By my troth, Nerissa, my little body is aweary of this great world

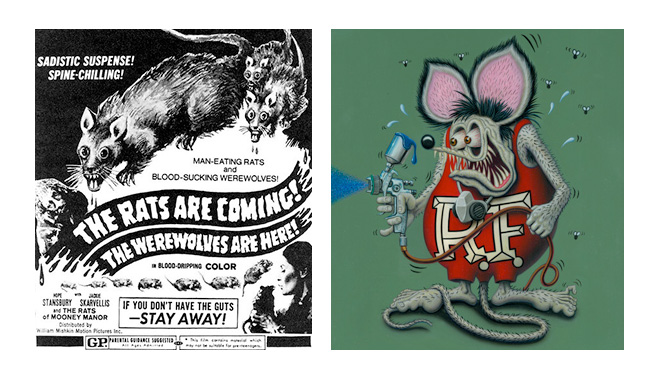

In “Rat Ethics” I am primarily concerned with moral arguments about the rat, in particular, Rattus norvegicus. I argue that there is a complex bias against the animal which reduces it to ‘a pest, vermin, or mischievous’. This predominant bias against rats is a product of cultural stereotyping rather than objective reasoning. A cultural and philosophical examination of the rat can expose and provide grounds for rejecting this bias. I argue that the three main types of rats we encounter (i.e., liminal, research, companion) should be given full moral consideration and determine certain basic moral rights which are distinct to each encounter. I examine the Norway rat from a historical, cultural, philosophical, and practical perspective. I conclude that we must re-evaluate our moral relations with this animal and democratically support the basic rights its moral liberation demands. The fundamental rights of all rats are: 1) the moral right to have reasonable consideration, and 2) the moral right to freedom from unnecessary suffering. Further, contract-based rights are suggested for companion rats, which take the form of additional regulation regarding breeders, retailers, and consumers.

images { ad for The Rats Are Coming! The Werewolves Are Here!, 1972 | Rat Fink by Adam Cruz }