Study: A 3 Second Interruption Doubles Your Odds of Messing Up

It’s called “contextual jitter” — in the time it takes to silence your cell phone, you’ve already lost track of what you were doing.

When their attention was shifted from the task at hand for a mere 2.8 seconds, they became twice as likely to mess up the sequence. The error rate tripled when the interruptions averaged 4.4 seconds.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

psychology |

July 15th, 2014

Few human possessions are so universally owned as mobile phones. There are almost as many mobile phones as there are humans on the planet. More people worldwide own mobile phones than have access to working toilets. These devices not only help individuals share information with each other, they are increasingly being used to help individuals gather information about themselves. Smartphones — mobile phones with built in applications and internet access — have rapidly become one of the world’s most sophisticated self-tracking tools. Self-trackers and those engaged in the “quantified self” movement are using smartphones to collect large volumes of data about their health, their environment, and the interaction between the two. Continuous tracking is now obtainable for personal health indicators including physical activity, brain activity, mood dynamics, numerous physiologic metrics and demographic data. Similarly, smartphones are empowering individuals to measure and map, at a relatively low cost, environmental data on air quality, water quality, temperature, humidity, noise levels, and more.

Mobile phones can provide another source of information to their owners: sample data on their personal microbiome. The personal microbiome, here defined as the collection of microbes associated with an individual’s personal effects (i.e., possessions regularly worn or carried on one’s person), likely varies uniquely from person to person. Research has shown there can be significant interpersonal variation in human microbiota, including for those microbes found on the skin. We hypothesize that this variation can be detected not just in the human microbiome, but also on the phone microbiome.

{ Meadow/Altrichter/Green | Continue reading }

germs, health, technology |

July 15th, 2014

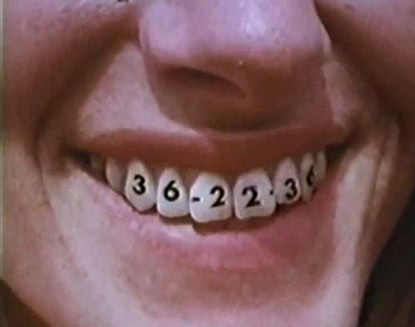

Recent experimental studies show that emotions can have a significant effect on the way we think, decide, and solve problems. This paper presents a series of four experiments on how emotions affect logical reasoning.

In two experiments different groups of participants first had to pass a manipulated intelligence test. Their emotional state was altered by giving them feedback, that they performed excellent, poor or on average. Then they completed a set of logical inference problems (with if p, then q statements) either in a Wason selection task paradigm or problems from the logical propositional calculus.

Problem content also had either a positive, negative or neutral emotional value. Results showed a clear effect of emotions on reasoning performance. Participants in negative mood performed worse than participants in positive mood, but both groups were outperformed by the neutral mood reasoners.

Problem content also had an effect on reasoning performance. In a second set of experiments, participants with exam or spider phobia solved logical problems with contents that were related to their anxiety disorder (spiders or exams). Spider phobic participants’ performance was lowered by the spider-content, while exam anxious participants were not affected by the exam-related problem content.

Overall, unlike some previous studies, no evidence was found that performance is improved when emotion and content are congruent. These results have consequences for cognitive reasoning research and also for cognitively oriented psychotherapy and the treatment of disorders like depression and anxiety.

{ Frontiers | Continue reading }

photo { Ester Grass Vergara }

psychology |

July 15th, 2014

Trivers (1976) introduced his theory of self-deception over three decades ago. According to his theory, individuals deceive themselves to better deceive others by placing truthful information in the unconscious while consciously presenting false information to others as well as the self without leaving cues to be detected of deception. […]

