science

The simplicity of modern life is making us more stupid, according to a scientific theory which claims humanity may have reached its intellectual and emotional peak as early as 4,000 BC.

Intelligence and the capacity for abstract thought evolved in our prehistoric ancestors living in Africa between 50,000 and 500,000 years ago, who relied on their wits to build shelters and hunt prey.

But in more civilised times where we no longer need to fight to survive, the selection process which favoured the smartest of our ancestors and weeded out the dullards is no longer in force.

Harmful mutations in our genes which reduce our “higher thinking” ability are therefore passed on through generations and allowed to accumulate, leading to a gradual dwindling of our intelligence as a species, a new study claims. […]

“I would wager that if an average citizen from Athens of 1000 BC were to appear suddenly among us, he or she would be among the brightest and most intellectually alive of our colleagues and companions, with a good memory, a broad range of ideas, and a clear-sighted view of important issues,” he said.

{ Guardian | Continue reading }

update 11/16 { Even if we do grant that cognitive evolutionary pressures have eased since 1000 BC, it’s not clear that this would make us ‘less intelligent.’ }

brain, science | November 14th, 2012 10:39 am

Today, the near 10-year-old Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture believes that neuroscience could make science’s greatest contribution to the field of architecture since physics informed fundamental structural methods, acoustic designs, and lighting calculations in the late 19th century. […]

With today’s sophisticated brain-imaging techniques, neuroscientists can examine how the brain processes environments, even with the complex limitations of, say, someone who’s blind, or autistic, or has dementia. […]

Macagno has been testing hospital design in a virtual-reality lab, and this work could bring us closer to that elusive hospital where, for example, no one gets lost. Other findings from the kind of research he is talking about may challenge what architects have practiced for years. For instance, hospital rooms for premature babies were long built to accommodate their medical equipment and caregivers, not to promote the development of the newborns’ brains. Neuroscience research tells us that the constant noise and harsh lighting of such environments can interfere with the early development of a baby’s visual and auditory systems.

{ Pacific Standard | Continue reading }

architecture, neurosciences | November 13th, 2012 11:34 am

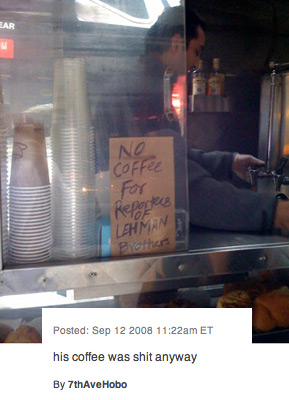

Coffee is under threat from climate change, according to a study which found that popular Arabica beans could face extinction within decades.

Rising global temperatures and subtle changes in seasonal conditions could make 99.7 per cent of Arabica-growing areas unsuitable for the plant by 2080. […]

Identifying new sites where arabica could be grown away from its natural home in the mountains of Ethiopia and South Sudan could be the only way of preventing the demise of the species, researchers said.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading }

unrelated {List of unsolved problems }

climate, food, drinks, restaurants | November 10th, 2012 8:29 am

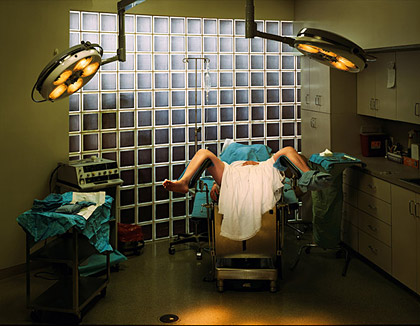

Many children spontaneously report memories of ‘past lives’. For believers, this is evidence for reincarnation; for others, it’s a psychological oddity. But what happens when they grow up?

Icelandic psychologists Haraldsson and Abu-Izzedin looked into it. They took 28 adults, members of the Druze community of Lebanon. They’d all been interviewed about past life memories by the famous reincarnationist Professor Ian Stephenson in the 70s, back when they were just 3-9 years old. Did they still ‘remember’? […]

As children they reported on average 30 distinct memories of past lives. As adults they could only remember 8, but of those, only half matched the ones they’d talked about previously.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

photo { Taryn Simon }

kids, memory | November 7th, 2012 11:31 am

Brains are very costly. Right now, just sitting here, my brain (even though I’m not doing much other than talking) is consuming about 20- 25 percent of my resting metabolic rate. That’s an enormous amount of energy, and to pay for that, I need to eat quite a lot of calories a day, maybe about 600 calories a day, which back in the Paleolithic was quite a difficult amount of energy to acquire. So having a brain of 1,400 cubic centimeters, about the size of my brain, is a fairly recent event and very costly.

