ideas

Most of us would agree that King Tut and the other mummified ancient Egyptians are dead, and that you and I are alive. Somewhere in between these two states lies the moment of death. But where is that? The old standby — and not such a bad standard — is the stopping of the heart. But the stopping of a heart is anything but irreversible. We’ve seen hearts start up again on their own inside the body, outside the body, even in someone else’s body. Christian Barnard was the first to show us that a heart could stop in one body and be fired up in another. Due to the mountain of evidence to the contrary, it is comical to consider that “brain death” marks the moment of legal death in all fifty states. (…)

Sorensen says that the idea of “irreversibility” makes the determination of death problematic. What was irreversible, say, twenty years ago, may be routinely reversible today. He cites the example of strokes. Brain damage from stroke that was irreversible and led irrevocably to death in the 1940s was reversible in the 1980s. In 1996 the FDA approved tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a clot-dissolving agent, for use against stroke. This drug has increased the reversibility of a stroke from an hour after symptoms begin to three hours.

In other words, prior to 1996, MRIs of the brains of stroke victims an hour after the onset of symptoms were putative photographs of the moment of death, or at least brain death. Today those images are meaningless.

{ Salon | Continue reading }

health, ideas | March 20th, 2012 12:09 pm

You’re famous for denying that propositions have to be either true or false (and not both or neither) but before we get to that, can you start by saying how you became a philosopher?

Well, I was trained as a mathematician. I wrote my doctorate on (classical) mathematical logic. So my introduction into philosophy was via logic and the philosophy of mathematics. But I suppose that I’ve always had an interest in philosophical matters. I was brought up as a Christian (not that I am one now). And even before I went to university I was interested in the philosophy of religion – though I had no idea that that was what it was called. Anyway, by the time I had finished my doctorate, I knew that philosophy was more fun than mathematics, and I was very fortunate to get a job in a philosophy department (at the University of St Andrews), teaching – of all things – the philosophy of science. In those days, I knew virtually nothing about philosophy and its history. So I have spent most of my academic life educating myself – usually by teaching things I knew nothing about; it’s a good way to learn! Knowing very little about the subject has, I think, been an advantage, though. I have been able to explore without many preconceptions. And I have felt free to engage with anything in philosophy that struck me as interesting.

{ Graham Priest interviewed by Richard Marshal | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Whitman }

ideas | March 19th, 2012 3:04 pm

Several theories claim that dreaming is a random by-product of REM sleep physiology and that it does not serve any natural function.

Phenomenal dream content, however, is not as disorganized as such views imply. The form and content of dreams is not random but organized and selective: during dreaming, the brain constructs a complex model of the world in which certain types of elements, when compared to waking life, are underrepresented whereas others are over represented. Furthermore, dream content is consistently and powerfully modulated by certain types of waking experiences.

On the basis of this evidence, I put forward the hypothesis that the biological function of dreaming is to simulate threatening events, and to rehearse threat perception and threat avoidance.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we need to consider the original evolutionary context of dreaming and the possible traces it has left in the dream content of the present human population. In the ancestral environment, human life was short and full of threats. Any behavioral advantage in dealing with highly dangerous events would have increased the probability of reproductive success. A dream-production mechanism that tends to select threatening waking events and simulate them over and over again in various combinations would have been valuable for the development and maintenance of threat-avoidance skills.

Empirical evidence from normative dream content, children’s dreams, recurrent dreams, nightmares, post traumatic dreams, and the dreams of hunter-gatherers indicates that our dream-production mechanisms are in fact specialized in the simulation of threatening events, and thus provides support to the threat simulation hypothesis of the

{ Antti Revonsuo/Behavioral and Bain Sciences | PDF }

archives, psychology, science, theory | March 19th, 2012 3:02 pm

We have all had arguments. Occasionally these reach an agreed upon conclusion but usually the parties involved either agree to disagree or end up thinking the other party hopelessly stupid, ignorant or irrationally stubborn. Very rarely do people consider the possibility that it is they who are ignorant, stupid, irrational or stubborn even when they have good reason to believe that the other party is at least as intelligent or educated as themselves.

Sometimes the argument was about something factual where the facts could be easily checked e.g. who won a certain football match in 1966.

