science

It’s email, it’s the Internet, it’s video games, then when texting comes along, it’s texting, and when social networking comes along, it’s social networking. So whatever the flavor of the month in terms of new technologies are, there’s research that comes out very quickly that shows how it causes our children to be asocial, distracted, bad in school, to have learning disorders, a whole litany of things.

And then the Pew Foundation and MacArthur Foundation started saying, about three or four years ago: “Wait, let’s not assume these things are hurting our kids. Let’s just look at how our kids are using media and stop with testing that’s set up from a pejorative or harmful point of view.” (…)

The phenomenon of attention blindness is real — when we pay attention to one thing, it means we’re not paying attention to something else. When we’re multitasking, what we’re actually really doing is what Linda Stone calls “continuous partial attention.” We’re not actually simultaneously paying equal attention to two things: One of the things that we’re doing is probably being done automatically, and we’re sort of cruising through that, and we’re paying more attention to the other thing. Or we’re moving back and forth between them. But any moment when there is a major new form of technology, people think it’s going to overwhelm the brain. In the 1930s there was legislation introduced to prevent Motorola from putting radios in dashboards, because it was thought that people couldn’t possibly cope with driving and listening to the radio. (…)

We used to think that as we get older we develop more neural pathways, but the opposite is actually the case. You and I have about 40 percent less neurons than a newborn infant does. (…) They are learning to process that kind of information faster. That which we experience shapes our pathways, so they’re going to be far less stressed by a certain kind of multitasking that you are or than I am, or people who may not have grown up with that.

{ Interview with Cathy N. Davidson | Salon | Continue reading }

illustration { Geneviève Gauckler }

brain, kids, technology | August 29th, 2011 2:57 pm

8.7 million. That is a new, estimated total number of species on Earth — the most precise calculation ever offered — with 6.5 million species found on land and 2.2 million (about 25 percent of the total) dwelling in the ocean depths.

Until now, the number of species on Earth was said to fall somewhere between 3 million and 100 million.

Furthermore, the study, published today by PLoS Biology, says a staggering 86% of all species on land and 91% of those in the seas have yet to be discovered, described and catalogued.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

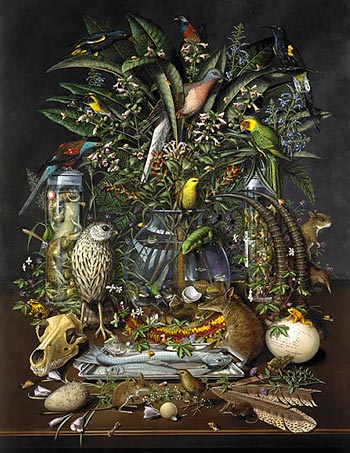

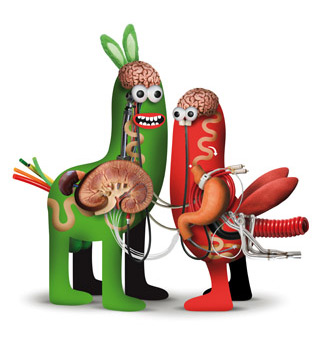

painting { Isabella Kirkland }

animals, science | August 28th, 2011 9:05 am

If you live on a country road you can say hello to each of the occasional persons who passes by: but obviously you can’t do this on Fifth Avenue.

As a measure of social involvemcnt for instance, we are now studying thc rcsponse to a lost child in big city and small town. A child of nine asks people to help him call his home. The graduate students report a strong difference between city and town dwellers: in the city, many more people refused to extend help to the nine-year-old. I like thc problem because there is no more meaningful measure of the quality of a culture than the manner in which it treats its children.

