science

Scientists found that humans exhibit two types of memory. They call one “verbatim trace,” in which events are recorded very precisely and factually. Children have more “verbatim trace,” but as they mature, they develop more and more of a second type of memory: “gist trace,” in which they recall the meaning of an event, its emotional flavor, but not precise facts. Gist trace is the most common cause of false memories, occurring most often in adults. Research shows that children are less likely to produce false memories, because gist trace develops slowly.

{ ScienceDaily | Continue reading }

Psychological scientists have discovered all sorts of ways that false memories get created, and now there’s another one for the list: watching someone else do an action can make you think you did it yourself. (…)

They found that people who had watched a video of someone else doing a simple action — shaking a bottle or shuffling a deck of cards, for example — often remembered doing the action themselves two weeks later.

{ ScienceDaily | Continue reading | Related: People can easily create false memories of their past and a new study shows that such memories can have long-term effects on our behavior. }

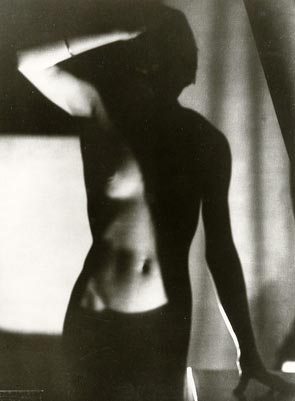

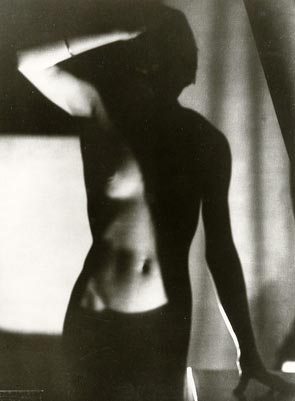

photo { František Drtikol }

brain, kids, psychology, science, time | October 1st, 2010 6:15 pm

Red is a color evoked by light consisting of the longest wavelengths of light discernible by the human eye.

Longer wavelengths than this are called infrared (below red), and cannot be seen by the naked human eye.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

In Judo, for instance, fighters are allocated Blue or White prior to competition, and in Taekwon-Do, the colours are Red and Blue. Boxers often wear multi-coloured or patterned trunks, but the colour of the gloves is often different.

Hill and Barton (2005) demonstrated that in the 2004 Olympic Games Red competitors were significantly more successful than blue competitors in an even contest. Basically, Red doesn’t give you a +10 str, but it will a) tip the bias of the point recorders in your favour; b) increase one’s competitiveness; or c) scare you opponent just enough so that you have an advantage.

Their paper, published in Nature, does not speculate on the cause – a, b, and c are my own speculations. They also found that Red vs. non-red and non-blue also tipped the advantage to the red competitors. It kind of stands to reason – red is a scary colour, it’s a natural marker of many evolutionary elements, and it’s visually arresting , like black.

I thought maybe it has to do with dominance of colour – but Dijkstra and Preenen (2008) demonstrated that in Judo (where competition is between blue v white) there is no relative advantage to blue – which is arguable the more dominant colour.

{ Psycasm | Continue reading }

photo { Adam Amengual }

colors, fights, ideas, psychology | October 1st, 2010 6:10 pm

New study finds groups demonstrate distinctive ‘collective intelligence’ when facing difficult tasks. (…)

That collective intelligence, the researchers believe, stems from how well the group works together. For instance, groups whose members had higher levels of “social sensitivity” were more collectively intelligent. “Social sensitivity has to do with how well group members perceive each other’s emotions,” says Christopher Chabris. (…)

The average and maximum intelligence of individual group members did not significantly predict the performance of their groups overall. (…)

Only when analyzing the data did the co-authors suspect that the number of women in a group had significant predictive power. “We didn’t design this study to focus on the gender effect,” Malone says. “That was a surprise to us.” However, further analysis revealed that the effect seemed to be explained by the higher social sensitivity exhibited by females, on average.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

