economics

Here is the great irony: S&P (and the rest of the ratings agencies) helped contribute in no small way to the overall economic crisis. The toadies rated junk securitized mortgage backed paper AAA because they were paid to do so by banks.

They are utterly corrupt, and should have received the corporate death penalty (ala Arthur Anderson).

{ Barry Ritholtz | Continue reading }

related { Standard & Poor’s removed the United States government from its list of risk-free borrowers for the first time since it was granted an AAA rating in 1917. | Standard & Poor’s (S&P) is a United States–based financial-services company, headquartered in Rockefeller Center in New York City. It is a division of the McGraw-Hill Companies. | S&P’s credit ratings }

photo { Scott Eells }

U.S., economics | August 6th, 2011 12:40 pm

Turns out that your name is more influential than you think.

Researchers found that the “speed with which adults acquire items [correlates] to the first letter of their childhood surname.”

This means that when it comes to purchasing goods, people with last names that begin with a letter closer to the end of the alphabet tend to acquire items faster than people with last names that begin with a letter closer to the beginning of the alphabet. They call it the “Last Name Effect,” and hypothesize that it is caused by “childhood ordering structure.”

In their words, “since those late in the alphabet are typically at the end of lines, they compensate by responding quickly to acquisition opportunities.”

{ Why We Reason | Continue reading }

photo { Louis Stettner, Rue des Martyrs, 1951 }

Onomastics, economics, psychology | August 4th, 2011 4:05 pm

Selbee bought $307,000 worth of $2 tickets for a relatively obscure game called Cash WinFall, tying up the machine that spits out the pink tickets for hours at a time. Down the road at Jerry’s Place, a coffee shop in South Deerfield, Selbee’s husband, Gerald, was also spending $307,000 on Cash WinFall. Together, the couple bought more than 300,000 tickets for a game whose biggest prize - about $2 million - has been claimed exactly once in the game’s seven-year history.

But the Selbees, who run a gambling company called GS Investment Strategies, know a secret about the Massachusetts State Lottery: For a few days about every three months, Cash WinFall may be the most reliably lucrative lottery game in the country. Because of a quirk in the rules, when the jackpot reaches roughly $2 million and no one wins, payoffs for smaller prizes swell dramatically, which statisticians say practically assures a profit to anyone who buys at least $100,000 worth of tickets.

{ Boston Globe | Continue reading }

photo { Kate Peters }

economics, scams and heists | August 3rd, 2011 10:00 pm

Economists have long argued that individuals, particularly those in the lower socioeconomic stratum, engage in conspicuous consumption to signal their status in society. Since one’s income, a common marker of status, is not visible to others, individuals can speciously signal their wealth by displaying products that are a surrogate for income, such as luxury watches, expensive cars, and designer clothes. Alternatively, a psychological perspective on this phenomenon suggests that status consumption is driven by a desire to restore various forms of self-worth. For instance, aversive psychological states such as powerlessness and self-threat drive individuals to consume status goods for their compensatory benefits.

We contend that this desire to protect and restore one’s self-worth affects not only what is consumed but also how it is consumed—purchased through credit versus cash. Specifically, the very same psychological force (i.e., threatened self- worth) that compels individuals toward status consumption may also increase individuals’ likelihood of consuming these goods through credit rather than cash.

{ SAGE | Continue reading }

painting { Alex Gross }

economics, psychology | July 29th, 2011 8:17 pm

While the Frenchman credited with inventing dry cleaning started with turpentine, perc has been used since the 1930s to clean clothes, and about 80% of cleaners still rely on it. Like turpentine—and benzene, kerosene and gasoline, which were also tried in the early years—perc is good at dissolving oil-based stains. It is pumped into a supersized washing machine to flush dirt from the clothes.

Stubborn stains from difficult-to-remove substances, such as ink, wine and mustard, are attacked by hand with chemicals that target particular substances. Bruce Barish, owner of New York City’s Ernest Winzer Cleaners, cites balsamic vinaigrette as “very hard to get out.” It’s a mix of both water-based and oily stains with a dark dye that is hard to remove—especially since most customers accidentally rub it in.

