We may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us

Atlanta entrepreneur Mike Mondelli has access to more than a billion records detailing consumers’ personal finances — and there is little they can do about it.

The information collected by his company, L2C, comes from thousands of everyday transactions that many people do not realize are being tracked: auto warranties, cellphone bills and magazine subscriptions. It includes purchases of prepaid cards and visits to payday lenders and rent-to-own furniture stores. It knows whether your checks have cleared and scours public records for mentions of your name.

Pulled together, the data follow the life of your wallet far beyond what exists in the country’s three main credit bureaus. Mondelli sells that information for a profit to lenders, landlords and even health-care providers trying to solve one of the most fundamental questions of personal finance: Who is worthy of credit?

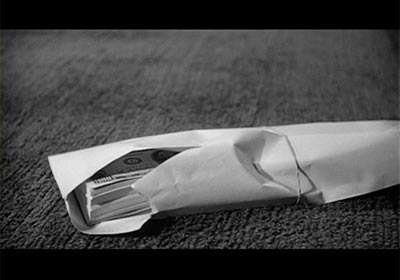

The answer increasingly lies in the “fourth bureau” — companies such as L2C that deal in personal data once deemed unreliable. Although these dossiers cover consumers in all walks of life, they carry particular weight for the estimated 30 million people who live on the margins of the banking system. Yet almost no one realizes these files exist until something goes wrong.

Federal regulations do not always require companies to disclose when they share your financial history or with whom, and there is no way to opt out when they do. No standard exists for what types of data should be included in the fourth bureau or how it should be used. No one is even tracking the accuracy of these reports. That has created a virtually impenetrable system in which consumers, particularly the most vulnerable, have little insight into the forces shaping their financial futures.