De Kooning, vite (la Vue, le texte)

{ via Secret Forts }

Last month, Gawker published a series of messages that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange had once written to a 19-year-old girl he’d become infatuated with. Gawker called the e-mails “creepy,” “lovesick,” and “stalkery.”

(…) What really surprised me was his typography.

When he sits down to type, Julian Assange reverts to an antiquated habit that would not have been out of place in the secretarial pools of the 1950s: He uses two spaces after every period. Which—for the record—is totally, completely, utterly, and inarguably wrong.

Oh, Assange is by no means alone. Two-spacers are everywhere.

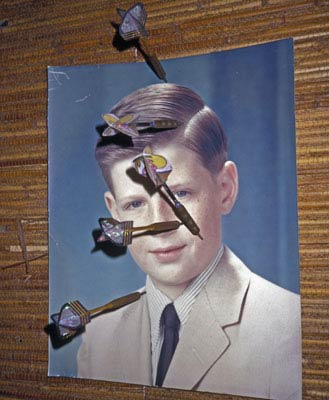

artwork { Karsten Konrad, Black eye, 2010 }

Everyone already knows that romantic love requires sexual attraction, that’s a given. The second component is almost as well known. It’s called attachment, and its part of the show in both romantic and all other kinds of love, including love within families. Attachment is found in other mammal besides us humans: our cats Mischa and Wolfie have become attached to me and my wife, and we are attached to them.

Attachment gives a physical sense of a connection to the beloved. The most obvious cues to attachment are missing the beloved when they are away, and contentment when they return. Loss of that person invokes deep sadness and grief. Another less reliable cue is the sense of having always known a person whom we have just met. This feeling can be intense when it occurs, but it also may be completely absent.

Attachment accounts for an otherwise puzzling aspect of “love”: one can “love” someone that one doesn’t even like. (…)

Finally, there is a third component that is much more complex and subtle than attraction or attachment. It has to do with the lover sharing the thoughts and feelings of the beloved. The lover identifies with the loved person at times, to the point of actually sharing their thoughts their feelings. He or she feels their pain at these times, or joy, or any other feeling, as if it were her or his own. Two people can be attuned, at least at times, to each others’ thoughts and feeling.

It is important to note however, that to qualify as genuine love, the sharing need be balanced between self and other. One shares the others thoughts and feelings as much as one’s own, no more and no less. (…)

The definition of romantic love proposed here involves three components, the three A’s: Attraction, Attachment, and Attunement.

bonus:

Statistics is what people think math is. Statistics is about patterns and that’s what people think math is about. The difference is that in math, you have to get very complicated before you get to interesting patterns. The math that we can all easily do – things like circles and triangles and squares – doesn’t really describe reality that much. Mandelbrot, when he wrote about fractals and talked about the general idea of self-similar processes, made it clear that if you want to describe nature, or social reality, you need very complicated mathematical constructions. The math that we can all understand from high school is just not going to be enough to capture the interesting features of real world patterns. Statistics, however, can capture a lot more patterns at a less technical level, because statistics, unlike mathematics, is all about uncertainty and variation. (…)

Bill James once said that you can lie in statistics just like you can lie in English or French or any other language. Sure, the more powerful a language is the more ways you can lie using it. There are a bunch of great quotes about statistics. There’s another one, sometimes attributed to Mark Twain: ‘It ain’t what you don’t know that hurts you, it’s what you don’t know you don’t know.’

photo { Flemming Ove Bech }

The Web hasn’t been designed to do anything. And so it doesn’t do anything, much less anything smart, creative, or suggesting awareness.

Twenty years ago one would have expected something like the Web to have liberated the creative spirits inside tremendous numbers of people who had not previously had such an outlet. Instead, Lanier argues, the Web has caused the evolution of creativity to stagnate.

Where, Lanier asks, are the radically new musical genres since the 1990s? Technological change seems to be accelerating, and yet the development of novel forms of musical expression appears to have not merely slowed, but stalled altogether. We’re listening to non-radical variations on themes that existed two decades ago, Lanier argues. (…)

More generally, he challenges readers to point to the new generation of people living off their creativity on the Web. (…)

Contrary to the prevailing idea that consumers on the Web should not be obligated to pay individual human content-creators for their work, Lanier is adamant that music and human-created information should not be free. Creativity that goes unpaid leads to a novelty- and diversity-impoverished intellectual world dominated by material that takes minimal effort to produce—think LOLcats.

