science

In the mid 1920s, Berger invented the electroencephalagraph (EEG), a technique for measuring the electrical activity of brains. Unfortunately, Berger didn’t understand electricity very well, so didn’t have a clear understanding of what his recordings might mean. But he revolutionized the study of human brains.

Perhaps nowhere was Berger’s invention put to greater use than in the study of sleep. Before that, what did we know of brains while we slept? (…)

Berger’s invention continues to deepen our understanding of sleep, nearly a century after its invention, as shown by a new paper by KcKinney and colleagues.

{ NeuroDojo | Continue reading }

related { Short on sleep, the brain optimistically favors long odds }

painting { John Kacere }

science, sleep | March 10th, 2011 5:36 pm

{ A small number of randomly selected legislators should make parliaments more effective, say a group of IgNobel prize-winning scientists. | The Physics arXiv Blog | full story | Photo: Tim Davis }

ideas, science | March 10th, 2011 5:35 pm

The brain does not stop developing until we are in our 30s or 40s – meaning that many people will still have something of the teenager about them long after they have taken on the responsibilities of adulthood.

The finding, from University College London, could perhaps help explain why seemingly respectable adults sometimes just can’t resist throwing a tantrum or sulking until they get their own way.

The discovery that the part of the brain key to getting on with others takes decades to fully form could perhaps also explain why some people are socially awkward well past their teenage years.

Neuroscientist Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore said: ‘Until about 10 years ago, it was pretty much assumed that the human brain stops developing in early childhood.

‘But we now know that is far from the truth, in fact most regions of the human brain continue to develop for many decades.

{ Daily Mail | Continue reading }

photo { Fette Sans }

neurosciences, time | March 10th, 2011 5:25 pm

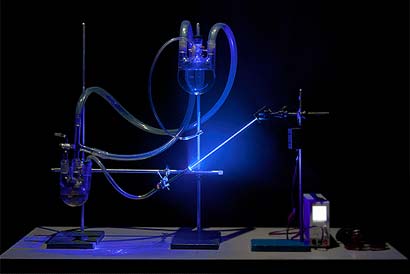

…everyone will agree that there are no restraints against the formation of organic compounds from non-organic reactants. This has been demonstrated since 1952 when Stanley Miller and Harold Urey did their famous experiment. (…) In fact, organic compounds have been found in the oddest places; Titan, nebula, and meteorites.

Now, the question, of course, is how did these disparate pieces come together and form the living system we see today?

{ Cassandra’s Tears | Continue reading }

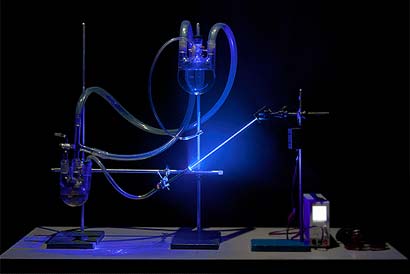

The Miller and Urey experiment was an experiment that simulated hypothetical conditions thought at the time to be present on the early Earth, and tested for the occurrence of chemical origins of life.

Specifically, the experiment tested Oparin’s and Haldane’s hypothesis that conditions on the primitive Earth favored chemical reactions that synthesized organic compounds from inorganic precursors. Considered to be the classic experiment on the origin of life, it was conducted in 1952 and published in 1953.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

installation { Dimension/Next, Miller-Urey Bong, 2010 | Dimension/Next specifically proposes that the addition of C21H30O2 to the existing Miller-Urey hypothesis of CH4 + NH3 + H2 + H20 has a high chance of producing exceptional results. }

flashback, science | March 10th, 2011 5:10 pm

Two leading neuroscientists, Christof Koch and Susan Greenfield, disagree about the activity that takes place in the brain during subjective experience.

How brain processes translate to consciousness is one of the greatest un-solved questions in science. Although the scientific method can delineate events immediately after the big bang and uncover the biochemical nuts and bolts of the brain, it has utterly failed to satisfactorily explain how subjective experience is created.

