance, might cause anxiety.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

brain, health, neurosciences, science, technology | September 27th, 2012 12:43 pm

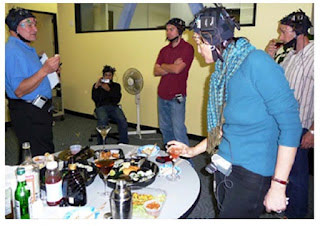

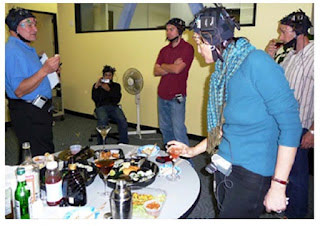

{ Alan Gevins and colleagues of San Francisco took electroencephalography (EEG) out of the lab and organized an EEG party - allowing them to record brain electrical activity from 10 people as they chatted and drank vodka martinis. The purpose of the study was to measure the effect of alcohol on brain activity. | Neuroskeptic | full story }

brain, food, drinks, restaurants, neurosciences | September 11th, 2012 3:02 pm

I often have to cut into the brain and it is something I hate doing. With a pair of short-wave diathermy forceps I coagulate a few millimetres of the brain’s surface, turning the living, glittering pia arachnoid – the transparent membrane that covers the brain – along with its minute and elegant blood vessels, into an ugly scab. With a pair of microscopic scissors I then cut the blood vessels and dig downwards with a fine sucker. I look down the operating microscope, feeling my way through the soft white substance of the brain, trying to find the tumour.

{ Henry Marsh/Granta | Continue reading }

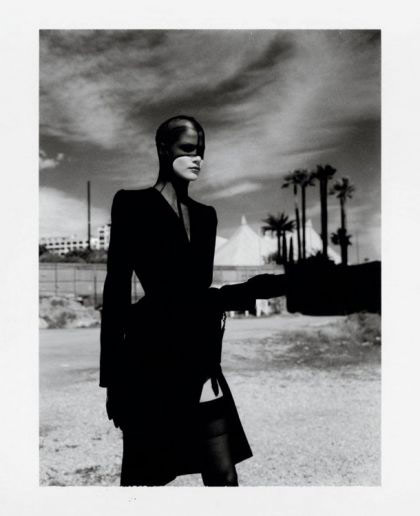

photo { Helmut Newton }

brain, experience, health | September 4th, 2012 1:38 pm

Consciousness is restricted to a subset of animals with relatively complex brains. The more scientists study animal behavior and brain anatomy, however, the more universal consciousness seems to be. A brain as complex as the human brain is definitely not necessary for consciousness. On July 7 this year, a group of neuroscientists convening at Cambridge University signed a document officially declaring that non-human animals, “including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses” are conscious.

Humans are more than just conscious—they are also self-aware. Scientists differ on the difference between consciousness and self-awareness, but here is one common explanation: […] To be conscious is to think; to be self-aware is to realize that you are a thinking being and to think about your thoughts. […]

Numerous neuroimaging studies have suggested that thinking about ourselves, recognizing images of ourselves and reflecting on our thoughts and feelings—that is, different forms self-awareness—all involve the cerebral cortex, the outermost, intricately wrinkled part of the brain. The fact that humans have a particularly large and wrinkly cerebral cortex relative to body size supposedly explains why we seem to be more self-aware than most other animals.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

animals, brain, neurosciences | August 26th, 2012 3:52 pm

Ancient Greek philosophers considered the ability to “know thyself” as the pinnacle of humanity. Now, thousands of years later, neuroscientists are trying to decipher precisely how the human brain constructs our sense of self.

Self-awareness is defined as being aware of oneself, including one’s traits, feelings, and behaviors. Neuroscientists have believed that three brain regions are critical for self-awareness: the insular cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the medial prefrontal cortex. However, a research team led by the University of Iowa has challenged this theory by showing that self-awareness is more a product of a diffuse patchwork of pathways in the brain – including other regions – rather than confined to specific areas. […]

“What this research clearly shows is that self-awareness corresponds to a brain process that cannot be localized to a single region of the brain,” said David Rudrauf, co-corresponding author of the paper, published online Aug. 22 in the journal PLOS ONE. “In all likelihood, self-awareness emerges from much more distributed interactions among networks of brain regions.”