Humans and other primates live in hierarchical social groups where status influences resource distribution. High-status individuals who attained their position either by force or social intelligence have more resources than low-status individuals and have the power to punish the latter for rule violations. Low-status individuals who are under constant surveillance often attempt to hide resources from high-status individuals. In this case, low-status individuals should be more motivated to deceive, whereas high-status individuals should be more motivated to detect deception. High-status individuals have more honest means (through force or by changing the rules) to acquire resources than do low-status individuals. High-status individuals also have more resources—including information leading to the deception detection—and the means to punish deceivers. In contrast, low-status individuals are more limited detectors who may face revenge for detecting deception. Detecting deception does not enhance fitness if the detector is unable to punish but may be retaliated by the deceiver. There is thus more pressure to perfect deception when one has the need to deceive but also faces increased chances to be caught and punished. The same pressure to better deceive is much reduced when one expects little punishment from the detector if caught deceiving or has other honest means to pursue the same fitness gains. Social status may therefore shift selection pressure to favor low-status individuals over high-status individuals as fearful deceivers and the high-status individuals over low-status individuals as vigilant detectors. Thus, Trivers’ arms race between deception and detection is likely to have played out between low-status deceivers and high-status detectors, leading to people deceiving themselves to better deceive high- rather than low- or equal-status others. […]

According to Trivers (2000), a blatant deceiver keeps both true and false information in the conscious mind but presents only falsehoods to others. In doing so, the deceiver may leave clues about the truth due to its conscious access. A self-deceiver keeps only false information in consciousness. Lying to others and to the self at the same time, the self-deceiver thus leaves no clues about the truth retained in the unconscious mind. […]

Memory and its distortion may be temporarily employed first to keep truthful information away from both self and others and later to retrieve accurate information to benefit the self. Using a dual-retrieval paradigm, we tested the hypothesis that people are likely to deceive themselves to better deceive high- rather than equal-status others.

College student participants were explicitly instructed (Study 1 and 2) or induced (Study 3) to deceive either a high-status teacher or an equal-status fellow student. When interacting with the high- but not equal-status target, participants in three studies genuinely remembered fewer previously studied items than they did on a second memory test alone without the deceiving target.

The results support the view that self-deception responds to status hierarchy that registers probabilities of deception detection such that people are more likely to self-deceive high- rather than equal-status others.

{ Evolution Psychology | PDF }

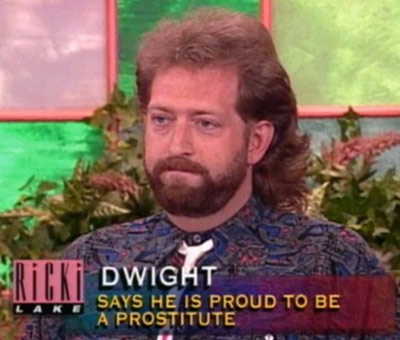

art { Eric Yahnker }

psychology, relationships |

July 11th, 2014

Anyone we could marry would, of course, be a little wrong for us. It is wise to be appropriately pessimistic here. Perfection is not on the cards. Unhappiness is a constant. Nevertheless, one encounters some couples of such primal, grinding mismatch, such deep-seated incompatibility, that one has to conclude that something else is at play beyond the normal disappointments and tensions of every long-term relationship: some people simply shouldn’t be together. […]

Given that marrying the wrong person is about the single easiest and also costliest mistake any of us can make, it is extraordinary, and almost criminal, that the issue of marrying intelligently is not more systematically addressed at a national and personal level, as road safety or smoking are.