The quality and service vary, in part because most dry cleaners are independently owned. There are 24,124 dry-cleaning and non-coin-operated laundry establishments in the U.S., according to the Census Bureau.

In a 2009 study that examined 50 randomly selected dry cleaners, New York-based Floyd Advisory LLC found that women paid an average of 73% more than men for laundered shirts. Dry cleaners surveyed say women’s shirts don’t fit in their industrial presses as well as men’s and must be ironed by hand.

Last year, market-research firm Mintel International found that 75% of women who had gone clothes-shopping in the past 12 months said they avoided buying clothes that required dry cleaning.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

U.S., economics | July 29th, 2011 6:20 pm

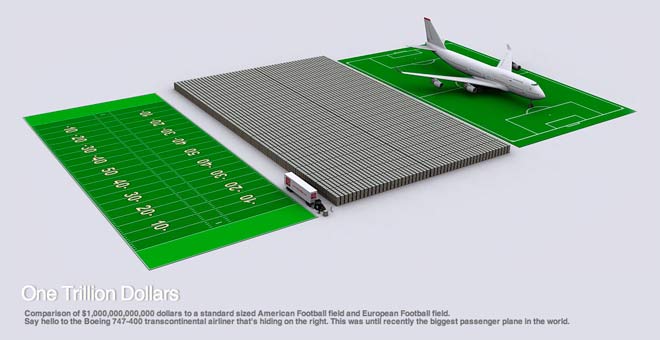

U.S., economics, visual design | July 28th, 2011 6:20 pm

A lot of occupations that didn’t exist years ago: two college graduate daughters, one a web designer for a financial firm, other works with a company that does social media marketing. Didn’t exist when they were born. Proliferation of new occupations.

Harder to be a Renaissance person. It was imaginable 400 years ago that you could read, master a relatively large part of the world’s knowledge. Seen it argued that Leibniz knew just about everything that could be known at that time. Da Vinci superior in many fields. Now a Renaissance person if you are good in a couple of things, if you know something about a lot of things. The cost of mastering a lot of things has gone up. (…) How much could a Newton or Leibniz today master? Not all of it. When we went to graduate school in economics (…) Finance was around, but behavioral economics and experimental economics were not, or were less prominent. I used to call myself a macroeconomist–I can’t follow macroeconomics; sort of can; highly mathematical, Euler equation stuff. (…) Profusion of journals in every discipline. If you want to call yourself a master of any field, not sure that leads to true mastery. (…)

Knowledge is more dispersed. Not just an issue for people trying to become academics. True for somebody in business: if you want to be a CEO, there are many more things you have to understand than you used to. You didn’t have to understand information technology to be a CEO. Didn’t have to be an expert in global supply chain management. Didn’t necessarily have to understand logistics, be as sophisticated in finance.

Even for consumers, amount of knowledge you need is more. More different financial instruments available for you to either trip up on or take advantage of. All sorts of different products and services that didn’t exist. (…) Households are outsourcing more of the food preparation, cleaning, lawn care, more complex forms of electronic communication–have cell phone, do you still keep your land line? Life more complex for everybody. Weird thing. Have computer network in house, access Internet wirelessly; running an IT center. Measurement question: has my house gotten more specialized or less specialized? What am I doing with an IT network in my house? Verizon supplies it; I don’t master much of it other than opening the door to let someone in to drill in my wall. Hard to measure these phenomena. Makes us very much dependent on other people’s expertise.

