time

Thinking about eternity is not simply an esoteric mental exercise. It’s a cure for boredom. […]

Witness the man of stone. It takes an eternity for his eyes to blink even once. He stares at the sun, the moon, and the stars as they pass by turns overhead. One day he crumbles and only a pile of rubble remains. He wasn’t cut out for the eternal.

{ The Science Creative Quarterly | Continue reading }

photos { Nadav Kader }

ideas, photogs, time | May 15th, 2012 2:48 pm

A new study suggests that, by disrupting your body’s normal rhythms, your alarm clock could be making you overweight.

The study concerns a phenomenon called “social jetlag.” That’s the extent to which our natural sleep patterns are out of synch with our school or work schedules. Take the weekends: many of us wake up hours later than we do during the week, only to resume our early schedules come Monday morning. It’s enough to make your body feel like it’s spending the weekend in one time zone and the week in another. […]

Previous work with such data has already yielded some clues. “We have shown that if you live against your body clock, you’re more likely to smoke, to drink alcohol, and drink far more coffee,” says Roenneberg. […]

The researchers also found that people of all ages awoke and went to bed an average of 20 minutes later between 2002 and 2010. Work and school times have remained the same, meaning that social jetlag has increased during this period.

{ Science | Continue reading }

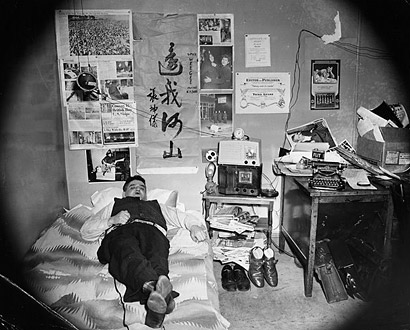

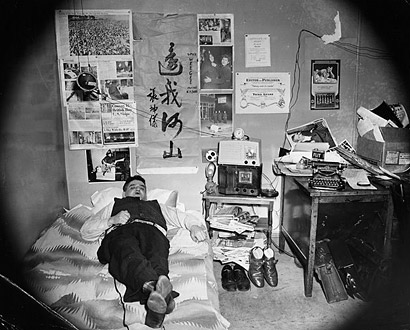

photo { Weegee in his apartment, police radio by his bedside }

health, science, sleep, time | May 11th, 2012 1:58 pm

Waking up from surgery can be disorienting. One minute you’re in an operating room counting backwards from 10, the next you’re in the recovery ward sans appendix, tonsils, or wisdom teeth. And unlike getting up from a good night’s sleep, where you know that you’ve been out for hours, waking from anesthesia feels like hardly any time has passed. Now, thanks to the humble honeybee, scientists are starting to understand this sense of time loss. New research shows that general anesthetics disrupt the social insect’s circadian rhythm, or internal clock, delaying the onset of timed behaviors such as foraging and mucking up their sense of direction. (…)

Warman says his team is currently looking at whether shining bright light at someone under anesthesia—a well known way to alter the circadian clock—could also reduce the procedure’s disorienting effects.

{ Science | Continue reading }

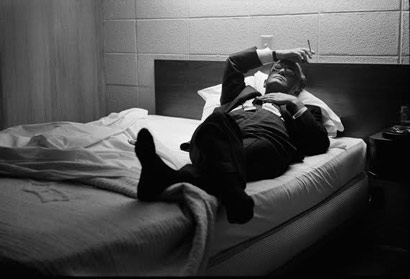

photo { Steve Shapiro, Truman Capote, Kansas, 1967 }

science, sleep, time | April 17th, 2012 10:27 am

The infinity or nunc stans [eternal Now] of thought (…) arises only when the arrow of infinite future possibility or anticipation meets with the infinite trajectory of the past as uncovered in memory. Infinite, here, does not mean eternal. It simply means that, so long as one lives, there is a non-denumerable infinity of possible future willings or anticipations, as well as of possible interpretations of past memories; there are a non-denumerable, unfixed number of possible past moments and future anticipations while one continues to live, as life is not absolutely predetermined. The present is described as a “diagonal” that intersects or transverses the past and the future. The constitutive moments of time, namely, the past, the present, and the future, are called “forces.”