{ Philosophers’ Mail | Continue reading }

image { Ms. America/The New Inquiry }

relationships |

July 10th, 2014

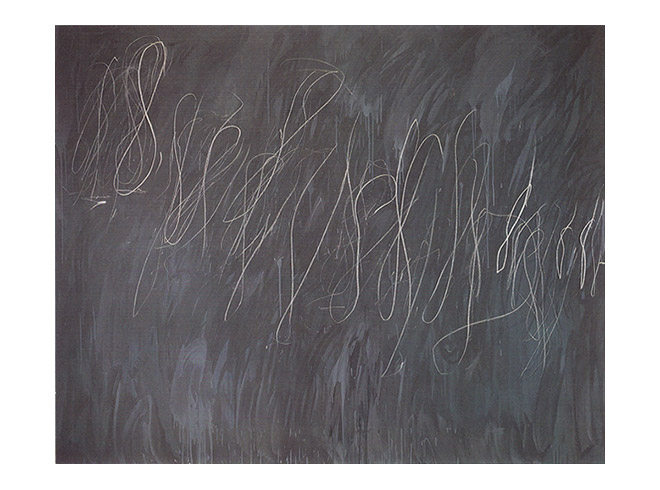

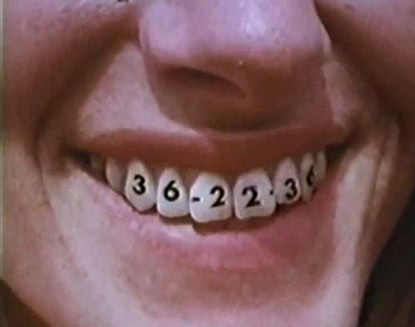

Haberman wanted grocery stores to embrace the 12-digit Universal Product Code—better known as the barcode—to create a standardized system for tracking inventory and speeding checkout. He took his fellow execs to a nice dinner. Then, as was the fashion at the time, they went to see Deep Throat. […]

Without the barcode, FedEx couldn’t guarantee overnight delivery. […] Nearly all babies born today in U.S. hospitals get barcode bracelets as soon as they’re swaddled.

{ Wired | Continue reading }

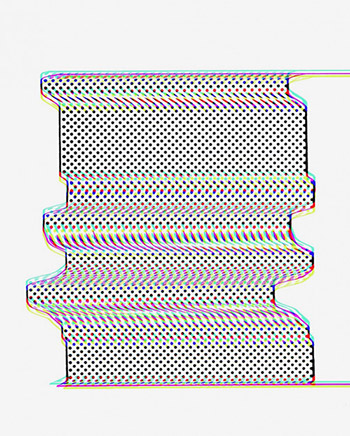

art { Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1968 }

economics, technology |

July 10th, 2014

I no longer look at somebody’s CV to determine if we will interview them or not,” declares Teri Morse, who oversees the recruitment of 30,000 people each year at Xerox Services. Instead, her team analyses personal data to determine the fate of job candidates.

She is not alone. “Big data” and complex algorithms are increasingly taking decisions out of the hands of individual interviewers – a trend that has far-reaching consequences for job seekers and recruiters alike. […]

Employees who are members of one or two social networks were found to stay in their job for longer than those who belonged to four or more social networks (Xerox recruitment drives at gaming conventions were subsequently cancelled). Some findings, however, were much more fundamental: prior work experience in a similar role was not found to be a predictor of success.

“It actually opens up doors for people who would never have gotten to interview based on their CV,” says Ms Morse.

{ FT | Continue reading }

related { Big Data hopes to liberate us from the work of self-construction—and justify mass surveillance in the process }

economics, social networks, technology |

July 10th, 2014

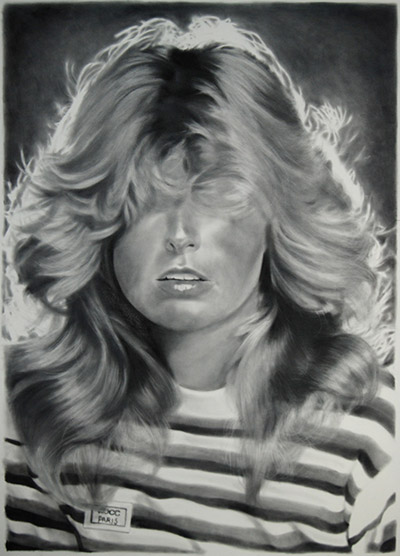

The term “stress” had none of its contemporary connotations before the 1920s. It is a form of the Middle English destresse, derived via Old French from the Latin stringere, “to draw tight.” The word had long been in use in physics to refer to the internal distribution of a force exerted on a material body, resulting in strain. In the 1920s and 1930s, biological and psychological circles occasionally used the term to refer to a mental strain or to a harmful environmental agent that could cause illness.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

The modern idea of stress began on a rooftop in Canada, with a handful of rats freezing in the winter wind.

This was 1936 and by that point the owner of the rats, an endocrinologist named Hans Selye, had become expert at making rats suffer for science.

“Almost universally these rats showed a particular set of signs,” Jackson says. “There would be changes particularly in the adrenal gland. So Selye began to suggest that subjecting an animal to prolonged stress led to tissue changes and physiological changes with the release of certain hormones, that would then cause disease and ultimately the death of the animal.”

And so the idea of stress — and its potential costs to the body — was born.

