science

In December last year, a new research paper revealed how a protein called perforin – the ‘bullet’ of the immune system – kills rogue cells in our body.

How these immune pore-forming proteins function has been a key question since the discovery of “haemolytic complement proteins” in the 1890s by the Nobel laureate Jules Bordet. Bordet was the first to notice that the human immune system was capable of punching holes in target cells.

But as Professor Joe Trapani, head of the Cancer Immunology Program at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and one of the authors of the paper, says, “Until now, perforin has been a real black box. No-one has really known how it all fits together to form a pore”.

{ Wellcome Trust | Continue reading }

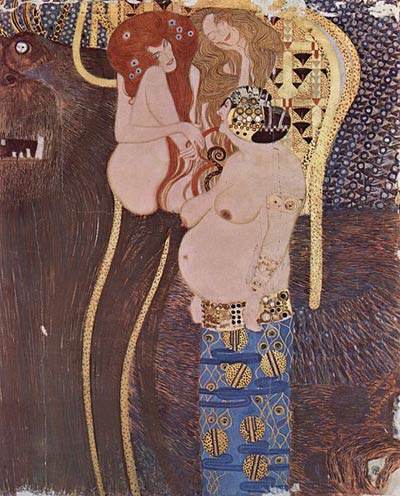

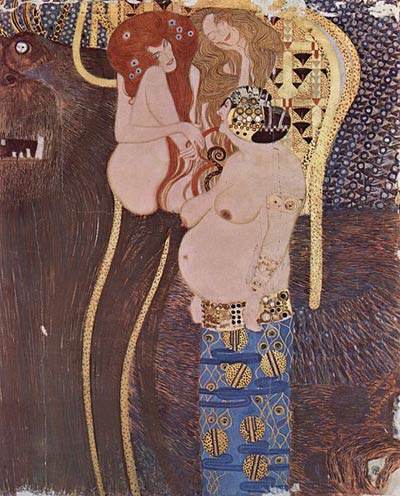

painting { Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze, 1902 }

science | February 14th, 2011 4:02 pm

Women tend to be better than men at reading other people’s subtle facial cues, especially cues from the eyes. Because of the gender difference in cognitive empathy – the ability to notice and correctly interpret body language – psychobiologists have hypothesized that testosterone levels could play a role in “mind reading” ability, or lack thereof.

A new study in PNAS validates this hypothesis by demonstrating that a dose of testosterone can make women lose some of their cognitive empathy.

{ ICHS | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships, science | February 10th, 2011 7:30 pm

We perceive our own bodies in many different ways. We can look at our bodies, feel touch on our bodies, and also feel our body from within, as when we experience our hearts racing or butterflies in our stomachs. One way to check how good people are at perceiving their body from within is to ask them to count their heartbeats over a few seconds, but without taking their own pulse. Neuroscientists believe that the more accurate people are at this task, the better their perception of internal bodily states is. Can our ability to detect our own heartbeat tell us something about our body-image, that is, the conscious and mainly visual representation of how our body looks like?

To answer this question, we, first, measured how good people are at feeling their body from within, using the heartbeat counting task. We then measured how good people are at perceiving their own body-image from the outside, by using a procedure that tricks them into feeling that a fake, rubber hand is their own hand.

The less accurate people were in monitoring their heartbeat, the more they were influenced by the illusion. (…)

It seems that a stable perception of the body from the outside, what is known as “body image”, is partly based on our ability to accurately perceive our body from within, such as our heartbeat.

{ Body in Mind | Continue reading }

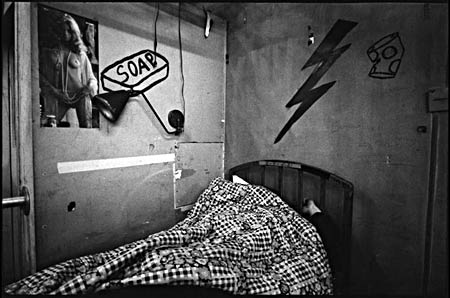

photo { Corrado Dalcò }

guide, science | February 10th, 2011 7:24 pm

Acoels, which are thought to be older than both Protostomes (mouth develops before the anus) and Deuterostomes (anus first). But now a team of evolutionary biologists is suggesting that Acoles belong within the group of Deuterostomes. This even though Acoles don’t have a separate mouth and anus at all, but an opening that serves both functions.