{ The Role of forgetting in our experience of time | Parrhesia | | PDF }

photo { Alexander Harding }

ideas, time | February 17th, 2012 8:03 am

What occurred to Newton was that there was a force of gravity, which of course everybody knew about, it’s not like he actually discovered gravity– everybody knew there was such a thing as gravity. But if you go back into antiquity, the way that the celestial objects, the moon, the sun, and the planets, were treated by astronomy had nothing to do with the way things on earth were treated. These were entirely different realms, and what Newton realized was that there had to be a force holding the moon in orbit around the earth. This is not something that Aristotle or his predecessors thought, because they were treating the planets and the moon as though they just naturally went around in circles. Newton realized there had to be some force holding the moon in its orbit around the earth, to keep it from wandering off, and he knew also there was a force that was pulling the apple down to the earth. And so what suddenly struck him was that those could be one and the same thing, the same force.

(…)

I’m not sure it’s accurate to say that physicists want to hand time over to philosophers. Some physicists are very adamant about wanting to say things about it; Sean Carroll for example is very adamant about saying that time is real. You have others saying that time is just an illusion, that there isn’t really a direction of time, and so forth. I myself think that all of the reasons that lead people to say things like that have very little merit, and that people have just been misled, largely by mistaking the mathematics they use to describe reality for reality itself. If you think that mathematical objects are not in time, and mathematical objects don’t change — which is perfectly true — and then you’re always using mathematical objects to describe the world, you could easily fall into the idea that the world itself doesn’t change, because your representations of it don’t.

There are other, technical reasons that people have thought that you don’t need a direction of time, or that physics doesn’t postulate a direction of time. My own view is that none of those arguments are very good. To the question as to why a physicist would want to hand time over to philosophers, the answer would be that physicists for almost a hundred years have been dissuaded from trying to think about fundamental questions. I think most physicists would quite rightly say “I don’t have the tools to answer a question like ‘what is time?’ - I have the tools to solve a differential equation.” The asking of fundamental physical questions is just not part of the training of a physicist anymore.

(…)

On earth, of all the billions of species that have evolved, only one has developed intelligence to the level of producing technology. Which means that kind of intelligence is really not very useful. It’s not actually, in the general case, of much evolutionary value. We tend to think, because we love to think of ourselves, human beings, as the top of the evolutionary ladder, that the intelligence we have, that makes us human beings, is the thing that all of evolution is striving toward. But what we know is that that’s not true. Obviously it doesn’t matter that much if you’re a beetle, that you be really smart. If it were, evolution would have produced much more intelligent beetles. We have no empirical data to suggest that there’s a high probability that evolution on another planet would lead to technological intelligence. There is just too much we don’t know.

{ Tim Maudlin/The Atlantic | Continue reading }

photo { Luisa Opalesky }

ideas, science, space, time | January 22nd, 2012 3:35 pm

Coordinated universal time (UTC) is the time scale used all over the world for time coordination. It was established in 1972, based on atomic clocks, and was the successor of astronomical time, which is based on the Earth’s rotation. But since the atomic time scale drifts from the astronomical one, 1-second steps were added whenever necessary. In 1972 everybody was happy with this decision. Today, most systems we use for telecommunications are not really happy with these “leap” seconds. So in January member states of the International Telecommunications Union will vote on dropping the leap second. (…)

We are using a system that breaks time. The quality of time is continuity. This is why a majority in the international community want to change the definition of UTC and drop the leap second. (…)

It was agreed some years ago that we should not think of any kind of adjustment in the near future, the next 100 or 200 years. In about the year 2600 we will have a half-hour divergence. However, we don’t know how time-keeping will be then, or how technology will be. So we cannot rule for the next six or seven generations.