{ Arnold Kling/EconTalk | Continue reading }

economics, ideas | July 27th, 2011 8:40 pm

In the months after the collapse of the credit market in the fall of 2008, The New York Times was forced to take drastic measures to stay afloat: In January 2009, it granted Mexican telecom mogul Carlos Slim Helú purchase warrants for 15.9 million shares of Times Company stock for the privilege of borrowing $250 million at essentially a junk-bond interest rate of 14 percent. Two months later, in a move redolent with uncomfortable symbolism, the company raised another $225 million through a sale-leaseback deal for its headquarters. Add on double-digit declines in both circulation and ad pages and the trend lines looked increasingly clear: The New York Times was doomed.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the graveyard. Though the Times’ circulation dipped during the crash years, much of the lost revenue was made up for by doubling the newsstand price, from $1 to $2—evidence, the paper insisted, that its premium audience understood the value of a premium product. In March, after several years of planning and tens of millions in investments, the Times launched a digital-subscription plan—and the early signs were good. In fact, less than 48 hours before my interview, the Times announced it would finish paying back the Carlos Slim loan in full on August 15, three and a half years early. When they were released last week, the company’s second-quarter financial results showed an overall loss largely owing to the write-down of some regional papers, but they also contained a much more important piece of data: The digital-subscription plan—the famous “paywall”—was working better than anyone had dared to hope.

{ NY mag | Continue reading }

economics, press | July 27th, 2011 6:00 pm

Dear Investor,

When you only do one thing, you do it well.

Need to send a contract to a client? I will fax it. Want to submit a proposal to a client? I will fax it. Want to send a birthday party invitation to a client? I will fax it.

I Will Fax Anything specializes in the sending and receiving of faxes… and that’s it.

Want to surf the Internet? Find a library. Looking for a ream of paper? Go to Staples. Want to loiter? Go home. I am not your friend.

Last week a man came into the Oak Forest I Will Fax Anything and asked for a small pepperoni pizza and a side of Crazy Bread. I don’t sell pizza. I only charge people for faxing things.

{ Dennis O’Toole | Continue reading }

economics, experience, haha | July 26th, 2011 11:22 am

Illegal markets differ from legal markets in many respects. Although illegal markets have economic significance and are of theoretical importance, they have been largely ignored by economic sociology. In this article we propose a categorization for illegal markets and highlight reasons why certain markets are outlawed. We perform a comprehensive review of the literature to characterize illegal markets along the three coordination problems of value creation, competition, and cooperation. The article concludes by appealing to economic sociology to strengthen research on illegal markets and by suggesting areas for future empirical research. (…)

Markets are arenas of regular voluntary exchange of goods or services for money under conditions of competition (Aspers/Beckert 2008). The exchange of goods or services does not constitute a market when the exchange takes place only very irregularly and when there is no competition either on the demand side or on the supply side. Markets are illegal when either the product itself, the exchange of it, or the way in which it is produced or sold violates legal stipulations. What makes a market illegal is therefore entirely dependent on a legal definition.

When a market is defined as illegal, the state declines the protection of property rights, does not define and enforce standards for product quality, and can prosecute the actors within it. Not every criminal economic activity constitutes an illegal market; the product or service demanded may be too specific for competition to emerge, or it may simply be business fraud. Since illegality is defined by law, what constitutes an illegal market differs between legal jurisdictions and over time.

{ Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies | Continue reading | PDF }

Linguistics, economics, law | July 25th, 2011 9:07 am

In a study published today, the University of Helsinki’s Tatu Westling points out a surprising strong correlation between a country’s GDP growth rate and average penile length. (…)

Countries that averaged smaller penis sizes grew at a faster rate than their larger counterparts between 1960 and 1985. Every centimeter increase in penis size accounted for a 5 to 7 percent reduction in economic growth. The study also showed that overall GDP was at its highest in countries with average-sized penises with GDP falling at the extremes of penis length.

{ The Atlantic Wire | Continue reading }

economics, science | July 22nd, 2011 4:26 pm

The Wall Street Journal says Apple is thinking of making a bid for Hulu and Seattlepi.com says Microsoft’s is no longer interested, which leaves Amazon, Apple, Google, Yahoo, and any unnamed parties. I can’t think of any unnamed parties, by the way, so I’m guessing one of these will walk with Hulu, which went into play a couple weeks ago following an unsolicited (and still unidentified) bid.