As neuroscientists, both of us have made it our life’s goal to try to solve this puzzle. We share many common views, including the important acknowledgment that there is not a single problem of consciousness. Rather, numerous phenomena must be explained—in particular, self-consciousness (the ability to examine one’s own desires and thoughts), the content of consciousness (what you are actually conscious of at any moment), and how brain processes relate to consciousness and to nonconsciousness.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading | PDF | More: Our intuitions about consciousness in other beings and objects reveal a lot about how we think }

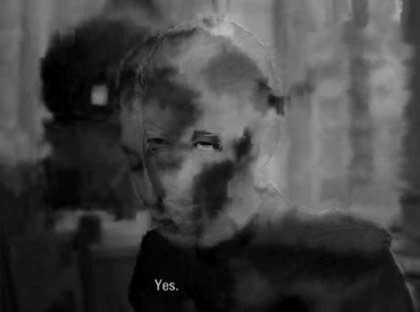

mixed media { Douglas Gordon, Straight to Hell, 2011 }

brain, ideas | March 8th, 2011 7:06 pm

A 44-year-old woman with a rare form of brain damage can literally feel no fear, according to a case study published yesterday in the journal Current Biology. Referred to as SM, she suffers from a genetic condition called Urbach-Wiethe Disease. The condition is extremely rare, with fewer than 300 reported cases since it was first described in 1929, and is caused by a mutation in a gene on chromosome 1, which encodes an extracellular matrix protein.

{ Neurophilosophy | Continue reading }

brain, science | March 8th, 2011 7:01 pm

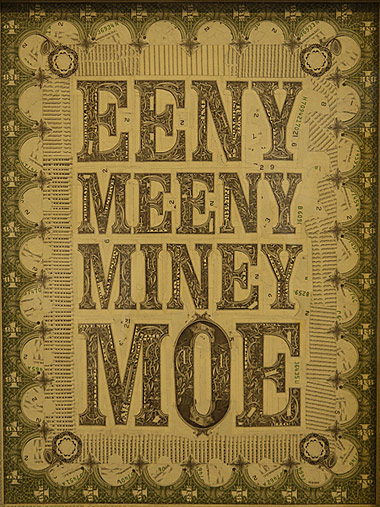

A psych study asked people to think of someone they felt guilty toward, or made them imagine feeling guilty toward someone (e.g., slacking off on a joint project, or being careless with something borrowed). Researchers then had these guilty folks divide up money between themselves, the victim, and a third party (e.g., a deserving charity or random person). Compared to controlled conditions, such people give more money to the victim, but at the expense of the third party, not themselves.

{ OvercomingBias | Continue reading }

collage { Mark Wagner }

psychology, relationships | March 8th, 2011 7:00 pm

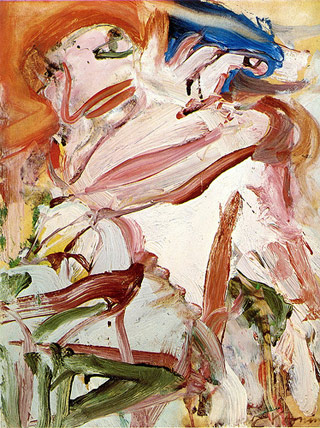

Does monocular viewing affect judgement of art? According to a 2008 paper by Finney and Heilman it does. The two researchers from the University of Florida inspired by previous studies investigating the effect of monocular viewing on performance on visual-spatial and verbal memory tasks, attempted to see what the results would be in the case of Art.