{ Felicitas Arias/Slate | Continue reading }

time | January 19th, 2012 3:19 pm

photogs, time, visual design | January 4th, 2012 6:26 pm

[November 11, 2011]

According to the historian Annemarie Schimmel in her book “The Mystery of Numbers,” medieval numerologists all considered the number one to represent divinity, unity or God. At the same time, though, scholars had absolutely nothing good to say about the number 11: “While every other number had at least one positive aspect, 11 was always interpreted in medieval [analysis] in a purely negative sense,” Schimmel wrote. The 16th-century numerologist Petrus Bungus even called 11 “the number of sinners and of penance.”

{ LiveScience }

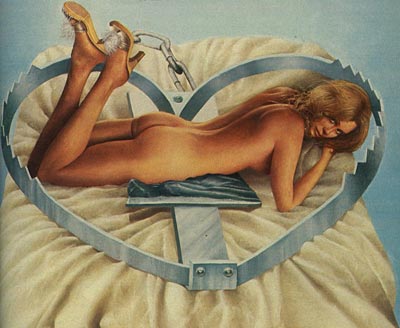

images { 1 | 2 }

flashback, time | November 4th, 2011 11:00 am

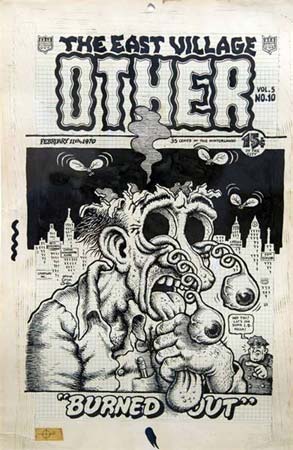

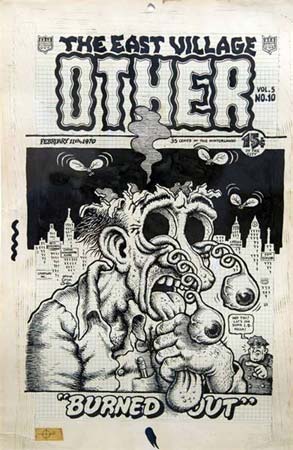

[In Time, 2011, directed by Andrew Niccol.]

Time is money: Everyone is genetically engineered to stop aging at 25; after that, people will live for only one more year unless they can gain access to more hours, days, weeks, etc. A cup of coffee costs four minutes, lunch at an upscale restaurant eight-and-a-half weeks. The distribution of wealth is about as lopsided as it is today, with the richest having at least a century remaining and the poorest surviving minute to minute. Each individual’s value is imprinted on the forearm as a clock, a string of 13 neon-green digits that suggests a cross between a concentration camp tattoo and a rave glow stick.

{ Village Voice | Overcoming Bias }

artwork { Charles Dana Gibson, Bedtime Story }

ideas, showbiz, time | October 31st, 2011 2:05 pm

future, ideas, time | October 24th, 2011 7:42 am

Today hardly anyone notices the equinox. Today we rarely give the sky more than a passing glance. We live by precisely metered clocks and appointment blocks on our electronic calendars, feeling little personal or communal connection to the kind of time the equinox once offered us. Within that simple fact lays a tectonic shift in human life and culture.

Your time — almost entirely divorced from natural cycles — is a new time. Your time, delivered through digital devices that move to nanosecond cadences, has never existed before in human history. As we rush through our overheated days we can barely recognize this new time for what it really is: an invention. (…)

Mechanical clocks for measuring hours did not appear until the fourteenth century. Minute hands on those clocks did not come into existence until 400 years later. Before these inventions the vast majority of human beings had no access to any form of timekeeping device. Sundials, water clocks and sandglasses did exist. But their daily use was confined to an elite minority.

{ Adam Frank/NPR | Continue reading }

The 12-hour clock can be traced back as far as Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: Both an Egyptian sundial for daytime use and an Egyptian water clock for night time use were found in the tomb of Pharaoh Amenhotep I. Dating to c. 1500 BC, these clocks divided their respective times of use into 12 hours each.

