spy & security

This has led researchers to ask the questions: How can we get mobile users to break out of their patterns, visit less frequented areas, and collect the data we need?

Researchers can’t force mobile users to behave in a certain way, but researchers at Northwestern University have found that they may be able to nudge them in the right direction by using incentives that are already part of their regular mobile routine.

“We can rely on good luck to get the data that we need,” Bustamante said, “or we can ‘soft control’ users with gaming or social network incentives to drive them where we want them.”

{ McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science | Continue reading }

related { What Privacy Advocates Don’t Get About Data Tracking on the Web }

related { Google regularly receives requests from government agencies and courts around the world to remove content from our services and hand over user data | Who Does Facebook Think You Are Searching For? | Thanks Samantha! }

horror, spy & security, technology | March 16th, 2012 6:37 pm

Facebook’s inventory of data and its revenue from advertising are small potatoes compared to some others. Google took in more than 10 times as much, with an estimated $36.5 billion in advertising revenue in 2011, by analyzing what people sent over Gmail and what they searched on the Web, and then using that data to sell ads. Hundreds of other companies have also staked claims on people’s online data by depositing software called cookies or other tracking mechanisms on people’s computers and in their browsers. If you’ve mentioned anxiety in an e-mail, done a Google search for “stress” or started using an online medical diary that lets you monitor your mood, expect ads for medications and services to treat your anxiety.

Ads that pop up on your screen might seem useful, or at worst, a nuisance. But they are much more than that. The bits and bytes about your life can easily be used against you. Whether you can obtain a job, credit or insurance can be based on your digital doppelgänger — and you may never know why you’ve been turned down.

Material mined online has been used against people battling for child custody or defending themselves in criminal cases. LexisNexis has a product called Accurint for Law Enforcement, which gives government agents information about what people do on social networks. The Internal Revenue Service searches Facebook and MySpace for evidence of tax evaders’ income and whereabouts, and United States Citizenship and Immigration Services has been known to scrutinize photos and posts to confirm family relationships or weed out sham marriages. Employers sometimes decide whether to hire people based on their online profiles, with one study indicating that 70 percent of recruiters and human resource professionals in the United States have rejected candidates based on data found online. A company called Spokeo gathers online data for employers, the public and anyone else who wants it. The company even posts ads urging “HR Recruiters — Click Here Now!” and asking women to submit their boyfriends’ e-mail addresses for an analysis of their online photos and activities to learn “Is He Cheating on You?”

Stereotyping is alive and well in data aggregation. Your application for credit could be declined not on the basis of your own finances or credit history, but on the basis of aggregate data — what other people whose likes and dislikes are similar to yours have done. If guitar players or divorcing couples are more likely to renege on their credit-card bills, then the fact that you’ve looked at guitar ads or sent an e-mail to a divorce lawyer might cause a data aggregator to classify you as less credit-worthy. When an Atlanta man returned from his honeymoon, he found that his credit limit had been lowered to $3,800 from $10,800. The switch was not based on anything he had done but on aggregate data. A letter from the company told him, “Other customers who have used their card at establishments where you recently shopped have a poor repayment history with American Express.” (…)

In 2007 and 2008, the online advertising company NebuAd contracted with six Internet service providers to install hardware on their networks that monitored users’ Internet activities and transmitted that data to NebuAd’s servers for analysis and use in marketing. For an average of six months, NebuAd copied every e-mail, Web search or purchase that some 400,000 people sent over the Internet.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

economics, marketing, spy & security, technology | February 6th, 2012 3:51 pm

Amy, a 20-year-old brunette at the University of California at Irvine, was on her laptop when she got an IM from a random guy nicknamed mistahxxxrightme, asking her for webcam sex. Out of the blue, like that. Amy told the guy off, but he IM’d again, saying he knew all about her, and to prove it he started describing her dorm room, the color of her walls, the pattern on her sheets, the pictures on her walls. “You have a pink vibrator,” he said. It was like Amy’d slipped into a stalker movie. Then he sent her an image file. Amy watched in horror as the picture materialized on the screen: a shot of her in that very room, naked on the bed, having webcam sex with James.