Sometimes the facts aren’t so easily checked because they are difficult to understand but the problem is clear and objective. (…)

Sometimes the facts aren’t as mathematical or logical as the Monty Hall solution. Each party to the argument appeals to ‘facts’ which the other party disputes. (…)

Sometimes the arguments boil down to differences in values. For example, what tastes better chocolate or vanilla ice cream, or who is prettier Jane or Mary? In these cases there isn’t really a correct answer – even when a large majority favors a particular alternative. Values also have a strong way of influencing what people accept as evidence or indeed what they perceive at all.

The interesting thing is that when the disagreement isn’t a pure values difference it should always be possible to reach agreement.

{ Garth Zietsman | Continue reading }

controversy, ideas, relationships | March 19th, 2012 12:13 pm

New support for the value of fiction is arriving from an unexpected quarter: neuroscience.

Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters. Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life.

Researchers have long known that the “classical” language regions, like Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, are involved in how the brain interprets written words. What scientists have come to realize in the last few years is that narratives activate many other parts of our brains as well, suggesting why the experience of reading can feel so alive. Words like “lavender,” “cinnamon” and “soap,” for example, elicit a response not only from the language-processing areas of our brains, but also those devoted to dealing with smells. (…)

Researchers have discovered that words describing motion also stimulate regions of the brain distinct from language-processing areas. (…)

The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life; in each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated. (…) Fiction — with its redolent details, imaginative metaphors and attentive descriptions of people and their actions — offers an especially rich replica. Indeed, in one respect novels go beyond simulating reality to give readers an experience unavailable off the page: the opportunity to enter fully into other people’s thoughts and feelings. (…) Scientists call this capacity of the brain to construct a map of other people’s intentions “theory of mind.” Narratives offer a unique opportunity to engage this capacity, as we identify with characters’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers. (…)

Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined.

{ NYT | Continue reading }

books, neurosciences, psychology | March 19th, 2012 12:10 pm

Wallace had been taking Nardil for his depression since 1989. Nardil is a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, or MAOI, a member of the earliest generation of antidepressants; newer drugs are usually not only more effective against the illness but also less likely to cause collateral damage. In 2007 Wallace was a happy man, writing, married since 2004, for the first time, to the artist Karen Green, and teaching at Pomona College, one of the distinguished Claremont Colleges, where he had an endowed professorial chair that gave him pretty much free rein. After dinner at a Persian restaurant in Claremont one evening, he developed excruciating stomach pains that lasted several days. His doctor suspected a dire food interaction with Nardil, and suggested Wallace go off that outdated medication and try something newer. Wallace had already suspected for several months that Nardil was impeding the flow of The Pale King—though it evidently had not interfered with Infinite Jest—so the idea sounded promising. But then Wallace tried doing without any medication at all, and he landed in the hospital in the fall of 2007. After that he went on one drug after another but never really gave any of them the chance to be effective. Not wanting to foul his home, he tried suicide by overdose in a nearby motel, but survived. A course of twelve electroconvulsive treatments failed to work. He went back on Nardil; it did not kick in quickly enough. Not caring any more what he fouled, on September 12, 2008, he waited for his wife to leave for her gallery, wrote her a two-page note, and hanged himself on the patio of their Claremont home. He left a neat stack of manuscript pages in his garage office for his wife to find.

{ The Claremont Institute | Continue reading }

drugs, experience, ideas | March 18th, 2012 12:00 pm

The treatment of addiction and dependence on, and misuse of, alcohol and other drugs is one of the largest unmet needs in medicine today, so the development of new treatments is a pressing need. However, we have seen the development and use of different terminologies for different drug addictions, which confuses prescribers, users and regulators alike. Here we try to clarify terminology of treatment models based on the pharmacology of treatment agents. This editorial covers all drugs that are used for their pleasurable effects and which therefore can lead to harmful/hazardous use, dependence and addiction. These include nicotine, alcohol and abused prescription drugs such as benzodiazepines, as well as opioids and stimulants.

{ SAGE | Continue reading }

Linguistics, drugs, health | March 16th, 2012 4:10 pm

It is well known that in theory and in reality people cooperate more when then expect to interact over more repetitions, and when they care more about the future.

