genes

A massive genetics study relying on fMRI brain scans and DNA samples from over 20,000 people has revealed what is claimed as the biggest effect yet of a single gene on intelligence – although the effect is small.

There is little dispute that genetics accounts for a large amount of the variation in people’s intelligence, but studies have consistently failed to find any single genes that have a substantial impact. Instead, researchers typically find that hundreds of genes contribute.

Following a brain study on an unprecedented scale, an international collaboration has now managed to tease out a single gene that does have a measurable effect on intelligence. But the effect – although measurable – is small: the gene alters IQ by just 1.29 points.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

related { Niceness is at least partly in the genes }

genes | April 17th, 2012 10:35 am

Scientists are increasingly finding that depression and other psychological disorders can be as much diseases of the body as of the mind. (…)

Scientists are finding that the same changes to chromosomes that happen as people age can also be found in people experiencing major stress and depression.

The phenomenon, known as “accelerated aging,” is beginning to reshape the field’s understanding of stress and depression not merely as psychological conditions but as body-wide illnesses in which mood may be just the most obvious symptom.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

genes, psychology, science | April 13th, 2012 5:00 am

Pseudogenes are genes that used to have a function, but no longer do. If a gene contributes to an important function for the organism, offspring with deleterious mutations that ruin the gene will have lower fitness, and as a result won’t have as many offspring, if any at all. That mutated gene will likely not go to fixation (become prominent in the population). On the other hand, if the gene used to have a function, but no longer do, then mutations affecting the gene won’t be deleterious. (…)

Examples where pseudogenization is coupled to function is rare. A new study published in PNAS links genes that code for taste receptors to specific dietary changes in carnivorous mammals. Basically, animals that do not eat sweets don’t have receptors for sweetness (e.g., cats), and animals that swallows their food whole have no receptors for umami (e.g., sea lions, dolphins).

{ Pleiotropy | Continue reading }

artwork { Darick Maasen }

animals, genes | March 27th, 2012 1:08 pm

While sex purges our genome of harmful mutations and pushes biodiversity, it’s a costly exercise for the average organism. (…)

Their new estimates for the origins of reliable eukaryotic fossils now rest at 1.78 to 1.68 billion years ago, and this is where we must currently park the idea of when sex first became popular.

The age-old question that follows is why did sexual reproduction begin? Why didn’t life just keep evolving through cloning and asexual budding systems? (…)

Sex is not an efficient way of sharing genes. When we mate sexually we combine only 50% of our genetic material with our partner’s, whereas asexually budding organisms have 100% of their genetic material carried into the next generation. And Otto highlights what biologists call the ‘cost’ of sex, in that sexually reproducing organisms need to produce twice as many offspring as asexual organisms or they lose out in the population race.

Despite these drawbacks, evolution has shaped the living world in such a way that few large creatures today actually reproduce asexually (only about 0.1% of all living organisms, excluding bacteria). Sex generates variation, and that is certainly a good thing when dealing with constant and unpredictable changes in our environment.

{ Cosmos | Continue reading }

genes, science, sex-oriented | March 20th, 2012 12:51 pm

According to a paper just published (but available online since 2010), we haven’t found any genes for personality.

The study was a big meta-analysis of a total of 20,000 people of European descent. In a nutshell, they found no single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with any of the “Big 5″ personality traits of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness. There were a couple of very tenuous hits, but they didn’t replicate.

Obviously, this is bad news for people interested in the genetics of personality.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

image { Pole Edouard }

genes, psychology | March 19th, 2012 12:15 pm

We now have the potential to banish the genes that kill us, that make us susceptible to cancer, heart disease, depression, addictions and obesity, and to select those that may make us healthier, stronger, more intelligent. (…)

During that year, fertility clinics across the country have begun to take advantage of the technology’s latest tools. They are sending cells from embryos conceived here through in vitro fertilization (IVF) to private U.S. labs equipped to test them rapidly for an ever-growing list of genetic disorders that couples hope to avoid.

Recent breakthroughs have made it possible to scan every chromosome in a single embryonic cell, to test for genes involved in hundreds of “conditions,” some of which are clearly life-threatening while others are less dramatic and less certain – unlikely to strike until adulthood if they strike at all.

And science is far from finished. On the horizon are DNA microchips able to analyze more than a thousand traits at once, those linked not just to a child’s health but to enhancements – genes that influence height, intelligence, hair, skin and eye color and athletic ability.

{ The Globe and Mail | Continue reading }

photo { Loretta Lux }

genes, kids, uh oh | January 11th, 2012 11:52 am

Biologists had long known that DNA was built out of four molecules: adenine, guanine, thymine and cytosine. They assumed that these molecules occurred in equal quantity and dismissed any measurements that hinted otherwise as experimental errors.