Mistah X wasn’t done. The hacker fired off a note to James’s ex-girlfriend Carla Gagnon: “nice video I hope you still remember this if you want to chat and find out before I put it online hit me up.” Attached was a video still of her in the nude. Then the hacker contacted James directly, boasting that he had control of his computer, and it became clear this wasn’t about sex: He was toying with them. As Mistah X taunted James, his IMs filling the screen, James called Amy: He had the creep online. What should he do? They talked about calling the cops, but no sooner had James said the words than the hacker reprimanded him. “I know you’re talking to each other right now!” he wrote. James’s throat constricted; how did the stalker know what he was saying? Did he bug his room?

They were powerless. Amy decided to call the cops herself. But the instant she phoned the dispatcher, a message chimed on her screen. It was from the hacker. “I know you just called the police,” he wrote. (…)

The task of hunting him down fell to agents Tanith Rogers and Jeff Kirkpatrick of the FBI’s cyber program in Los Angeles. (…)

Luis Mijangos was an unlikely candidate for the world’s creepiest hacker. He lived at home with his mother, half brother, two sisters—one a schoolgirl, the other a housekeeper—and a perky gray poodle named Petra. It was a lively place, busy with family who gathered to watch soccer and to barbecue on the marigold-lined patio. Mijangos had a small bedroom in front, decorated in the red, white, and green of Mexican soccer souvenirs, along with a picture of Jesus. That’s where he spent most of his time, in front of his laptop—sitting in his wheelchair. (…)

In the early days of cybercrime, hackers had to code their software from scratch, but as he searched the Web, Mijangos found dozens of programs, with names like SpyNet and Poison Ivy, available cheaply, if not free. They allowed him to access someone’s desktop but limited the number of computers he could control simultaneously. Bragging to his peers, Mijangos says he found a way to modify an existing program that supported roughly thirty connections so that it could handle up to 600 computers at once.

{ GQ | Continue reading }

incidents, spy & security, technology | January 16th, 2012 8:16 am

Passwords are a pain to remember. What if a quick wiggle of five fingers on a screen could log you in instead? Or speaking a simple phrase? (…)

Computer scientists in Brooklyn are training their iPads to recognize their owners by the touch of their fingers as they make a caressing gesture. Banks are already using software that recognizes your voice, supplementing the standard PIN.

And after years of predicting its demise, security researchers are renewing their efforts to supplement and perhaps one day obliterate the old-fashioned password. (…)

The research arm of the Defense Department is looking for ways to use cues like a person’s typing quirks to continuously verify identity — in case, say, a soldier’s laptop ends up in enemy hands on the battlefield. In a more ordinary example, Google recently began nudging users to consider a two-step log-in system, combining a password with a code sent to their phones. Google’s latest Android software can unlock a phone when it recognizes the owner’s face or — not so safe — when it is tricked by someone holding up a photograph of the owner’s face.

Still, despite these recent advances, it may be premature to announce the end of passwords, as Bill Gates famously did in 2004, when he said “the password is dead.”

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

“After 10 years of studies, we find that the strengths as well as the consequences of technology are more profound than ever,” said Jeffrey I. Cole, director of the Center for the Digital Future. “At one extreme, we see users with the ability to have constant social connection, unlimited access to information, and unprecedented buying power. At the other extreme, we find extraordinary demands on our time, major concerns about privacy and vital questions about the proliferation of technology – including a range of issues that didn’t exist 10 years ago.

“We believe that America is at a major digital turning point,” said Cole. “Simply, we find tremendous benefits in online technology, but we also pay a personal price for those benefits. The question is: how high a price are we willing to pay?”

{ USC Annenberg | Continue reading }

spy & security, technology | December 31st, 2011 10:25 am

Robotics is a game-changer in national security. We now find military robots in just about every environment: land, sea, air, and even outer space. They have a full range of form-factors from tiny robots that look like insects to aerial drones with wingspans greater than a Boeing 737 airliner. Some are fixed onto battleships, while others patrol borders in Israel and South Korea; these have fully-auto modes and can make their own targeting and attack decisions. There’s interesting work going on now with micro robots, swarm robots, humanoids, chemical bots, and biological-machine integrations. As you’d expect, military robots have fierce names like: TALON SWORDS, Crusher, BEAR, Big Dog, Predator, Reaper, Harpy, Raven, Global Hawk, Vulture, Switchblade, and so on. But not all are weapons–for instance, BEAR is designed to retrieve wounded soldiers on an active battlefield.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