But here’s the thing: The idea of stress wasn’t born to just any parent. It was born to Selye, a scientist absolutely determined to make the concept of stress an international sensation.

{ NPR | Continue reading }

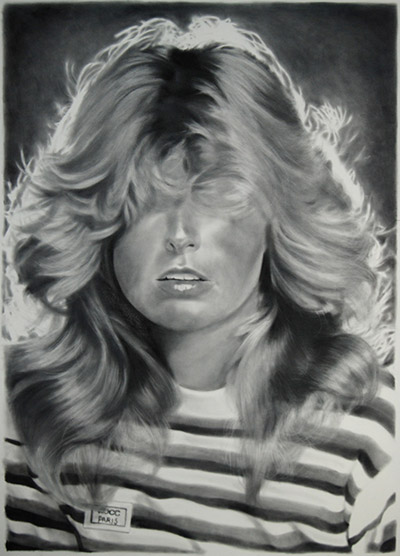

art { Richard Phillips, Blauvelt, 2013 }

Linguistics, flashback, health |

July 10th, 2014

Drawing on theorizing and research suggesting that people are motivated to view their world as an orderly and predictable place in which people get what they deserve, the authors proposed that (a) random and uncontrollable bad outcomes will lower self-esteem and (b) this, in turn, will lead to the adoption of self-defeating beliefs and behaviors.

Four experiments demonstrated that participants who experienced or recalled bad (vs. good) breaks devalued their self-esteem (Studies 1a and 1b), and that decrements in self-esteem (whether arrived at through misfortune or failure experience) increase beliefs about deserving bad outcomes (Studies 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b). Five studies (Studies 3–7) extended these findings by showing that this, in turn, can engender a wide array of self-defeating beliefs and behaviors, including claimed self-handicapping ahead of an ability test (Study 3), the preference for others to view the self less favorably (Studies 4–5), chronic self-handicapping and thoughts of physical self-harm (Study 6), and choosing to receive negative feedback during an ability test (Study 7).

The current findings highlight the important role that concerns about deservingness play in the link between lower self-esteem and patterns of self-defeating beliefs and behaviors. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

{ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | PDF }

psychology |

July 7th, 2014

When humans fight hand-to-hand the face is usually the primary target and the bones that suffer the highest rates of fracture are the parts of the skull that exhibit the greatest increase in robusticity during the evolution of basal hominins. These bones are also the most sexually dimorphic parts of the skull in both australopiths and humans. In this review, we suggest that many of the facial features that characterize early hominins evolved to protect the face from injury during fighting with fists. Specifically, the trend towards a more orthognathic face; the bunodont form and expansion of the postcanine teeth; the increased robusticity of the orbit; the increased robusticity of the masticatory system, including the mandibular corpus and condyle, zygoma, and anterior pillars of the maxilla; and the enlarged jaw adductor musculature are traits that may represent protective buttressing of the face.

If the protective buttressing hypothesis is correct, the primary differences in the face of robust versus gracile australopiths may be more a function of differences in mating system than differences in diet as is generally assumed. In this scenario, the evolution of reduced facial robusticity in Homo is associated with the evolution of reduced strength of the upper body and, therefore, with reduced striking power.

The protective buttressing hypothesis provides a functional explanation for the puzzling observation that although humans do not fight by biting our species exhibits pronounced sexual dimorphism in the strength and power of the jaw and neck musculature. The protective buttressing hypothesis is also consistent with observations that modern humans can accurately assess a male’s strength and fighting ability from facial shape and voice quality.

{ Biological Reviews | Continue reading }

faces, science |

July 7th, 2014

South African Doctors Surgically Remove Cell Phone Lodged In Man’s Mouth

South African Doctors Surgically Remove Cell Phone Lodged In Man’s Mouth

People voluntarily leaving jobs at highest rate since 2009 downturn

99% of the plastic we throw in the ocean has mysteriously disappeared

More left-handed men are born during the winter

Why Do Some Teens Become Binge Drinkers? Algorithms Answer.

Consciousness on-off switch discovered deep in brain

Less Sleep Means Smaller Brains in Older Adults

Scientists are using hypnosis to understand why some people believe they’re inhabited by paranormal beings.

