neurosciences

Although there has been some empirical research on earworms, songs that become caught and replayed in one’s memory over and over again, there has been surprisingly little empirical research on the more general concept of the musical hook, the most salient moment in a piece of music, or the even more general concept of what may make music ‘catchy’. […]

Every piece of music will have a hook – the catchiest part of the piece, whatever that may be – but some pieces of music clearly have much catchier hooks than others. […]

One study has shown that after only 400 ms, listeners can identify familiar music with a significantly greater frequency than one would expect from chance. […]

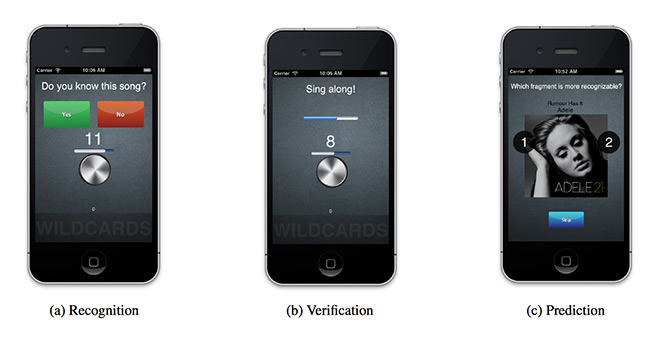

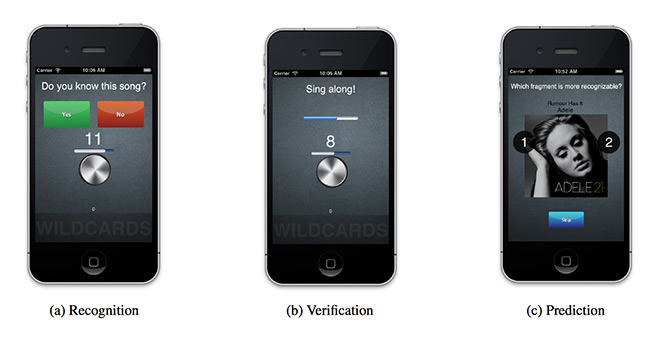

We have designed an experiment that we believe will help to quantify the effect of catchiness on musical memory. […] Hooked, as we have named the game, comprises three essential tasks: a recognition task, a verification task, and a prediction task. Each of them responds to a scientific need in what we felt was the most entertaining fashion possible. In this way, we hope to be able recruit the largest number of subjects possible without sacrificing scientific quality.

{ Music Cognition Group | PDF | Download the Game }

music, neurosciences | December 17th, 2013 1:22 pm

Specifically, they reported that men’s brains had more connectivity within each brain hemisphere, whereas women’s brains had more connectivity across the two hemispheres. Moreover, they stated or implied, in their paper and in statements to the press, that these findings help explain behavioral differences between the sexes, such as that women are intuitive thinkers and good at multi-tasking whereas men are good at sports and map-reading. […]

So, the wiring differences between the sexes aren’t that large. And we don’t really know their functional significance, if any. […]

[L]et’s set this new brain wiring study in the context of previous research. Verma and her team admit that a previous paper looking at the brain wiring of 439 participants failed to find significant differences between the sexes. What about studies on the corpus callosum – the thick bundle of fibres that connects the two brain hemispheres? If women really have more cross-talk across the brain, this is one place where you’d definitely expect them to have more connectivity. And yet a 2012 diffusion tensor paper found “a stronger inter-hemispheric connectivity between the frontal lobes in males than females”. Hmm. Another paper from 2006 found little difference in thickness of the callosum according to sex. Finally a meta-analysis from 2009: “The alleged sex-related corpus callosum size difference is a myth,” it says.

{ Wired | Continue reading }

A small sample of the more credulous media uptake:

“Male and female brains wired differently, scans reveal”, The Guardian 12/2/2013

“Striking differences in brain wiring between men and women”, EarthSky 12/3/2013

“Is Equal Opportunity Threatened By New Findings That Female And Male Brains Are Different?”, Forbes 12/3/2013

”The hardwired difference between male and female brains could explain why men are ‘better at map reading’ and why women are ‘better at remembering a conversation’”, The Independent 12/3/2013

”Sex and Brains: Vive la différence!”, The Economist 12/7/2013

“Differences in How Men and Women Think Are Hard-Wired”, WSJ 12/9/2013

“Brains of women, men are actually wired differently”, New Scientist 12/12/2013

“Gender differences are hard-wired”, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review 12/15/2013

Some more thoughtful reactions:

“Study: The Brains of Men and Women Are Different… WIth A Few Major Caveats”, Forbes 12/8/2013

“Do Men And Women Have Different Brains?”, NPR 12/13/2013

“Time to ditch the ‘Venus and Mars’ cliche”, The New Zealand Herald 12/14/2013

{ Language Log | Continue reading }

art { Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Sylvette David in Green Chair, 1954 }

brain, genders, neurosciences | December 16th, 2013 8:06 am

The eminent sociologist Erving Goffman suggested that life is a series of performances, in which we are all continually managing the impression we give other people. […]

But recently we have learned that some of our social responses occur even without conscious consideration. […] [L]ab experiments show that when people happen to be holding a hot drink rather than a cold one, they are more likely to trust strangers. Another found that people are much more helpful and generous when they step off a rising escalator than when they step off a descending escalator—in fact, ascending in any fashion seems to trigger nicer behavior. […]

Neuroscientists have found that environmental cues trigger immediate responses in the human brain even before we are aware of them. As you move into a space, the hippocampus, the brain’s memory librarian, is put to work immediately. It compares what you are seeing at any moment to your earlier memories in order to create a mental map of the area, but it also sends messages to the brain’s fear and reward centers. Its neighbor, the hypothalamus, pumps out a hormonal response to those signals even before most of us have decided if a place is safe or dangerous. Places that seem too sterile or too confusing can trigger the release of adrenaline and cortisol, the hormones associated with fear and anxiety. Places that seem familiar, navigable, and that trigger good memories, are more likely to activate hits of feel-good serotonin, as well as the hormone that rewards and promotes feelings of interpersonal trust: oxytocin.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

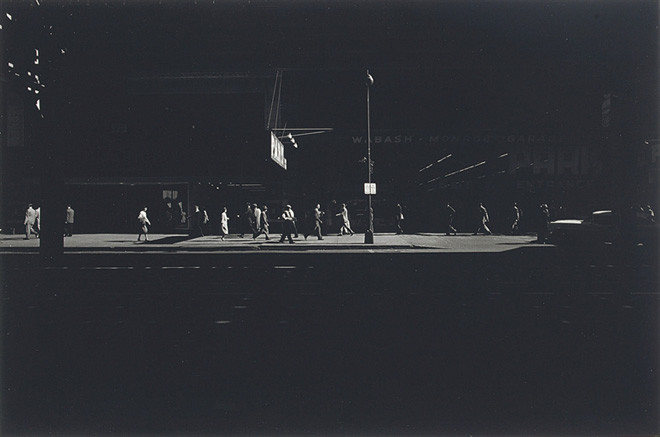

photo { Dennis Stock }

neurosciences, psychology, relationships | December 13th, 2013 11:28 am

Teenagers’ brains are wired to confront a threat instead of retreating, research suggests. The results may help explain why criminal activity peaks during adolescence.

{ Science News | Continue reading }

fights, kids, neurosciences | November 15th, 2013 12:15 pm

Our brains perceive objects in everyday life of which we may never be aware, a study finds, challenging currently accepted models about how the brain processes visual information. […]

“There’s a brain signature for meaningful processing,” Sanguinetti said. A peak in the averaged brainwaves called N400 indicates that the brain has recognized an object and associated it with a particular meaning.

“It happens about 400 milliseconds after the image is shown, less than a half a second,” said Peterson. “As one looks at brainwaves, they’re undulating above a baseline axis and below that axis. The negative ones below the axis are called N and positive ones above the axis are called P, so N400 means it’s a negative waveform that happens approximately 400 milliseconds after the image is shown.”

The presence of the N400 peak indicates that subjects’ brains recognize the meaning of the shapes on the outside of the figure.

“The participants in our experiments don’t see those shapes on the outside; nonetheless, the brain signature tells us that they have processed the meaning of those shapes,” said Peterson. “But the brain rejects them as interpretations, and if it rejects the shapes from conscious perception, then you won’t have any awareness of them.”

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | November 13th, 2013 4:22 pm

Can the experience of an emotion persist once the memory for what induced the emotion has been forgotten? We capitalized on a rare opportunity to study this question directly using a select group of patients with severe amnesia. […]

Our findings provide direct evidence that a feeling of emotion can endure beyond the conscious recollection for the events that initially triggered the emotion.