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

art { Joshua Davis }

brain | August 22nd, 2012 4:43 pm

Research from Washington University in St. Louis has identified variations in brain scans that they believe identify portions of the brain that are responsible for intelligence.

As suspected brain size does play a small role; they said that brain size accounts for 6.7 percent of variance in intelligence. Recent research has placed the brain’s prefrontal cortex, a region just behind the forehead, as providing for 5 percent of the variation in intelligence between people.

The research from Washington University targets the left prefrontal cortex, and the strength of neural connections that it has to the rest of the brain. They think that these differences account for 10 percent of differences in intelligence among people. The study is the first to connect those differences to intelligence in people.

{ Medical Daily | Continue reading }

“Our research shows that connectivity with a particular part of the prefrontal cortex can predict how intelligent someone is,” suggests lead author Michael W. Cole. […]

One possible explanation of the findings, the research team suggests, is that the lateral prefrontal region is a “flexible hub” that uses its extensive brain-wide connectivity to monitor and influence other brain regions in a goal-directed manner.

“There is evidence that the lateral prefrontal cortex is the brain region that ‘remembers’ (maintains) the goals and instructions that help you keep doing what is needed when you’re working on a task,” Cole says. “So it makes sense that having this region communicating effectively with other regions (the ‘perceivers’ and ‘doers’ of the brain) would help you to accomplish tasks intelligently.”

{ Washington University in St. Louis | Continue reading }

images { 1 | 2 }

related { Women Score Higher on IQ Tests for the First Time in History }

brain | August 2nd, 2012 1:57 pm

At some point in evolution, our ancestors switched from walking on all four limbs to just two, and this transition to bipedalism led to what is referred to as the obstetric dilemma. The switch involved a major reconfiguration of the birth canal, which became significantly narrower because of a change in the structure of the pelvis. At around the same time, however, the brain had begun to expand.

One adaptation that evolved to work around the problem was the emergence of openings in the skull called fontanelles. The anterior fontanelle enables the two frontal bones of the skull to slide past each other, much like the tectonic plates that make up the Earth’s crust. This compresses the head during birth, facilitating its passage through the birth canal.

In humans, the anterior fontanelle remains open for the first few years of life, allowing for the massive increase in brain size, which occurs largely during early life. The opening gets gradually smaller as new bone is laid down, and is completely closed by about two years of age, at which time the frontal bones have fused to form a structure called the metopic suture. In chimpanzees and bononbos, by contrast, brain growth occurs mostly in the womb, and the anterior fontanelle is closed at around the time of birth.

{ Neurophilosophy/Guardian | Continue reading }

image { Lola Dupré }

brain, flashback, kids, science | July 18th, 2012 2:29 pm

A man sits in front of a computer screen sifting through satellite images of a foreign desert. The images depict a vast, sandy emptiness, marked every so often by dunes and hills. He is searching for man-made structures: houses, compounds, airfields, any sign of civilization that might be visible from the sky. The images flash at a rate of 20 per second, so fast that before he can truly perceive the details of each landscape, it is gone. He pushes no buttons, takes no notes. His performance is near perfect.

Or rather, his brain’s performance is near perfect. The man has a machine strapped to his head, an array of electrodes called an electroencephalogram, or EEG, which is recording his brain activity as each image skips by. It then sends the brain-activity data wirelessly to a large computer. The computer has learned what the man’s brain activity looks like when he sees one of the visual targets, and, based on that information, it quickly reshuffles the images. When the man sorts back through the hundreds of images—most without structures, but some with—almost all the ones with buildings in them pop to the front of the pack. His brain and the computer have done good work.

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

photo { Michel Le Belhomme }

brain, neurosciences, photogs, technology | July 12th, 2012 6:41 am

Research team at Aalto University and Turku PET Centre has revealed how experiencing strong emotions synchronizes brain activity across individuals.