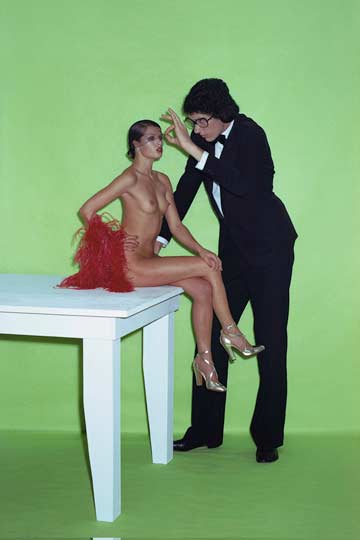

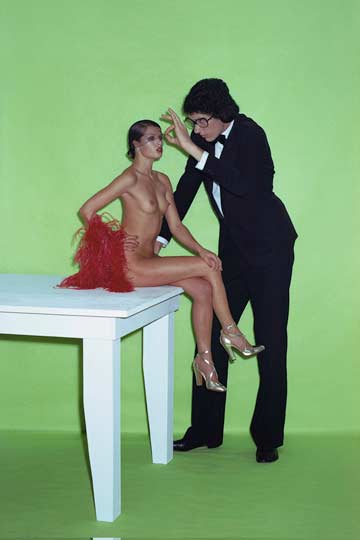

photo { Helmut Newton }

ideas, psychology, relationships | October 1st, 2010 5:45 pm

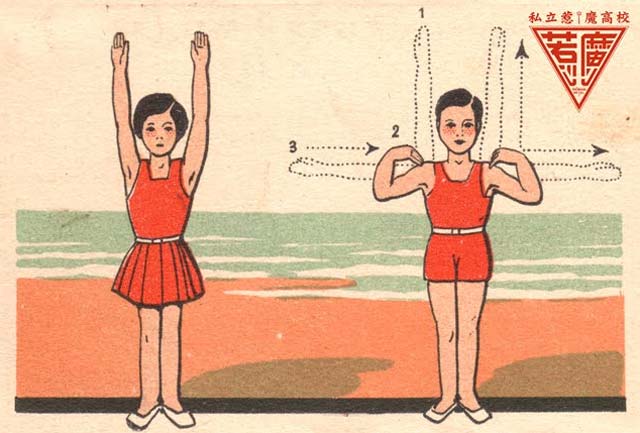

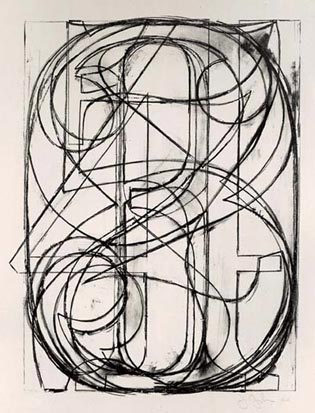

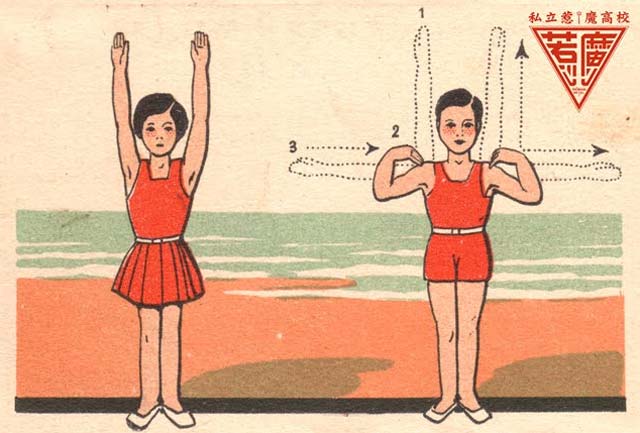

Singapore math is taking hold in schools throughout the country. Here in New York City, home to the nation’s largest school system, a small but growing number of schools have adopted this approach, based on Singapore’s national math system.

