science

With a little practice, one could learn to tell a lie that may be indistinguishable from the truth.

New Northwestern University research shows that lying is more malleable than previously thought, and with a certain amount of training and instruction, the art of deception can be perfected.

People generally take longer and make more mistakes when telling lies than telling the truth, because they are holding two conflicting answers in mind and suppressing the honest response, previous research has shown. Consequently, researchers in the present study investigated whether lying can be trained to be more automatic and less task demanding.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | December 7th, 2012 2:59 pm

People who recall being absolved of their sins, are more likely to donate money to the church, according to research published today in the journal Religion, Brain and Behavior.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Michael Wolf }

economics, psychology | December 6th, 2012 10:05 am

science | December 6th, 2012 9:48 am

For thousands of years, a core pursuit of medical science has been the careful observation of physical symptoms and signs. Through these observations, supplemented more recently by investigative techniques, an understanding of how symptoms and signs are generated by disease has developed. However, there is a group of patients with symptoms and signs that, from the earliest medical records to the present day, elude a diagnosis with a typical ‘organic’ disease. This is not simply because of an absence of pathology after sufficient investigation, rather that symptoms themselves are inconsistent with those occurring in typical disease. In times past, these symptoms were said to be ‘hysterical’, a term now replaced by the less pejorative but no more enlightening labels: ‘medically unexplained’, ‘psychogenic’, ‘conversion’, ‘non-organic’ and ‘functional’.

There are numerous historical examples of patients identified as having hysteria who would now be diagnosed with an organic medical disorder. Some have assumed that this process of salvaging patients from (mis)diagnosis with hysteria would continue inexorably until a ‘proper’ medical diagnosis was achieved. Slater (1965), in his influential paper on the topic, described the diagnosis of hysteria as ‘a disguise for ignorance and a fertile source of clinical error’. In other words, with increasing medical knowledge, all patients would be rescued from a diagnostic category that did little more than assert that they were ‘too difficult’.

This has not come to pass (Stone et al., 2005). Recent epidemiological work has demonstrated that neurologists continue to diagnose a ‘non-organic’ disorder in ∼16% of their patients, making this the second most common diagnosis of neurological outpatients.

{ Brain/Oxford Journals | Continue reading }

photo { Paul Himmel }

health, neurosciences, psychology | December 5th, 2012 3:17 pm

Uptalk is the use of a rising, questioning intonation when making a statement, which has become quite prevalent in contemporary American speech. Women tend to use uptalk more frequently than men do, though the reasons behind this difference are contested. I use the popular game show Jeopardy! to study variation in the use of uptalk among the contestants’ responses, and argue that uptalk is a key way in which gender is constructed through interaction. While overall, Jeopardy! contestants use uptalk 37 percent of the time, there is much variation in the use of uptalk. The typical purveyor of uptalk is white, young, and female. Men use uptalk more when surrounded by women contestants, and when correcting a woman contestant after she makes an incorrect response. Success on the show produces different results for men and women. The more successful a man is, the less likely he is to use uptalk; the more successful a woman is, the more likely she is to use uptalk.