{ Conversation with Stanley Milgram, Psychology Today, 1974 | Continue reading | PDF }

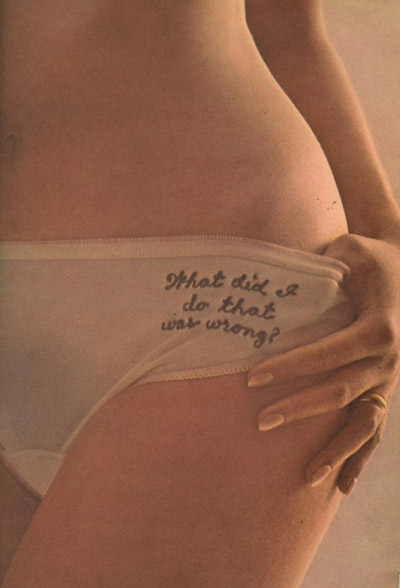

photo { Helen Levitt, New York, c. 1940 }

kids, psychology | August 28th, 2011 9:04 am

The practice of naming storms (tropical cyclones) began years ago in order to help in the quick identification of storms in warning messages because names are presumed to be far easier to remember than numbers and technical terms. (…)

In the beginning, storms were named arbitrarily. An Atlantic storm that ripped off the mast of a boat named Antje became known as Antje’s hurricane. Then the mid-1900’s saw the start of the practice of using feminine names for storms.

In the pursuit of a more organized and efficient naming system, meteorologists later decided to identify storms using names from a list arranged alpabetically. Thus, a storm with a name which begins with A, like Anne, would be the first storm to occur in the year.

Before the end of the 1900’s, forecasters started using male names for those forming in the Southern Hemisphere. (…)

Since 1953, Atlantic tropical storms have been named from lists originated by the National Hurricane Center. (…) Six lists are used in rotation. Thus, the 2008 list will be used again in 2014.

{ World Meteorological Organization | Continue reading }

related { This isn’t the first time we’ve met Hurricane Irene | As the storm’s outer bands reached New York on Saturday night, two kayakers capsized and had to be rescued off Staten Island }

U.S., incidents, science | August 27th, 2011 6:27 pm

I call it “Broks’s paradox”: the condition of believing that the mind is separate from the body, even though you know this belief to be untrue. (…)

Alexander Vilenkin, a physicist, believes that our universe is just one of an infinite number of similar regions. But “it follows from quantum mechanics” that the number of histories that can be played out in them is finite. The upshot of this crossplay of finitudes and infinities is that every possible history will play out in an infinite number of regions, which means there should be an infinite number of places with histories identical to our own down to the atomic level. “I find this rather depressing,” says Vilenkin, “but it is probably true.” The cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman, on the other hand, believes that “consciousness and its contents are all that exists,” the physical universe being “among the humbler contents of consciousness.” (…)

This brings us to death. The psychologist Jesse Bering believes we will never get our heads around the idea. He calls it “Unamuno’s paradox,” after the Spanish existentialist Miguel de Unamuno, who was troubled not so much by the prospect of his own death as by his inability in life to get any kind of imaginative purchase on what the state of being dead would be “like.”

{ Prospect | Continue reading }

photo { Lissy-Laricchia }

ideas, neurosciences | August 26th, 2011 8:55 pm

After returning from holiday, it’s likely you felt that the journey home by plane, car or train went much quicker than the outward journey, even though in fact both distances and journey are usually the same. So why the difference?

According to a new study it seems that many people find that, when taking a trip, the way back seems shorter. The findings suggest that this effect is caused by the different expectations we have, rather than being more familiar with the route on a return journey. (…)

“The ‘return trip effect’ also existed when respondents took a different, but equidistant, return route. You do not need to recognize a route to experience the effect.”

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Mitch Epstein, Kennedy Airport, New York City, 1973 }

psychology, transportation | August 26th, 2011 9:46 am

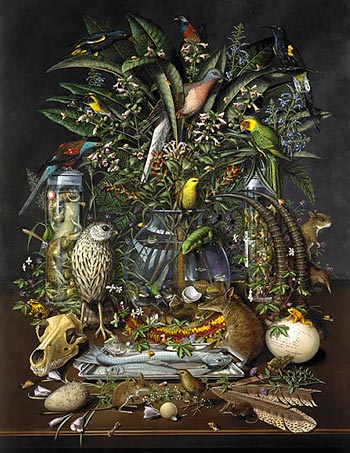

Take a piece of paper. Crumple it. Before you sink a three-pointer in the corner wastebasket, consider that you’ve just created an object of extraordinary mathematical and structural complexity, filled with mysteries that physicists are just starting to unfold.