{ PNAS | Continue reading }

memory | October 22nd, 2013 3:53 pm

Neurons communicate using electrical signals. They transmit these signals to neighboring cells via special contact points known as synapses. When new information needs processing, the nerve cells can develop new synaptic contacts with their neighboring cells or strengthen existing synapses. To be able to forget, these processes can also be reversed. The brain is consequently in a constant state of reorganization, yet individual neurons need to be prevented from becoming either too active or too inactive. The aim is to keep the level of activity constant, as the long-term overexcitement of neurons can result in damage to the brain.

Too little activity is not good either. “The cells can only re-establish connections with their neighbors when they are ‘awake’, so to speak, that is when they display a minimum level of activity”, explains Mark Hübener, head of the study. The international team of researchers succeeded in demonstrating for the first time that the brain is able to compensate even massive changes in neuronal activity within a period of two days, and can return to an activity level similar to that before the change. […]

In their study, they examined the visual cortex of mice that recently went blind. As expected, but never previously demonstrated, the activity of the neurons in this area of the brain did not fall to zero but to half of the original value. […] After just a few hours, they could clearly observe how the contact points between the affected neurons and their neighboring cells increased in size. When synapses get bigger, they also become stronger and signals are transmitted faster and more effectively. As a result of this synaptic upscaling, the activity of the affected network returned to its starting value after a period of between 24 and 48 hours.

{ Wired Cosmos | Continue reading }

photo { John Swannell }

brain, neurosciences | October 18th, 2013 1:22 pm

Amnesia comes in distinct varieties. In “retrograde amnesia,” a movie staple, victims are unable to retrieve some or all of their past knowledge—Who am I? Why does this woman say that she’s my wife?—but they can accumulate memories for everything that they experience after the onset of the condition. In the less cinematically attractive “anterograde amnesia,” memory of the past is more or less intact, but those who suffer from it can’t lay down new memories; every person encountered every day is met for the first time. In extremely unfortunate cases, retrograde and anterograde amnesia can occur in the same individual, who is then said to suffer from “transient global amnesia,” a condition that is, thankfully, temporary. Amnesias vary in their duration, scope, and originating events: brain injury, stroke, tumors, epilepsy, electroconvulsive therapy, and psychological trauma are common causes, while drug and alcohol use, malnutrition, and chemotherapy may play a part. […]

When you asked Molaison a question, he could retain it long enough to answer; when he was eating French toast, he could remember previous mouthfuls and could see the evidence that he had started eating it. His unimpaired ability to do these sort of things illustrated a distinction, made by William James, between “primary” and “secondary” memory. Primary memory, now generally known as working memory, evidently did not depend upon the structures that Scoville had removed. The domain of working memory is a hybrid of the instantaneous present and of what James referred to as the “just past.” The experienced present has duration; it is not a point but a plateau. For those few seconds of the precisely now and the just past, the present is unarchived, accessible without conscious search. Beyond that, we have to call up the fragments of past presents. The plateau of Molaison’s working memory was between thirty and sixty seconds long—not very different from that of most people—and this was what allowed him to eat a meal, read the newspaper, solve endless crossword puzzles, and carry on a conversation. But nothing that happened on the plateau of working memory stuck, and his past presents laid down no sediments that could be dredged up by any future presents.

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

incidents, memory | October 18th, 2013 1:17 pm

The prevalence of depression among those with migraine is approximately twice as high as for those without the disease (men: 8.4% vs. 3.4%; women 12.4% vs. 5.7%), according to a new study published by University of Toronto researchers. […]

Consistent with prior research, the prevalence of migraines was much higher in women than men, with one in every seven women, compared to one in every 16 men, reporting that they had migraines.

{ University of Toronto | Continue reading }

Being ostracized or spurned is just like slamming your hand in a door. To the brain, pain is pain, whether it’s social or physical.

{ Bloomberg Businessweek | Continue reading }

photo { Edward Steichen, Dolor, 1903 }

brain, neurosciences | October 18th, 2013 12:22 pm

Cursing, researchers say, is a human universal. Every language, dialect or patois ever studied, whether living or dead, spoken by millions or by a single small tribe, turns out to have its share of forbidden speech, some variant on comedian George Carlin’s famous list of the seven dirty words that are not supposed to be uttered on radio or television. […]

Researchers point out that cursing is often an amalgam of raw, spontaneous feeling and targeted, gimlet-eyed cunning. When one person curses at another, they say, the curser rarely spews obscenities and insults at random, but rather will assess the object of his wrath, and adjust the content of the “uncontrollable” outburst accordingly.