Of course the three big network owners of Hulu will guarantee five years of continued program access with the first two years exclusive. That’s because they have no money in Hulu and each stands to walk with $600+ million from the sale, but only if there is a sale. Without such an exclusivity period there will be no sale and no $600+ million. None of these networks can buy out the others for antitrust reasons so the “networks might balk” story is just to sell newspapers (or electrons). Hulu will be sold.

{ Robert X. Cringely | Continue reading }

economics, media, technology | July 22nd, 2011 4:10 pm

Despite persistent urban myths to the contrary, chewing gum is, technically speaking, edible. However, doctors do agree that it is not usually wise to swallow it, due to the risk of “gum-based gastrointestinal blockages.” Given that in 2005, Americans chewed, on average, 160-180 pieces or about 1.8 lbs of gum per person, per year, with relatively few swallowing incidents, the resulting post-masticatory waste probably adds up to more than 250,000 tons annually.

Inevitably, disposing of this sticky mass poses some challenges. (…) Discarded chewing gum debris forms the dominant decoration of the urban floor.

{ Edible Geography | Continue reading }

economics, leisure, pipeline | July 20th, 2011 4:25 pm

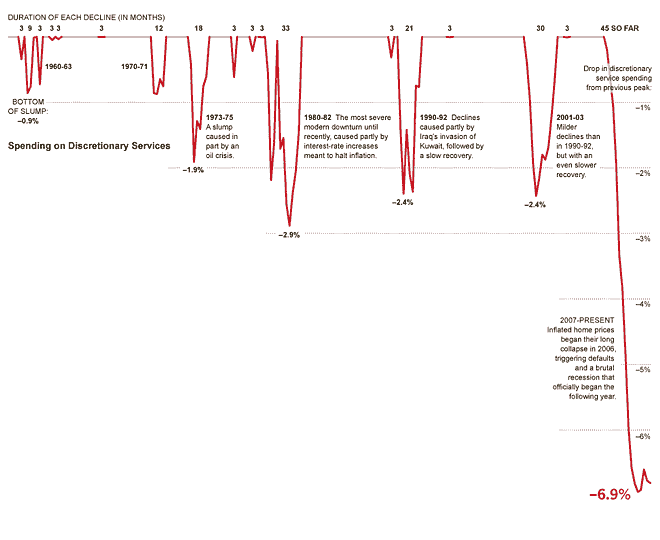

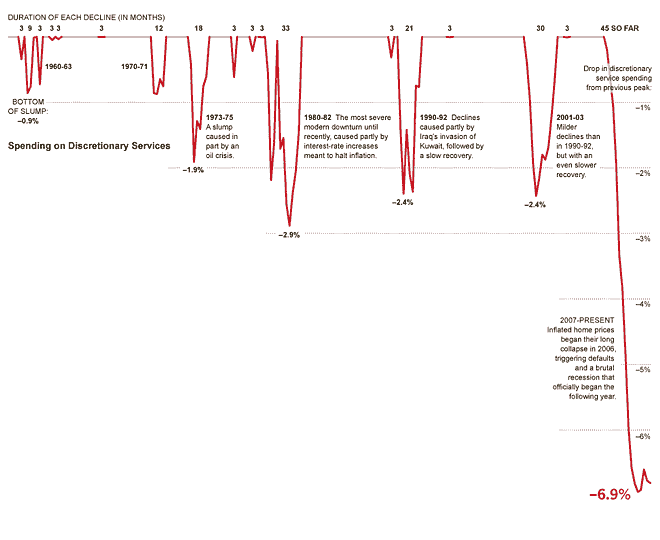

{ During economic downturns, consumers usually spend less on what the Fed calls “discretionary services” — items like education, entertainment, restaurant meals and insurance. But in the chart above, it’s clear that consumers today are cutting back much more sharply. Part of the reason: In previous years, households often added debt to continue spending. Now the bill has come due. | NY Times | full story }

U.S., economics | July 19th, 2011 8:05 pm

U.S., halves-pairs, housing, law | July 19th, 2011 7:45 pm

More than a billion people cannot count on meeting their basic needs for food, sanitation, and clean water. Their children die from simple, preventable diseases. They lack a minimally decent quality of life.