“Crush a piece of typing paper into the size of a golf ball, and suddenly it becomes a very stiff object. The thing to realize is that it’s 90 percent air, and it’s not that you designed architectural motifs to make it stiff. It did it itself,” said physicist Narayan Menon of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “It became a rigid object. This is what we are trying to figure out: What is the architecture inside that creates this stiffness?”

{ Wired | Continue reading }

image { Richard Smith, Diary, 1975 }

mystery and paranormal, science | August 26th, 2011 9:44 am

We make decisions all our lives—so you’d think we’d get better and better at it. Yet research has shown that younger adults are better decision makers than older ones. Some Texas psychologists, puzzled by these findings, suspected the experiments were biased toward younger brains.

So, rather than testing the ability to make decisions one at a time without regard to past or future, as earlier research did, these psychologists designed a model requiring participants to evaluate each result in order to strategize the next choice, more like decision making in the real world.

The results: The older decision makers trounced their juniors.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Rory Watson }

psychology | August 25th, 2011 4:59 pm

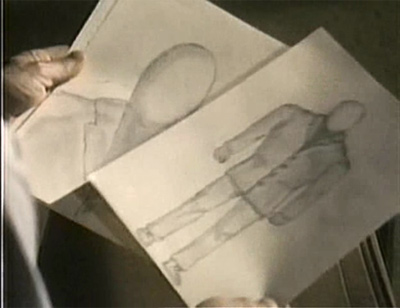

The Experiment: Split up twins after birth—and then control every aspect of their environments.

The payoff: Several disciplines would benefit enormously, but none more than psychology, in which the role of upbringing has long been particularly hazy. Developmental psychologists could arrive at some unprecedented insights into personality—finally explaining, for example, why twins raised together can turn out completely different, while those raised apart can wind up very alike.

{ Seven Creepy Experiments That Could Teach Us So Much (If They Weren’t So Wrong) | Wired | Continue reading }

science | August 24th, 2011 5:02 pm

A woman who took her partner’s name or a hyphenated name was judged as more caring, more dependent, less intelligent, more emotional, less competent, and less ambitious in comparison with a woman who kept her own name. A woman with her own name, on the other hand, was judged as less caring, more independent, more ambitious, more intelligent, and more competent, which was similar to an unmarried woman living together or a man.

Finally, a job applicant who took her partner’s name, in comparison with one with her own name, was less likely to be hired for a job and her monthly salary was estimated $1,250 lower (calculated to a working life, $500,000).

{ Basic and Applied Social Psychology | Continue reading | via The Jury Room }

Onomastics, economics, psychology, relationships | August 24th, 2011 5:01 pm

What would happen if the world stop spinning? (…)

Although the Earth isn’t likely to stop spinning any time soon, its has slowed considerably since its formation.

Because gravity is strongest at the poles, and the Earth bulges at the equator by about 21.4 kilometers (due to the Earth’s rotation), if the Earth were to stop spinning, water would move from the equatorial regions toward the poles. The low-lying areas of northern Europe, Asia and North America would be covered by ocean. Land currently covered by sea around the equator, however, would become dry land, forming a massive equatorial continent.

{ GeoJunk | Continue reading }

science, within the world | August 23rd, 2011 4:34 pm

The notion that our body odors are potent, chemically charged mating signals—so-called pheromones—is so pervasive in women’s magazines and websites, you would think that all you need is one good sweat to lure your guy.