Genetic link to autism found

Twenty epidemiologic studies have shown that neither thimerosal nor MMR vaccine causes autism

For a long list of investment “biases,” including lack of diversification, excessive trading, and the disposition effect, we find that genetic differences explain up to 45% of the remaining variation across individual investors, after controlling for observable individual characteristics.

Practice accounted for about 26% of individual differences in performance for games, about 21% of individual differences in music, and about 18% of individual differences in sports. But it only accounted for about 4% of individual differences in education and less than 1% of individual differences in performance in professions. Becoming an expert takes more than practice

Don’t Try Losing Weight By Just Eating More Fruits And Vegetables

“Super Bananas” Enter U.S. Market Trials

Why not even exercise will undo the harm of sitting all day—and what you can do about it

How do mosquitoes find some people and not others?

A Contraceptive Implant with Remote Control

Hacking into Internet Connected Light Bulbs

Breakthrough in guessing the risk of popping a balloon

New State of Matter Discovered

Another group ended up believing that quantum mechanics did represent reality, and that, yes, reality was non-local, and possibly not very real either. Quantum state may be a real thing

Colonizing Venus

While on an expedition into Africa during the late 19th century, Jameson, heir to an Irish whiskey manufacturer, reportedly bought an 11-year-old girl and offered her to cannibals to document and sketch how she was cooked and eaten. [+ NY Times | PDF]

Darwin may be the first person to ever notice a puzzling phenomenon: the bafflingly long time it takes kids to learn the meanings of color words.

The codpiece, however, may have been a disguise for underlying disease.

8 Summer Miseries Made Worse by Global Warming, From Poison Ivy to Allergies

New York’s unofficial shuttles, called “dollar vans” in some neighborhoods, make up a thriving transportation system that operates where the subway and buses don’t.

When Dany Levy sold her email newsletter DailyCandy to Comcast for $125 million, she thought she was fortifying the future of the company. This is what happened next.

The dark side of Twitter — Infidelity, break-ups, and divorce

Fake Followers for Hire, and How to Spot Them

Self-refuting sentence of the week

Dictionary of Untranslatables

10 Tricks to Appear Smart During Meetings

Google camera selfies

Retail Sluts

every day the same again |

July 6th, 2014

This study compared the effectiveness of four classic moral stories in promoting honesty in 3- to 7-year-olds. Surprisingly, the stories of “Pinocchio” and “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” failed to reduce lying in children. In contrast, the apocryphal story of “George Washington and the Cherry Tree” significantly increased truth telling. Further results suggest that the reason for the difference in honesty-promoting effectiveness between the “George Washington” story and the other stories was that the former emphasizes the positive consequences of honesty, whereas the latter focus on the negative consequences of dishonesty.

{ Psychological Science | PDF }

art { Sara Cwynar, Print Test Panel (Darkroom Manuals), 2013 }

kids, psychology |

July 2nd, 2014

In the language of social psychology, the situationist view attributes behavior mainly to external, rather than internal forces. Hence, heroism and villainy are unrelated to individual differences in personality or even conscious decisions based on one’s values. This seems to imply a rather passive view of human behavior in which people are largely at the mercy of circumstances outside themselves, rather than rational actors capable of making choices. However, if features of the person can be disregarded in favour of situational forces, then it is very difficult to explain why it is that the same situation can elicit completely opposite responses from different people. This would seem to suggest that situations elicit either heroic or villainous responses in a random way that cannot be predicted, or that situational factors alone are insufficient to explain the choices that people make in difficult circumstances. An alternative view is that situations do not so much suppress the individual personality, as reveal the person’s latent potential (Krueger, 2008). Therefore, a dangerous situation for example might reveal one person’s potential for bravery and another’s potential for cowardice.

{ Eye on Psych | Continue reading }

psychology |

July 1st, 2014

A team of researchers has found that releasing excess heat from air conditioners running during the night resulted in higher outside temperatures, worsening the urban heat island effect and increasing cooling demands.