U.S., robots & ai, spy & security | December 21st, 2011 7:55 am

In Italy, all cargo containers carrying scrap metal get checked for radiation, by hand, before they’re allowed off the docks. At Voltri, this job falls to Montagna, a 49-year-old independent consultant certified as an expert in radiation detection by the Italian government. By the time he arrived that morning, longshoremen had gathered eleven 20-foot-long, 8-foot-wide containers from across the terminal, relying on manifests to determine which ones needed to be scanned. The boxes were lined up in two neat rows near the terminal’s entrance. (…)

He plugged in a heavy sensor wand and set the device on the ground 20 yards away from the containers. The Model 3 emits a high-pitched beep every time it detects a radioactive particle; Montagna turned it on, and the meter’s needle swung hard to the right, burying itself past the maximum reading of 500,000 counts per minute. Instead of its usual staccato chirps, the machine was whining continuously and frantically. (…)

Montagna realized that one of the containers in front of him held a lethal secret. But was that secret merely a slow-motion radioactive industrial accident—or a bomb, one that could decimate the Italian city’s entire 15-mile waterfront? Montagna ran back to his car to get a less sensitive detector. He didn’t give much thought to protection; at those radiation levels, he would have needed lead armor 5 inches thick to stand within a couple of feet of the source for very long.

Montagna took the new meter and walked up to the sealed boxes, circling each one in turn. Halfway down the second row, a crimson 20-footer with “TGHU 307703 0 22G1″ emblazoned in white on its side jerked the dials. As he passed a few feet from the box’s left side, Montagna was absorbing radiation equivalent to six chest x-rays per minute.

There are millions of containers just like TGHU 307703 0 22G1. The only thing that distinguished it from the steel boxes stacked in your local port or hitched to a truck one lane over during your morning commute—besides radiation a million times above normal background levels—was the painted-on identification number. (…)

Under the right conditions, just 20 milligrams of cesium-137—roughly the amount found in gadgets that hospitals use to calibrate their radiation therapy equipment—could contaminate 40 city blocks. (…)

The team then brought in one of the most sensitive portable detectors on the market, an $80,000 Ortec HPGe Detective DX-100T.

{ Wired | Continue reading }

spy & security, technology, uh oh | October 28th, 2011 11:00 am

Back in the day, when bad guys used telephones, the FBI and other law enforcement agencies would listen in with wiretaps. As long as phone companies cooperated—and they had to, by law—it was a relatively straightforward process. The Internet, however, separated providers of communications services—Skype, Facebook, Gmail—from those running the underlying infrastructure. Thus, even if the FBI obtains a suspect’s traffic data from their Internet service provider (ISP)—Comcast, Verizon, etc.—it may be difficult to make sense of it, especially if the suspect has been using encrypted services. This loophole has not been lost on child pornographers, drug traffickers, terrorists, and others who prize secret communications.

To catch up with the new technologies of malfeasance, FBI director Robert Mueller traveled to Silicon Valley last November to persuade technology companies to build “backdoors” into their products. If Mueller’s wish were granted, the FBI would gain undetected real-time access to suspects’ Skype calls, Facebook chats, and other online communications

{ Boston Review | Continue reading }

spy & security, technology | October 10th, 2011 10:30 am

An Australian technology expert has discovered Facebook tracks the websites its users visit after they leave the social networking site. Nik Cubrilovic said his tests showed Facebook did not delete its tracking cookies when you logged out but modified them, maintaining account information and other unique tokens that could identify you.

So whenever you visited a web page containing a Facebook button or widget, your browser was still sending the details back to Facebook, said Mr Cubrilovic. “Even if you are logged out, Facebook still knows and can track every page you visit,” he wrote in a blog post. “The only solution is to delete every Facebook cookie in your browser, or to use a separate browser for Facebook interactions.”

{ Sydney Morning Herald | Continue reading }

Facebook filed paperwork today to start FB PAC, a political action committee that will support candidates dedicated to protecting the online privacy of ordinary Americans at any cost. Kidding! The PAC will fund candidates who support “giving people the power to share,” i.e. stripping them of what few government privacy protections remain.