Many teachers and parents here say Singapore math helps children develop a deeper understanding of numbers and math concepts than they gain through other math programs.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

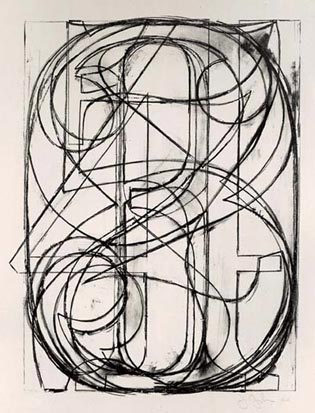

artwork { Jasper Johns, 0 through 9, 1960 }

asia, kids, mathematics, new york | October 1st, 2010 4:10 pm

Psychologists tend to take the experience of regret as a given, and occupy themselves with the study of its antecedents, consequences, and boundary conditions. They find, for example, that short-term regret is focused on things we did rather than did not do, whereas long-term regret shows the reverse pattern. (…)

Regret springs from the wish to undo an earlier decision. Why? Typically, we feel regret when-and because-we have obtained new information.

{ Psychology Today | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | September 29th, 2010 8:35 am

We are used to thinking of culture as a social factor and not a biological factor. We attribute dispositions such as being individualistic or being collectivist to the country that one was brought up in, but no one has really looked into why certain cultures tend to be that way. An emerging field of research called cultural neuroscience says that cultural values can be shaped by the brain and genes.

For example, in one striking example I read about quite recently, one hypothesis put forth for the reason why Asian people like spicy food was because spices conferred natural bacteria killing properties that was especially important in a humid climate where food went bad. Over time, the hypothesis goes, people who liked spicy food more and ate more spicy food were less prone to stomach diseases that killed the others, thus passing on their genes for the next generation. A similar finding was found when examining lactose intolerance. Lactose intolerance is far more prevalent in certain regions of Asia where the rearing of lifestock for milk is less common. In Europe however, up to 95% are able to digest lactose, and this is reflected in their preference for milk products like cream and cheese.

{ Psychothalamus | Continue reading }

related { Chillies burn our tongues, make our eyes water and bring us out in a sweat. A developmental psychologist looks at a peculiarly human form of masochism | The Guardian | full story }

photo { Molly Schiot }

food, drinks, restaurants, science | September 29th, 2010 8:13 am

Some people are surprised, even disturbed, by the idea that our vision does not give us an accurate picture of what we look at. For example, the colours we experience are not a measure of the wavelength of the light entering our eyes. But accuracy is not the point of vision; the function is to be useful and colour consistency is far more useful then fidelity to wavelength spectra. The same surprise is shown in the reaction to the idea that our memories are reworked continuously so that over time they lose their accuracy. (…)

A great deal of biological energy is used to create memories and to re-consolidate them and therefore we can assume that they have a very important biological role. (…)

We first have to have the experiences to remember – we create consciousness experiences which become stored as temporary memories. These are soon made more permanent as an event or an episode. Over weeks, months, years, decades they are continually reworked and re-consolidated. They are packaged together and lose their individuality, they are up-dated by newer memories, they are categorized and lose detail not related to their category. Eventually they lose their character as episodic memory and became more a factual or semantic type of memory.

{ Janet Kwasniak | Continue reading }

psychology, science, time | September 27th, 2010 9:28 pm

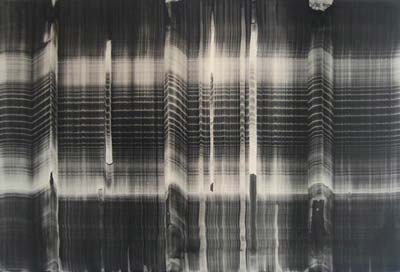

In a recent fMRI study, researchers showed that Cantonese verbs and nouns are processed in (slightly) different parts of the brain than English nouns and verbs in bilinguals. (…)

Chinese nouns and verbs showed a largely overlapping pattern of cortical activity. In contrast, English verbs activated more brain regions compared to English nouns. Specifically, the processing of English verbs evoked stronger activities of left putamen, left fusiform gyrus, cerebellum, right cuneus, right middle occipital areas, and supplementary motor area. The cognition of English nouns did not evoke stronger activities in any cortical regions.

This is truly language affecting thought, no? The point of general interest to linguist is that bilingual speakers seem to process words in their two languages differently. Cantonese words are processed using diffuse brain regions and English words are processed using localized regions (this is a simplified explanation of course).