Because cursing calls on the thinking and feeling pathways of the brain in roughly equal measure and with handily assessable fervor, scientists say that by studying the neural circuitry behind it, they are gaining new insights into how the different domains of the brain communicate — and all for the sake of a well-venomed retort. […]

“Studies show that if you’re with a group of close friends, the more relaxed you are, the more you swear,” Burridge said.

{ SF Gate/Natalie Angier | Continue reading }

Linguistics, neurosciences | October 11th, 2013 3:07 pm

No one had previously looked specifically at the differing responses in the brain to poetry and prose.

In research published in the Journal of Consciousness Studies, the team found activity in a “reading network” of brain areas which was activated in response to any written material. But they also found that poetry aroused several of the regions in the brain which respond to music. These areas, predominantly on the right side of the brain, had previously been shown as to give rise to the “shivers down the spine” caused by an emotional reaction to music.

{ University of Exeter | Continue reading }

art { Bridget Riley, Arrest 3, 1965 }

music, neurosciences, poetry | October 10th, 2013 11:00 am

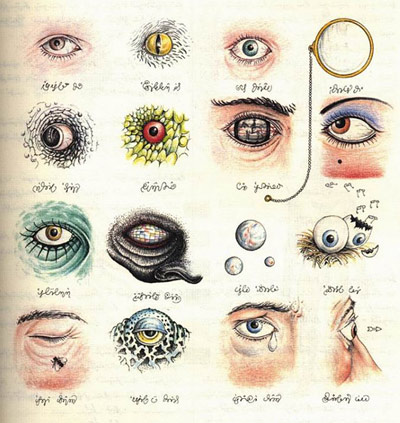

When a healthy person watches a smoothly moving object (say, an airplane crossing the sky), she tracks the plane with a smooth, continuous eye movement to match its displacement. This action is called smooth pursuit. But smooth pursuit isn’t smooth for most patients with schizophrenia. Their eyes often fall behind and they make a series of quick, tiny jerks to catch up or even dart ahead of their target. For the better part of a century, this movement pattern would remain a mystery. But in recent decades, scientific discoveries have lead to a better understanding of smooth pursuit eye movements.

{ Garden of the Mind | Continue reading }

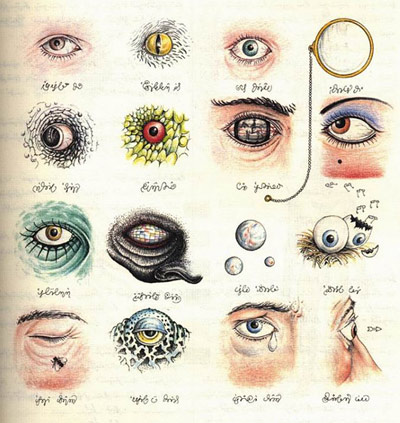

eyes, neurosciences | September 30th, 2013 6:57 pm

Subjective experience of time is just that—subjective. Even individual people, who can compare notes by talking to one another, cannot know for certain that their own experience coincides with that of others. But an objective measure which probably correlates with subjective experience does exist. It is called the critical flicker-fusion frequency, or CFF, and it is the lowest frequency at which a flickering light appears to be a constant source of illumination. It measures, in other words, how fast an animal’s eyes can refresh an image and thus process information.

For people, the average CFF is 60 hertz (ie, 60 times a second). This is why the refresh-rate on a television screen is usually set at that value. Dogs have a CFF of 80Hz, which is probably why they do not seem to like watching television. To a dog a TV programme looks like a series of rapidly changing stills.

Having the highest possible CFF would carry biological advantages, because it would allow faster reaction to threats and opportunities. Flies, which have a CFF of 250Hz, are notoriously difficult to swat. A rolled up newspaper that seems to a human to be moving rapidly appears to them to be travelling through treacle.

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

photo { Paul Andrews }

animals, neurosciences, time | September 24th, 2013 1:51 pm

For a common affliction that strikes people of every culture and walk of life, schizophrenia has remained something of an enigma. Scientists talk about dopamine and glutamate, nicotinic receptors and hippocampal atrophy, but they’ve made little progress in explaining psychosis as it unfolds on the level of thoughts, beliefs, and experiences. Approximately one percent of the world’s population suffers from schizophrenia. Add to that the comparable numbers of people who suffer from affective psychoses (certain types of bipolar disorder and depression) or psychosis from neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease. All told, upwards of 3% of the population have known psychosis first-hand. These individuals have experienced how it transformed their sensations, emotions, and beliefs. […]

There are several reasons why psychosis has proved a tough nut to crack. First and foremost, neuroscience is still struggling to understand the biology of complex phenomena like thoughts and memories in the healthy brain. Add to that the incredible diversity of psychosis: how one psychotic patient might be silent and unresponsive while another is excitable and talking up a storm. Finally, a host of confounding factors plague most studies of psychosis. Let’s say a scientist discovers that a particular brain area tends to be smaller in patients with schizophrenia than healthy controls. The difference might have played a role in causing the illness in these patients, it might be a direct result of the illness, or it might be the result of anti-psychotic medications, chronic stress, substance abuse, poor nutrition, or other factors that disproportionately affect patients.