{ Gawker | Continue reading }

social networks, spy & security | September 27th, 2011 3:05 pm

Sybil accounts are fake identities created to unfairly increase the power or resources of a single malicious user. Researchers have long known about the existence of Sybil accounts in online communities such as file-sharing systems, but have not been able to perform large scale measurements to detect them or measure their activities. In this paper, we describe our efforts to detect, characterize and understand Sybil account activity in the Renren online social network (OSN). We use ground truth provided by Renren Inc. to build measurement based Sybil account detectors, and deploy them on Renren to detect over 100,000 Sybil accounts. We study these Sybil accounts, as well as an additional 560,000 Sybil accounts caught by Renren, and analyze their link creation behavior. Most interestingly, we find that contrary to prior conjecture, Sybil accounts in OSNs do not form tight-knit communities. Instead, they integrate into the social graph just like normal users. Using link creation timestamps, we verify that the large majority of links between Sybil accounts are created accidentally, unbeknownst to the attacker. Overall, only a very small portion of Sybil accounts are connected to other Sybils with social links. Our study shows that existing Sybil defenses are unlikely to succeed in today’s OSNs, and we must design new techniques to effectively detect and defend against Sybil attacks.

{ arXiv | Continue reading }

images { 1. Vitaly Virt | 2. Melvin Sokolsky }

halves-pairs, spy & security, technology | July 6th, 2011 6:41 pm

The nothing to hide argument is one of the primary arguments made when balancing privacy against security. In its most compelling form, it is an argument that the privacy interest is generally minimal to trivial, thus making the balance against security concerns a foreordained victory for security. Sometimes the nothing to hide argument is posed as a question: “If you have nothing to hide, then what do you have to fear?” Others ask: “If you aren’t doing anything wrong, then what do you have to hide?”

In this essay, I will explore the nothing to hide argument and its variants in more depth. Grappling with the nothing to hide argument is important, because the argument reflects the sentiments of a wide percentage of the population. In popular discourse, the nothing to hide argument’s superficial incantations can readily be refuted. But when the argument is made in its strongest form, it is far more formidable.

In order to respond to the nothing to hide argument, it is imperative that we have a theory about what privacy is and why it is valuable.

{ Daniel J. Solve, “I’ve Got Nothing to Hide” and Other Misunderstandings of Privacy | SSRN | Continue reading }

ideas, spy & security | June 4th, 2011 6:52 am

On April 30, 1943, a fisherman came across a badly decomposed corpse floating in the water off the coast of Huelva, in southwestern Spain. The body was of an adult male dressed in a trenchcoat, a uniform, and boots, with a black attaché case chained to his waist. His wallet identified him as Major William Martin, of the Royal Marines. (…)

It did not take long for word of the downed officer to make its way to German intelligence agents in the region. Spain was a neutral country, but much of its military was pro-German, and the Nazis found an officer in the Spanish general staff who was willing to help. A thin metal rod was inserted into the envelope; the documents were then wound around it and slid out through a gap, without disturbing the envelope’s seals. What the officer discovered was astounding. Major Martin was a courier, carrying a personal letter from Lieutenant General Archibald Nye, the vice-chief of the Imperial General Staff, in London, to General Harold Alexander, the senior British officer under Eisenhower in Tunisia. Nye’s letter spelled out what Allied intentions were in southern Europe. American and British forces planned to cross the Mediterranean from their positions in North Africa, and launch an attack on German-held Greece and Sardinia. Hitler transferred a Panzer division from France to the Peloponnese, in Greece, and the German military command sent an urgent message to the head of its forces in the region: “The measures to be taken in Sardinia and the Peloponnese have priority over any others.”

The Germans did not realize—until it was too late—that “William Martin” was a fiction. The man they took to be a high-level courier was a mentally ill vagrant who had eaten rat poison; his body had been liberated from a London morgue and dressed up in officer’s clothing. The letter was a fake, and the frantic messages between London and Madrid a carefully choreographed act. When a hundred and sixty thousand Allied troops invaded Sicily on July 10, 1943, it became clear that the Germans had fallen victim to one of the most remarkable deceptions in modern military history. (…)