Chargaff showed through careful measurement that this assumption was wrong. He found that the amount of adenine equalled that of thymine and the amount of guanine equalled that of cytosine but these were not equal to each other. (…)

Chargaff went on to discover that an approximate version of his rule also holds for most (but not all) single-stranded DNA. (…) Chargaff’s rules are important because they point to a kind of “grammar of biology,” a set of hidden rules that govern the structure of DNA. (…)

But in the 60 years since Chargaff discovered his invariant patterns, no others have emerged. Until now.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

artwork { Robin Williams }

genes, science | December 9th, 2011 12:02 pm

From time to time, you will see news of a lobster being caught with some unusual color, like orange, blue, or calico. (…) What determines color in crustaceans generally? It’s a complicated mix.

The most dramatic color variants are caused by genetics. (…)

Bowman investigated this in crayfish decades ago by placing crayfish in normal tanks, tanks painted black, and tanks painted white. Crayfish placed in black tanks had more red coloration, and those in the white tanks, more white coloration. Bowman also noted that animals that had become adapted to the bright white tanks did not darken up again after being placed into black surroundings. There are limits to how flexible the color changes are.

{ Marbled Crayfish News & Views | Continue reading }

animals, colors, genes, science | November 22nd, 2011 12:25 pm

It’s weird to think that tens of thousands of years ago, humans were mating with different species—but they were. That’s what DNA analyses tell us. When the Neanderthal genome was sequenced in 2010, it showed that as much as 1 to 4 percent of the DNA of non-Africans might have been inherited from Neanderthals.

Scientists also announced last year that our ancestors had mated with another extinct species, and this week, more evidence is showing how widespread that interbreeding was.

We know little about this extinct species. In fact, we don’t even have a scientific name for it; for now, the group is simply known as the Denisovans.

{ Smithsonian Magazine | Continue reading }

flashback, genes, mystery and paranormal, science | November 4th, 2011 11:10 am

Whether you were happy with life as a teenager could be down to a certain gene, says a new study.

In a large study of American adolescents, teens who carried the long form of the 5HTTLPR locus were more likely to say they were satisfied or very satisified with their lives (at age 18 to 26). People with two long variants were the most cheerful, with short/long carriers in the middle and short/short being the least so. (…)

This study is the latest in a long, long line of attempts to correlate 5HTTLPR with happiness, depression, stress and so on. A few months ago I discussed the history of this busy little gene and covered a meta-analysis of no fewer than 54 papers which claimed that there was indeed a link, with the short allele increasing the risk of depression in response to stressful events.

However many studies failed to find one, and worryingly the three largest studies were all negative which is a classic tell-tale sign of publication bias.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