The idea then is at what point did our brains become so important that we got the idea that brain size and intelligence really mattered more than our bodies? I contend that the answer was never, and certainly not until the Industrial Revolution.

Why did brains get so big? There are a number of obvious reasons. One of them, of course, is for culture and for cooperation and language and various other means by which we can interact with each other, and certainly those are enormous advantages. If you think about other early humans like Neanderthals, their brains are as large or even larger than the typical brain size of human beings today. Surely those brains are so costly that there would have had to be a strong benefit to outweigh the costs. So cognition and intelligence and language and all of those important tasks that we do must have been very important.

We mustn’t forget that those individuals were also hunter-gatherers. They worked extremely hard every day to get a living. A typical hunter-gatherer has to walk between nine and 15 kilometers a day. A typical female might walk 9 kilometers a day, a typical male hunter-gatherer might walk 15 kilometers a day, and that’s every single day. That’s day-in, day-out, there’s no weekend, there’s no retirement, and you do that for your whole life. It’s about the distance if you walk from Washington, DC to LA every year. That’s how much walking hunter-gatherers did every single year.

{ Daniel Lieberman/Edge | Continue reading }

brain, flashback, science | November 6th, 2012 2:07 pm

The Mariana Trench is the deepest part of the world’s oceans. It is located in the western Pacific Ocean, to the east of the Mariana Islands.

The trench reaches a maximum-known depth of 10.994 km or 6.831 mi at the Challenger Deep, a small slot-shaped valley in its floor, at its southern end, although some unrepeated measurements place the deepest portion at 11.03 kilometres (6.85 mi).

The trench is not the part of the seafloor closest to the center of the Earth. This is because the Earth is not a perfect sphere: its radius is about 25 kilometres (16 mi) less at the poles than at the equator. As a result, parts of the Arctic Ocean seabed are at least 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) closer to the Earth’s center than the Challenger Deep seafloor.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

related { What if you exploded a nuclear bomb at the bottom of the Marianas Trench? }

science, water | November 6th, 2012 1:11 pm

The eminent criminal psychologist and creator of the widely used Psychopathy Checklist paused before answering. “I think, in general, yes, society is becoming more psychopathic,” he said. “I mean, there’s stuff going on nowadays that we wouldn’t have seen 20, even 10 years ago. Kids are becoming anesthetized to normal sexual behavior by early exposure to pornography on the Internet. Rent-a-friend sites are getting more popular on the Web, because folks are either too busy or too techy to make real ones. … The recent hike in female criminality is particularly revealing. And don’t even get me started on Wall Street.”

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

psychology | November 6th, 2012 10:04 am

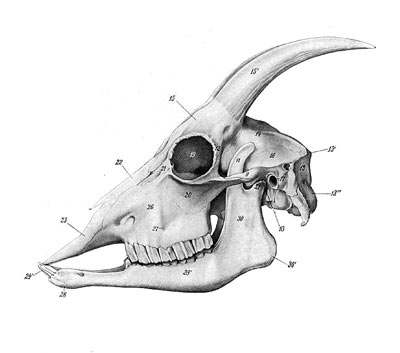

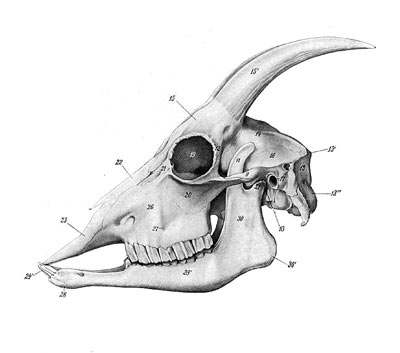

Cotard’s Syndrome is the delusional belief that one is dead or missing internal organs or other body parts. Those who suffer from this “delusion of negation” deny their own existence. The eponymous French neurologist Jules Cotard called it le délire de négation (”negation delirium”). […]

In a review of 100 cases, Berrios and Luque (1995) found that: “Depression was reported in 89% of subjects; the most common nihilistic delusions concerned the body (86%) and existence (69%).”

{ The Neurocritic | Continue reading }

image { Chris Scarborough }

psychology | November 6th, 2012 6:16 am

For more than 60 years, Robert Martensen’s lung cells replicated without a hitch, regulated by specialized enzymes called kinases. Much like thermostats that adjust the temperature in a room to make sure it’s not too hot or too cold, kinases make sure that the right number of new cells are created as old ones die. But sometime in his early sixties, something changed inside Martensen. One or more of the genes coding for his kinases mutated, causing his lung cells to begin replicating out of control.