{ SAGE }

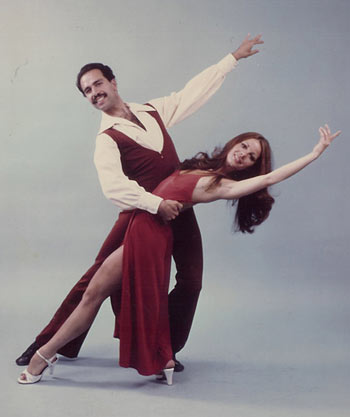

photo { Billy Kidd }

genders, psychology | December 5th, 2012 3:02 pm

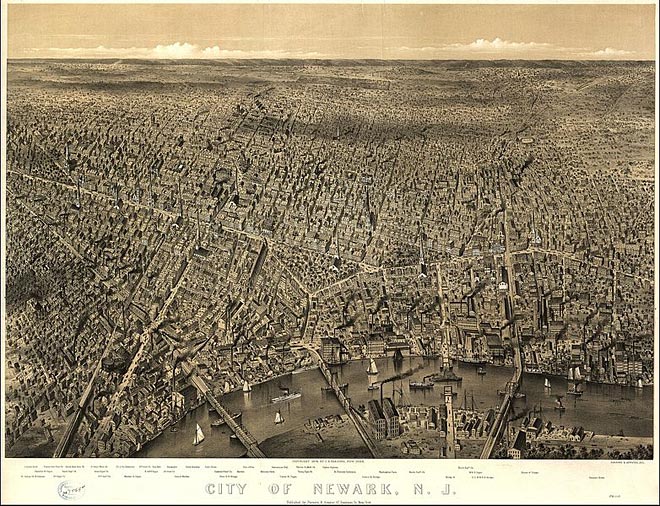

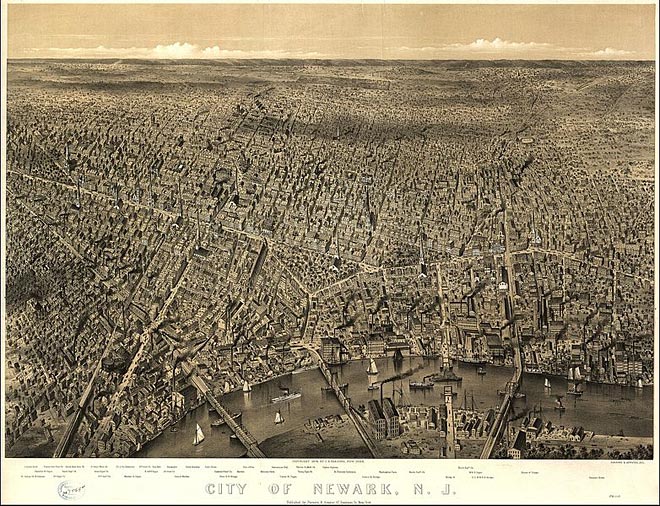

With a homicide rate historically more than three times greater than the rest of the United States, Newark, N.J., isn’t a great vacation spot. But it’s a great place for a murder study.

Led by April Zeoli, an assistant professor of criminal justice, a group of researchers at Michigan State University tracked homicides around Newark from 1982 to 2008, using analytic software typically used by medical researchers to track the spread of diseases. They found that “homicide clusters” in Newark, as researchers called them, spread and move throughout a city much the same way diseases do. Murders, in other words, did not surface randomly—they began in the city center and moved in “diffusion-like processes” across the city.

The study also found that the there were areas of Newark that, despite being beset by violence on all sides, remained almost completely immune to the surrounding trends over the entire course of the 26 years studied.

{ Vice | Continue reading }

U.S., guns, science | December 5th, 2012 12:22 pm

This was terrible news for neuroscience—if six studies led to six different answers, why should anybody believe anything that neuroscientists had to say? […] And then, surprisingly, the field prospered. Brain imaging became more, not less, popular. The technique of PET was replaced with the more flexible technique of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which allowed scientists to study people’s brains without the use of the risky radioactive tracers, and to conduct longer studies that collected more data and yielded more reliable results. […]

After two decades of almost complete dominance, a few bright souls started speaking up, asking: Are all these brain studies really telling us much as we think they are?

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

related { Neuroscience Team Explains Why Old People Get Scammed }

neurosciences | December 4th, 2012 6:00 am

In 1870, German chemist Erich von Wolf analyzed the iron content of green vegetables and accidentally misplaced a decimal point when transcribing data from his notebook. As a result, spinach was reported to contain a tremendous amount of iron—35 milligrams per serving, not 3.5 milligrams (the true measured value). While the error was eventually corrected in 1937, the legend of spinach’s nutritional power had already taken hold, one reason that studio executives chose it as the source of Popeye’s vaunted strength.