The experience of pleasure is the result of mechanisms designed to bring about (outcomes that would have led to) fitness gains. When Jared Diamond asked Why is Sex Fun, the answer had to do with the fact that evolved motivational systems are designed to drive organisms to do fitness-enhancing things, like having sex.

Now, I want to emphasize that this is speculative, but it seems to me that a key piece here is that humans seem to benefit from discovering certain kinds of new information they didn’t previously know. One way we do this is to read blogs like this one, but there are any number of other ways. The pleasure we take in new information depends on a number of factors, perhaps including how hard it is to get (easier is generally better), how many other people might be able to get it easily (fewer is often better, which cuts against the previous factor), the value of the information, how confident we are that it’s true, and so on. Gossip and Wikileaks are both, in a sense, satisfying our evolved appetites for finding out secrets, previously unknown and possibly useful information.

Shadow banking—the intricate web of financial arrangements and techniques that developed symbiotically with the traditional, regulated banking system over the past 30 or so years—is territory Gorton has studied for decades, but it (and he) have been largely on the periphery of mainstream economics and policy.

That all changed in mid-2007, when panic broke out in the subprime mortgage market and financial institutions that support it. Expressions like “collateralized debt obligation” and “repo haircut” escaped the confines of Wall Street and business schools, and began to fill the airwaves. We’re still struggling to come to terms—and few are in a better position to help than Gorton.

Gary Gorton: The term shadow banking has acquired a pejorative connotation, and I’m not sure that’s really deserved. So let me provide some context for banking in general.

Banking evolves, and it evolves because the economy changes. There’s innovation and growth, and shadow banking is only the latest natural development of banking. It happened over a 30-year period. It’s part of a number of other changes in the economy. And let me give even a little more context, historical context. I want to convince you that shadow banking is not a new phenomenon, in a sense—that we have had previous “shadow banking” systems in the past—and that there is an important structure to bank debt that makes it vulnerable to panic. So, the crisis is not a special, one-time event, but something that has been repeated throughout U.S. history.

Before the Civil War, banking involved issuing private money—that is, banks issued their own currency or bank notes. And this system worked in the way economists would expect it to work. The private bank money did not trade at par when it circulated any significant distance from the issuing bank. Instead, it was subject to a discount, so that a bank note issued by a New Haven bank as a $10 note might only be worth $9.50 at a store in New York City, for example.

Such discounts from par reflected the risk that the issuing bank might not have the $10—redeemable in gold or silver coins—by the time the holder took the note back to New Haven from New York. The discounts from par were established in local markets. But you can see the problem of trying to buy your lunch when the cook has to figure out the discount. It was simply hard to buy and sell things in such a world.

A big innovation in that period was to back the money by collateral, by state bonds. It turned out that this didn’t always work very well because the bonds themselves were risky. The National Banking Act then corrects this by having the government take over money and issue greenbacks, or federal government notes backed by Treasuries. That was the first time in American history that money traded at par. That was 1863.

The National Banking Acts (there were two of them) are arguably the most important legislation in the financial sector in U.S. history. But what’s interesting, and the reason I bring this up, is that as that was going on, a shadow banking sector was developing. And this shadow banking sector first really makes itself felt in the Panic of 1857 when depositors run and demand currency from their checking accounts.

So, after the Civil War, there’s no problem with currency [because greenbacks were backed by the federal government], but we have this other form of bank money: checking accounts—which appears to be shadow banking.

It develops into something very large and repeatedly has crises. In the late 19th century, academics were literally writing articles with titles like “Are Checks Money?” in top economics journals. And in 1910, the National Monetary Commission, which is the precursor to the Federal Reserve System, commissions 30-some books, one of which is about the extent to which checks are used as currency for transactions. So they’re still studying it in 1910.

Eventually, as you know, we get deposit insurance, which then makes checks safe, so to speak. (…)

In the last 30 or 40 years, there have been a number of fundamental changes in our economy. One of the most fundamental of these has been the rise of institutional investing. The amount of money under management of institutional investors has just been exponentially increasing. These include pension funds, mutual funds, large money managers. And these institutions basically have a need for a checking account, if you will. So if you’re a large institutional money manager, you may need a place to put $200 million, and you want it to earn interest and to be safe and accessible. That led to the metamorphosis of a very old security: the sale and repurchase (or “repo”) market. Like a check, repo had been around for perhaps 100 years, but it was never very large.