If only it were so. Pheromones, in scientific parlance, are aromatic chemicals emitted by one member of a species that affect another member of the same species, either by altering its hormones or by compelling it to change its behavior. When they work, they are truly bewitching. For instance, when a female silkworm moth wants to get her guy, she sprays a chemical called bombykol from her abdominal gland and her targeted male transforms into a sex slave, trailing the scent until he mounts her. It’s an enviable feat. Still, it’s a big leap to extrapolate from bugs to people—or even to lab mice, for that matter. No scientific study has ever proven conclusively that mammals have pheromones.

{ Slate | Continue reading }

relationships, science | August 23rd, 2011 12:32 am

All of us, at times, ruminate or brood on a problem in order to make the best possible decision in a complex situation. But sometimes, rumination becomes unproductive or even detrimental to making good life choices. Such is the case in depression, where non-productive ruminations are a common and distressing symptom of the disorder. In fact, individuals suffering from depression often ruminate about being depressed. This ruminative thinking can be either passive and maladaptive (i.e., worrying) or active and solution-focused (i.e., coping). New research by Stanford University researchers provides insights into how these types of rumination are represented in the brains of depressed persons.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Erwin Blumenfeld }

brain, psychology | August 23rd, 2011 12:05 am

Sorbonne in Paris, France, on 8 August 1900 (…) David Hilbert’s address set the mathematical agenda for the 20th century. It crystallised into a list of 23 crucial unanswered questions, including how to pack spheres to make best use of the available space, and whether the Riemann hypothesis, which concerns how the prime numbers are distributed, is true.

Today many of these problems have been resolved, sphere-packing among them. Others, such as the Riemann hypothesis, have seen little or no progress. But the first item on Hilbert’s list stands out for the sheer oddness of the answer supplied by generations of mathematicians since: that mathematics is simply not equipped to provide an answer.

This curiously intractable riddle is known as the continuum hypothesis, and it concerns that most enigmatic quantity, infinity. Now, 140 years after the problem was formulated, a respected US mathematician believes he has cracked it. What’s more, he claims to have arrived at the solution not by using mathematics as we know it, but by building a new, radically stronger logical structure: a structure he dubs “ultimate L”.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

artwork { Jean-Michel Basquiat, Flexible, 1984 }

mathematics | August 19th, 2011 7:09 pm

Boys are maturing physically earlier than ever before. The age of sexual maturity has been decreasing by about 2.5 months each decade at least since the middle of the 18th century. Joshua Goldstein, director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, has used mortality data to prove this trend, which until now was difficult to decipher. What had already been established for girls now seems to also be true for boys: the time period during which young people are sexually mature but socially not yet considered adults is expanding.

{ MPG | Continue reading }

kids, science | August 19th, 2011 5:47 pm

At their most fundamental level, brains are made up of neurons. And those neurons collectively comprise the two main types of brain tissue: white matter is made up primarily of axons, and grey matter is made up of synapses, or the connections between neurons.

Grey matter exists as a thin, relatively flat sheet covering the rest of the brain, and is referred to as the cortex. When you compare the brains of different mammal species, you find that certain measurements of brain structure scale in similar ways. In other words, variables like grey matter volume, total number of synapses, white matter volume, number of neurons, surface area, axon diameter, and number of distinct cortical “areas” maintain common mathematical relationships with each other, whether you’re looking at the brains of mice, rabbits, dogs, cats, hyenas, kangaroos, bats, sloths, bonobos, or humans. (…)

Lots of networks have been compared to urban systems. (…) To what extent, though, might a brain be like a city? There’s the obvious analogy: neurons are like highways. Neurons are channels that carry information in the form of electric signals from one location within the brain to another, while highways are channels that transport people and materials from one location within a city to another. Cognitive scientists Mark Changizi and Marc Destefano think that the analogy goes deeper. (…) They argue that the organization of city highway networks is driven over time by political and economic forces, rather than explicitly planned based on principles of highway engineering – which means that city highway systems may be subject to a form of selection pressure similar to the selection pressure exerted on biological systems.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

photo { Keith Davis }

brain, ideas, transportation | August 19th, 2011 5:28 pm

It wasn’t so long ago we thought space and time were the absolute and unchanging scaffolding of the universe. Then along came Albert Einstein, who showed that different observers can disagree about the length of objects and the timing of events. His theory of relativity unified space and time into a single entity - space-time. It meant the way we thought about the fabric of reality would never be the same again.