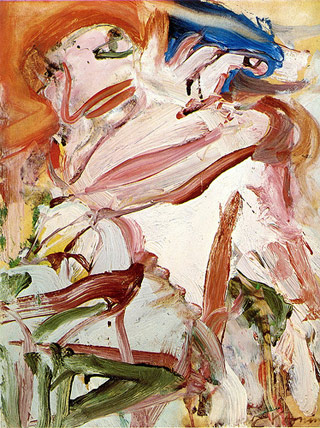

In particular, they recruited 8 right-eye dominant subjects (6 men and 2 women) with college education and asked them to view monocularly on a colour computer screen 10 painting with the right eye and another 10 with the left. None of the subjects was familiar with the presented paintings. Overall, each subject viewed 5 abstract expressionist and 5 impressionist paintings with each eye. (…)

Monocular viewing had significant effects only in paintings in the abstract expressionist style. Impressionist paintings yielded no differences.

{ Nou Stuff | Continue reading }

painting { Willem de Kooning, Figure with Red Hair 1967 }

art, eyes, science | March 8th, 2011 7:00 pm

Humans experience pleasure from a variety of stimuli, including food, money, and psychoactive drugs. Such pleasures are largely made possible by a brain chemical called dopamine, which activates what is known as the mesolimbic system — a network of interconnected brain regions that mediate reward. Most often, rewarding stimuli are biologically necessary for survival (such as food), can directly stimulate activity of the mesolimbic system (such as some psychoactive drugs), or are tangible items (such as money).

However, humans can experience pleasure from more abstract stimuli, such as art or music, which do not fit into any of these categories. Such stimuli have persisted across countless generations and remain important in daily life today. Interestingly, the experience of pleasure from these abstract stimuli is highly specific to cultural and personal preferences.

{ BrainBlogger | Continue reading }

collage { Eric Foss }

brain, music, neurosciences | March 8th, 2011 3:14 pm

On January 14th, a 39-year-old computer engineer was admitted to Princeton University Hospital in New Jersey with nagging, flu-like symptoms. The man was nauseated, suffering from severe joint pains, wracked by a strange, convulsive trembling in his legs. Doctors at the hospital tried one treatment after another but Xiaoye Wang only became weaker.

Finally, a nurse at the hospital stepped hesitantly forward. She remembered a 1995 case in China in which a student at Beijing University became mysteriously ill. The cause was eventually found to be poisoning by the toxic element thallium. The young woman received a life-saving antidote although she suffered lingering disabilities from the attack.

And – as the nurse recalled from the highly publicized case – the student’s symptoms were eerily similar to Wang’s. (…) The Princeton doctors were dubious about a fairly exotic poison use, but they were running out of ideas. So they agreed to send Wang’s blood and urine samples out of state. And to their shock, the tests proved the nurse right. The lab had discovered a shockingly high level of thallium in Wang’s body. (…)

Thallium is a dangerous and carefully regulated poison, once widely available but mostly found in laboratories these days. “It’s either attempted suicide or homicide,” said Steven Marcus, head of the poison control center. He added that he knew of only one good antidote for thallium poisoning, a medication called Prussian Blue.

Rather ironically, the antidote’s name derives from another famously lethal substance. Prussian Blue refers to cyanide (a component of the medication) which can be used to produce a royal blue pigment. Some cyanide formulas are very deadly, notably hydrogen cyanide or potassium cyanide. But mixed into the tidy antidote formula (brand name Radiogardase) cyanide merely becomes part of a chemical chain that wraps itself around thallium, binding it up, and allowing the body to remove the poison.

By the time, the New Jersey doctors were able to secure the antidote though, it was too late. Wang was deep into a coma; he died on January 26 leaving doctors – and now criminal investigators – to answer the question raised by Steven Marcus. Was it suicide or was it murder?

{ PLoS | Continue reading }

incidents, science | March 8th, 2011 3:10 pm

In January, the shooting of Gabrielle Giffords produced a half dozen bona fide heroes, including Patricia Maisch, a 61-year-old woman who snatched ammunition out of alleged gunman Jared Loughner’s hands as he tried to reload. For good reason, people like these earn our respect and adulation; their grace under pressure strikes us as almost superhuman. Yet as we marvel at their deeds, we’re always left wondering about where, exactly, this composure comes from. Do these people emerge from the womb with sanguine looks on their faces, ready to perform life-saving surgery in the next room if necessary? Or is their coolness something they picked up through life experience? (…)