{ Pleiotropy | Continue reading }

science | February 10th, 2011 6:50 pm

The popular perception of the Dark Ages is wrong. That’s the message of Nancy Marie Brown’s “The Abacus and the Cross” (Basic Books), which tells the story of Gerbert of Aurillac (d. 1003), a monk who rose from humble beginnings to become Pope Sylvester II, and came to personify the union between science and religion that was in evidence a thousand years ago. “In his day, the earth was not [believed to be] flat. People were not terrified that the world would end at the stroke of midnight on December 31, 999. Christians did not believe Muslims and Jews were the devil’s spawn. [And] the Church was not anti-science—just the reverse,” writes Brown.

But in today’s world—in which religion and science are seen as being at odds with one another, it’s a challenge to orient oneself to the idea that the Church was a champion of learning. In the following Failure Interview, Brown introduces us to the so-called “Scientist Pope,” and explains why our beliefs about the Dark Ages are misguided.

{ Failure | Continue reading }

photo { Michel Delsol }

flashback, science | February 9th, 2011 5:06 pm

For someone who died at the age of 32 the largely self-taught Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan left behind an impressive legacy of insights into the theory of numbers—including many claims that he did not support with proof.

One of his more enigmatic statements, made nearly a century ago, about counting the number of ways in which a number can be expressed as a sum, has now helped researchers find unexpected fractal structures in the landscape of counting.

Ramanujan’s statement concerned the deceptively simple concept of partitions—the different ways in which a whole number can be subdivided into smaller numbers. Ken Ono of Emory University and his collaborators have now figured out new ways of counting all possible partitions, and found that the results form fractals—namely, structures in which patterns or shapes repeat identically at multiple different scales.

“The fractal theory we’ve discovered completely answers Ramanujan’s enigmatic statement,” Ono says. The problems his team cracked were seen as holy grails of number theory, and its solutions may have repercussions throughout mathematics.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

mathematics | February 9th, 2011 5:00 pm

Feelings of anxiety are normal and even desirable – they are part of what helps us survive in a world of real threats. But no less crucial is the return to normal – the slowing of the heartbeat and relaxation of tension – after the threat has passed. People who have a hard time “turning off” their stress response are candidates for post-traumatic stress syndrome, as well as anorexia, anxiety disorders and depression.

How does the body recover from responding to shock or acute stress? This question is at the heart of research conducted by Dr. Alon Chen of the Institute’s Neurobiology Department.

The response to stress begins in the brain, and Chen concentrates on a family of proteins that play a prominent role in regulating this mechanism. One protein in the family – CRF – is known to initiate a chain of events that occurs when we cope with pressure, and scientists have hypothesized that other members of the family are involved in shutting down that chain.

In research that appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Chen and his team have now, for the first time, provided sound evidence that three family members known as urocortin 1, 2 and 3 – are responsible for turning off the stress response.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

arwtork { Lucian Freud, Reflection with Two Children (Self-Portrait), 1965 | Freud painted this self-portrait by looking down at his reflection in a mirror placed by his feet; this accounts for the extreme foreshortening, and the halo-like ceiling light just above his left shoulder. The two children are Freud’s daughter and son, Rose and Ali Boyt. Freud said he used a palette knife to describe the space around him, smearing it on and smoothing its surface so that it seems like a strange, grey, voluminous void. | Tate }

brain, psychology, science | February 8th, 2011 9:44 pm

It’s been more than 10 years since it was noticed that certain enzymes – the sirtuins – had life-extending properties in organisms like yeast, and later nematodes, fruit flies, and mice. The excitement spread to other compounds, such as resveratrol, that seemed to activate or assist sirtuins. Hopes were high that such things might offer the known longevity benefits of calorie restriction in a pill form. Ever since then the gold rush has been on to figure out how these things work – and if possible, to be the first to market with the Fountain of Youth in a bottle. (…)

It’s pretty clear from this and many other studies that oxidative damage in cells is a cause of cell death and therefore of various health problems associated with aging. Undoubtedly there are a number of other factors that contribute to aging-related problems, such as cell death due to other causes and weakening or disregulation of the immune system. And even in the case of oxidative damage, there are many ways it can come about, and also many ways it might be inhibited. If you think of aging as a complex disease, like cancer – a point of view that has its detractors – then there are bound to be many causes and contributing factors. And also many ways to inhibit or arrest the process. The example considered here is just one of many.