One intriguing approach is to study psychosis in healthy people. […] This approach is possible because schizophrenia is a very different illness from malaria or HIV. Unlike communicable diseases, it is a developmental illness triggered by both genetic and environmental factors. These factors affect us all to varying degrees and cause all of us – clinically psychotic or not – to land somewhere on a spectrum of psychotic traits. Just as people who don’t suffer from anxiety disorders can still differ in their tendency to be anxious, nonpsychotic individuals can differ in their tendency to develop delusions or have perceptual disturbances. One review estimates that 1 to 3% of nonpsychotic people harbor major delusional beliefs, while another 5 to 6% have less severe delusions. An additional 10 to 15% of the general population may experience milder delusional thoughts on a regular basis.

{ Garden of the Mind | Continue reading }

photo { Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Her Back, 1896 }

mystery and paranormal, neurosciences, psychology | September 18th, 2013 7:24 am

Language is not the only vehicle for many aspects of thought. Many assume that without language it is impossible to think, to remember, to communicate, to have categories/plans/procedures, to have culture and to even have consciousness. Slowly it is being shown that other animals can do many of the things that used to be classed as only-with-language skills. We just do them more effectively with language.

{ Thoughts on Thoughts | Continue reading }

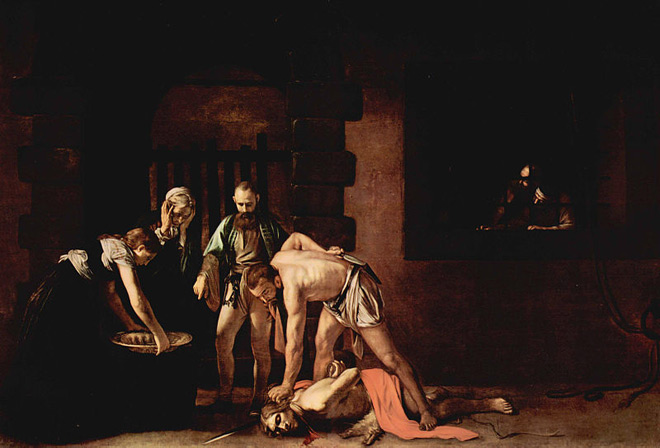

art { Caravaggio, The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, 1608 }

ideas, neurosciences | September 17th, 2013 8:24 pm

Why do we cry when we’re happy?

[The] almond-sized hypothalamus can’t tell the difference between being happy or sad or overwhelmed or stressed. […] All it knows is that it’s getting a strong neural signal from the amygdala, which registers our emotional reactions, and that it must, in turn, activate the autonomic nervous system.

The autonomic nervous system (the “involuntary” nervous system) is divided into two branches: sympathetic (”fight-or-flight”) and parasympathetic (”rest-and-digest”).

Acting via the hypothalamus, the sympathetic nervous system is designed to mobilize the body during times of stress. It’s why our heart rate quickens, why we sweat, why we don’t feel hungry.

The parasympathetic nervous system, on the other hand, essentially calms us back down. The parasympathetic nervous system does something funny, too. Connected to our lacrimal glands (better known as tear ducts), activation of parasympathetic receptors by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine results in tear production. […]

I distinctly remember the feelings of sudden, intense relief. Of happiness. Of weightlessness. Of my heart rate slowing and my parasympathetic nervous system taking over. And, apparently, of acetylcholine synapsing onto lacrimal gland receptors, and of tears pouring down my make-up’d cheeks.

But from a psychological standpoint—beyond the neurotransmitters and stress and hormones—why do we cry at all?

A decade-old theory by Miceli and Castelfranchi proposes that all emotional crying arises from the notion of perceived helplessness, or the idea that one feels powerless when one can’t influence what is going on around them.

