There are good reasons for any species to think darkly of its own extinction. […]

Simple, single-celled life appeared early in Earth’s history. A few hundred million whirls around the newborn Sun were all it took to cool our planet and give it oceans, liquid laboratories that run trillions of chemical experiments per second. Somewhere in those primordial seas, energy flashed through a chemical cocktail, transforming it into a replicator, a combination of molecules that could send versions of itself into the future.

For a long time, the descendants of that replicator stayed single-celled. They also stayed busy, preparing the planet for the emergence of land animals, by filling its atmosphere with breathable oxygen, and sheathing it in the ozone layer that protects us from ultraviolet light. Multicellular life didn’t begin to thrive until 600 million years ago, but thrive it did. In the space of two hundred million years, life leapt onto land, greened the continents, and lit the fuse on the Cambrian explosion, a spike in biological creativity that is without peer in the geological record. The Cambrian explosion spawned most of the broad categories of complex animal life. It formed phyla so quickly, in such tight strata of rock, that Charles Darwin worried its existence disproved the theory of natural selection.

No one is certain what caused the five mass extinctions that glare out at us from the rocky layers atop the Cambrian. But we do have an inkling about a few of them. The most recent was likely borne of a cosmic impact, a thudding arrival from space, whose aftermath rained exterminating fire on the dinosaurs. […]

Nuclear weapons were the first technology to threaten us with extinction, but they will not be the last, nor even the most dangerous. […] There are still tens of thousands of nukes, enough to incinerate all of Earth’s dense population centers, but not enough to target every human being. The only way nuclear war will wipe out humanity is by triggering nuclear winter, a crop-killing climate shift that occurs when smoldering cities send Sun-blocking soot into the stratosphere. But it’s not clear that nuke-levelled cities would burn long or strong enough to lift soot that high. […]

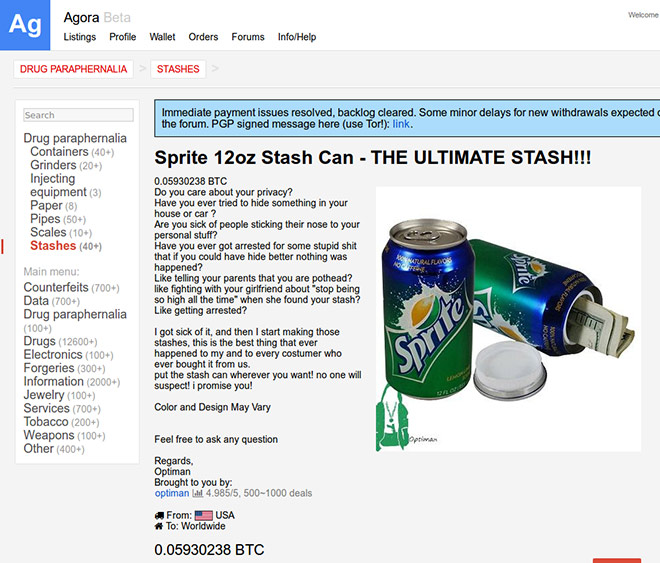

Humans have a long history of using biology’s deadlier innovations for ill ends; we have proved especially adept at the weaponisation of microbes. In antiquity, we sent plagues into cities by catapulting corpses over fortified walls. Now we have more cunning Trojan horses. We have even stashed smallpox in blankets, disguising disease as a gift of good will. Still, these are crude techniques, primitive attempts to loose lethal organisms on our fellow man. In 1993, the death cult that gassed Tokyo’s subways flew to the African rainforest in order to acquire the Ebola virus, a tool it hoped to use to usher in Armageddon. In the future, even small, unsophisticated groups will be able to enhance pathogens, or invent them wholesale. Even something like corporate sabotage, could generate catastrophes that unfold in unpredictable ways. Imagine an Australian logging company sending synthetic bacteria into Brazil’s forests to gain an edge in the global timber market. The bacteria might mutate into a dominant strain, a strain that could ruin Earth’s entire soil ecology in a single stroke, forcing 7 billion humans to the oceans for food. […]

The average human brain can juggle seven discrete chunks of information simultaneously; geniuses can sometimes manage nine. Either figure is extraordinary relative to the rest of the animal kingdom, but completely arbitrary as a hard cap on the complexity of thought. If we could sift through 90 concepts at once, or recall trillions of bits of data on command, we could access a whole new order of mental landscapes. It doesn’t look like the brain can be made to handle that kind of cognitive workload, but it might be able to build a machine that could. […]

To understand why an AI might be dangerous, you have to avoid anthropomorphising it. […] You can’t picture a super-smart version of yourself floating above the situation. Human cognition is only one species of intelligence, one with built-in impulses like empathy that colour the way we see the world, and limit what we are willing to do to accomplish our goals. But these biochemical impulses aren’t essential components of intelligence. They’re incidental software applications, installed by aeons of evolution and culture. Bostrom told me that it’s best to think of an AI as a primordial force of nature, like a star system or a hurricane — something strong, but indifferent. If its goal is to win at chess, an AI is going to model chess moves, make predictions about their success, and select its actions accordingly. It’s going to be ruthless in achieving its goal, but within a limited domain: the chessboard. But if your AI is choosing its actions in a larger domain, like the physical world, you need to be very specific about the goals you give it. […]

‘The really impressive stuff is hidden away inside AI journals,’ Dewey said. He told me about a team from the University of Alberta that recently trained an AI to play the 1980s video game Pac-Man. Only they didn’t let the AI see the familiar, overhead view of the game. Instead, they dropped it into a three-dimensional version, similar to a corn maze, where ghosts and pellets lurk behind every corner. They didn’t tell it the rules, either; they just threw it into the system and punished it when a ghost caught it. ‘Eventually the AI learned to play pretty well,’ Dewey said. ‘That would have been unheard of a few years ago, but we are getting to that point where we are finally starting to see little sparkles of generality.’

{ Ross Andersen/Aeon | Continue reading }