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

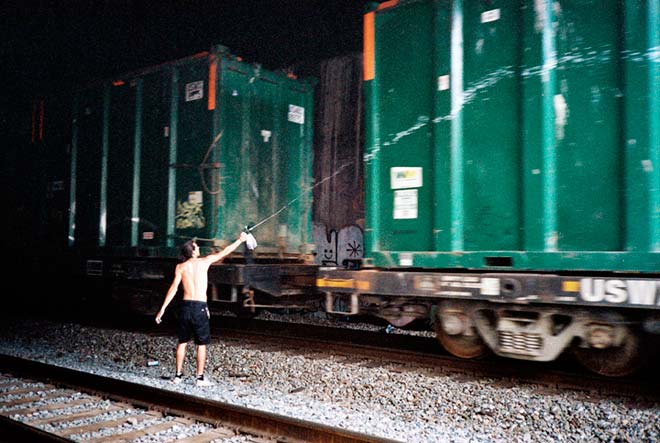

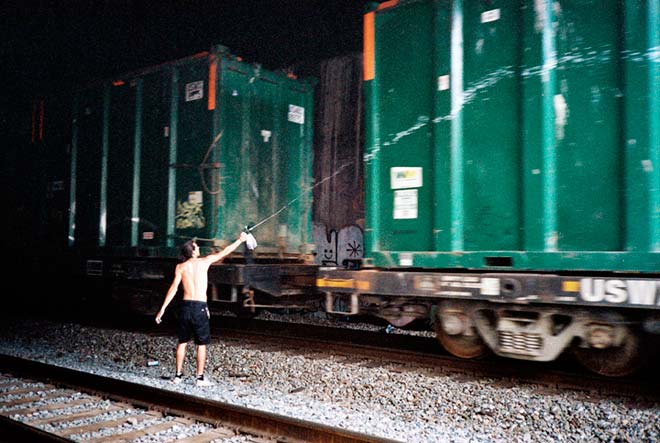

unrelated { Self-Piercing at Thailand Vegetarian Festival }

ideas, relationships | March 16th, 2012 3:39 pm

photo { Emma Hardy }

ideas, photogs | March 15th, 2012 8:11 am

Research has demonstrated that the most popular and most trusted US news network may actually leave viewers both less informed and even more misinformed than people who watch no TV news at all.

{ Neurobonkers | Continue reading }

ideas, media | March 15th, 2012 8:00 am

Some activists and theorists in the field of gender and sexuality have partly or wholly abandoned the designation LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) and instead write and organise under the banner of “queer.” Queer theory and politics originated in the 1990s and continue to be influential today. Many books are written from this perspective, and they inform university courses—Leeds University, for example, offers an MA in Gender, Sexuality and Queer Theory. More importantly, many of the most radical LGBT people identify as queer and adopt this approach to political organising: the last year, for example, has seen the establishment in London of UK Uncut-style group Queer Resistance, and of the trade unionist group Queers Against the Cuts. This article traces the development of queer theory and politics, and assesses their claim to provide a radical alternative to what they see as the LGBT mainstream.

{ International Socialism | Continue reading }

artwork { Richard Prince }

ideas | March 12th, 2012 2:00 pm

haha, ideas, visual design | March 11th, 2012 6:47 pm

Phenomenology is commonly understood in either of two ways: as a disciplinary field in philosophy, or as a movement in the history of philosophy.

The discipline of phenomenology may be defined initially as the study of structures of experience, or consciousness. Literally, phenomenology is the study of “phenomena”: appearances of things, or things as they appear in our experience, or the ways we experience things, thus the meanings things have in our experience. Phenomenology studies conscious experience as experienced from the subjective or first person point of view. This field of philosophy is then to be distinguished from, and related to, the other main fields of philosophy: ontology (the study of being or what is), epistemology (the study of knowledge), logic (the study of valid reasoning), ethics (the study of right and wrong action), etc.

The historical movement of phenomenology is the philosophical tradition launched in the first half of the 20th century by Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre, et al. In that movement, the discipline of phenomenology was prized as the proper foundation of all philosophy — as opposed, say, to ethics or metaphysics or epistemology. The methods and characterization of the discipline were widely debated by Husserl and his successors, and these debates continue to the present day. (The definition of phenomenology offered above will thus be debatable, for example, by Heideggerians, but it remains the starting point in characterizing the discipline.)

{ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | Continue reading }

art { Andy Goldsworthy, Spire, 2008 }

ideas | March 11th, 2012 3:19 pm

I wanted to slit my fucking wrists. Look at this world, it’s all so shallow. You want me to pay eighty bucks to listen to you bitch about your mother for two hours? I don’t think so.

{ J.T. Rogers, on the state of contemporary American theater | via Boston to Brooklyn }

photo { Tommy Malekoff }

ideas | March 11th, 2012 3:00 pm

As for the love of the Other, or, worse, the “recognition of the Other,” these are nothing but Christian confections. There is never “the Other” as such. There are projects of thought, or of actions, on the basis of which we distinguish between those who are friends, those who are enemies, and those who can be considered neutral. The question of knowing how to treat enemies or neutrals depends entirely on the project concerned, the thought that constitutes it, and the concrete circumstances (is the project in an escalating phase? is it very dangerous? etc.).

{ Alain Badiou/Cabinet | Continue reading }

ideas | March 8th, 2012 3:04 pm

Amazon isn’t just a distributor, it’s a hoping to be the major publisher of e-books. When Amazon buys ebooks for $13 wholesale and sells them for $10 retail, and its gargantuan size means it can keep up the practice indefinitely, the strategy isn’t just jarring publishers into adopting lower price points. Because Amazon offers writers a better royalty for publishing directly, its pricing strategy is aimed at squeezing publishers out of the equation entirely.

{ Barry Ritholtz | Continue reading }

books, economics | March 8th, 2012 3:00 pm

In one experiment, the psychologists asked a group of Christian students to give their impressions of the personalities of two people. In all relevant respects, these two people were very similar – except one was a fellow Christian and the other Jewish. Under normal circumstances, participants showed no inclination to treat the two people differently. But if the students were first reminded of their mortality (e.g., by being asked to fill in a personality test that included questions about their attitude to their own death) then they were much more positive about their fellow Christian and more negative about the Jew.

The researchers behind this work – Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg and Tom Pyszczynski – were testing the hypothesis that most of what we do we do in order to protect us from the terror of death; what they call “Terror Management Theory.” Our sophisticated worldviews, they believe, exist primarily to convince us that we can defeat the Reaper. Therefore when he looms, scythe in hand, we cling all the more firmly to the shield of our beliefs.

This research, now spanning over 400 studies, shows what poets and philosophers have long known: that it is our struggle to defy death that gives shape to our civilization. (…)

The psychologists, psychiatrists and anthropologists who developed Terror Management Theory have shown that almost all ideologies, from patriotism to communism to celebrity culture, function similarly in shielding us from death’s approach. (…)

In one now classic secular example, the researchers recruited court judges from Tucson in the USA. Half of these judges were reminded of their mortality (again with the otherwise innocuous personality test) and half were not. They were then all asked to rule on a hypothetical case of prostitution similar to those they ruled on every day. The judges who had first been reminded of their mortality set a bond (the equivalent of bail) nine times higher than those who hadn’t (averaging $455 compared to $50).

So just like the Christians, they reacted to the thought of death by clinging more fiercely to their worldview.