The Romans also used a 12-hour clock: daylight was divided into 12 equal hours (of, thus, varying length throughout the year) and the night was divided into four watches. The Romans numbered the morning hours originally in reverse. For example, “3 am” or “3 hours ante meridiem” meant “three hours before noon,” compared to the modern usage of “three hours into the first 12-hour period of the day.”

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Also: The terms “a.m.” and “p.m.” are abbreviations of the Latin ante meridiem (before midday) and post meridiem (after midday).

Linguistics, flashback, time | October 17th, 2011 8:36 am

If you ask a person when “middle age” begins, the answer, not surprisingly, depends on the age of that respondent. American college-aged students are convinced that one fits soundly into the middle-age category at 35. For respondents who are actually 35, middle age is half a decade away, with 40 representing the inaugural year. (…) Recently, a large sample of Swiss participants spanning several generations agreed with one another that middle-aged people are those who are between 35 to 53 years of age.

However, the precise chronological point at which we formally enter “middle age” is of little importance. (…) We’ve all heard of the dreaded “midlife crisis,” but what, exactly, is it? Furthermore, does it even exist as a scientifically valid concept? (…)

“Midlife crisis” was coined by Elliott Jacques in 1965. (…) According to him, the midlife crisis is such a crisis that many great artists and thinkers don’t even survive it. (…) He decided to crunch the numbers with a “random sample” of 310 such geniuses and, indeed, he discovered that a considerable number of these formidable talents—including Mozart, Raphael, Chopin, Rimbaud, Purcell, and Baudelaire—succumbed to some kind of tragic fate or another and drew their last breaths between the ages of 35 and 39. “The closer one keeps to genius in the sample,” Jacques observes, “the more striking and clear-cut is this spiking of the death rate in midlife.” (…)

Basically, argues Jacques, around the age of 35, genius can go in one of three directions. If you’re like that last batch of folks, you either die, literally, or else you perish metaphorically, having exhausted your potential early on in a sort of frenzied, magnificent chaos, unable to create anything approximating your former genius. The second type of individual, however, actually requires the anxieties of middle age—specifically, the acute awareness that one’s life is, at least, already half over—to reach their full creative potential. (…) Finally, the third type of creative genius is prolific and accomplished even in their earlier years, but their aesthetic or style changes dramatically at middle age, usually for the better. (…)

The phrase “midlife crisis” didn’t really creep into suburban vernacular as a catchall diagnosis until the late 1970s. This is when Yale’s Daniel Levinson, building on the stage theory tradition of lifespan developmentalist Erik Erikson, began popularizing tales of middle-class, middle-aged men who were struggling with transitioning to a time where “one is no longer young and yet not quite old.”

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

Linguistics, psychology, time | October 14th, 2011 12:12 pm

You live in the past. About 80 milliseconds in the past, to be precise (just slightly longer than the blink of an eye). Use one hand to touch your nose, and the other to touch one of your feet, at exactly the same time. You will experience them as simultaneous acts. But it takes more time for the signal to travel up your nerves from your feet to your brain than from your nose. The reconciliation is simple: our conscious experience takes time to assemble, and your brain waits for all the relevant input before it experiences the “now.” (…)

Aging can be reversed. (…) It’s only the universe as a whole that must increase in entropy, not every individual piece of it. Reversing the arrow of time for living organisms is a technological challenge, not a physical impossibility.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

photo { Violet Forest }

science, time | September 5th, 2011 3:04 pm

According to a new study on tiny shrimp (Artemia franciscana), sex with partners from a different time could kill you.

Researchers at the Center for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE) in Montpellier, France, collected preserved brine shrimp eggs from various generations, and then reanimated them with water. Nicolas Rode and colleagues mated pairs of brine shrimp that had been reanimated from eggs preserved since 1985, 1996 and 2007, a period representing roughly 160 generations. They found that females that mated with males from the past or future died off sooner than those that mated with their own generation. The longer the time-shift, the earlier they died.