{ Interview with Gary Gorton | The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis | Continue reading }

Recent psychological research suggests that people from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic societies — WEIRD, for short — not only live differently from the vast majority of the world’s population, but think differently too.

The unsettling realization for psychologists — the vast majority of whom are WEIRD themselves — is that they don’t actually know much about how the rest of the world thinks. A recent study by Joseph Henrich, Steven Heine, and Ara Norenzayan at the University of British Columbia notes that in the top international journals in six fields of psychology from 2003 to 2007, 68 percent of subjects came from the United States — and a whopping 96 percent from Western, industrialized countries. In one journal, 67 percent of American subjects and 80 percent of non-American subjects were undergraduates in psychology courses.

Does this really matter? Aren’t we all the same, after all? Not really, it turns out. WEIRDos tend to be more individualistic and more competitive than people from non-industrialized Asian and African societies. In tests measuring how groups of people work together, Westerners — and Americans in particular — are far more likely to look out for themselves. They even perceive space differently. When viewing the classic Müller-Lyer illusion (>–< vs. <-->), Americans are far more often and more easily fooled than Africans, possibly as a consequence of living in a world of concrete square angles rather than natural shapes.

No one in the naming world has generated more envy than a boutique firm called Lexicon. You may not recognize the name. But Lexicon has created 15 billion-dollar brand names, including BlackBerry, Dasani, Febreze, OnStar, Pentium, Scion, and Swiffer.

Lexicon’s steady success shows that great names do not come from lightning-bolt moments. (Nobody gets struck 15 times.) Rather, Lexicon’s magic is its creative process.

Consider its recent work for Colgate, which was preparing to launch a disposable mini toothbrush. The center of the brush holds a dab of special toothpaste, which is designed to make rinsing unnecessary. So you can carry the toothbrush with you, use it in a cab or an airplane lavatory, and then toss it out.

Lexicon founder and CEO David Placek’s first insight came early. When you first see the toothbrush, Placek says, what stands out is its small size. “You’d be tempted to start thinking about names that highlight the size, like Petite Brush or Porta-Brush,” he says. As his team began to use the brush, what struck them was how unnatural it was, at first, not to spit out the toothpaste. But this new brush doesn’t create a big mass of minty lather — the mouthfeel is lighter and more pleasant, more like a breath strip. So it dawned on them that the name of the brush should not signal smallness. It should signal lightness, softness, gentleness.

Armed with that insight, Placek asked his network of linguists — 70 of them in 50 countries — to start brainstorming about metaphors, sounds, and word parts that connote lightness. Meanwhile, he asked another two colleagues within Lexicon to help. But he kept these two in the dark about the client and the product. Instead, he gave this team — let’s call them the excursion team — a fictional mission. He told them that the cosmetics brand Olay wanted to introduce a line of oral-care products and it was their job to help it brainstorm about product ideas.

Placek chose Olay because he believed that beauty was an implicit selling point for the new brush. “Good oral care means white teeth, and white teeth are better looking,” Placek says. So the excursion team began to come up with intriguing ideas. For instance, they proposed an Olay Sparkling Rinse, a mouthwash that would make your teeth gleam.

In the end, it was the insight about lightness, rather than beauty, that prevailed. The team of linguists produced a long list of possible words and phrases, and when Placek reviewed it, a word jumped out at him: wisp. It was the perfect association for the new brushing experience and it tested well; it’s not something heavy and foamy, it’s barely there. It’s a wisp. Thus was born the Colgate Wisp.

Notice what’s missing from the Lexicon process: the part when everyone sits around a conference table, staring at the toothbrush and brainstorming names together. (”Hey, how about ToofBrutch — the URL is available!”) Instead, Lexicon’s leaders often create three teams of two, with each group pursuing a different angle.