{ Science and Reason | Continue reading }

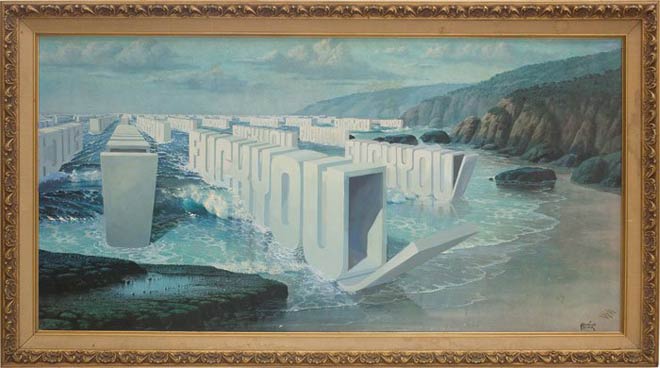

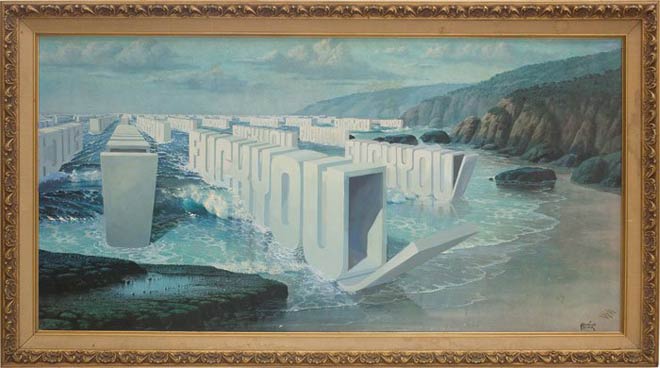

painting { Wayne White | Thanks Jared }

science | February 8th, 2011 8:55 pm

Can you take away the feelings of guilt through self harm? Well, here’s one way to find out.

Take 59 Australian students, and split them into three groups. Get two groups to write about something they did that they feel guilty about.

Then get one of those groups to stick their arms into iced water. The other group gets nice warm water. The third group writes about just some everyday interaction, but then they get the ice bath too.

When Brock Bastian, of the University of Queensland, and colleagues did that they found a couple of things. First the students who wrote about about a guilt-ridden experience really did feel more guilty.

Second, these guilt-ridden students kept their arms in the ice bath longer than the guilt-free students. What’s more, their level of guilt dropped more than the guilt-ridden students who had a warm water bath.

{ Epiphenom | Continue reading }

photo { Nikola Tamindzic }

related { Can one have pain and not know it? }

psychology | February 8th, 2011 8:40 pm

The human eye is an amazing piece of machinery. It can distinguish some ten million colours thanks to the remarkable light-sensitive rod and cone cells that populate the back of the eye.

These cells neatly divide up the process of vision. The rods, some 90 million of them, have a peak sensitivity to reddish light and work best in low light, providing our night vision.

The cones, on the other hand, some 5 million of them, come in three types. These are sensitive to long wavelengths (ie red), medium wavelengths (green) and short wavelengths (blue) producing colour vision. They are designated L, M and S cones respectively.

But here’s the puzzle: S cones are rare making up less than 10 per cent of the total. The L and M cones are much more common but their ratio can vary dramatically. People with otherwise normal colour vision can have L:M ratios of between 1:4 and 15:1.

(Other primates have different ratios although the ratio in new world monkeys is similar to ours.)

The question that leaves biologists scratching their heads is why.

One idea is that this distribution of cone cell types is the result of an adaptation to the environment in which the human eye evolved.