At the same time, more than a billion people live at a hitherto unknown level of affluence. They think nothing of spending more to go out to dinner than the other billion have to live on for a month. Do they therefore have a high quality of life? Being able to meet one’s basic needs for food, water, and reasonable health is a necessary condition for having an adequate quality of life, but not a sufficient one.

In the past, we spent much of our day ensuring we would have enough to eat. Then we would relax and socialize. Now, for the affluent, it is so easy to meet our basic needs that we lack purpose in our daily activities—leading us to consume more, and thus to feel we do not earn enough for all that we “need.”

{ What does quality of life mean? And how should we measure it? Our panel of global experts weighs in. | World Policy Institute | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, within the world | July 19th, 2011 7:28 pm

Times have not been good for electronic media giant Sony. The New York Times recently carried a short article that reported the company has lost 37 percent of its market value over the last six years. It has been hit by one disaster after another. Future projections do not look good either.

While there are many explanations that analysts offer to explain the dismal performance of this once stellar company, there is one explanation that is never mentioned: the Curse of the DaVinci Code.

It has been six years since Sony began production of the movie, The DaVinci Code, based on the bestselling yet now forgotten book with the same title by Dan Brown. The book’s blasphemous affirmations denied the Divinity of Christ and claimed He was married to Saint Mary Magdalene and had children, which offended countless faithful at the time. Numerous books and studies debunked these absurd and horrific theses along with others that author Dan Brown nevertheless affirmed were true.

From the moment production began, it appears as if the Curse of the DaVinci Code descended upon Sony and there it still remains.

{ The American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property | Continue reading }

economics, haha, technology, weirdos | July 19th, 2011 7:15 pm

Here is an obvious truth overlooked by too many: Almost all companies die. They have a theoretically infinite lifespan, but eventually, their day in the sun passes, their parts are sold off for scrap, they fade into the dim dusty pages of history. Sure, Europe has centuries old breweries and specialty foods companies, but they are notable because they are exceptions.

Think back to the original Dow Jones Industrials, filled as it was with Steam and Leather Belt companies, all gone bankrupt nearly a century ago. How many of the original companies in the DJIA are still even in existence?

Microsoft was once technology’s behemoth, the 800 pound gorilla, an unstoppable anti-competitive monopolist. And today? It was a great 20 year run, but it’s mostly over. They still have the cash horde and engineering chops to create a smash hit like the Kinect, and they are a cash cow, but the odds are, their glory days are behind them.

While some companies manage to have a second act — Apple and IBM are notable examples — they too, remain the exception.

Today, tech companies’ lifespans are measured in internet years. Any firms dominance of any given space is likely to cover a much smaller period — way less than a decade in real time. The obvious poster child for this syndrome? MySpace. Even mighty Google is seeing market share growth in search slip as competitors nip at its heels.

All of which leads me to the question of the day: Has Facebook missed its IPO window? (…)

There are signs that Google Plus is a worthy competitor: They quickly amassed 10 million users, and that is while they are in Beta.

{ Barry Ritholtz | Continue reading }

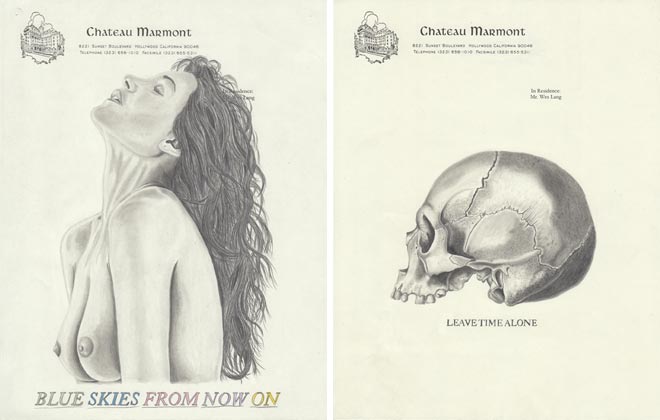

drawings { Wes Lang }

economics, ideas, technology | July 18th, 2011 2:40 pm

Atlanta entrepreneur Mike Mondelli has access to more than a billion records detailing consumers’ personal finances — and there is little they can do about it.