Each stage of the deception had to be worked out in advance. Martin’s personal effects needed to be detailed enough to suggest that he was a real person, but not so detailed as to suggest that someone was trying to make him look like a real person. Cholmondeley and Montagu filled Martin’s pockets with odds and ends, including angry letters from creditors and a bill from his tailor. “Hour after hour, in the Admiralty basement, they discussed and refined this imaginary person, his likes and dislikes, his habits and hobbies, his talents and weaknesses,” Macintyre writes. “In the evening, they repaired to the Gargoyle Club, a glamorous Soho dive of which Montagu was a member, to continue the odd process of creating a man from scratch.” (…)

The dated papers in Martin’s pockets indicated that he had been in the water for barely five days. Had the Germans seen the body, though, they would have realized that it was far too decomposed to have been in the water for less than a week. And, had they talked to the Spanish coroner who examined Martin, they would have discovered that he had noticed various red flags. The doctor had seen the bodies of many drowned fishermen in his time, and invariably there were fish and crab bites on the ears and other appendages. In this case, there were none. Hair, after being submerged for a week, becomes brittle and dull. Martin’s hair was not. Nor did his clothes appear to have been in the water very long. But the Germans couldn’t talk to the coroner without blowing their cover. Secrecy stood in the way of accuracy.

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

flashback, spy & security | May 7th, 2011 10:07 am

For almost two years, Alex Pentland at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has tracked 60 families living in campus quarters via sensors and software on their smartphones—recording their movements, relationships, moods, health, calling habits and spending. In this wealth of intimate detail, he is finding patterns of human behavior that could reveal how millions of people interact at home, work and play.

Through these and other cellphone research projects, scientists are able to pinpoint “influencers,” the people most likely to make others change their minds. The data can predict with uncanny accuracy where people are likely to be at any given time in the future. Cellphone companies are already using these techniques to predict—based on a customer’s social circle of friends—which people are most likely to defect to other carriers.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

photo { Sarah Small }

spy & security, technology | April 23rd, 2011 7:22 pm

Forget passwords, tricky sums are more secure

Classic user identification requires the remote user sending a username and a password to the system to which they want to be authenticated. The system looks up the username in its locally stored database and if the password submitted matches the stored password, then access is granted. This method for identification works under the assumption there exist no malicious users and that their local terminals cannot be infected by malware. (…)

Nikolaos Bardis of the University of Military Education, in Vari, Greece and colleagues there and at the Polytechnic Institute of Kiev, in Ukraine, have developed an innovative approach to logins, which implements the advanced concept of zero knowledge identification.

Zero knowledge user identification solves these issues by using passwords that change for every session and are not known to the system beforehand. The system can only check their validity.

{ ScienceText | Continue reading }

mathematics, spy & security, technology | April 12th, 2011 3:17 pm

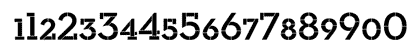

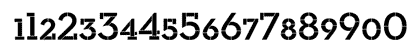

{ How the U.S. Secret Service pulls off the most complicated security event of the year, from counter-surveillance to counter-assault, hotel booking to event schedule. | The Atlantic | full story | Chart: The Presidential Motorcade }

U.S., pipeline, spy & security, transportation | February 9th, 2011 4:24 pm

U.S., spy & security, uh oh | July 21st, 2010 10:28 am

Their focus was Project B—Assange’s code name for a thirty-eight-minute video taken from the cockpit of an Apache military helicopter in Iraq in 2007. The video depicted American soldiers killing at least eighteen people, including two Reuters journalists; it later became the subject of widespread controversy, but at this early stage it was still a closely guarded military secret.

Assange is an international trafficker, of sorts. He and his colleagues collect documents and imagery that governments and other institutions regard as confidential and publish them on a Web site called WikiLeaks.org. Since it went online, three and a half years ago, the site has published an extensive catalogue of secret material, ranging from the Standard Operating Procedures at Camp Delta, in Guantánamo Bay, and the “Climategate” e-mails from the University of East Anglia, in England, to the contents of Sarah Palin’s private Yahoo account.

The catalogue is especially remarkable because WikiLeaks is not quite an organization; it is better described as a media insurgency. It has no paid staff, no copiers, no desks, no office. Assange does not even have a home. He travels from country to country, staying with supporters, or friends of friends—as he once put it to me, “I’m living in airports these days.” He is the operation’s prime mover, and it is fair to say that WikiLeaks exists wherever he does. At the same time, hundreds of volunteers from around the world help maintain the Web site’s complicated infrastructure; many participate in small ways, and between three and five people dedicate themselves to it full time. Key members are known only by initials—M, for instance—even deep within WikiLeaks, where communications are conducted by encrypted online chat services. The secretiveness stems from the belief that a populist intelligence operation with virtually no resources, designed to publicize information that powerful institutions do not want public, will have serious adversaries.