Let’s start with the “nature” side of the equation. For every one of us, the starting point for cool-headedness comes bundled within our DNA: our innate disposition toward anxiety. It’s never been a secret that anxiousness is partially inherited, but no one knew how much influence our genes threw around until psychiatrist Kenneth Kendler came along. In a 2001 study, Kendler and his colleagues examined 1,200 pairs of male twins, some identical and some fraternal, probing into each brother’s individual phobias. Because all of the twins shared the same upbringing, yet only the identical twins shared the same DNA, Kendler could filter out environmental factors altogether and calculate a pure figure for our genetic susceptibility to anxiety. The answer? Genes account for around 30 percent of our anxiousness.

{ Slate | Continue reading }

genes, psychology, science | March 7th, 2011 6:50 pm

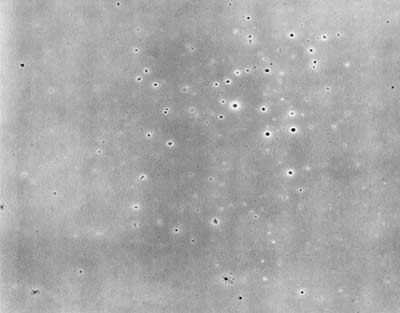

Many a beer drinker will have puzzled over the following: why, when a can of beer is opened, do carbon dioxide bubbles form so slowly. Why not all at once?

The study of bubble formation in carbonated drinks is a relatively new science. In fact, it is only ten years since scientists settled this matter. One group calculated from first principles the rate at which carbon dioxide leaks from solution into a bubble. The answer is slowly. What’s more, it cannot start without some sort of nucleation site.

Then, another group discovered that the primary sources of nucleation are pockets of gas trapped in cellulose fibres in the drink. The news was greeted by the sound of clinking glasses the world over. Problem solved?

Not quite. While most beers and lagers are pressurised with carbon dioxide, some stouts, dark beers such as Guinness, are pressurised by a mixture of carbon dioxide and nitrogen.

They do this because nitrogen forms smaller bubbles giving the drink a smoother, creamier mouth feel. But it also changes the bubble dynamics significantly. The question is why.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

gelatin silver print { Alison Rossiter }

food, drinks, restaurants, science | March 7th, 2011 6:30 pm

We modify our own opinions in line with what other people think, especially our friends and peers.

A problem for psychologists investigating the effect of peer influence is that it can be tricky to tell whether people are simply acquiescing in public, for show, or if their attitudes really have changed.

A new study by a team of psychologists at Harvard University has used an innovative mix of behavioural and brain-scan methods to show that peer influence really can change how people value something, in this case the attractiveness of a face.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