At first the clusters of rogue cells were so small that Martensen had no idea they existed. Nor was anyone looking for them inside the lean, ruddy-faced physician, who exercised most days and was an energetic presence as the chief historian at the National Institutes of Health. Then came a day in February 2011 when Martensen noticed a telltale node in his neck while taking a shower. “I felt no pain,” he recalls, “but I knew what it was. I told myself in the shower that this was cancer—and that from that moment on, my life would be different.”

Martensen initially thought it was lymphoma, cancer of the lymph glands, which has a higher survival rate than many other cancers. But after a biopsy, he was stunned to discover he had late-stage lung cancer, a disease that kills 85 percent of patients within a year. Most survive just a few months. […]

He heard about a new drug being tested at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Developed by pharmaceutical giant Pfizer, the drug had dramatically reduced lung cancer tumors and prolonged life in the couple hundred patients who had so far used it, with few side effects. But there was a catch. The new med, called Xalkori, worked for only 3 to 5 percent of all lung cancer patients.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

photo { Patrick Romero }

genes, health, science | November 6th, 2012 6:02 am

Research shows that friends influence how girls and women view and judge their own body weight, shape and size. What Wasylkiw and Williamson’s work sheds light on, is how much of a young woman’s body concerns are shaped by her perceptions of peers’ concerns with their own body versus her peers’ actual body concerns. […]

They found that the more women felt under pressure to be thin, the more likely they were to have body image concerns, irrespective of their actual weight and shape. Interestingly, body talk between friends that focussed on exercise was related to lower body dissatisfaction.

{ Springer | Continue reading }

health, psychology | November 5th, 2012 3:02 pm

Rats use a sense that humans don’t: whisking. They move their facial whiskers back and forth about eight times a second to locate objects in their environment. Could humans acquire this sense? And if they can, what could understanding the process of adapting to new sensory input tell us about how humans normally sense? At the Weizmann Institute, researchers explored these questions by attaching plastic “whiskers” to the fingers of blindfolded volunteers and asking them to carry out a location task. The findings, which recently appeared in the Journal of Neuroscience, have yielded new insight into the process of sensing, and they may point to new avenues in developing aids for the blind.

{ Weizmann Institute of Science | Continue reading }

science | November 5th, 2012 3:00 pm

In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties of a particle, such as position x and momentum p, can be known simultaneously. The more precisely the position of some particle is determined, the less precisely its momentum can be known, and vice versa. The original heuristic argument that such a limit should exist was given by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, after whom it is sometimes named, as the Heisenberg principle. […]

Historically, the uncertainty principle has been confused with a somewhat similar effect in physics, called the observer effect, which notes that measurements of certain systems cannot be made without affecting the systems.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

photo { Jason Lazarus }

ideas, photogs, science | November 5th, 2012 2:50 pm

Since Apollo 17’s flight in 1972, no humans have been back to the moon, or gone anywhere beyond low Earth orbit. No one has traveled faster than the crew of Apollo 10. (Since the last flight of the supersonic Concorde in 2003, civilian travel has become slower.) Blithe optimism about technology’s powers has evaporated, too, as big problems that people had imagined technology would solve, such as hunger, poverty, malaria, climate change, cancer, and the diseases of old age, have come to seem intractably hard.

{ Technology Review | Continue reading }

economics, science, technology | October 31st, 2012 1:20 pm

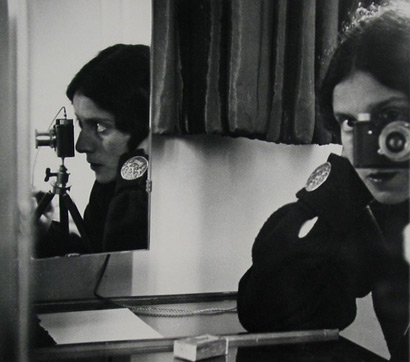

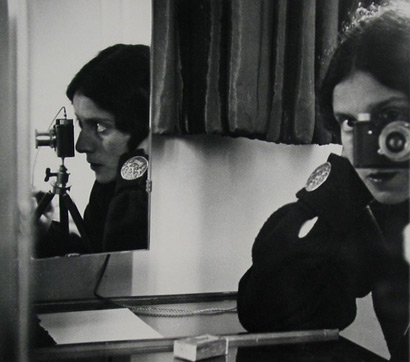

Humans specifically seek out the eyes of others, rather than just the middle of their faces, according to a new study proposed by an 11-year-old boy that uses characters from video game Dungeons and Dragons.