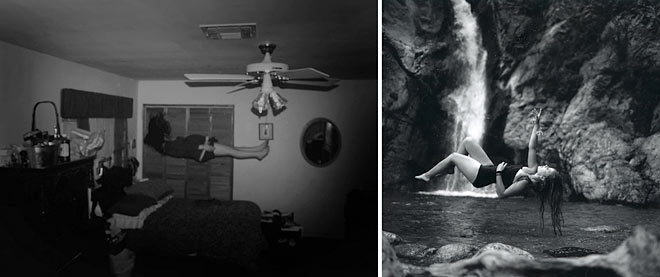

photos { 1. Erica Segovia | 2. Maggie Lochtenberg }

genes, kids, photogs | October 27th, 2011 8:19 am

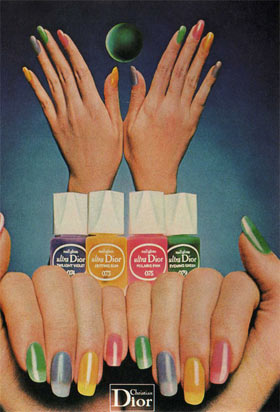

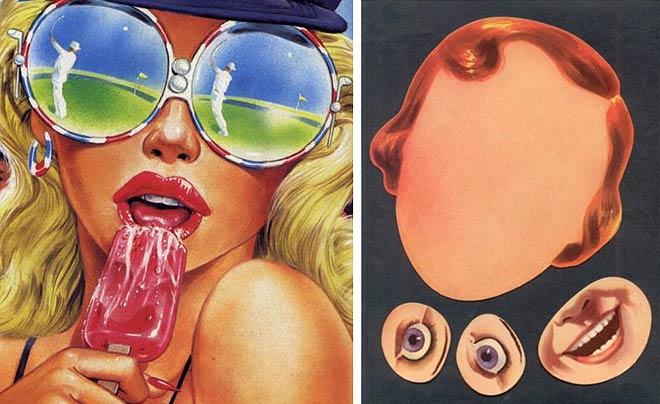

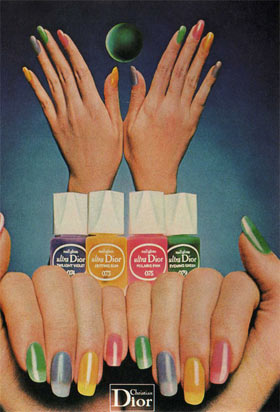

colors, genes, visual design | September 28th, 2011 10:29 am

In December 2010, two independent laboratories have demonstrated that a full genome-wide analysis of the fetus could be performed from a sample of maternal blood, making fetal diagnostic testing possible in the future for any known genetic condition. The convergence of cffDNA (cell-free fetal DNA) testing with low cost genomic sequencing will enable prospective parents to have relatively inexpensive access to a wide range of genetic information about their fetus from as early as seven weeks gestation.

This article examines a range of ethical, legal and social implications associated with introducing NIPD (non-invasive prenatal diagnosis) into prenatal practice.

{ SSRN | Continue reading }

genes, health, kids | September 20th, 2011 8:05 am

Genes determine 50 percent of the likelihood that you will vote. Half of your altruism. One-quarter of your financial decisions. How do we know? Twin studies.

Researchers compare some behavior or trait in a set of pairs of monozygotic (identical) twins and a set of pairs of dizygotic (fraternal) twins. In theory, the siblings in each pair have been raised in the same way—i.e., they have “nurture” in common. But their “natures” might be different: Identical twins come from the same sperm and egg and are assumed to share their entire genomes; fraternal twins match up at only about half their genes. So if the pairs of monozygotic twins tend to share a trait more often than the pairs of dizygotic twins—be it the likelihood they will vote, a tendency toward altruism, or a strategy for managing their financial portfolios—the difference can be chalked up to genetics.

Some call this approach beautiful in its simplicity, but critics say it’s crude, potentially misleading, and based on an antiquated view of genetics. The implications of the studies are also just a little bit dangerous, because they suggest, for example, that some people just aren’t cut out for being nice to one another.

The idea of using twins to study the heritability of traits was the brainchild of the 19th-century British intellectual Sir Francis Galton. He’s not exactly the progenitor you might want for your scientific methods. Galton coined the term “eugenics” and was the inspiration for the push to manipulate human evolution through selective breeding. The movement eventually gave us forced sterilization and the most offensive passage in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court (and that’s really saying something): “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” (…)

Twin studies rest on two fundamental assumptions: 1) Monozygotic twins are genetically identical, and 2) the world treats monozygotic and dizygotic twins equivalently (the so-called “equal environments assumption”). The first is demonstrably and absolutely untrue, while the second has never been proven. (…)

Twin studies also rely on the false assumption that genetics are constant throughout one’s lifetime. Mutations and environmental factors cause measurable changes to the genome as life progresses. Charney cites the example of exercise, which can accelerate the formation of new neurons and potentially increase genetic variation among individual brain cells. By the time a pair of twins reaches middle age, it’s very difficult to make any assumptions whatsoever about the similarity of their genes.

{ Slate | Continue reading }

controversy, genes, science | August 29th, 2011 2:58 pm

Mothers who inherited either one or two copies of a particular form of the dopamine D2 receptor gene, dubbed DRD2, cited sharp rises in spanking, yelling and other aggressive parenting methods for six to seven months after the onset of the economic recession in December 2007, sociologist Dohoon Lee of New York University reported August 22 at the American Sociological Association’s annual meeting.

Hard-line child-rearing approaches then declined for a few months and remained stable until a second drop to pre-recession levels started around June 2009, the research showed.

Mothers who didn’t inherit the gene variant displayed no upsurge in aggressive parenting styles after the recession started, Lee and his colleagues found.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

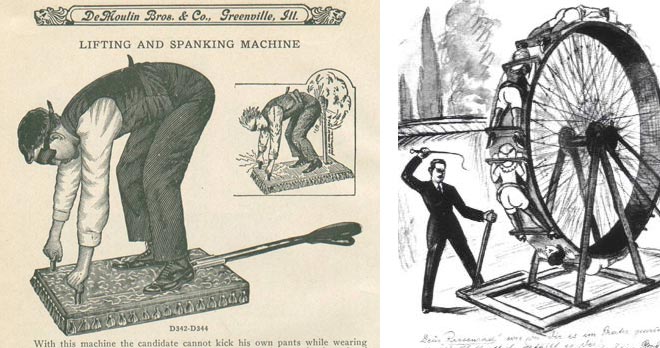

images { 1 | 2 }

economics, genes, kids | August 29th, 2011 2:58 pm

University of Minnesota Medical School and College of Biological Sciences researchers have made a key discovery showing that male sex must be maintained throughout life.

The research team, led by Drs. David Zarkower and Vivian Bardwell of the U of M Department of Genetics, Cell Biology and Development, found that removing an important male development gene, called Dmrt1, causes male cells in mouse testis to become female cells.

