science

We often remember things by relying on the overall gist of an event—for example, instead of storing every detail about our last birthday, we tend to remember abstract things like “I had a fun party” or “I was in a grumpy mood because I felt old.”

This strategy allows us to remember more things about an event, but there’s one major drawback: by storing memories based on gist, we actually change how we remember the event. This happens because we are biased to remember things that are consistent with our overall summary of the event. So if we remember the birthday party was “super fun” overall, we’ll exaggerate how we remember the details—the average chocolate cake is now “insanely good”, and the 10 friends who were there becomes a “huge crowd.” (…)

As it turns out, gist changes the way we remember an event after just one second.

{ I on Psych | Continue reading }

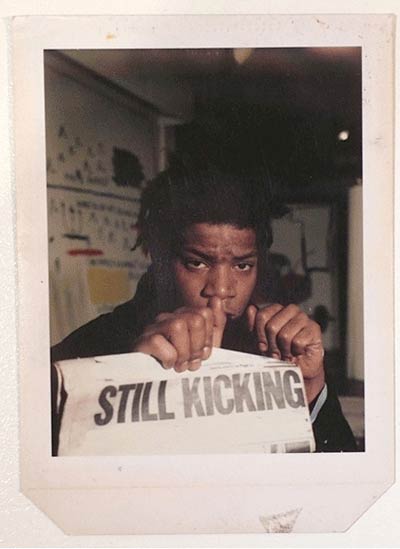

photo { Noah Kalina }

memory, neurosciences | April 8th, 2011 4:15 pm

Science is not always about success. Most research projects are unsuccessful stories producing ambiguous or ‘null’-results that don’t lead to unambiguous conclusion. Nevertheless this ‘failed’ research provides useful and valuable information for fellow scientists. Currently only research projects with positive results and clear conclusions have the chance to get published in scientific journals. Due to these publication practices a lot information is lost for the scientific community and additionally scientists find themselves in the dilemma of having to overinterpret data.

We have set out to change this. With the Journal of Unsolved Questions (JUnQ) we provide a means to gather ‘null’-result research and open problems.

{ JUnQ.info | Continue reading }

ideas, science | April 8th, 2011 4:00 pm

“Red, ‘bloodshot’ eyes are prominent in medical diagnoses and in folk culture”, said lead author Dr. Robert R. Provine from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “We wanted to know if they influence the everyday behaviour and attitudes of those who view them, and if they trigger perceptions of attractiveness.”

Research published in Ethology finds that people with bloodshot eyes are considered sadder, unhealthier and less attractive than people whose eye whites are untinted, a cue which is uniquely human. (…)

“Standards of beauty vary across cultures, however, youth and healthiness are always in fashion because they are associated with reproductive fitness,” said Provine. “Traits such as long, lustrous hair and smooth or scar-free skin are cues of youth and offer the beholder a partial record of health.

Now clear eye whites join these traits as a universal standard for the perception of beauty and a cue of health and reproductive fitness. Given this discovery, eye drops that ‘get the red out’ can be considered beauty aids.”

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

eyes, psychology, science | April 8th, 2011 11:11 am

A new exciting paper in the forthcoming Journal of Consumer Psychology makes the case that money should buy us happiness, but most people aren’t spending it right. On the edge of psychology and economics, Profs. Daniel Gilbert, Elizabeth Dunn and Timothy Wilson lay out eight principles of spending efficiently, including:

1) Buy more experiences and fewer objects.

2) Don’t worry about insurance.

3) The frequency of happy events matters more than their intensity.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

photo { Pieter Hugo }

economics, guide, psychology | April 7th, 2011 11:46 am

The process of development is an astounding journey from simplicity to complexity. You start with a single cell, the fertilized egg, and you end up with a complete multicellular organism, made up of tissues that self-organize from many individual cells of different types. The question of how cells know who to be and where to go has many layers to it, starting with the question of how you lay down the basic body plan (head here, tail there, which side is left and where does the heart go?) and continuing on down to microscopic structures, with questions such as how and where to form the small tubes that will allow blood to permeate through apparently solid tissues. This kind of self-organizing behavior is deeply interesting to robotics researchers (who would love to copy it) and tissue engineers (who would like to manipulate it).