{ New Humanist | Continue reading }

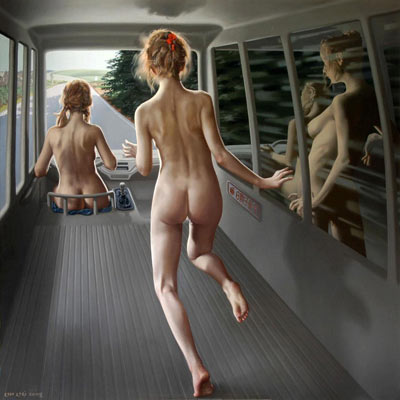

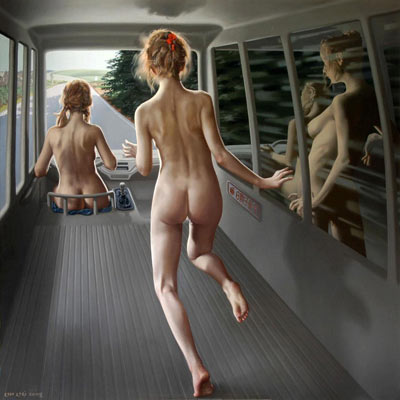

artwork { Lui Liu }

ideas, psychology | March 7th, 2012 4:14 pm

One of the interesting things about success is that we think we know what it means. A lot of the time our ideas about what it would mean to live successfully are not our own. They’re sucked in from other people. And we also suck in messages from everything from the television to advertising to marketing, et cetera. These are hugely powerful forces that define what we want and how we view ourselves. What I want to argue for is not that we should give up on our ideas of success, but that we should make sure that they are our own. We should focus in on our ideas and make sure that we own them, that we’re truly the authors of our own ambitions. Because it’s bad enough not getting what you want, but it’s even worse to have an idea of what it is you want and find out at the end of the journey that it isn’t, in fact, what you wanted all along.

{ Alain de Botton | TED video | Thanks Tim }

photo { Simen Johan }

ideas | March 5th, 2012 1:30 pm

In the philosophy of religion, the problem of evil is the question of how to explain evil if there exists a deity that is omnibenevolent, omnipotent, and omniscient.

Some philosophers have claimed that the existences of such a god and of evil are logically incompatible or unlikely.

Attempts to resolve the question under these contexts have historically been one of the prime concerns of theodicy.

Some responses include the arguments that true free will cannot exist without the possibility of evil, that humans cannot understand God, that suffering is necessary for spiritual growth or evil is the consequence of a fallen world. Others contend that God is not omnibenevolent or omnipotent.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

ideas | March 1st, 2012 2:17 pm

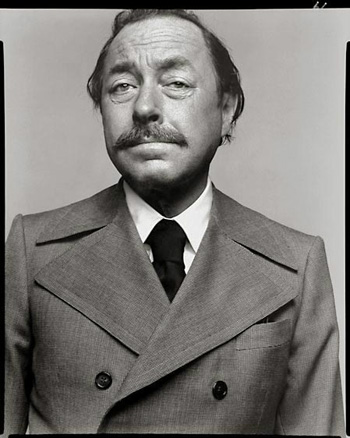

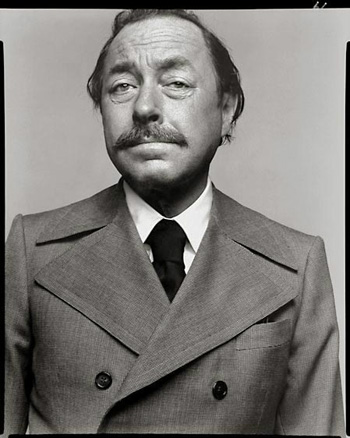

Since when did being a writer become a career choice, with appropriate degree courses and pecking orders? Does this state of affairs make any difference to what gets written?

At school we were taught two opposing visions of the writer as artist. He might be a skilled craftsman bringing his talent to the service of the community, which rewarded him with recognition and possibly money. This, they told us, was the classical position, as might be found in the Greece of Sophocles, or Virgil’s Rome, or again in Pope’s Augustan Britain. Alternatively the writer might make his own life narrative into art, indifferent to the strictures and censure of society but admired by it precisely because of his refusal to kowtow. This was the Romantic position as it developed in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. (…)

As we know, T.S. Eliot rather complicated matters by telling us that the writer had to overcome his personality and find his place in a literary tradition. (…)

Still, none of this prepared us for the advent of creative writing as a “career.” In the last thirty or forty years, the writer has become someone who works on a well-defined career track, like any other middle class professional, not, however, to become a craftsman serving the community, but to project an image of himself (partly through his writings, but also in dozens of other ways) as an artist who embodies the direction in which culture is headed.

{ NY Review of Books | Continue reading }

photo { Tennesse Williams by Richard Avedon }

related { The digitization of over five million books has created a huge dataset of cultural interest. Now researchers are beginning to tease it apart using powerful number-crunching techniques. | Culturomics and the Google Book Project }

books, ideas | March 1st, 2012 2:16 pm