In mammals, sex chromosomes (XX in female, XY in male) determine the future sex of the animal during embryonic development by establishing whether the gonads will become testes or ovaries.

“Scientists have long assumed that once the sex determination decision is made in the embryo, it’s final,” Zarkower said. “We have now discovered that when Dmrt1 is lost in mouse testes – even in adults – many male cells become female cells and the testes show signs of becoming more like ovaries.”

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

genders, genes, science | July 20th, 2011 7:27 pm

It is well recognized that there are consistent differences in the psychological characteristics of boys and girls; for example, boys engage in more ‘rough and tumble’ play than girls do.

Studies also show that children who become gay or lesbian adults differ in such traits from those who become heterosexual – so-called gender nonconformity. Research which follows these children to adulthood shows that between 50 to 80 per cent of gender nonconforming boys become gay, and about one third of such girls become lesbian. (…)

The team followed a group of 4,000 British women who were one of a pair of twins. They were asked questions about their sexual attractions and behavior, and a series of follow up questions about their gender nonconformity. In line with previous research, the team found modest genetic influences on sexual orientation (25 per cent) and childhood gender nonconformity (31 per cent).

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

images { 1 | 2 }

genders, genes, kids, relationships | July 11th, 2011 4:10 pm

Each of us receives, on average, 60 mutations in our genome from our parents, a new study has revealed — far fewer than previously estimated. (…)

“We had previously estimated that parents would contribute an average of 100-200 mistakes to their child. Our genetic study, the first of its kind, shows that actually much fewer mistakes — or mutations — are made.” It is these mistakes or “mutations” that help us evolve.

The geneticists from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, who co-led the study with scientists from Montreal and Boston, also found that the percentage of mutations from each parent varies in every person.

{ Wired UK | Continue reading }

genes, science | July 8th, 2011 9:25 am

Last year, a team of NASA-funded scientists claimed to have found bacteria that could use arsenic to build their DNA, making them unlike any form of life known on Earth. That didn’t go over so well. One unfortunate side-effect of the hullabaloo over arsenic life was that people were distracted from all the other research that’s going on these days into weird biochemistry. Derek Lowe, a pharmaceutical chemist who writes the excellent blog In the Pipeline, draws our attention today to one such experiment, in which E. coli is evolving into a chlorine-based form of life.

Scientists have been contorting E. coli in all sorts of ways for years now to figure out what the limits of life are. Some researchers have rewritten its genetic code, for example, so that its DNA can encode proteins that include amino acids that are not used by any known organism.

Others have been tinkering with the DNA itself. In all living things, DNA is naturally composed of four compounds, adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine. Thymine is a ring of carbon and nitrogen atoms, with oxygen and hydrogens atoms dangling off the sides. Since the 1970s, some scientists have tried to swap thymine for other molecules. This compound is called 5-chlorouracil, the “chloro-” referring to the chlorine marked here in red. No natural DNA contains chlorine.

{ Carl Zimmer/Discover | Continue reading }

related { The end of E. Coli }

genes, science | July 8th, 2011 9:05 am

Scientists have untangled some — but not nearly all — of the mysteries behind our love and hatred of certain foods. (…)

Our tongues perceive only five basic tastes: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and “umami,” the Japanese word for savory. (…)

“We as primates are born liking sweet and disliking bitter,” said Marcia Pelchat, who studies food preferences at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia. The theory is that we’re hard-wired to like and dislike certain basic tastes so that the mouth can act as the body’s gatekeeper.

Sweet means energy; sour means not ripe yet. Savory means food may contain protein. Bitter means caution, as many poisons are bitter. Salty means sodium, a necessary ingredient for several functions in our bodies. (By the way, those tongue maps that show taste buds clumped into zones that detect sweet, bitter, etc.? Very misleading. Taste receptors of all types blanket our tongues — except for the center line — and some reside elsewhere in our mouths and throats.)

Researchers have found only one major human gene that detects sweet tastes, but we all have it. By contrast, 25 or more bitter receptor genes may exist, but combinations vary by person. Some genetic connections are so strong that scientists can predict fairly accurately how people will react to certain bitter tastes by looking at their DNA.

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants, genes, science | April 28th, 2011 8:12 pm

Suicide Gene Identified

The study evaluated the entire genomes of patients with bipolar disorder who had attempted suicide (n=1201) and those who had not (n=1497). In total, there were more than 2500 regions located on various chromosomes that showed significant associations with suicidal behavior. The strongest association was with a region on chromosome 2 containing the ACP1 gene. This gene encodes for a signaling protein (tyrosine phosphatase) produced in the brain.

{ BrainBlogger | Continue reading }

photo { Sophia Wallace }

genes, science | April 12th, 2011 3:00 pm