But did Einstein’s revolution go far enough? Physicist Lee Smolin at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, doesn’t think so. He and a trio of colleagues are aiming to take relativity to a whole new level, and they have space-time in their sights. They say we need to forget about the home Einstein invented for us: we live instead in a place called phase space.

If this radical claim is true, it could solve a troubling paradox about black holes that has stumped physicists for decades. What’s more, it could set them on the path towards their heart’s desire: a “theory of everything” that will finally unite general relativity and quantum mechanics.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

science, space, theory | August 19th, 2011 5:15 pm

There’s a long line of research that associates marriage with reducing unhealthy habits such as smoking, and promoting better health habits such as regular checkups. However, new research is emerging that suggests married straight couples and cohabiting gay and lesbian couples in long-term intimate relationships may pick up each other’s unhealthy habits as well.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | August 19th, 2011 5:00 pm

4 billion years before present: the surface of a newly formed planet around a medium-sized star is beginning to cool down. It’s a violent place, bombarded by meteorites and riven by volcanic eruptions, with an atmosphere full of toxic gases. But almost as soon as water begins to form pools and oceans on its surface, something extraordinary happens. A molecule, or perhaps a set of molecules, capable of replicating itself arises.

This was the dawn of evolution. Once the first self-replicating entities appeared, natural selection kicked in, favouring any offspring with variations that made them better at replicating themselves. Soon the first simple cells appeared. The rest is prehistory.

Billions of years later, some of the descendants of those first cells evolved into organisms intelligent enough to wonder what their very earliest ancestor was like. What molecule started it all? (…)

When biologists first started to ponder how life arose, the question seemed baffling. In all organisms alive today, the hard work is done by proteins. Proteins can twist and fold into a wild diversity of shapes, so they can do just about anything, including acting as enzymes, substances that catalyse a huge range of chemical reactions. However, the information needed to make proteins is stored in DNA molecules. You can’t make new proteins without DNA, and you can’t make new DNA without proteins. So which came first, proteins or DNA?

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

artwork { Chris Ofili }

flashback, science | August 17th, 2011 11:12 am

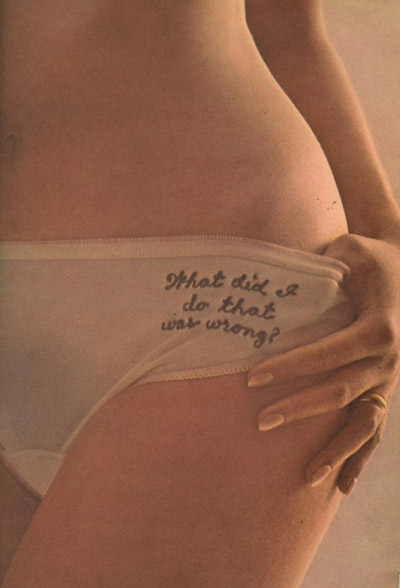

The projection of vagina, uterine cervix, and nipple to the sensory cortex in humans has not been reported.

The aim of this study was to map the sensory cortical fields of the clitoris, vagina, cervix, and nipple, toward an elucidation of the neural systems underlying sexual response.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we mapped sensory cortical responses to clitoral, vaginal, cervical, and nipple self-stimulation.

The genital sensory cortex, identified in the classical Penfield homunculus based on electrical stimulation of the brain only in men, was confirmed for the first time in the literature by the present study in women applying clitoral, vaginal, and cervical self-stimulation, and observing their regional brain responses using fMRI.

Activation of the genital sensory cortex by nipple self-stimulation was unexpected, but suggests a neurological basis for women’s reports of its erotogenic quality.

{ The Journal of Sexual Medicine | Continue reading }

photo { Richard Kern }

brain, sex-oriented | August 17th, 2011 9:12 am