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

experience, pipeline, spy & security, technology | June 3rd, 2010 7:42 am

Two years ago, when the FBI was stymied by a band of armed robbers known as the “Scarecrow Bandits” that had robbed more than 20 Texas banks, it came up with a novel method of locating the thieves.

FBI agents obtained logs from mobile phone companies corresponding to what their cellular towers had recorded at the time of a dozen different bank robberies in the Dallas area. The voluminous records showed that two phones had made calls around the time of all 12 heists, and that those phones belonged to men named Tony Hewitt and Corey Duffey. A jury eventually convicted the duo of multiple bank robbery and weapons charges.

Even though police are tapping into the locations of mobile phones thousands of times a year, the legal ground rules remain unclear, and federal privacy laws written a generation ago are ambiguous at best. On Friday, the first federal appeals court to consider the topic will hear oral arguments (PDF) in a case that could establish new standards for locating wireless devices.

{ CNET | Continue reading }

spy & security, technology | March 4th, 2010 6:08 pm

Nearly the entire hit was recorded on closed-circuit TV cameras, from the time the team arrived at Dubai’s airport to the time the assassins entered Hamas military leader Mahmoud al-Mabhouh’s room. The cameras even caught team members before and after they donned their disguises. The only thing the Dubai authorities have been unable to discover is the true names of the team. But having identified the assassins, or at least the borrowed identities they traveled on, Dubai felt confident enough to point a finger at Israel. (Oddly enough several of the identities were stolen from people living in Israel.)

After Dubai released the tapes, the narrative quickly became that the assassination was an embarrassing blunder for Tel Aviv. Mossad failed spectacularly to assassinate a Hamas official in Amman in 1997— the poison that was used acted too slowly and the man survived—and it looks like the agency is not much better today. Why were so many people involved? (The latest report is that there were 26 members of the team.) Why were identities stolen from people living in Israel? Why didn’t they just kill Mr. Mabhouh in a dark alley, one assassin with a pistol with a silencer? Or why at least didn’t they all cover their faces with baseball caps so that the closed-circuit TV cameras did not have a clean view?

The truth is that Mr. Mabhouh’s assassination was conducted according to the book—a military operation in which the environment is completely controlled by the assassins. At least 25 people are needed to carry off something like this. You need “eyes on” the target 24 hours a day to ensure that when the time comes he is alone. You need coverage of the police—assassinations go very wrong when the police stumble into the middle of one. You need coverage of the hotel security staff, the maids, the outside of the hotel. You even need people in back-up accommodations in the event the team needs a place to hide.

I can only speculate about where exactly the hit went wrong. But I would guess the assassins failed to account for the marked advance in technology. Not only were there closed-circuit TV cameras in the hotel where Mr. Mabhouh was assassinated and at the airport, but Dubai has at its fingertips the best security consultants in the world. (…)

Not completely understanding advances in technology may be one explanation for the assassins nonchalantly exposing their faces to the closed-circuit TV cameras, one female assassin even smiling at one.

{ The Wall Street Journal | Continue reading }

guns, incidents, spy & security | March 4th, 2010 8:13 am

Back in the real world, of course, most major espionage activities look more like farce than anything else. I mean, the Bay of Pigs? Oliver North? Accidentally murdering suspected terrorists at Guantanamo Bay and then removing the corpses’ throats because, hyuk! hyuk!, gee nobody’ll notice that?

Clearly, the real secret of intelligence is that these people aren’t Machiavellian geniuses. They’re bumbling shitheads, just like most government functionaries—or, for that matter, most people.

{ Noah Berlatsky/Splice Today | Continue reading }

spy & security | February 25th, 2010 8:49 pm

{ Mata Hari in 1906 | Mata Hari was a Dutch-born erotic dancer and courtesan living in Paris who was executed by firing squad for espionage during World War I. | Wikipedia | Continue reading | More double agents }

flashback, photogs, spy & security | January 21st, 2010 8:02 pm