The point, according to Samuel Arbesman, an applied mathematician and the author of the delightfully nerdy “The Half-Life of Facts,” is that knowledge—the collection of “accepted facts”—is far less fixed than we assume. In every discipline, facts change in predictable, quantifiable ways, Mr. Arbesman contends, and understanding these changes isn’t just interesting but also useful. For Mr. Arbesman, Wolf’s copying mistake says less about spinach than about the way scientific knowledge propagates.

Copying errors, it turns out, aren’t uncommon and fall into characteristic patterns, such as deletions and duplications—exactly the sorts of mistakes that geneticists have identified in DNA. Using approaches adapted from genetics, paleographers—scientists who study ancient writing—use these accumulated errors to trace the age and origins of a document, much in the same way biologists use the accumulation of genetic mutations to assess how similar two species are to each other. For example, by analyzing the oddities and duplicated errors in the 58 surviving versions of “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue” from Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales,” researchers deduced the content of the original version.

Mr. Arbesman’s interest in the spread of knowledge also leads him to the story of Brontosaurus, the lovable, distinct herbivore we all grew up with—only it never existed. Originally described in 1879 by Othniel Marsh, the Brontosaurus was soon determined to be a type of dinosaur that Marsh had already discovered in 1877, the Apatosaurus. But since the original Apatosaurus was just “a tiny collection of bones,” while the Brontosaurus that Marsh named “went on to be supplemented with a complete skeleton, beautiful to behold,” the second discovery captured the public’s imagination and the name “Brontosaurus” stuck for nearly a century. Only recently has the name “Apatosaurus” started to gain traction.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

incidents, science | December 4th, 2012 5:45 am

Over the second half of the 20th century, the average age for girls to begin breast development has dropped by a year or more in the industrialized world. And the age of first menstruation, generally around 12, has advanced by a matter of months. Hispanic and black girls may be experiencing an age shift much more pronounced. […]

“If you basically say that the onset of puberty has a bell-shaped distribution, it seems to many of us the whole curve is shifting to the left,” says Paul Kaplowitz, chief of the division of endocrinology and diabetes at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. More girls, he says, are starting puberty before age 8, putting them at “the lower end of the new normal range.”

Researchers are now turning their attention to what could be driving the trend. Many scientists suspect that younger puberty is a consequence of an epidemic of childhood obesity, citing studies that find development closely tied to the accumulation of body fat. But there are other possibilities, including the presence of environmental chemicals that can mimic the biological properties of estrogen, and psychological and social stressors that might alter the hormonal makeup of a young body.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

hormones, kids, science | November 27th, 2012 4:07 pm

When I was a kid, probably about 9 or 10 [years old], we went to an Indian restaurant for dinner. Just as my dad was about to pay, he suddenly tinked his spoon against his glass and stood up. The whole restaurant went silent. My dad said, “I’d just like to thank you all for coming; some from just round the corner, some from much further afield. You’re all most welcome to join us for a little drinks reception across the road.’

And so an entire restaurant of strangers who had never seen us before were all applauding wildly because they didn’t want to be seen as gatecrashers. We just took off. He [told me] we’re not going to the pub really and [explained that his] old friend Malcolm had [just opened a new pub across the street].

[…]

If you’re an intelligent psychopath and violent [and get a good start], there are any number of exciting occupations, anything from special forces operative to head of a criminal syndicate.

{ Kevin Dutton/Time | Continue reading }

psychology | November 27th, 2012 3:01 pm

Young children are inclined to see purpose in the natural world. Ask them why we have rivers, and they’ll likely tell you that we have rivers so that boats can travel on them (an example of a “teleological explanation”). […] A new study with 80 physical scientists finds that they too have a latent tendency to endorse similar teleological explanations for why nature is the way it is. They label those explanations as false most of the time, but put them under time pressure, and their child-like, quasi-religious beliefs shine through.