Human emotions are highly contagious. Seeing others’ emotional expressions such as smiles triggers often the corresponding emotional response in the observer. Such synchronization of emotional states across individuals may support social interaction: When all group members share a common emotional state, their brains and bodies process the environment in a similar fashion.

Researchers at Aalto University and Turku PET Centre have now found that feeling strong emotions makes different individuals’ brain activity literally synchronous.

The results revealed that especially feeling strong unpleasant emotions synchronized brain’s emotion processing networks in the frontal and midline regions. On the contrary, experiencing highly arousing events synchronized activity in the networks supporting vision, attention and sense of touch.

{ Aalto University | Continue reading }

photo { Cypress Gardens, Florida, 1954 }

brain, neurosciences, relationships | May 24th, 2012 9:27 am

A computational model is a surrogate version of something usually made on a computer. An example that most people are familiar with are the computational models used to predict the weather. If you know how low pressure and high pressure fronts interact, and you know where one is and how fast it is moving, you can program software to play the situation out in a simulation, predicting what will happen and how quickly. […]

If you know how the thalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and cortex all work together, you can simulate how inputs into one structure might influence the others. In this case each brain structure would basically be a ‘black box’ that received input and produced output based on known data.

{ The Cellular Scale | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | May 23rd, 2012 3:22 pm

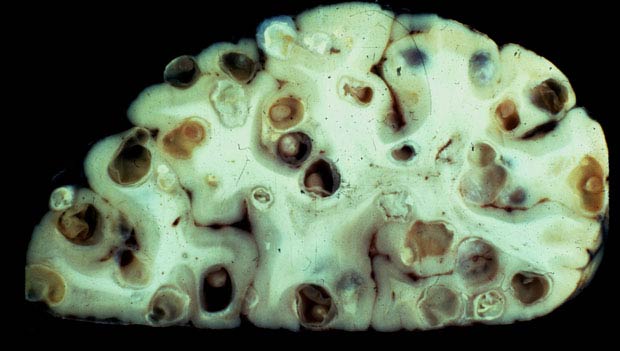

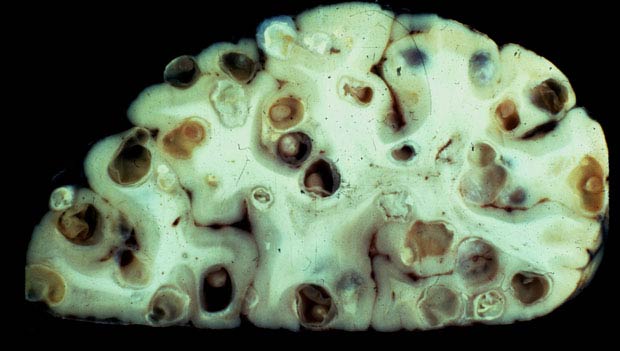

{ A human brain overrun with cysts from Taenia solium, a tapeworm that normally inhabits the muscles of pigs. | Discover | full story }

brain, gross, health | May 19th, 2012 2:00 pm

{ Why do some people enjoy the taste of broccoli while others find it bitter and unpleasant? Why do some seek out spicy and tangy meals on a restaurant’s menu while others stick with the bland and familiar? New research is uncovering the neurobiological and genetic sources of taste preferences, which can influence not just eating habits but also health. | Brain Facts | full story }

brain, food, drinks, restaurants, health, science | May 18th, 2012 1:34 pm

The great innovations come with side-effects. I have encountered people who said this about our chronic back pains being a side-effect of upright walking. It is a great thing but may have a couple of weak spots. We would actually be surprised if evolution didn’t take some time in a shake down of a new species.

A recent paper in Cell by 20 authors has tackled the question of whether autism is the unfortunate result of the malfunctioning of a relatively new aspect of the human brain.