{ Phys | Continue reading }

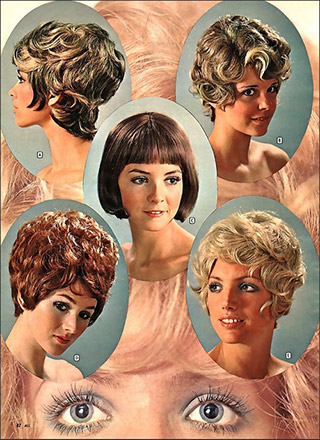

scan { Hans-Peter Feldmann, Catalogue, 2012 }

climate, haha |

June 30th, 2014

Fastest-Growing Metro Area in U.S. Has No Crime or Kids

Fastest-Growing Metro Area in U.S. Has No Crime or Kids

Decline of religion in the West has created a rise in black magic, Satanism and the occult. We need more exorcists, say Catholics.

A common but little-known practice in corporate America: Companies are taking out life insurance policies on their employees, and collecting the benefits when they die. [NY Times]

Every American Killed by Lightning So Far in 2014 Has Been Male

The articulation of vowels systematically influences our feelings and vice versa.

Recognizing faces despite amnesia

Ford And Intel Use Facial Recognition To Improve In-Car Tech, Safety

Economist Rick Nevin has an explanation for the 1990s dramatic drop in crime. After lead was banned from paint and gasoline in the 1970s, he says, fewer children suffered mental handicaps that can result from lead exposure, and eventually, lead to criminality. [Thanks Tim]

On the trail of the elusive successful psychopath

When does rude service at luxury stores make consumers go back for more?

The point is that Godzilla is not an external menace. Godzilla is built into the system. Godzilla is our way of life.

Are Ad Agencies Still Cool?

Peter Doig, art world phenomenon, set to eclipse Damien Hirst

Kara Walker’s sugar-coated sphinx

This face is unrecognizable to several state-of-art face detection algorithms

Spit masks [Thanks Tim]

every day the same again |

June 30th, 2014

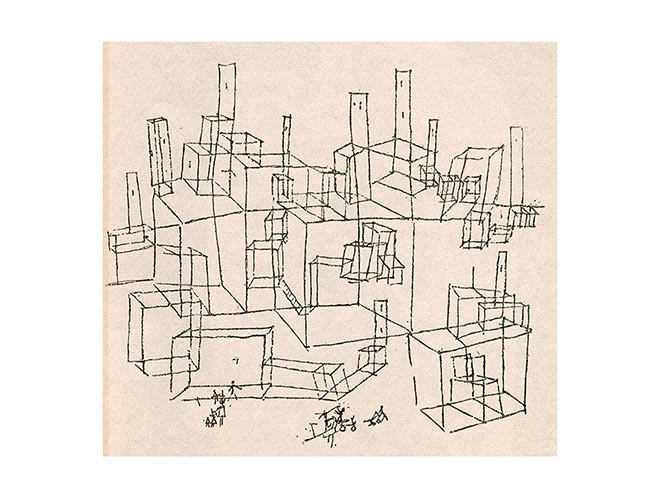

Four experiments examined the interplay of memory and creative cognition, showing that attempting to think of new uses for an object can cause the forgetting of old uses. […] Additionally, the forgetting effect correlated with individual differences in creativity such that participants who exhibited more forgetting generated more creative uses than participants who exhibited less forgetting. These findings indicate that thinking can cause forgetting and that such forgetting may contribute to the ability to think creatively.

{ APA/Psycnet | Continue reading }

art { Kazumasa Nagai }

ideas, psychology |

June 30th, 2014

The only cryonics storage facilities are in the US and Russia. So while my day job is as a student landlord, in my spare time I run Cryonics UK and train a cryonics emergency team in my own home. We’re ready to administer the medical procedures needed to stabilise and cool a body before it is flown to the US on dry ice.

Around 40 people are on our emergency list – people who can call us and say, “I’m going, please help me.” They pay roughly £20 a month to cover the upkeep of our equipment and ambulance. To call us out when the time comes costs about £20,000, plus there’s the cost of long-term storage. With Alcor, one of two US storage services, the total bill will be $95,000 for “head only” and $215,000 for “whole body”. Most people cover that with life insurance.

{ Financial Times | Continue reading }

mechanical robot, silicone, pigment and wig { Urs Fischer, Airports Are Like Nightclubs, 2004 }

economics, health |

June 30th, 2014