A recent paper (Parsa et al. 2011. Uncovering the behaviors of individual cells within a multicellular microvascular community) takes a close look at self-organization on the micro level. (…)

Despite the tremendous variability in the paths followed by individual cells, the authors hoped to find patterns in their data that might provide insight into how the network forms. And luckily, the patterns were there to find. Using a clustering algorithm, they identified groups of cells that behaved similarly to each other with respect to specific sets of behavioral parameters. For example, looking at the pattern of how the area of a cell grows and shrinks allowed the authors to define three major clusters of cells that accounted for about 2/3 of the cells in their study. In the same way, they could define subsets of cells that moved through the gel in similar ways. Although these clusters are rather broadly defined, they seem to be telling us something important about differences between the cells in the different subsets; the subset of cells that spread early (with areas showing a peak at 60 or 120 minutes) are more likely to end up as connection points in the network, while the cells that spread late (300 minutes) tend to end up as branches between the connection points.

{ It takes 30 | Continue reading }

photo { Charlie Engman }

mystery and paranormal, science | April 6th, 2011 6:06 pm

In philosophy of mind, a “cerebroscope” is a fictitious device, a brain–computer interface in today’s language, which reads out the content of somebody’s brain. An autocerebroscope is a device applied to one’s own brain. You would be able to see your own brain in action, observing the fleeting bioelectric activity of all its nerve cells and thus of your own conscious mind. There is a strange loopiness about this idea. The mind observing its own brain gives rise to the very mind observing this brain. How will this weirdness affect the brain? Neuroscience has answered this question more quickly than many thought possible.

But first, a bit of background. Epileptic seizures—hypersynchronized, self-maintained neural discharges that can sometimes engulf the entire brain—are a common neurological disorder. These recurring and episodic brain spasms are kept in check with drugs that dampen excitation and boost inhibition in the underlying circuits. Medication does not always work, however. When a localized abnormality, such as scar tissue or developmental miswiring, is suspected of triggering the seizure, neurosurgeons may remove the offending tissue. (…)

Under Fried’s supervision, a group from my laboratory—Rodrigo Quian Quiroga, Gabriel Kreiman and Leila Reddy—discovered a remarkable set of neurons in the jungles of the medial temporal lobe, the source of many epileptic seizures. This region, deep inside the brain, which includes the hippocampus, turns visual and other sensory percepts into memories.

We enlisted the help of several epileptic patients. While they waited for their seizures, we showed them about 100 pictures of familiar people, animals, landmark buildings and objects. We hoped one or more of the photographs would prompt some of the monitored neurons to fire a burst of action potentials. Most of the time the search turned up empty-handed, although sometimes we would come upon neurons that responded to categories of objects, such as animals, outdoor scenes or faces in general. But a few neurons were much more discerning. One hippocampal neuron responded only to photos of actress Jennifer Aniston but not to pictures of other blonde women or actresses; moreover, the cell fired in response to seven very different pictures of Jennifer Aniston. (…)

Nobody is born with cells selective for Jennifer Aniston. (…) The networks in the medial temporal lobe recognize such repeating patterns and dedicate specific neurons to them. You have concept neurons that encode family members, pets, friends, co-workers, the politicians you watch on TV, your laptop, that painting you adore.

Conversely, you do not have concept cells for things you rarely encounter.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

ideas, neurosciences | April 6th, 2011 6:00 pm

In a closely-watched oral argument Monday at a federal courthouse in Washington, the core questions of the case read like scripts from a college philosophy exam: are isolated human genes and the subsequent comparisons of their sequences patentable? Can one company own a monopoly on such genes without violating the rights of others? They are multi-billion dollar questions, the judicially-sanctioned answers to which will have enormous ramifications for the worlds of medicine, science, law, business, politics and religion.

Even the name of the case at the U.S. Circuit Court for the Federal Circuit — Association of Molecular Pathology, et al. v United States Patent and Trademark Office, et al — oozes significance. The appeals court judges have been asked to determine whether seven existing patents covering two genes — BRCA1 and BRCA2 (a/k/a “Breast Cancer Susceptibility Genes 1 and 2″) — are valid under federal law or, instead, fall under statutory exceptions that preclude from patentability what the law identifies as ”products of nature.”

In other words, no one can patent a human being. Not yet anyway.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

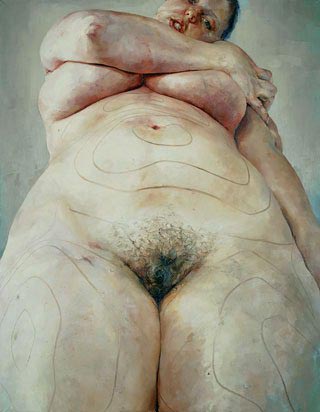

painting { Jenny Saville, Plan, 1993 }

economics, genes, law | April 6th, 2011 5:51 pm

An examination of emotions reported on 12 million personal blogs along with a series of surveys and laboratory experiments shows that the meaning of happiness is not fixed; instead, it systematically shifts over the course of one’s lifetime. Whereas younger people are more likely to associate happiness with excitement, as they get older, they become more likely to associate happiness with peacefulness. This change appears to be driven by a redirection of attention from the future to the present as people age. The dynamic of what happiness means has broad implications, from purchasing behavior to ways to increase one’s happiness.

