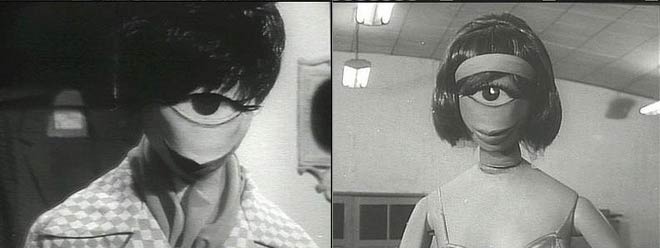

Gentil n’a qu’un oeil

The human eye is an amazing piece of machinery. It can distinguish some ten million colours thanks to the remarkable light-sensitive rod and cone cells that populate the back of the eye.

These cells neatly divide up the process of vision. The rods, some 90 million of them, have a peak sensitivity to reddish light and work best in low light, providing our night vision.

The cones, on the other hand, some 5 million of them, come in three types. These are sensitive to long wavelengths (ie red), medium wavelengths (green) and short wavelengths (blue) producing colour vision. They are designated L, M and S cones respectively.

But here’s the puzzle: S cones are rare making up less than 10 per cent of the total. The L and M cones are much more common but their ratio can vary dramatically. People with otherwise normal colour vision can have L:M ratios of between 1:4 and 15:1.

(Other primates have different ratios although the ratio in new world monkeys is similar to ours.)

The question that leaves biologists scratching their heads is why.

One idea is that this distribution of cone cell types is the result of an adaptation to the environment in which the human eye evolved.

So if we can work out what that environment was like, we could get a handle on the forces that shaped our visual system.