Last week scientists at Harvard medical school reversed the ageing process in elderly mice. Please don’t get excited, unless you’re a mouse that is. The application to humans is a long way off and even if it will one day be possible, there are many issues attendant on a population that has the means to live forever. (…)

Medical intervention once seemed limited to curing us of diseases that kill. In my childhood, diphtheria and scarlet fever still carried people off, I had friends crippled by polio and aunts deformed by rickets. All this seemed the proper field for medical intervention.

We all know what happened next, a great swathe of advances in hygiene and medicine drove the major killers on to the back foot. From a combination of better lifestyle, cleaner cities and the benefits of a free health service, people began living longer.

We hear regularly of the latest treatments for coronary heart disease, breast cancer, kidney failure, and we live in the belief that when we have an unwelcome diagnosis the full force of medical knowledge will be marshalled for our benefit. We have come to expect better. Now we want life to go on forever. (…)

While most of us don’t want to live forever, many of us would enjoy living longer. At the same time we would like the planet to survive as we know it. There is a contradiction in contemplating a world where everyone lives much longer and where the planet’s resources are finite.

Unless we can learn to eat sand we should bear in mind the fates of places like Angkor Wat and Easter Island, places once dense with people and culture now empty ruins.

Remember that billion heartbeat limit that seems to confine all mammals, from shrews to giraffes? It’s a pretty neat correlation, until you ponder the chief exception: Us.

Most mammals our size and weight are already fading away by age twenty or so, when humans are just hitting their stride. By eighty, we’ve had about three billion heartbeats! That’s quite a bonus.

How did we get so lucky?

Biologists figure that our evolving ancestors needed drastically extended lifespans, because humans came to rely on learning rather than instinct to create sophisticated, tool-using societies. That meant children needed a long time to develop. A mere two decades weren’t long enough for a man or woman to amass the knowledge needed for complex culture, let alone pass that wisdom on to new generations. (In fact, chimps and other apes share some of this lifespan bonus, getting about half as many extra heartbeats.)

So evolution rewarded those who found ways to slow the aging process. Almost any trick would have been enlisted, including all the chemical effects that researchers have recently stimulated in mice, through caloric restriction. In other words, we’ve probably already incorporated all the easy stuff! We’re the mammalian Methuselahs and little more will be achieved by asceticism or other drastic life-style adjustments. Good diet and exercise will help you get your eighty years. But to gain a whole lot more lifespan, we’re going to have to get technical.

So what about intervention and repair?

Are your organs failing? Grow new ones, using a culture of your own cells!

Are your arteries clogged? Send tiny nano-robots coursing through your bloodstream, scouring away plaque! Use tuned masers to break the excess intercell linkages that make flesh less flexible over time.

Install little chemical factories to synthesize and secrete the chemicals that your own glands no longer adequately produce. Brace brittle bones with ceramic coatings, stronger than the real thing!

In fact, we are already doing many of these things, in early-primitive versions. So there is no argument over whether such techniques will appear in coming decades, only how far they will take us.

Might enough breakthroughs coalesce at the same time to let us routinely offer everybody triple-digit spans of vigorous health? Or will these complicated interventions only add more digits to the cost of medical care, while struggling vainly against the same age-barrier in a frustrating war of diminishing returns?

I’m sure it will seem that way for the first few decades of the next century… until, perhaps, everything comes together in a rush.

If that happens — if we suddenly find ourselves able to fix old age — there will surely be countless unforeseen consequences… and one outcome that’s absolutely predictable: We’ll start taking that miracle for granted, too.

On the other hand, it may not work as planned. Many scientists suggest that attempts at intervention and repair will ultimately prove futile, because senescence and death are integral parts of our genetic nature. (…)

So far, our sole hope for such a voyage to the far-off future — and a slim one, at that — is something called cryonics, the practice of freezing a terminal patient’s body, after he or she has been declared legally dead. Some of those who sign up for this service take the cheap route of having only their heads prepared and stored in liquid nitrogen, under the assumption that folks in the Thirtieth Century will simply grow fresh bodies on demand. Their logic is expressed with chilling rationality. “The real essence of who I am is the software contained in my brain. My old body — the hardware — is just meat.” (…)

According to some techno-transcendentalists, “growing new bodies” will seem like child’s play in the future. (..)

All right, what if one of them finally works? All too often, we find that solving one problem only leads to others, sometimes even more vexing.