{ The Lousy Linguist | Continue reading }

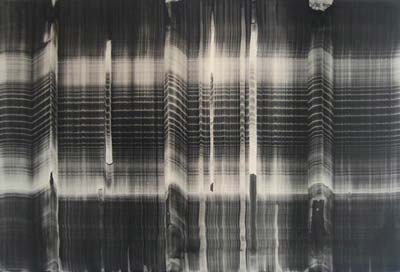

painting { Miriam Cabessa, Little Black 2, 2008 | oil on linen }

Linguistics, brain | September 27th, 2010 8:54 pm

Consider the orange. Citrus sinensis. Its fleshy, segmented fruit has a tight-fitting skin and contains at least 300 different chemicals. It is not easy to grow. It takes about 13 gallons of water. The fruit only ripens on the tree before it’s picked. And since they’re only grown in six states, oranges are either packed and shipped to places where citrus doesn’t grow or processed into one of America’s favorite breakfast drinks: orange juice. (…)

Lahousse charted the 10 key components of an orange in a sunburst diagram. Each color stands for a key flavor component and using the right combination of other ingredients, one could create the taste of an orange without actually using an orange.

{ Good magazine | Continue reading }

artwork { Mark Rothko, Orange and Yellow, 1956 }

Botany, food, drinks, restaurants, science | September 27th, 2010 5:39 pm

Babies can readily differentiate pet dogs and cats from “life-like” battery-operated toy dogs and cats. Babies will smile at, hold, follow, and make sounds in response to the live animals more than in response to the toys. In one study, 9 month olds were more interested in a live rabbit than an adult female stranger or a wooden turtle. A 1989 study of 2- to 6-year-olds with animals in their classrooms showed that children ignored realistic stuffed animals (80% never looked at them), but that live animals - especially dogs and birds - captured the attention of the children. Seventy-four percent touched the dog, 21% kissed the dog, and more than 66% talked to the bird.

Living with pets seems to stimulate children’s learning about basic biology. In one study, Japanese researchers showed that kindergarteners who had cared for pet goldfish better understood unobservable biological traits of their goldfish, and gave more accurate answers to questions like “does a goldfish have a heart?” (…)

When asked to name the 10 most important individuals in their lives, 7- and 10-year-olds on average included 2 pets.

{ Thoughtful Animal/ScienceBlogs | Continue reading }

animals, kids, psychology, relationships | September 27th, 2010 3:17 pm

Now, medical professionals have known for a very long time that the vagina is an ideal route for drug delivery. The reason for this is that the vagina is surrounded by an impressive vascular network. Arteries, blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels abound, and—unlike some other routes of drug administration—chemicals that are absorbed through the vaginal walls have an almost direct line to the body’s peripheral circulation system. So it makes infinite sense, argue Gallup and Burch, that like any artificially-derived chemical substance inserted into the vagina via medical pessary, semen might also have certain chemical properties that tweak female biology. (…)

semen has a very complicated chemical profile, containing over 50 different compounds (including hormones, neurotransmitters, endorphins and immunosupressants) each with a special function and occurring in different concentrations within the seminal plasma. Perhaps the most striking of these compounds is the bundle of mood-enhancing chemicals in semen. There is good in this goo. Such anxiolytic chemicals include, but are by no means limited to, cortisol (known to increase affection), estrone (which elevates mood), prolactin (a natural antidepressant), oxytocin (also elevates mood), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (another antidepressant), melatonin (a sleep-inducing agent) and even serotonin (perhaps the most well-known antidepressant neurotransmitter).