{ The Shifting Meaning of Happiness/SAGE | Continue reading }

photo { Rachel Styer }

psychology | April 5th, 2011 5:17 pm

The principle of Feng shui - to arrange rooms and buildings in ways that are pleasing and health-giving - has popular appeal. Unfortunately, Feng shui’s scientific credentials are lacking, being based as it is on the ancient Chinese concept of Ch’i or life-force. The good news is that psychologically informed, evidence-based design is on the increase. Consider this new study by Sibel Dazhir and Marilyn Read, which has compared the effects of curvilinear (rounded) and rectilinear (straight-edged) furniture on people’s emotions. (…)

The two room versions full of curvilinear furniture provoked significantly higher pleasure and approach ratings from the students. (…) It’s worth considering whether rectilinear-themed rooms may have their own benefits for purposes other than relaxing and socializing.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

interior { Chad McPhail }

guide, psychology, visual design | April 4th, 2011 4:00 pm

If you can be sure of one thing, then surely it is that you exist. Even if the world were a dream or a hallucination, it would still need you to be dreaming or hallucinating it. (…)

There is a wide range of scientific evidence that is used to deny “I think, therefore I am”. In René Descartes’ famous deduction, a coherent, structured experience of the world is inextricably linked with a sense of a self at the heart of it. But as the clinical neuropsychologist Paul Broks explained to me, we now know the two can in fact be separated.

People with Cotard’s syndrome, for instance, can think that they don’t exist, an impossibility for Descartes. Broks describes it as a kind of “nihilistic delusion” in which they “have no sense of being alive in the moment, but they’ll give you their life history”. They think, but they do not have sense that therefore they are.

Then there is temporal lobe epilepsy, which can give sufferers an experience called transient epileptic amnesia. “The world around them stays just as real and vivid – in fact, even more vivid sometimes – but they have no sense of who they are,” Broks explains. This reminds me of Georg Lichtenberg’s correction of Descartes, who he claims was entitled to deduce from “I think” only the conclusion that “there is thought”. This is precisely how it can seem to people with temporal lobe epilepsy: there is thought, but they have no idea whose thought it is.

{ The Independent | Continue reading }

photo { Noritoshi Hirakawa }

ideas, psychology | April 2nd, 2011 1:57 pm

Waiting is the period we endure until the expected happens. We wait for all sorts of things: the bus, dinner, colleagues who are late for a meeting, the rain to stop, etc. Waiting is built into our social lives. And our waiting behavior is influenced by a fair number of variables. There isn’t a prescribed method for waiting, and yet waiting in certain contexts tends toward a similar pattern of group impatience leading to aggressive strategies that are meant to better position the waiting individual for the event.

It may be that people are responding to a need to defend their territory. Territories are defined as areas that are controlled through established boundaries that are defended as necessary. There are private and public territories. Homes are private territories that are largely controlled by residents with little to no challenge for ownership from outside parties. However public territories, such as waiting rooms and phone booths, are temporary territories where “ownership” or residence may be challenged simply by the presence of others.

Researchers Ruback, Pape, and Doriot report that traditionally people appear to leave an area more quickly when the space around them has been “invaded.” For example, people tend to cross the street faster when grouped with strangers (perhaps this explains New Yorkers’ tendency for speed walking?), and researchers have found that library patrons will change seats or leave if strangers sit at the same table.

{ Anthropology in Practice | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | March 30th, 2011 7:29 pm

Many people like mathematics because it gives definite answers. Things are either true or false, and true things seem true in a very fundamental way.

The fact is, however, that mathematics has been moving on somewhat shaky philosophical ground for some time now. With the work of the logician Kurt Gödel and others in the 1930s it became clear that there are limits to the power of mathematics to pin down truth. In fact, it’s possible to build different versions of mathematics in which certain statements are true or false depending on your preference. This raises the possibility that mathematics is little more than a game in which we choose the rules to suit our purpose.

{ Plus mag | Continue reading }

related { Researchers have found a fractal pattern underlying everyday math. In the process, they’ve discovered a way to calculate partition numbers, a challenge that’s stymied mathematicians for centuries. | Wired | full story }

ideas, mathematics | March 30th, 2011 7:29 pm

One of the mysteries of human behavior is why we sometimes act with completely selfless altruism. When asked to play totally anonymous games in which we can cheat without anyone else ever finding out, very often we don’t.