A number of eminent writers like Robert Heinlein, Greg Bear, Kim Stanley Robinson and Gregory Benford have speculated on possible consequences, should Mister G. Reaper ever be forced to hang up his scythe and seek other employment. For example, if the Death Barrier comes crashing down, will we be able to keep shoehorning new humans into a world already crowded with earlier generations? Or else, as envisioned by author John Varley, might such a breakthrough demand draconian population-control measures, limiting each person to one direct heir per lifespan?

{ David Brin | Continue reading }

I think we have a 50% chance of achieving medicine capable of getting people to 200 in the decade 2030-2040. Presuming we do indeed do that, the actual achievement of 200 will probably be in the decade 2140-2150 - it will be someone who was about 85-90 at the time that the relevant therapies were developed.

There will be no one technological breakthrough that achieves this. It will be achieved by a combination of regenerative therapies that repair all the different molecular and cellular degenerative components of aging.

{ When Will Life Expectancy Reach 200 Years? Aubrey de Grey and David Brin Disagree in Interview }

To see how far back the immortality fantasy goes, read about Gilgamesh, or the Chinese First Emperor who drank mercury in order to live forever — and died in his forties.

{ David Brin/IEET | Continue reading }

Let’s say you transfer your mind into a computer—not all at once but gradually…

Myth number one is that economics is a science. It goes back quite a way. Economists, at least since Marshall, have mistakenly sought to dignify their calling by describing it as a science, and increasingly chosen to add verisimilitude to this pretence by clothing their propositions in the language of science, that is to say, mathematics. But economics is not a science. On scientific matters we rightly expect a high degree of certainty, and are ready to leave many important decisions to properly educated experts. By contrast, economic policy is more like foreign policy than it is like science, consisting as it does in seeking a rational course of action in a world of endemic uncertainty.

{ Five Myths and a Menace | Standpoint magazine | Continue reading }

photo { Stephen Shore }

One of psychology’s most respected journals has agreed to publish a paper presenting what its author describes as strong evidence for extrasensory perception, the ability to sense future events.

The decision may delight believers in so-called paranormal events, but it is already mortifying scientists. Advance copies of the paper, to be published this year in The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, have circulated widely among psychological researchers in recent weeks and have generated a mixture of amusement and scorn.

The paper describes nine unusual lab experiments performed over the past decade by its author, Daryl J. Bem, an emeritus professor at Cornell, testing the ability of college students to accurately sense random events, like whether a computer program will flash a photograph on the left or right side of its screen. The studies include more than 1,000 subjects.

Some scientists say the report deserves to be published, in the name of open inquiry; others insist that its acceptance only accentuates fundamental flaws in the evaluation and peer review of research in the social sciences.

The editor of the journal, Charles Judd, a psychologist at the University of Colorado, said the paper went through the journal’s regular review process. “Four reviewers made comments on the manuscript,” he said, “and these are very trusted people.”

All four decided that the paper met the journal’s editorial standards, Dr. Judd added, even though “there was no mechanism by which we could understand the results.”

But many experts say that is precisely the problem. Claims that defy almost every law of science are by definition extraordinary and thus require extraordinary evidence. Neglecting to take this into account — as conventional social science analyses do — makes many findings look far more significant than they really are, these experts say. (…)

For more than a century, researchers have conducted hundreds of tests to detect ESP, telekinesis and other such things, and when such studies have surfaced, skeptics have been quick to shoot holes in them.

But in another way, Dr. Bem is far from typical. He is widely respected for his clear, original thinking in social psychology, and some people familiar with the case say his reputation may have played a role in the paper’s acceptance. (…)

In one experiment, Dr. Bem had subjects choose which of two curtains on a computer screen hid a photograph; the other curtain hid nothing but a blank screen.

A software program randomly posted a picture behind one curtain or the other — but only after the participant made a choice. Still, the participants beat chance, by 53 percent to 50 percent, at least when the photos being posted were erotic ones. They did not do better than chance on negative or neutral photos.

“What I showed was that unselected subjects could sense the erotic photos,” Dr. Bem said, “but my guess is that if you use more talented people, who are better at this, they could find any of the photos.”

