As long as the hand that rocks the cradle is mine

For a common affliction that strikes people of every culture and walk of life, schizophrenia has remained something of an enigma. Scientists talk about dopamine and glutamate, nicotinic receptors and hippocampal atrophy, but they’ve made little progress in explaining psychosis as it unfolds on the level of thoughts, beliefs, and experiences. Approximately one percent of the world’s population suffers from schizophrenia. Add to that the comparable numbers of people who suffer from affective psychoses (certain types of bipolar disorder and depression) or psychosis from neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease. All told, upwards of 3% of the population have known psychosis first-hand. These individuals have experienced how it transformed their sensations, emotions, and beliefs. […]

There are several reasons why psychosis has proved a tough nut to crack. First and foremost, neuroscience is still struggling to understand the biology of complex phenomena like thoughts and memories in the healthy brain. Add to that the incredible diversity of psychosis: how one psychotic patient might be silent and unresponsive while another is excitable and talking up a storm. Finally, a host of confounding factors plague most studies of psychosis. Let’s say a scientist discovers that a particular brain area tends to be smaller in patients with schizophrenia than healthy controls. The difference might have played a role in causing the illness in these patients, it might be a direct result of the illness, or it might be the result of anti-psychotic medications, chronic stress, substance abuse, poor nutrition, or other factors that disproportionately affect patients.

One intriguing approach is to study psychosis in healthy people. […] This approach is possible because schizophrenia is a very different illness from malaria or HIV. Unlike communicable diseases, it is a developmental illness triggered by both genetic and environmental factors. These factors affect us all to varying degrees and cause all of us – clinically psychotic or not – to land somewhere on a spectrum of psychotic traits. Just as people who don’t suffer from anxiety disorders can still differ in their tendency to be anxious, nonpsychotic individuals can differ in their tendency to develop delusions or have perceptual disturbances. One review estimates that 1 to 3% of nonpsychotic people harbor major delusional beliefs, while another 5 to 6% have less severe delusions. An additional 10 to 15% of the general population may experience milder delusional thoughts on a regular basis.

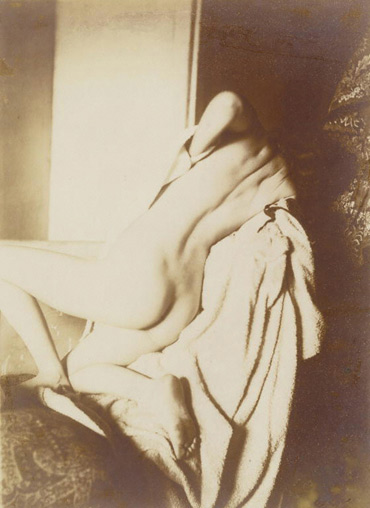

photo { Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Her Back, 1896 }