So if we can work out what that environment was like, we could get a handle on the forces that shaped our visual system.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

eyes, science | February 8th, 2011 8:20 pm

The problem is that glass breaks before it bends – even the tiniest fracture spreads rapidly in all directions until the entire pane shatters. In engineering terms, glass is strong (it can withstand a lot of stress before cracking) but not tough (it has little damage tolerance after the onset of cracking). This is in contrast to sheets of metal or plastic that can deform to accommodate small defects, making them generally tougher materials.

To a group of researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Caltech, this begged the question: is it possible to engineer tougher glass by making it behave more like metal? The answer, it turns out, is yes.

{ Berkeley Science Review | Continue reading }

photo { Maserati Quattroporte covered with 1,763 lbs of shattered glass by Luca Pancrazzi }

science, technology | February 8th, 2011 8:15 pm

Research has demonstrated that more than leaving you feeling rested, sleep actually improves your memory. Even better, a new study suggests that sleep actually helps you remember exactly what you need to remember.

{ ionpsych | Continue reading }

photo { Jill Freedman }

science, sleep | February 8th, 2011 7:06 pm

A giant net several kilometres in size has been built as part of a collaboration between Japan’s space agency and a 100-year-old fishing net company to collect debris from space.

Last year, a US report concluded that space was so littered with debris that a collision between satellites could set off an “uncontrolled chain reaction” capable of destroying the communications network on Earth. It is estimated there are 370,000 pieces of space junk.

The Japanese plan will see a satellite attached to a thin metal net spanning several kilometres launched into space. The net is then detached, and begins to orbit earth, sweeping up space waste in its path.

During its rubbish collecting journey, the net will become charged with electricity and eventually be drawn back towards earth by magnetic fields – before both the net and its contents burn upon entering the atmosphere.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading }

space, technology | February 7th, 2011 8:19 pm

Feelings, especially the kind that I call primordial feelings, portray the state of the body in our own brain. They serve notice that there is life inside the organism and they inform the brain (and its mind, of course), of whether such life is in balance or not. That feeling is the foundation of the edifice we call conscious mind. When the machinery that builds that foundation is disrupted by disease, the whole edifice collapses. Imagine pulling out the ground floor of a high-rise building and you get the picture. That is, by the way, precisely what happens in certain cases of coma or vegetative state.

Now, where in the brain is that “feel-making” machinery? It is located in the brain stem and it enjoys a privileged situation. It is part of the brain, of course, but it is so closely interconnected with the body that it is best seen as fused with the body. I suspect that one reason why our thoughts are felt comes from that obligatory fusion of body and brain at brain stem level.

{ Antonio Damasio/Wired | Continue reading }

Antonio Damasio is David Dornsife Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Southern California, where he heads USC’s Brain and Creativity Institute.

Damasio’s books deal with the relationship between emotions and feelings, and what their bases may be within the brain. His 1994 book, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain, is regarded as one of the most influential books of the past two decades.

In his third book, Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain, published in 2003, Damasio suggested that Spinoza’s thinking foreshadowed discoveries in biology and neuroscience views on the mind-body problem.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading | USC }

photo { Nathaniel Ward }

books, neurosciences, photogs, spinoza | February 7th, 2011 8:12 pm

Nasa has 18 facilities across the US, from Maryland to California, and its major contractors, companies such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin, have dozens more. But no place has assumed the identity of the country’s space programme quite like Brevard County. A mosquito-bitten slip of coast, 20 miles wide and 70 miles long, it was somewhere people used to drive through on their way to Palm Beach, until the US army decided to start testing its missiles there in October 1946.

And then, quite suddenly, it was colonised. The arrival of Wernher von Braun, designer of the V2 rocket, and the other founding fathers of the US space programme, made Brevard the fastest-growing county in America. Nasa, founded in 1958, built bridges and water systems, and when the space race reached its exorbitant heights in the mid-1960s, Brevard was the edge of the world. Astronauts raced their cars on the beach, newsmen camped out on their lawns and the county was given the dialling code 3-2-1 after the launch sequence. In 1973, Brevard put the Moon landing on its county seal.