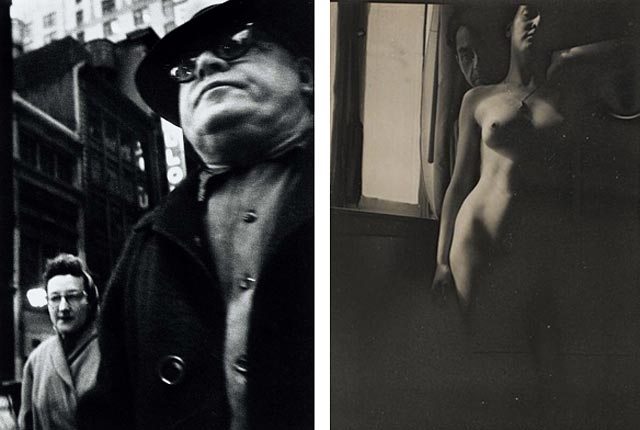

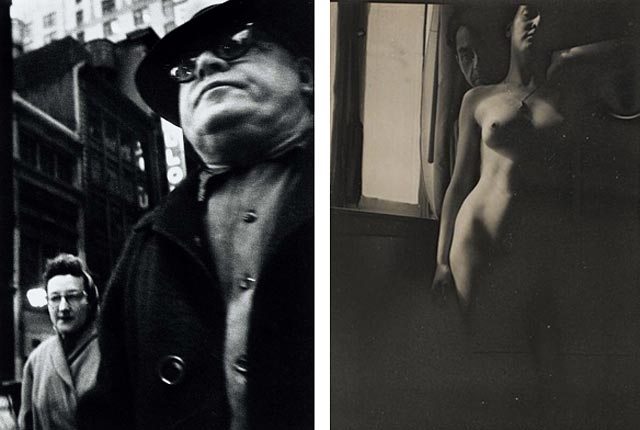

photos { William Klein, Man Foreground, Woman Behind, 1955 | Right: Man Ray, Self-Portrait with Meret Oppenheim, 1933 }

halves-pairs, photogs, psychology, relationships | March 7th, 2011 6:25 pm

David Lane takes great pains to point out that randomness is only one aspect of Darwinism; natural selection, what Jacques Monod (1972) called “necessity”, seems to ensure that evolution has, if no purpose, at least some kind of direction. But if it has a direction, where is it going?

If survival of the fittest is not a tautology, as some critics have claimed (Wilkins 1997), shouldn’t evolution to some extent be predictable? Using evolutionary theory, we can look back into the past and understand how and why certain forms of life evolved. But what can we say about the future?

We need to address this question not simply to reassure people that life is more than just a matter of chance. Predictability goes to the heart of what science is and does. Science can be succinctly defined as the attempt to identify the causes of phenomena. But the process does not stop there. When we think we know what causes a phenomenon, we attempt to use this knowledge to predict other phenomena, and ultimately, by causing them by our own actions.

{ Tikkun | Continue reading }

photo { SW▲MPY }

ideas, science | March 3rd, 2011 7:05 pm

People with full bladders make better decisions.

Researchers discovered the brain’s self-control mechanism provides restraint in all areas at once. They found people with a full bladder were able to better control and “hold off” making important, or expensive, decisions, leading to better judgement. (…)

Dr Mirjam Tuk, who led the study, said that the brain’s “control signals” were not task specific but result in an “unintentional increase” in control over other tasks.

“People are more able to control their impulses for short term pleasures and choose more often an option which is more beneficial in the long run,” she said. (…)

They concluded that people with full bladders were better at holding out for the larger rewards later.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading | Thanks Tim! }

psychology, water | March 3rd, 2011 2:10 pm

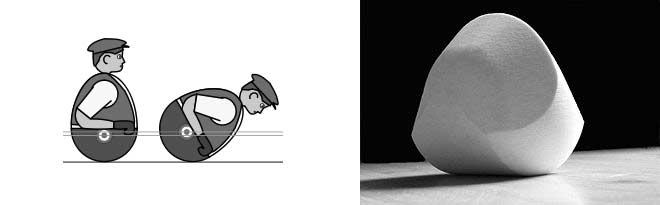

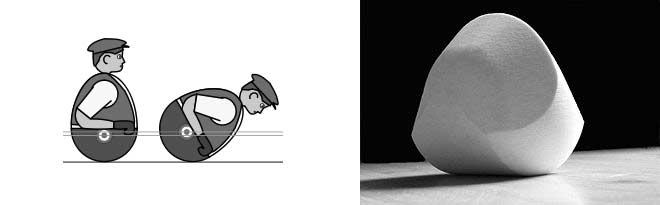

A Gömböc (pronounced [ˈɡømbøts], simplified to Gomboc) is a convex three-dimensional homogeneous body which, when resting on a flat surface, has just one stable and one unstable point of equilibrium. Its existence was conjectured by Russian mathematician Vladimir Arnold in 1995 and proven in 2006 by Hungarian scientists Gábor Domokos and Péter Várkonyi. (…)

The balancing properties of the Gömböc are associated with the “righting response”, their ability to turn back when placed upside down, of shelled animals such as turtles and beetles.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading | Thanks to James T. }

mathematics, technology | March 3rd, 2011 1:02 pm

New findings provide further evidence that abstract concepts are grounded in sensory metaphors. Just as holding a heavy object makes us perceive an issue as being more important, and physical warmth makes us perceive an interpersonal relationship as also being warm, so does touching something tough or tender influence our mental representation of social categories such as sex.