The information collected by his company, L2C, comes from thousands of everyday transactions that many people do not realize are being tracked: auto warranties, cellphone bills and magazine subscriptions. It includes purchases of prepaid cards and visits to payday lenders and rent-to-own furniture stores. It knows whether your checks have cleared and scours public records for mentions of your name.

Pulled together, the data follow the life of your wallet far beyond what exists in the country’s three main credit bureaus. Mondelli sells that information for a profit to lenders, landlords and even health-care providers trying to solve one of the most fundamental questions of personal finance: Who is worthy of credit?

The answer increasingly lies in the “fourth bureau” — companies such as L2C that deal in personal data once deemed unreliable. Although these dossiers cover consumers in all walks of life, they carry particular weight for the estimated 30 million people who live on the margins of the banking system. Yet almost no one realizes these files exist until something goes wrong.

Federal regulations do not always require companies to disclose when they share your financial history or with whom, and there is no way to opt out when they do. No standard exists for what types of data should be included in the fourth bureau or how it should be used. No one is even tracking the accuracy of these reports. That has created a virtually impenetrable system in which consumers, particularly the most vulnerable, have little insight into the forces shaping their financial futures.

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

economics, uh oh | July 18th, 2011 2:20 pm

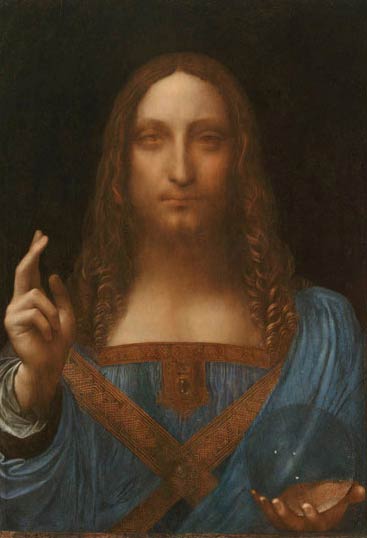

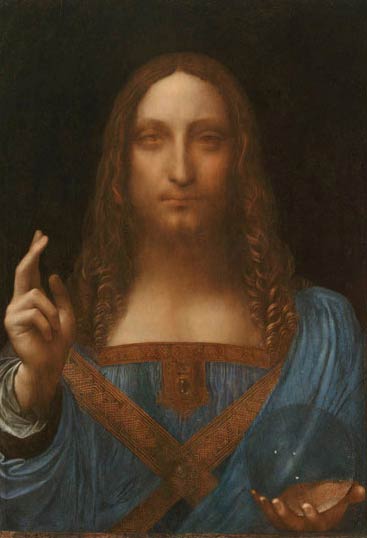

Every few weeks, photographs of old paintings arrive at Martin Kemp’s eighteenth-century house, outside Oxford, England. (…) Kemp scrutinizes each image with a magnifying glass, attempting to determine whether the owners have discovered what they claim to have found: a lost masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci.

Kemp, a leading scholar of Leonardo, also authenticates works of art—a rare, mysterious, and often bitterly contested skill. His opinions carry the weight of history; they can help a painting become part of the world’s cultural heritage and be exhibited in museums for centuries, or cause it to be tossed into the trash. His judgment can also transform a previously worthless object into something worth tens of millions of dollars. (His imprimatur is so valuable that he must guard against con men forging not only a work of art but also his signature.)

{ New Yorker | full story | PDF }

painting { Leonardo’s ‘lost’ Christ, sold for £45 in 1956, now valued at £120m | Guardian | full story }

art, economics | July 15th, 2011 12:40 am