The Apollo boom was followed by bust: 10,000 people lost their jobs when the programme was cancelled in 1972. But since then, Brevard has rebuilt itself around the space shuttle, Nasa’s longest-serving spacecraft and one of the most recognisable vehicles ever to fly. The parts may be manufactured elsewhere and its missions managed from Houston, but for the past three decades Brevard County and KSC have been, in Nasa-speak, where the rubber hits the road. The tourist-friendly launches and everlasting work of 132 missions have made the shuttle the central activity of America’s Space Coast—the stuff of daily life and conversation. (…)

Brevard hasn’t escaped the property crash. Property values in Brevard County have fallen by 45 per cent since 2007 and are still falling—more than 10 per cent last year. (…) Yet it is nothing compared to what is to come, because the rockets and the recession are about to collide. There will be at least two or maybe three missions this year: Discovery, planned for February; the official final flight, Endeavour, scheduled for 1st April; and possibly a “final final” mission if Atlantis gets the go-ahead, most likely in June. But at some point in 2011, the space shuttle will fly for the last time.

{ Prospect | Continue reading }

photo { Brian Ulrich }

U.S., economics, space | February 6th, 2011 8:01 pm

The idea that an individual has power over his health has a long history in American popular culture. The “mind cure” movements of the 1800s were based on the premise that we can control our well-being. In the middle of that century, Phineas Quimby, a philosopher and healer, popularized the view that illness was the product of mistaken beliefs, that it was possible to cure yourself by correcting your thoughts. Fifty years later, the New Thought movement, which the psychologist and philosopher William James called “the religion of the healthy minded,” expressed a very similar view: by focusing on positive thoughts and avoiding negative ones, people could banish illness.

The idea that people can control their own health has persisted through Norman Vincent Peale’s “Power of Positive Thinking,” in 1952, to a popular book today, “The Secret,” by Rhonda Byrne, which teaches that to achieve good health all we have to do is to direct our requests to the universe.

It’s true that in some respects we do have control over our health. By exercising, eating nutritious foods and not smoking, we reduce our risk of heart disease and cancer. But the belief that a fighting spirit helps us to recover from injury or illness goes beyond healthful behavior. It reflects the persistent view that personality or a way of thinking can raise or reduce the likelihood of illness.

The psychosomatic hypothesis, which was popular in the mid-20th century, held that repressed emotional conflict was at the core of many physical diseases: Hypertension was the product of the inability to deal with hostile impulses. Ulcers were caused by unresolved fear and resentment. And women with breast cancer were characterized as being sexually inhibited, masochistic and unable to deal with anger.

Although modern doctors have rejected those beliefs, in the past 20 years, the medical literature has increasingly included studies examining the possibility that positive characteristics like optimism, spirituality and being a compassionate person are associated with good health. And books on the health benefits of happiness and positive outlook continue to be best sellers.

But there’s no evidence to back up the idea that an upbeat attitude can prevent any illness or help someone recover from one more readily. On the contrary, a recently completed study of nearly 60,000 people in Finland and Sweden who were followed for almost 30 years found no significant association between personality traits and the likelihood of developing or surviving cancer. Cancer doesn’t care if we’re good or bad, virtuous or vicious, compassionate or inconsiderate. Neither does heart disease or AIDS or any other illness or injury.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

photo { David Maisel }

flashback, health, psychology | February 5th, 2011 9:33 pm

Have you ever watched a loved one stub their toe and wince yourself in sympathy? If so, you’ve perhaps unknowingly experienced a psychological phenomenon known as ‘embodied simulation’.

When you see someone making a gesture, be it emotional or physical, the regions activated in their brain are also activated in yours, creating a common network. Scientists think that this network is needed for effective communication of information.

What had not been shown before, however, was direct evidence of embodied simulation in between two people. A group of scientists, including Dr Nikolaus Weiskopf from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at UCL, have been working on this using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to directly investigate the workings of couple’s brains. […]

Analysis of the data showed that sending emotional information via facial expressions resulted in similar activity in both the sender’s and perceiver’s brains. Several brain areas showed common activity, suggesting that emotion-specific information is encoded by similar signals in both sender and perceiver. The results also showed that the part of the brain known to be activated when people fake an emotion in their facial expression, known as the ventral premotor cortex, was not activated during this experiment.