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

There’s a good chance you’ve heard about a forthcoming article in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (JPSP) purporting to provide strong evidence for the existence of some ESP-like phenomenon. (…)

The controversy isn’t over whether or not ESP exists, mind you; scientists haven’t lost their collective senses, and most of us still take it as self-evident that college students just can’t peer into the future and determine where as-yet-unrevealed porn is going to soon be hidden (as handy as that ability might be). The real question on many people’s minds is: what went wrong? If there’s obviously no such thing as ESP, how could a leading social psychologist publish an article containing a seemingly huge amount of evidence in favor of ESP in the leading social psychology journal, after being peer reviewed by four other psychologists? (…)

Having read the paper pretty closely twice, I really don’t think there’s any single overwhelming flaw in Bem’s paper (actually, in many ways, it’s a nice paper). Instead, there are a lot of little problems that collectively add up to produce a conclusion you just can’t really trust.

Below is a decidedly non-exhaustive list of some of these problems. I’ll warn you now that, unless you care about methodological minutiae, you’ll probably find this very boring reading. But that’s kind of the point: attending to this stuff is so boring that we tend not to do it, with potentially serious consequences.

The thing makes a full circle with 20 years inside of it. Amazing, isn’t it? And what wonderful years and sad ending ones. I am back in the little house. It hasn’t changed and I wonder how much I have. For two days I have been cutting the lower limbs off the pine trees to let some light into the garden so that I can raise some flowers. Lots of red geraniums and fuchsias. The fireplace still burns. I will be painting the house for a long time I guess. And all of it seems good.

There are moments of panic but those are natural I suppose. And then sometimes it seems to me that nothing whatever has happened. As though it was the time even before Carol. Tonight the damp fog is down and you can feel it on your face. I can hear the bell buoy off the point. The only proof of course will be whether I can work — whether there is any life in me.

{ John Steinbeck, letters | This Recording | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

photo { Tony Stamolis }

The art world told us that anything could be art, so long as an artist said it was. Almost anyone who goes through a gallery door is likely to have heard about Duchamp and his urinal. The art world is less good at explaining how certain people get to be artists and decide what art is for the rest of us. This process of selection might not make aesthetic or philosophical sense, but it works anyway. It’s about power: whoever holds it gets to officiate and decide. The “art world” is a way of conserving, controlling and assigning this precious resource.

Life is not a long slow decline from sunlit uplands towards the valley of death. It is, rather, a U-bend.

When people start out on adult life, they are, on average, pretty cheerful. Things go downhill from youth to middle age until they reach a nadir commonly known as the mid-life crisis. So far, so familiar. The surprising part happens after that. Although as people move towards old age they lose things they treasure—vitality, mental sharpness and looks—they also gain what people spend their lives pursuing: happiness.

This curious finding has emerged from a new branch of economics that seeks a more satisfactory measure than money of human well-being. Conventional economics uses money as a proxy for utility—the dismal way in which the discipline talks about happiness. But some economists, unconvinced that there is a direct relationship between money and well-being, have decided to go to the nub of the matter and measure happiness itself.

photo { The Haven of Contentment }

The most famous Einstein pronouncement on God came in the form of a telegram, in which he was asked to answer the question in 50 words or less. He did it in 32: “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.”

The leg-to-body ratio (LBR) is a morphological index that has been shown to influence a person’s attractiveness. In our research, 3,103 participants from 27 nations rated the physical attractiveness of seven male and seven female silhouettes varying in LBR. We found that male and female silhouettes with short and excessively long legs were perceived as less attractive across all nations. Hence, the LBR may significantly influence perceptions of physical attractiveness across nations.

{ James Joyce }

Although fiction treats themes of psychological importance, it has been excluded from psychology because it is seen as flawed empirical method. But fiction is not empirical truth. It is simulation that runs on minds of readers just as computer simulations run on computers. In any simulation coherence truths have priority over correspondences. Moreover, in the simulations of fiction, personal truths can be explored that allow readers to experience emotions — their own emotions — and understand aspects of them that are obscure, in relation to contexts in which the emotions arise.

{ Fiction as Cognitive and Emotional Simulation by Keith Oatley | Continue reading }

images { 1. Pinocchio | 2. Maurizio Cattelan, Daddy Daddy, 2008 | 3 }

Bryan Caplan complains about evo psych folk who say we didn’t inherit “an overwhelming, conscious desire to have children,” and about my suggestion that “It is hard to tell grand hero stories” about high fertility.

photo { Richard Foulser }