Given these ingredients—and this is just a small sample of the mind-altering “drugs” found in human semen—Gallup and Burch, along with psychologist Steven Platek, now at the University of Liverpool, hypothesized that women having unprotected sex should be less depressed than suitable control participants.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

illustration { Sen Hesse }

science, sex-oriented | September 27th, 2010 3:00 pm

It is a cliché that the brain is the “largest sex organ,” but the repetition of the phrase doesn’t make it any less true. The mechanics of its role during sex are less obvious and less well understood than that of the body’s other sex organs, but by using brain imaging scans, neuroscientists have begun to get a sense of what parts of the brain light up during sex, especially at the moment of orgasm. (…)

One early study of orgasms suggests that the subjective experience of orgasm is very similar between men and women. Despite having different anatomies, men and women seem to be hard-wired to experience sexual pleasure in the same way. But does this translate to a similarity in the brain? (…)

Much more so than men’s brains, female brains go mysteriously silent during orgasm. In particular, the left lateral orbitofronal cortex and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, areas involved in self-control and social judgment, respectively, are deactivated. Brain activity also fell in the amygdala, suggesting a similar, albeit more drastic, drop in vigilance and emotion as in men. “At the moment of orgasm, women do not have any emotional feelings,” Holstege was quoted as saying.

{ Big Think | Continue reading }

painting { Mark Sheinkman, Lourel, 2010 | oil, alkyd and graphite on linen }

brain, relationships, science, sex-oriented | September 24th, 2010 1:06 pm

Where are you right now? Maybe you are at home, the office or a coffee shop—but such responses provide only a partial answer to the question at hand. Asked another way, what is the location of your “self” as you read this sentence? Like most people, you probably have a strong sense that your conscious self is housed within your physical body, regardless of your surroundings.

But sometimes this spatial self-location goes awry. During a so-called out-of-body experience, for example, one’s self seems to be transported outside the physical body into a surreal perspective—some people even believe they are viewing their bodies from above, as though their true selves were floating. In a related experience, people with a delusion known as somatoparaphrenia disown one of their limbs or confuse another person’s limb for their own. Such warped perceptions help researchers understand the neuroscience of selfhood.

A new paper offers examples of rare bodily illusions that are not confined to a single limb, nor are they complete out-of-body experiences—they are somewhere in between. These illusory body perceptions, described in the September issue of Consciousness and Cognition, could offer novel clues about how the brain maintains a link between the physical and conscious selves, or what the researchers call “bodily self-consciousness.”

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

photo { Imp Kerr & Associates, NYC }

brain, science | September 23rd, 2010 11:04 am

We make a mistake when we think of cancer as a noun. It is not something you have, it is something you do. Your body is probably cancering all the time. What keeps it under control is a conversation that is happening between your cells, and the language of that conversation is proteins. Proteomics will allow us to listen in on that conversation, and that will lead to much better way to treat cancer.

{ Edge | Continue reading }

health, science | September 23rd, 2010 10:46 am

I’m sure most of you have heard of the twin paradox “in which a twin makes a journey into space in a high-speed rocket and returns home to find he has aged less than his identical twin who stayed on Earth.” This paradox has been worked out for special relativity in Minkowski spacetime. Recently, Boblest et al. worked out the details using general relativity for an expanding universe. (…)

The twins in the paper have names: Eric and Tina. Eric stays on Earth while Tina accelerates away from Earth with constant acceleration α = 9.8 m/s2 until her clock shows 5 years have past. Then she decelerates by the same magnitude coming to a complete stop after ten years then begins her journey back to earth accelerating then decelerating in the same 5 year intervals. Finally, after 20 years has transpired on her clock she has returned to earth being now 20 years old. (…) Eric is nearly 350 years old when Tina returns.