{ PopSci | Continue reading }

science, sex-oriented, time | August 4th, 2011 3:31 pm

science, time | July 27th, 2011 6:01 pm

At some point, the Mongol military leader Kublai Khan (1215–1294) realized that his empire had grown so vast that he would never be able to see what it contained. To remedy this, he commissioned emissaries to travel to the empire’s distant reaches and convey back news of what he owned. Since his messengers returned with information from different distances and traveled at different rates (depending on weather, conflicts, and their fitness), the messages arrived at different times. Although no historians have addressed this issue, I imagine that the Great Khan was constantly forced to solve the same problem a human brain has to solve: what events in the empire occurred in which order?

Your brain, after all, is encased in darkness and silence in the vault of the skull. Its only contact with the outside world is via the electrical signals exiting and entering along the super-highways of nerve bundles. Because different types of sensory information (hearing, seeing, touch, and so on) are processed at different speeds by different neural architectures, your brain faces an enormous challenge: what is the best story that can be constructed about the outside world?

The days of thinking of time as a river—evenly flowing, always advancing—are over. Time perception, just like vision, is a construction of the brain and is shockingly easy to manipulate experimentally. We all know about optical illusions, in which things appear different from how they really are; less well known is the world of temporal illusions. When you begin to look for temporal illusions, they appear everywhere.

{ David M. Eagleman/Edge | Continue reading }

photos { Henri Cartier-Bresson | Ruben Natal-San Miguel }

archives, brain, halves-pairs, photogs, time | June 27th, 2011 1:54 pm

An Amazonian tribe has no abstract concept of time, say researchers.

The Amondawa lacks the linguistic structures that relate time and space - as in our idea of, for example, “working through the night.”

The study, in Language and Cognition, shows that while the Amondawa recognize events occuring in time, it does not exist as a separate concept. (…)

“We’re really not saying these are a ‘people without time’ or ‘outside time’,” said Chris Sinha, a professor of psychology of language at the University of Portsmouth.

“Amondawa people, like any other people, can talk about events and sequences of events. What we don’t find is a notion of time as being independent of the events which are occuring; they don’t have a notion of time which is something the events occur in.”

The Amondawa language has no word for “time,” or indeed of time periods such as “month” or “year.”

The people do not refer to their ages, but rather assume different names in different stages of their lives or as they achieve different status within the community.

But perhaps most surprising is the team’s suggestion that there is no “mapping” between concepts of time passage and movement through space.

Ideas such as an event having “passed” or being “well ahead” of another are familiar from many languages, forming the basis of what is known as the “mapping hypothesis.” But in Amondawa, no such constructs exist.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

Linguistics, time | May 23rd, 2011 6:01 pm

There are (at least) two ways to implement a (Star Trek style) transporter:

1. A space-time wormhole takes you “directly” from here to there, or

2. We scan you, send the info, make a new copy at the other end, and destroy the original.

Some people care greatly about transporter type; they’d pay to use type #1, but pay greatly to avoid using type #2. But regardless of the morality of a type #2 transporter, I’m pretty confident that if cheap type #2 transporters were available, but not type #1, many people would use them often. (…)

A similar relation applies to two types of super-watches. (…) Here are the two ways to make super-watches:

1. Time Machine + Memory Wipe: The second time you push the button you enter a time machine that brings you back to soon after the moment you first pushed the button, displaced by a few feet. It also erases all memories you might have acquired since the first time you pushed the button. And no, you can’t bring anything else with you in the time machine.

2. Limited Time Copier: When you turn on the watch it makes an exact copy of you and puts that copy a few feet away. When you turn the watch off, or it automatically turns off, you are destroyed.