{ Gaines, on Brains | Continue reading }

neurosciences | August 30th, 2013 2:03 pm

Some memory exercises focus on long-term memory. Two of these are called retrieval practice and elaboration. […]

One way to elaborate is to generate an explanation for why a fact or concept is true (or false). Another way is to self-explain. Simply explain to yourself how the new ideas you’re learning relate to each other, or explain how the new ideas relate to information you already know. Still another is to make a concept map. […]

Retrieval practice is the activity of recalling information you have already committed to memory. You can practice retrieving information by simply trying to recall everything you’ve read or learned about a subject. Or, you can use the self-test approach. Self-testing means that you create questions about the subject and answer them yourself. […]

A recent study published in Science magazine suggests that retrieval practice works surprisingly well. […]

1. Retrieval practice helps you remember more information than elaboration.

2. Retrieval practice helps you understand the information better than elaboration.

{ Global Cognition | Continue reading }

guide, memory | August 30th, 2013 1:55 pm

Researchers at the University of Kentucky were interested in the link between low glucose levels and aggressive behavior… […]

When you go several hours without eating, your blood sugar drops. Once it falls below a certain point, glucose-sensing neurons in your ventromedial hypothalamus, a brain region involved in feeding, are notified and activated resulting in level fluctuations of several different hormones. Ghrelin, a hormone that increases expression when blood sugar gets low and stimulates appetite through actions of the hypothalamus, has been shown to block the release of the neurotransmitter serotonin. The serotonin system is incredibly complex and contributes to a number of different central nervous system functions. One of the many hats this neurotransmitter wears is modulation of emotional state, including aggression. […]

If you have a predisposition to aggression, low serotonin levels circulating in your brain may lead to altered communications between brain regions that wrangle aggressive behavior.

{ Synaptic Scoop | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, neurosciences, psychology | August 19th, 2013 5:02 pm

At this very moment, your eyes and brain are performing an astounding series of coordinated operations.

Light rays from the screen are hitting your retina, the sheet of light-sensitive cells that lines the back wall of each of your eyes. Those cells, in turn, are converting light into electrical pulses that can be decoded by your brain.

The electrical messages travel down the optic nerve to your thalamus, a relay center for sensory information in the middle of the brain, and from the thalamus to the visual cortex at the back of your head. In the visual cortex, the message jumps from one layer of tissue to the next, allowing you to determine the shape and color and movement of the thing in your visual field. From there the neural signal heads to other brain areas, such as the frontal cortex, for yet more complex levels of association and interpretation. All of this means that in a matter of milliseconds, you know whether this particular combination of light rays is a moving object, say, or a familiar face, or a readable word. […]

This post is about a question that’s long been debated among scientists and philosophers: At what point in that chain of operations does the visual system begin to integrate information from other systems, like touches, tastes, smells, and sounds? What about even more complex inputs, like memories, categories, and words?

We know the integration happens at some point. If you see a lion running toward you, you will respond to that sight differently depending on if you are roaming alone in the Serengeti or visiting the zoo. Even if the two sights are exactly the same, and presenting the same optical input to your retinas, your brain will use your memories and knowledge to put your vision into context

{ Virginia Hughes/National Geographic | Continue reading }

photo { Harry Callahan }

eyes, neurosciences | August 15th, 2013 8:45 am

Infants seem unable to ‘think to themselves’ and instead ‘talk to themselves‘ when solving problems, usually vocalising the most tricky or novel aspects of the situation. As we grow, we develop the ability to internalise this speech, and can eventually have a purely internal monologue.

Understanding inner speech is also important because it becomes distorted in psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia.

People with psychosis can experience effects like ‘thought insertion’, where they experience external thoughts being inserted into their stream of consciousness, or ‘thought withdrawal’, where thoughts seem to be removed from the mind.

This suggests that there must be something that the brain uses to identify thoughts as self-generated, and that this perhaps breaks down in psychosis, so we can have the uncanny experience of having thoughts that don’t seem to be our own.

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading }

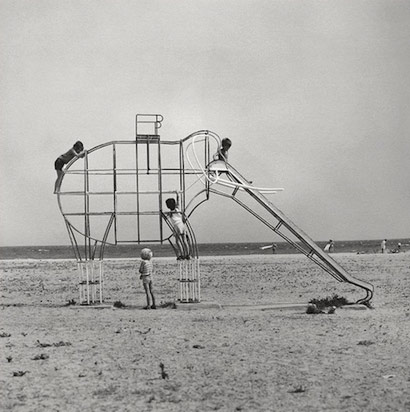

photo { Francesc Català-Roca, Elephant Slide, 1975 }

neurosciences, psychology | June 25th, 2013 11:00 am