{ The Eternal Universe | Continue reading }

space, time | September 23rd, 2010 10:40 am

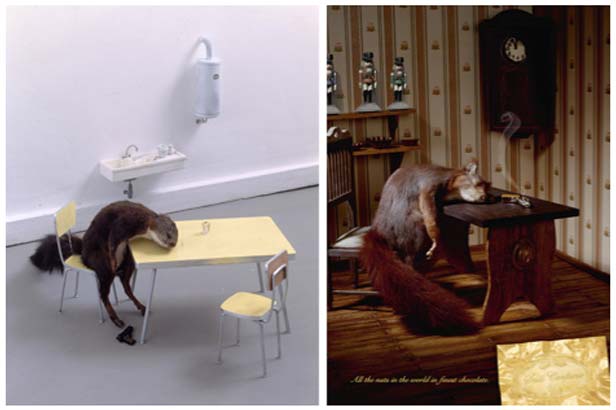

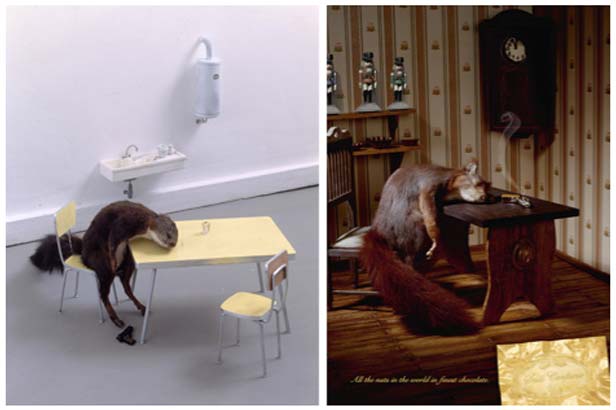

By what age do children recognise that plagiarism is wrong?

To view plagiarism as an adult does, a child must combine several pieces of a puzzle: they need to understand that not everyone has access to all ideas; that people can create their own ideas; and that stealing an idea, like stealing physical property, is wrong.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

images { Left: Maurizio Cattelan, Bidibidobidiboo, 1996 | Right: Print ad for Seidl Confiserie, 2008. Advertising Agency: Serviceplan München/Hamburg, Germany. Maurizio Cattelan was not credited. }

ideas, kids, psychology | September 23rd, 2010 10:35 am

Most of us know, but often forget, that handwriting is not natural. We are not born to do it. There is no genetic basis for writing. Writing is not like seeing or talking, which are innate. Writing must be taught.

About 6,000 years ago, the Sumerians created the first schools, called tablet houses, to teach writing. They trained children in Sumerian cuneiform by having them copy the symbols on one half of a soft clay tablet onto the other half, using a stylus. When children did this — and when the Sumerians invented a system of representation, a way to make one thing symbolize another — their brains changed.

Maryanne Wolf explains the neurological developments writing wrought: “The brain became a beehive of activity. A network of processes went to work: The visual and visual association areas responded to visual patterns (or representations); frontal, temporal, and parietal areas provided information about the smallest sounds in words …; and finally areas in the temporal and parietal lobes processed meaning, function and connections.”

The Sumerians did not have an alphabet — nor did the Egyptians, who may have gotten to writing earlier. Which alphabet came first is debated; many consider it to be the Greek version, a system based upon Phoenician. Alphabets created even more neural pathways, allowing us to think in new ways (neither better nor worse than non-alphabetic systems, like Chinese, yet different nonetheless).

{ Miller-McCune | Continue reading }

brain, flashback | September 22nd, 2010 2:32 pm

Photographs can serve as valuable memory aids but can also contribute to memory inaccuracies. The present studies examine whether photographs can make people claim they performed an action that they did not in fact perform. (…) Findings suggest that photographs can mislead people as to what they did or did not do.

{ Applied Cognitive Psychology /Wiley | Continue reading }

photo { Robb Johnson }

photogs, psychology | September 21st, 2010 4:29 pm

Beyond the practical experiences and impressions being held for ages from ancient times, the scientific observations and surveys indicate that psychopathological symptoms, especially those belonging to the bipolar mood disorder (bipolar I and II), major depression and cyclothymia categories occur more frequently among writers, poets, visual artists and composers, compared to the rates in the general population. Self-reports of writers and artists describe symptoms in their intensively creative periods which are reminiscent and characteristic of hypomanic states. Further, cognitive styles of hypomania (e.g. overinclusive thinking, richness of associations) and originality-prone creativity share many common as indicated by several authors.

Among the eminent artists showing most probably manic-depressive or cyclothymic symptoms were: E. Dickinson, E. Hemingway, N. Gogol, A. Strindberg, V. Woolf, Lord Byron (G. Gordon), J. W. Goethe, V. van Gogh, F. Goya, G. Donizetti, G. F. Händel, O. Klemperer, G. Mahler, R. Schumann, and H. Wolf. Based on biographies and other studies, brief descriptions are given in the present article on the personality character of Gogol; Strindberg, Van Gogh, Händel, Klemperer, Mahler, and Schumann.