{ Neurophilosophy | Continue reading }

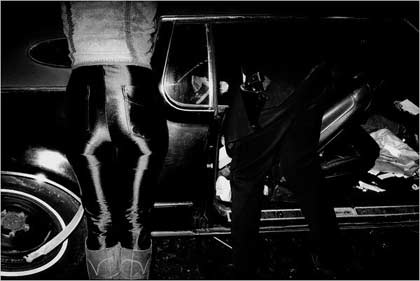

photo { Jill Freedman }

psychology, relationships | March 2nd, 2011 7:20 pm

Researchers looked at whether simple restoration of justice (“an eye for an eye”) is enough for us or if we also want the offender to understand just what they did wrong. (…)

They concluded that simple equalization of suffering is not enough—we also want the offender to know just why they were punished (for their bad or mean-spirited behavior).

{ Keene Trial Consulting | Continue reading }

psychology | March 2nd, 2011 7:10 pm

It’s about Professor Daryl Bem and his cheerful case for ESP.

According to “Feeling the Future,” a peer-reviewed paper the APA’s Journal of Personality and Social Psychology will publish this month, Bem has found evidence supporting the existence of precognition. (…)

Responses to Bem’s paper by the scientific community have ranged from arch disdain to frothing rejection. And in a rebuttal—which, uncommonly, is being published in the same issue of JPSP as Bem’s article—another scientist suggests that not only is this study seriously flawed, but it also foregrounds a crisis in psychology itself. (…)

Over seven years, Bem measured what he considers statistically significant results in eight of his nine studies. In the experiment I tried, the average hit rate among 100 Cornell undergraduates for erotic photos was 53.1 percent. (Neutral photos showed no effect.) That doesn’t seem like much, but as Bem points out, it’s about the same as the house’s advantage in roulette. (…)

“It shouldn’t be difficult to do one proper experiment and not nine crappy experiments,” the University of Amsterdam’s Eric-Jan Wagenmakers, co-author of the rebuttal, says. (…)

Before PSI, Bem made his biggest splash in the nonacademic world with a politically incorrect but weirdly compelling theory of sexual orientation. In 1996, he published “Exotic Becomes Erotic” in Psychological Review, arguing that neither gays nor straights are “born that way”—they’re born a certain way, and that’s what eventually determines their sexual preference.

“I think what the genes code for is not sexual orientation but rather a type of personality,” he explains. According to the EBE theory, if your genes make you a traditionally “male” little boy, a lover of sports and sticks, you’ll fit in with other boys, so what will be exotic to you—and, eventually, erotic—are females. On the other hand, if you’re sensitive, flamboyant, performative, you’ll be alienated from other boys, so you’ll gravitate sexually toward your exotic—males.

EBE is not exactly universally accepted.

{ NY mag | Continue reading }

photos { Irina Werning, Back to the future, Mechi 1990 & 2010, Buenos Aires | more }

controversy, mystery and paranormal, psychology | March 2nd, 2011 7:09 pm

The Kepler observatory was launched into orbit in early 2009. Its mission: to search for planets in solar systems other than our own. Their recent results point to a staggering number of planets that share the galaxy with us, many of which orbit their sun in a habitable temperature zone: between 0 and 100 °C. This means that water-based life such as ourselves would neither freeze nor boil away, assuming that the planet has atmospheric pressure similar to Earth. (…)

Based on the approximate value of 100 billion stars in our galaxy, scientists with Kepler estimate at least 50 billion planets (one out of every two stars is expected to have a planet). And 500 million or so of those planets are in the habitable temperature zone.

{ Berkeley Science Review | Continue reading }

space | March 2nd, 2011 7:00 pm