Deborah Kelemen and her colleagues presented 80 scientists (including physicists, chemists and geographers) with 100 one-sentence statements and their task was to say if each one was true or false. Among the items were teleological statements about nature, such as “Trees produce oxygen so that animals can breathe”. Crucially, half the scientists had to answer under time pressure - just over 3 seconds for each statement - while the others had as long as they liked. There were also control groups of college students and the general public. […]

When they were rushed, the scientists endorsed 29 per cent of teleological statements compared with 15 per cent endorsed by the un-rushed scientists. This is consistent with the idea that a tendency to endorse teleological beliefs lingers in the scientists’ minds. This unscientific thinking is usually suppressed, but time pressure undermines that conscious suppression. […]

Scientists who admitted having religious beliefs, or beliefs about Mother Nature being one big organism, were more prone than most to endorsing teleological explanation under time pressure.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

psychology | November 27th, 2012 3:00 pm

Critics claim that evolutionary biology is, at best, guesswork. The reality is otherwise. Evolutionists have nailed down how an enormous number of previously unexplained phenomena—in anatomy, physiology, embryology, behavior—have evolved. There are still mysteries, however, and one of the most prominent is the origins of homosexuality. […]

If homosexuality is in any sense a product of evolution—and it clearly is, for reasons to be explained—then genetic factors associated with same-sex preference must enjoy some sort of reproductive advantage. The problem should be obvious: If homosexuals reproduce less than heterosexuals—and they do—then why has natural selection not operated against it?

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

photo { Holly Andres }

relationships, science | November 21st, 2012 11:23 am

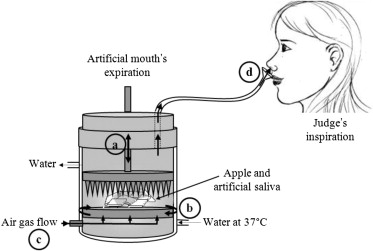

In a year or two, augmented reality (AR) headsets such as Google Glass may double up as a virtual dieting pill. New research from the University of Tokyo shows that a very simple AR trick can reduce the amount that you eat by 10% — and yes, the same trick, used in the inverse, can be used to increase food consumption by 15%, too.

The AR trick is very simple: By donning the glasses, the University of Tokyo’s special software “seamlessly” scales up the size of your food. […]

It has been shown time and time again that large plates and large servings encourage you to consume more. In one study, restaurant-goers ate more food when equipped with smaller forks; but at home, the opposite is true. In another study, it was shown that you eat more food if the color of your plate matches what you’re eating.

{ ExtremeTech | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, psychology, technology | November 21st, 2012 11:06 am

Customers buy a saliva kit online at 23andMe.com, send it in, and the company extracts their DNA from cheek cells preserved in saliva. In its labs, 23andMe then copies the DNA many times until there’s enough to be genotyped. Then, says lesbian scientist Emily Drabant, the DNA is examined for tens of thousands of genetic variants linked to various conditions and traits, and within weeks users get more than 100 reports on diseases, more than 50 reports on traits, more than 40 reports on carrier status, and more than 20 for drug response. […]

The most commonly requested test, Drabant says, is for sexual orientation, a particularly controversial area. […] The company initiated its sexual orientation project about six months ago, and researchers are hoping that tens of thousands of LGBT folks take the genetic test and fill out the accompanying survey — the information from which allows 23andMe to see patterns among, for example, gay men or transgender women. […] As soon as the company has a big enough sample, it plans to make those results public.

{ Advocate | Continue reading }

genes, relationships | November 20th, 2012 8:27 am

It’s not surprising that social norms influence consumer behavior. When everybody else wants to spend $400 on the new iPad, it makes sense that you’ll be more willing to spend $400 on a new iPad. The question is, how far does this social influence extend?