{ Overcoming Bias | Continue reading }

ideas, time | May 2nd, 2011 6:57 pm

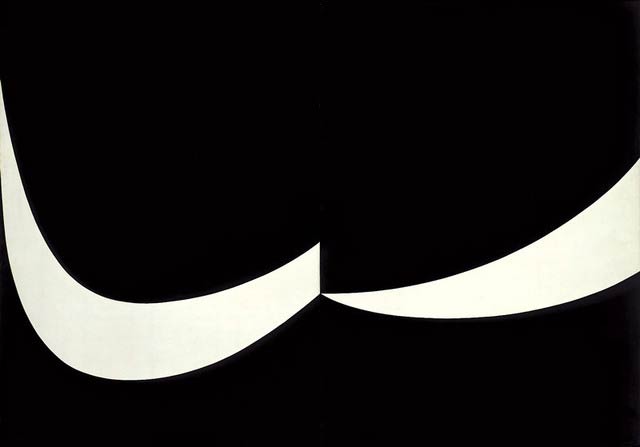

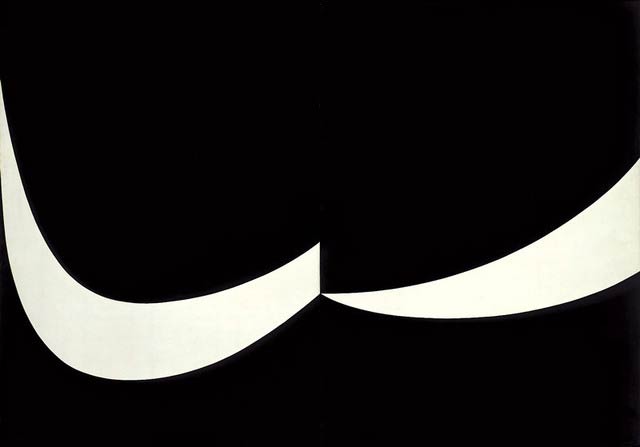

People who are more aware of their own heart-beat have superior time perception skills.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

artwork { Ellsworth Kelly, Atlantic, 1956 | Oil on canvas on two panels }

Ellsworth Kelly, science, time | April 23rd, 2011 7:25 pm

Eagleman has collected hundreds of stories like his, and they almost all share the same quality: in life-threatening situations, time seems to slow down. (…)

Eagleman is thirty-nine now and an assistant professor of neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston. (…)

The brain is a remarkably capable chronometer for most purposes. It can track seconds, minutes, days, and weeks, set off alarms in the morning, at bedtime, on birthdays and anniversaries. Timing is so essential to our survival that it may be the most finely tuned of our senses. In lab tests, people can distinguish between sounds as little as five milliseconds apart, and our involuntary timing is even quicker. If you’re hiking through a jungle and a tiger growls in the underbrush, your brain will instantly home in on the sound by comparing when it reached each of your ears, and triangulating between the three points. The difference can be as little as nine-millionths of a second.

Yet “brain time,” as Eagleman calls it, is intrinsically subjective. “Try this exercise,” he suggests in a recent essay. “Put this book down and go look in a mirror. Now move your eyes back and forth, so that you’re looking at your left eye, then at your right eye, then at your left eye again. When your eyes shift from one position to the other, they take time to move and land on the other location. But here’s the kicker: you never see your eyes move.” There’s no evidence of any gaps in your perception—no darkened stretches like bits of blank film—yet much of what you see has been edited out. Your brain has taken a complicated scene of eyes darting back and forth and recut it as a simple one: your eyes stare straight ahead. Where did the missing moments go?

The question raises a fundamental issue of consciousness: how much of what we perceive exists outside of us and how much is a product of our minds?

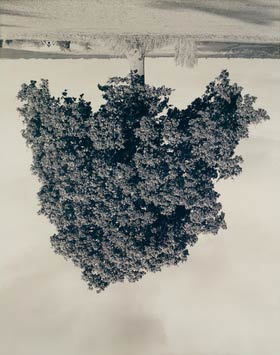

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

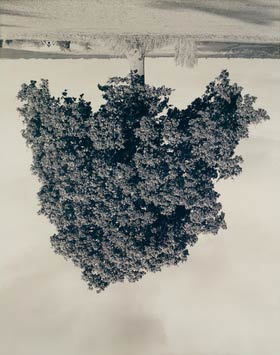

photo { Rodney Graham }

neurosciences, time | April 18th, 2011 7:00 pm