{ Thoughts on thoughts | Continue reading }

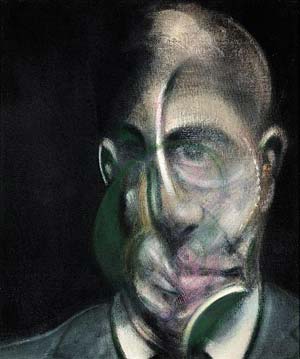

painting { Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976 }

Francis Bacon, brain, theory | May 15th, 2012 5:39 am

Modernity became obsessed with analysis and the elimination of vague, ambiguous, or contradictory ideas. We fell almost completely under its sway and came to imagine that the picture of reality that such thinking provided gave us the best way to understand our world and our place in it.

It was as if we had finally found our way out of the cave and into the kind of light that Plato had thought existed with the Platonic forms. It appeared that modern thinkers had found their way out of the shadowy and mysterious realm of our actual experience and found the kind of certainty that Plato had sought.

Today, however, we are able to see that from a very different perspective because of what we know concerning the human brain. We now know that as appealing as such certainty is, it merely represents one way that the human brain is capable of thinking. Instead of the moving picture of our actual experience, we are capable of ideas that represent snap shots, which make the distances, perspectives, and relations that we actually experience appear fixed and give us the kind of clear and distinct ideas that we crave.

In the seventh book of the Republic, Plato sets forth his famous allegory of the cave. The traditional understanding interpreted it as Plato arguing that both becoming and being were real because there were two different worlds or realms of reality. One was the world of sense-data, which the Pre-Socratic philosopher, Heraclitus argued was purely a matter of becoming. In this world, nothing ever exists in a pure state of being but is always becoming something else.

Plato however, claimed that there was another world where things did exist in a pure state of being. Parmenides and several other Pre-Socratic philosophers had long claimed that the world of which Heraclitus spoke was an illusory world produced by a naïve trust in our unreliable senses and that in fact reason showed us that only being truly existed and all becoming and change was illusory. Plato agreed with both Heraclitus and Parmenides: he believed that the world of our sense data was real and not merely illusory, but there was also a world of pure being - the parallel universe that Plato would come to describe as the world of the forms.

{ The Philosopher | Continue reading }

photo { Steve Schapiro, Samuel Beckett Looking at Parrot, New York, 1964 }

brain, ideas | May 9th, 2012 7:32 am

Poltergeists are defined as paranormal, mischievous ghostly presences that appear to a select group of people. As paranormal entities, they are beyond investigation by rational scientific means. Or are they? Odd sensations, visions, felt presences, out-of-body experiences, etc. have all been explained by unusual brain activity. Hence, neuroscientists should consider that poltergeists exist in the mind of the perceiver, not as a physical reality in the external world.

A new paper by parapsychologist William G. Roll and colleagues reported on the case of a woman who experienced paranormal phenomenon after suffering a head injury. (…)

[After the head injury,] …the relationship with her first husband deteriorated because he insisted she was not the same person. According to her reports one night he tried to kill her. The anomalous phenomena began that night and have been intermittent since that time. Their intensity and frequency have increased during the last 2–3 years.

EEG recordings revealed chronically abnormal activity at a right temporal lobe electrode.

{ The Neurocritic | Continue reading }

brain, incidents, neurosciences, relationships | May 7th, 2012 11:54 am

From what I previously understood, people would ingest mushrooms, and if they were in a negative state of mind, they’d have a “bad trip.” If they were with friends, with other people tripping, they were more likely to have a “good trip.” Aspects of these trips seemed to include lots of visual and auditory hallucinations: “halos” glowing around light sources, warping colors, maybe some synesthesia.

So I just figured that magic mushrooms must hyper-activate the parts of the brain that perceive color and sound, to the point where people perceive things that aren’t even there.

However, recent research out of the U.K. says that, surprisingly, I’ve got it all backwards. (…)

Within a minute or two, the test subjects started to feel the effects of the psilocybin, and the researchers gave them fMRIs during their trips. Surprisingly to me, and to the scientists, brain activity and blood flow decreased by up to 20% during the influence of the drug, and these decreases were proportional to the reported intensity of the trip. (…) The thought behind this finding is that when people do shrooms, pathways in the brain that would normally restrict cognition are temporarily turned off, allowing people to cognate at higher levels than ever before. Some of these same cognition-restraining pathways are overactive in cases of depression, but I won’t go so far as to suggest shrooms as a treatment for depressive disorders.