Further example is the enigmatic silence and withdrawal from opera composing of Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868), which is still a matter of various theories and explanations. Until his life of 37 years he composed 39 operas and lived almost another 40 years without composing any new one. Biographies show that severe depressive sufferings played a role in that withdrawal and silence, while in his juvenile years most probably hypomanic personality traits contributed to the extreme achievements and very fast composing techniques. Analysing the available biographies of Rossini and the character of music he composed (e.g. opera buffa, Rossini crescendo) strongly suggests the medical diagnosis of a bipolar affective illness.

Comparing to the general population, bipolar mood disorder is highly overrepresented among writers and artists. The cognitive and other psychological features of artistic creativity resemble many aspects of the hypomanic symptomatology. It may be concluded that bipolar mood traits might contribute to highly creative achievements in the field of art. At the same time, considering the risks, the need of an increased medical care is required.

{ Orv Hetil, 2004/PubMed }

ideas, music, poetry, psychology, weirdos | September 21st, 2010 3:50 pm

We understand the dynamics of the world around us as by associating pairs of events, where one event has some influence on the other. These pairs of events can be aggregated into a web of memories representing our understanding of an episode of history. The events and the associations between them need not be directly experienced—they can also be acquired by communication.

When we think and talk about changes in the world around us, we weave together discrete episodes to create a narrative. Events along the timeline of this narrative are connected by associations. For instance, if we recall that “since the gas price went up, I decided to buy a fuel-efficient car”, we can represent “gas price going up” and “I buying a fuel-efficient car” as two nodes of a directed graph with an associative arc connecting the former to the latter. Such arcs need not be a first-hand experience; we might believe that “increased political tension in the middle-East drove the gas price up” drawing an arc from “increased political tension in the middle-East” to “gas price going up”. Our recollection and understanding of the past can thus be represented as a web of events connected by associations like the above example.

Such autobiographical narratives take place within a social context. They are fluid and dynamic, bearing the hallmark of the social context within which they emerge. Associations between events are not only dependent on the personal experiences of the individual, but also on social processes of construction and re-construction that ultimately give place to what we experience as a collective history. Much of the social processes of collective history occur in conversational and communicative contexts, which convey personal and social meaning to events. Communication reinforces the memories of interacting individuals, and it is through this process that associative arcs can spread in a population so that memory webs come to share common elements across people. From this process, associative arcs can spread in a population so that groups of people share part of their webs of memories. We call such subnetworks in common to many people collective memories.

In this paper, we will investigate a model of how the web of memories of a population evolves, including the mechanisms mentioned above. We use the model to investigate the stability of collective memories, the minimal requirements for cycles (sequences of associations that must violate the time-ordering of the events) and the possibility that communication can lead to the formation of groups sharing collective memories. There are other conceivable mechanisms than communication for the evolution of a person’s web of memories: first-hand experiences, mass-medial information and logical deduction (to fill out gaps in one’s web of memories). In our model of the dynamics of collective memories these other mechanisms are grouped together and, as opposed to communication, treated as external input to the model.

Communications as a process for the understanding of history—the formation of causal networks, both on an individual and aggregate level—has been studied in the qualitative tradition of social and behavioral sciences. One has investigated the processes behind collective memories—how groups of people maintain a common narrative of a period of history. This type of research are to a large extent case studies about, ethnic groups’ memories of traumatic events, like the Jews’ collective memories of the holocaust, or comparative studies like the Palestinians and Israelis different histories of the state of Israel.

Recently there has been a considerable interest in models of the spreading of information and opinions between people. Such studies have for example investigated the minimal requirements for fads to spread, for groups of people to make correct collective decisions or predictions, and the conditions for a diversity of opinions (as opposed to a widespread consensus) to be the result of communication. In the present work we follow this tradition and create a model of collective memory emerging from communication. This model will take a web of memories as input. In this study we take this input network from an empirical dataset. The paper starts discussing the structure of this empirical data, then proceeds to the construction of the model and finally discusses the results of the simulations.

{ PLoS One | Continue reading }

collage { Lola Dupré }

psychology, science | September 21st, 2010 3:36 pm