Cognitive scientist Alan Kingstone, director of the brain and research lab at the University of British Columbia in Canada, first became interested in testing whether people look at each others eyes, or simply the centre of their heads, two years ago. However, some had suggested an answer to the question would be impossible to find because our eyes happen to always be roughly in the centre of our heads.

Taking the problem home to his family, Alan’s then 11-year-old son, Julian Levy – named lead author of the subsequent paper, titled “Monsters are people too”, published in British Royal Society journal Biology Letters – had “a clever idea that only a kid’s brain could have,” Kingstone said.

{ Cosmos | Continue reading }

photo { Ilse Bing, Self-Portrait in Mirrors, 1932 }

eyes, faces, kids | October 31st, 2012 11:52 am

Contemplating death doesn’t necessarily lead to morose despondency, fear, aggression or other negative behaviors, as previous research has suggested. […]

The awareness of mortality can motivate people to enhance their physical health and prioritize growth-oriented goals; live up to positive standards and beliefs; build supportive relationships and encourage the development of peaceful, charitable communities; and foster open-minded and growth-oriented behaviors.

{ Improbable Research | Continue reading }

photo { Sasha Kurmaz }

psychology | October 31st, 2012 11:49 am

The U.S. government is surreptitiously collecting the DNA of world leaders, and is reportedly protecting that of Barack Obama. Decoded, these genetic blueprints could provide compromising information. In the not-too-distant future, they may provide something more as well—the basis for the creation of personalized bioweapons that could take down a president and leave no trace.

{ Atlantic | Continue reading }

genes, spy & security, technology | October 31st, 2012 8:05 am

New research shows a simple reason why even the most intelligent, complex brains can be taken by a swindler’s story – one that upon a second look offers clues it was false.

When the brain fires up the network of neurons that allows us to empathize, it suppresses the network used for analysis, a pivotal study led by a Case Western Reserve University researcher shows. […]

When the analytic network is engaged, our ability to appreciate the human cost of our action is repressed.

At rest, our brains cycle between the social and analytical networks. But when presented with a task, healthy adults engage the appropriate neural pathway, the researchers found.

The study shows for the first time that we have a built-in neural constraint on our ability to be both empathetic and analytic at the same time.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Jonathan Waiter }

neurosciences, relationships | October 30th, 2012 4:08 pm

This study offers the first combined quantitative assessment of suicide terrorists and rampage, workplace, and school shooters who attempt suicide, to investigate where there are statistically significant differences and where they appear almost identical. Suicide terrorists have usually been assumed to be fundamentally different from rampage, workplace, and school shooters.

Many scholars have claimed that suicide terrorists are motivated purely by ideology, not personal problems, and that they are not even suicidal. This study’s focus was on attacks and attackers in the United States from 1990 to 2010 and concluded that the differences between these offenders were largely superficial. Prior to their attacks, they struggled with many of the same personal problems, including social marginalization, family problems, work or school problems, and precipitating crisis events.

{ Homicide Studies/SAGE | Continue reading }

guns, horror, psychology | October 30th, 2012 3:45 pm

Which personality traits are associated with physical attractiveness? Recent findings suggest that people high in some dark personality traits, such as narcissism and psychopathy, can be physically attractive. But what makes them attractive?

Studies have confounded the more enduring qualities that impact attractiveness (i.e., unadorned attractiveness) and the effects of easily manipulated qualities such as clothing (i.e., effective adornment). In this multimethod study, we disentangle these components of attractiveness, collect self-reports and peer reports of eight major personality traits, and reveal the personality profile of people who adorn themselves effectively. Consistent with findings that dark personalities actively create positive first impressions, we found that the composite of the Dark Triad—Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy—correlates with effective adornment. This effect was also evident for psychopathy measured alone.

This study provides the first experimental evidence that dark personalities construct appearances that act as social lures—possibly facilitating their cunning social strategies.

{ Social Psychological and Personality Science /SAGE }

charcoal and pastel on paper { Johannes Kahrs, Untitled (figure with star), 2007 }

psychology | October 30th, 2012 3:31 pm

Our brains are so adept at detecting faces that we often see them in random patterns, such as clouds or the gnarled bark of a tree. Occasionally one of these illusory faces comes along that resembles a celebrity and the story ends up in the news - like when Michael Jackson’s face appeared on the surface of a piece of toast. A new study asks whether some people are more prone than others to perceiving these illusory faces. […]

The key finding is that people who scored high in paranormal belief or religiosity were more likely to see face-like areas in the pictures compared with the sceptics and atheists.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

photo { Tono Stano }

psychology | October 30th, 2012 2:36 pm