{ WellcomeTrust | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences, relationships | February 5th, 2011 9:10 pm

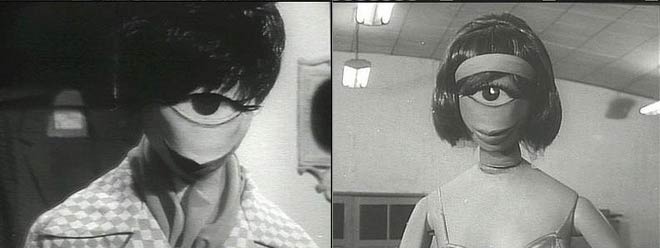

In the history of inkblots, the experiment of Hermann Rorschach [1884-1922] is the most famous moment: a controversial attempt to establish a scientific personality assessment based on ten standard Rorschach inkblots. Then comes Andy Warhol, who in the 1980s reconnects inkblots with the art that came before. He did these huge, very sexual, strange, hieratic paintings which he called ‘Rorschach Paintings’ - although they were, in fact, entirely of his own invention. At the opening a journalist asked him what they meant and Warhol - in that amazing, neutral, “I’m a mirror” way of his– said, “Oh, I made a mistake, I got that wrong. I thought the idea was that you make your own inkblots and the psychiatrist interprets them. If I’d known, I’d just have copied the originals!” (…)

there have been inkblot tests around for ages, but in the 19th century they took over from silhouettes as the parlour game, partly due to a German doctor and poet called Justinus Koerner, who was a friend of the German Romantics and was interested in the nascent science of psychology and such things. He’d write endless letters, and he doodled in them, and started playing around with inkblots. He was the one who worked out that you could make inkblots symmetrical by folding them over.

{ The Browser | Continue reading }

related { Rorschach Test – Psychodiagnostic Plates: The ten inkblots + Decryption }

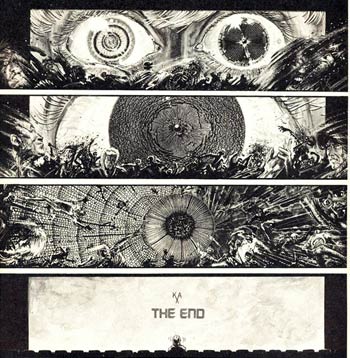

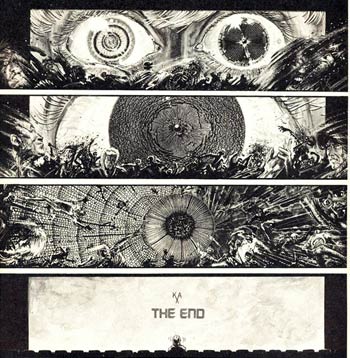

image { John Waters, Director’s cuts }

flashback, psychology, warhol | February 5th, 2011 8:26 pm

“Most thought is unconscious. It doesn’t work by mathematical logic. You can’t reason directly about the world—because you can only conceptual what your brain and body allow, and because ideas are structured using frames.” Lakoff says. “As Charles Fillmore has shown, all words are defined in terms of conceptual frames, not in terms of some putative objective, mind-free world.”

“People really reason using the logic of frames, metaphors, and narratives, and real decision making requires emotion, as Antonio Damasio showed in Descartes’ Error.” (…)

People Don’t Decide Using ‘Just the Facts’ (…)

Don’t Repeat the Language Politicians Use: Decode It

{ Explainer | Continue reading }

photo { Jessica Craig-Martin }

neurosciences, press | February 5th, 2011 8:20 pm

Michael Hartl says it’s time to lose pi in favor of a new symbol: tau. We asked him to explain why pi has to go.

Hartl is the author of The Tau Manifesto, which argues that, quite simply, pi is wrong. He’s also a physicist who has previously both studied and taught at Harvard and Caltech.

So what is tau? Well, simply enough, it’s 2*pi, or 2π.

{ io9 | Continue reading }

mathematics | February 3rd, 2011 5:45 pm