Instead, we play the game fairly, which results in a cost to ourselves (compared with what we could’ve had) and a benefit to the stranger. That’s a mystery because evolution says that organisms which don’t act to maximize benefit to themselves - whatever the cost to others - should die out.

Several explanations have been put forward, but one of the most intriguing stems from the fact that we live in social networks. In a network like this, we depend critically on the kindness of others.

A new study has looked at how altruistic behavior can be transmitted between players in the kinds of anonymous games that social psychologists are so fond of.

What they found was that the amount individuals contributed in one round was affected by how generous their partners were in previous rounds. If they played with generous people in round 1, then they would be more generous to the new partners they had in round 2. In fact, they showed that this effect was propagated through new partners.

Unselfish acts propagated out to 3 degrees of separation. When you remember that only 6 degrees of separation stand between you and every other person on the planet, you can understand how powerful and important this effect is.

{ Epiphenom | Continue reading }

Most people with an interest in evolution understand why selfish genes do not mean selfish individuals. It’s clear that selfish genes will benefit from co-operation (you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours, also known as reciprocity), and kin selection (as the biologist JBS Haldane famously put it, “I would lay down my life for two brothers or eight cousins”).

What most people may not know (I certainly didn’t before reading West’s article) is that these, in fact, are the sole genetic basis for altruism. But if that’s the case, how do you get from here to the apparently completely selfless altruism sometimes seen in humans?

Reciprocity doesn’t need to be direct to be effective. If, by sharing with you I help to set up a virtuous circle, that will likely result in some benefit to me down the line. This has been seen in practice, with virtuous deeds propagating out to at least three degrees of separation.

{ Epiphenom | Continue reading }

photo { Noah Kalina }

psychology, relationships | March 30th, 2011 7:00 pm

Magnetism remains the most developed way to store digital information. The giga and terabytes of computer hard drives as well as the magnetic stripes that still are used for credit cards or hotel room keys, all function with the help of magnetic fields. There, the direction of the magnetic fields, up or down, expresses the digital 0s and 1s that make up the computer bits and bytes.

As the amount of data we store on hard drives continues to increase, it is of course desirable that read and write speeds follow that trend. (…)

In a paper published in advance on the Nature website this week, Ilie Radu, Theo Rasing from Radboud University in Nijmegen and others have investigated the details of the optical switching proceeds for a particular class of magnets, antiferromagnets.

{ All that matters | Continue reading }

photo { James Bond’s Rolex activates a “Hyper intensified magnetic field” “powerful enough to even deflect the path of a bullet at long range in Live and Let Die, 1971 }

science, technology | March 30th, 2011 6:59 pm

Why is aspirin toxic to cats?

One animal’s cure can be another animal’s poison. Take aspirin – it’s one of the most popular drugs on the market and we readily use it as a painkiller. But cats are extremely sensitive to aspirin, and even a single extra-strength pill can trigger a fatal overdose. Vets will sometimes prescribe aspirin to cats but only under very controlled doses.

The problem is that cats can’t break down the drug effectively. They take a long time to clear it from their bodies, so it’s easy for them to build up harmful concentrations. This defect is unusual – humans clearly don’t suffer from it, and neither do dogs. All cats, however, seem to share the same problem, from house tabbies to African lions.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

The term big cat – which is not a biological classification – is used informally to distinguish the larger felid species from smaller ones. One definition of “big cat” includes the four members of the genus Panthera: the tiger, lion, jaguar, and leopard. Members of this genus are the only cats able to roar. A more expansive definition of “big cat” also includes the cheetah, snow leopard, clouded leopard, and cougar.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

animals, cats, drugs, health, science | March 29th, 2011 7:27 pm

A little more than 40 years ago, a partially functioning brain would not have gotten in the way of organ donation; irreversible cardiopulmonary failure was still the only standard for determining death. But during the 1970s, that began to change, and by the early 1980s, the cessation of all brain activity — brain death — had become a widely accepted standard. In the transplant community, brain death was attractive for one particular reason: The bodies of such donors could remain on respirators to keep their organs healthy, even during much of the organ-removal surgery.

Today, the medical establishment, facing a huge shortage of organs, needs new sources for transplantation. One solution has been a return to procuring organs from patients who die of heart failure. Before dying, these patients are likely to have been in a coma, sustained by a ventilator, with very minimal brain function — a hopeless distance from what we mean by consciousness. Still, many people, including some physicians, consider this type of organ donation, known as “donation after cardiac death” or DCD, as akin to murder.