A new study led by Ivo Vlaev examines how social norms influence spending on a good that ought to be on the opposite end of the social influence spectrum from consumer electronics: pain reduction. If somebody stabs you in the foot with a steak knife, you would assume your desire to alleviate that pain has nothing to do with the decision of somebody else who suffered the same stabbing. But that’s not what Vlaev and his team found. When it came to avoiding a painful electric shock, people didn’t just make decisions based their own pain, they also took into account how much other people wanted to reduce that same pain. […]

The fact that our desire to alleviate pain is subject to social influences has important implications for health care systems. For example, if it seems like back pain is something you’re expected to live with, people might be less willing to seek treatment for it.

{ peer-reviewed by my neurons | Continue reading }

health, psychology | November 20th, 2012 8:02 am

Psychologists Segal-Caspi and colleagues took 118 female Israeli students and videotaped them walking into a room and reading a weather forecast. Then other students - male and female - judged the ‘targets’ on attractiveness, but also tried to work out their personality, purely based on 60 seconds of video.

So what happened?

The judges judged prettier women as having stereotypically ‘better’ personality traits e.g. less neurotic and more friendly. Interestingly, both male and female judges did this, and there were no significant differences between the genders.

So there’s a tendency to think that those we find attractive are also beautiful on the inside.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

psychology | November 20th, 2012 8:00 am

This report spells out what the world would be like if it warmed by 4 degrees Celsius, which is what scientists are nearly unanimously predicting by the end of the century, without serious policy changes.

The 4°C scenarios are devastating: the inundation of coastal cities; increasing risks for food production potentially leading to higher malnutrition rates; many dry regions becoming dryer, wet regions wetter; unprecedented heat waves in many regions, especially in the tropics; substantially exacerbated water scarcity in many regions; increased frequency of high-intensity tropical cyclones; and irreversible loss of biodiversity, including coral reef systems. […]

The science is unequivocal that humans are the cause of global warming, and major changes are already being observed: global mean warming is 0.8°C above pre industrial levels; oceans have warmed by 0.09°C since the 1950s and are acidifying; sea levels rose by about 20 cm since pre-industrial times and are now rising at 3.2 cm per decade; an exceptional number of extreme heat waves occurred in the last decade; major food crop growing areas are increasingly affected by drought.

{ World Bank | PDF }

climate, future, uh oh | November 19th, 2012 3:12 pm

{ Why is the polyp Hydra immortal? Researchers from Kiel University decided to study it — and unexpectedly discovered a link to aging in humans. | Kurzweil | full story }

mystery and paranormal, science | November 19th, 2012 11:09 am

It’s all about the fact that people want to achieve two things at the same time. We want to think of ourselves as honest, wonderful people, and then we want to benefit from cheating. Our ability to rationalize our own actions can actually help us be more dishonest while thinking of ourselves as honest. So the idea that everybody else does it, or the idea that nobody is really going to suffer, or the idea that the entity you are stealing from is actually a bad entity, or the idea that you don’t see it—all of those things help people be dishonest.

{ Daniel Ariely/The Politic | Continue reading }

economics, psychology, scams and heists | November 18th, 2012 4:11 pm

Inattentional blindness-the failure to see visible and otherwise salient events when one is paying attention to something else-has been proposed as an explanation for various real-world events. In one such event, a Boston police officer chasing a suspect ran past a brutal assault and was prosecuted for perjury when he claimed not to have seen it. However, there have been no experimental studies of inattentional blindness in real-world conditions. We simulated the Boston incident by having subjects run after a confederate along a route near which three other confederates staged a fight. At night only 35% of subjects noticed the fight; during the day 56% noticed. We manipulated the attentional load on the subjects and found that increasing the load significantly decreased noticing. These results provide evidence that inattentional blindness can occur during real-world situations, including the Boston case.

{ i-Perception | PDF }

eyes, neurosciences | November 14th, 2012 3:27 pm