{ Try Nerdy | Continue reading }

photo { Stefan Heyne }

brain, drugs, neurosciences | May 3rd, 2012 8:13 am

Brain neuroimaging studies continue to outline the structural and functional abnormalities in disorders of mood. A relatively consistent finding has been a reduced volume of the brain hippocampus in major depressive disorder. Studies of hippocampal volume in the less common bipolar disorder have been inconsistent–some studies have found reduced hippocampal volumes while others have not.

The hippocampus is an important brain region to understand in the mood disorders. The hippocampus has a key role in memory. Patients with mood disorders commonly display impairments in mood including deficitis in autobiographical memory. Unipolar depression appears to increase risk for later development of Alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampal volume reduction is a common finding in Alzheimer’s disease. (…)

Lithium is noted to have significant neuroprotective effects. (…) It is possible that bipolar patients treated with lithium may experience less hippocampal atrophy than those not treated with lithium.

{ Brain Posts | Continue reading }

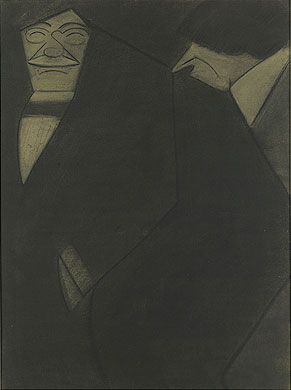

charcoal on paper { Marius de Zayas, John Marin and Alfred Stieglitz, ca. 1912–13 }

brain, memory, neurosciences | May 2nd, 2012 7:25 am

A team led by psychology professor Ian Spence at the University of Toronto reveals that playing an action videogame, even for a relatively short time, causes differences in brain activity and improvements in visual attention. (…) This is the first time research has attributed these differences directly to playing video games.

{ University of Toronto | Continue reading }

brain, leisure, technology | April 26th, 2012 12:01 pm

Universal mind uploading is the concept (…) that the technology of mind uploading will eventually become universally adopted by all who can afford it, similar to the adoption of modern agriculture, hygiene, and permanent dwellings. The concept is rather infrequently discussed, due to a combination of 1) its supposedly speculative nature and 2) its “far future” time frame. Yet some futurists, such as myself, see the eventuality as plausible by as early as 2050. (…)

Mind uploading would involve simulating a human brain in a computer in enough detail that the “simulation” becomes, for all practical purposes, a perfect copy and experiences consciousness, just like protein-based human minds. If functionalism is true, as many cognitive scientists and philosophers believe, then all the features of human consciousness that we know and love — including all our memories, personality, and sexual quirks — would be preserved through the transition. By simultaneously disassembling the protein brain as the computer brain is constructed, only one implementation of the person in question would exist at any one time, eliminating any unnecessary philosophical confusion. Whether the computer upload is “the same person” is up for the person and his/her family and friends to decide. (…)

An upload of you with all your memories and personality intact is no different from you than the person you are today is different than the person you were yesterday when you went to sleep, or the person you were 10-30 seconds ago when quantum fluctuations momentarily destroyed and recreated all the particles in your brain.

{ h+ | Continue reading }

brain, future, ideas | April 19th, 2012 1:33 pm

Natural selection never favors excess; if a lower-cost solution is present, it is selected for. Intelligence is a hugely costly trait. The human brain is responsible for 25 per cent of total glucose use, 20 per cent of oxygen use and 15 per cent of our total cardiac output, although making up only 2 per cent of our total body weight. Explaining the evolution of such a costly trait has been a long-standing goal in evolutionary biology, leading to a rich array of explanatory hypotheses, ranging from evasion of predators to intelligence acting as an adaptation for the evolution of culture. Among the proposed explanations, arguably the most influential has been the “social intelligence hypothesis,” which posits that it is the varied demands of social interactions that have led to advanced intelligence.

{ Proceedings of The Royal Society B | Continue reading }

brain, ideas, science | April 11th, 2012 11:36 am