Critics of DCD contend that some patients may still be alive five or even 10 minutes after cardiac arrest because, theoretically, their hearts could be restarted, and some of their brain function might still remain. In such cases, critics assert, the patients were clearly not dead because their condition was reversible. Advocates of DCD counter that do-not-resuscitate orders from a patient or family render the argument about irreversibility moot.

In any case, there would be little debate about DCD if organs in a body remained viable for transplantation 20 or 30 minutes after heart and lung failure. But they become damaged quickly, so surgeons have to act fast — ideally, within about 10 minutes of cardiac arrest.

According to the Uniform Determination of Death Act, which was drafted about 30 years ago and has since been adopted, in some form, by all of the states, you can be declared dead in one of two ways: Your brain can irreversibly cease functioning, or your heart and lungs can irreversibly stop working. “Irreversibly,” in this context, has fueled the controversy. Does it mean the heart is unable to spontaneously start by itself? Or does it mean that even resuscitation efforts fail to restart the heart? (…)

More than 100,000 potential organ recipients idle on the waiting list maintained by the United Network for Organ Sharing, which manages the U.S. transplant system. An average of 18 people on the list die each day because of a shortage of donor organs.

{ Stanford Medicine | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Frank, London, 1952 }

health, science | March 29th, 2011 7:00 pm

For 40 years, psychologists thought that humans and animals kept time with a biological version of a stopwatch. Somewhere in the brain, a regular series of pulses was being generated. When the brain needed to time some event, a gate opened and the pulses moved into some kind of counting device.

One reason this clock model was so compelling: Psychologists could use it to explain how our perception of time changes. Think about how your feeling of time slows down as you see a car crash on the road ahead, how it speeds up when you’re wheeling around a dance floor in love. Psychologists argued that these experiences tweaked the pulse generator, speeding up the flow of pulses or slowing it down.

But the fact is that the biology of the brain just doesn’t work like the clocks we’re familiar with. Neurons can do a good job of producing a steady series of pulses. They don’t have what it takes to count pulses accurately for seconds or minutes or more. The mistakes we make in telling time also raise doubts about the clock models. If our brains really did work that way, we ought to do a better job of estimating long periods of time than short ones. Any individual pulse from the hypothetical clock would be a little bit slow or fast. Over a short time, the brain would accumulate just a few pulses, and so the error could be significant. The many pulses that pile up over long stretches of time should cancel their errors out. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. As we estimate longer stretches of time, the range of errors gets bigger as well.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

neurosciences, time | March 28th, 2011 5:48 pm

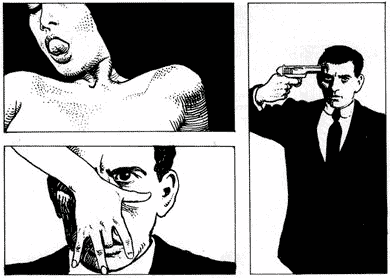

The ‘Regrets of the Typical American’ have been analysed in a new study that not only looks at what US citizens regret most, but provides some clues for those wanting to know whether it is better to regret something you haven’t done, or regret something you have. (…)

Women, who tend to value social relationships more than men, have more regrets of love (romance, family) compared to men. Conversely, men were more likely to have work-related (career, education) regrets. Those who lack either higher education or a romantic relationship hold the most regrets in precisely these areas.

The study also found that regrets about things you haven’t done were equally as common as regrets about things you have, no matter how old the person.

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading + Chart }

strip { Milo Manara }

unrelated { Envy is a stronger motivator than admiration, according to a new study }

psychology | March 28th, 2011 5:25 pm

The most familiar domain, though arguably not the most important to the Earth’s overall biosphere, is the eukaryotes. These are the animals, the plants, the fungi and also a host of single-celled creatures, all of which have complex cell nuclei divided into linear chromosomes.

Then there are the bacteria—familiar as agents of disease, but actually ecologically crucial. Some feed on dead organic matter. Some oxidise minerals. And some photosynthesise, providing a significant fraction (around a quarter) of the world’s oxygen. Bacteria, rather than having complex nuclei, carry their genes on simple rings of DNA which float around inside their cells.

The third great domain of life, the archaea, look, under a microscope, like bacteria. For that reason, their distinctiveness was recognised only in the 1970s. Their biochemistry, however, is very different from that of bacteria (they are, for example, the only organisms that give off methane as a waste product), and their separate history seems to stretch back billions of years.

But is that it? Or are there other biological domains hiding in the shadows—missed, like the archaea were for so long, because biologists have been using the wrong tools to look? A paper published in the Public Library of Science suggests there might indeed be at least one other, previously hidden, domain of life.

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

mystery and paranormal, science | March 27th, 2011 5:00 pm

Dendrology, visual design | March 27th, 2011 5:00 pm