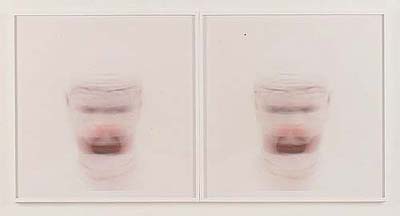

Art’s link with money is not new, though it does continue to generate surprises. On Friday night, Christie’s in London plans to auction another of Damien Hirst’s medicine cabinets: literally a small, sliding-glass medicine cabinet containing a few dozen bottles or tubes of standard pharmaceuticals: nasal spray, penicillin tablets, vitamins and so forth. This work is not as grand as a Hirst shark, floating eerily in a giant vat of formaldehyde, one of which sold for more than $12 million a few years ago. Still, the estimate of up to $239,000 for the medicine cabinet is impressive — rather more impressive than the work itself.

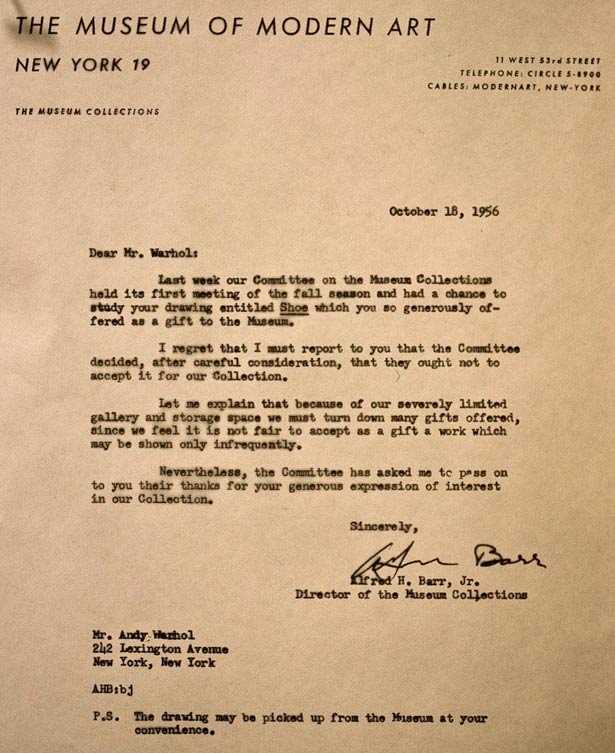

No disputing tastes, of course, if yours lean toward the aesthetic contemplation of an orderly medicine cabinet. Buy it, and you acquire a work of art by the world’s richest and — by that criterion — most successful living artist. Still, neither this piece nor Mr. Hirst’s dissected calves and embalmed horses are quite “by” the artist in a conventional sense. Mr. Hirst’s name rightfully goes on them because they were his conceptions. However, he did not reproduce any of the medicine bottles or boxes in his cabinet (in the way that Warhol actually recreated Brillo boxes), nor did he catch a shark or do the taxidermy.

In this respect, the pricey medicine cabinet belongs to a tradition of conceptual art: works we admire not for skillful hands-on execution by the artist, but for the artist’s creative concept. (…)

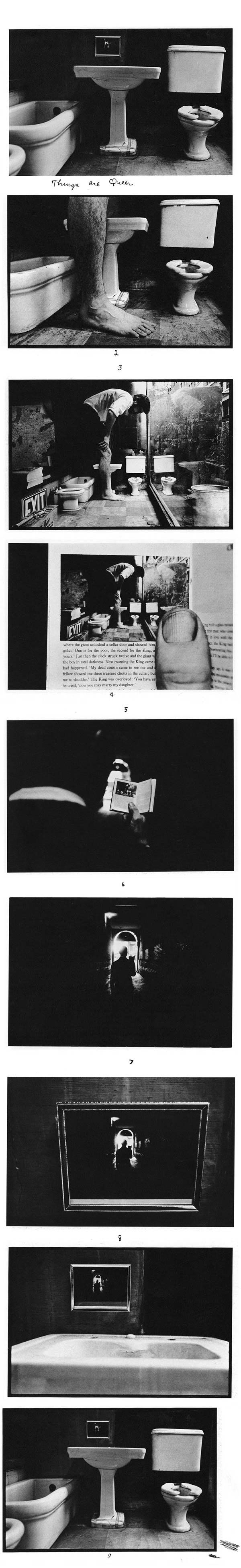

Since the endearingly witty Marcel Duchamp invented conceptual art 90 years ago by offering his “ready-mades” — a urinal or a snow shovel, for instance — for gallery shows, the genre has degenerated. Duchamp, an authentic artistic genius, was in 1917 making sport of the art establishment and its stuffy values. By the time we get to 2009, Mr. Hirst and Mr. Koons are the establishment.

Does this mean that conceptual art is here to stay? That is not at all certain, and it is not just auction results that are relevant to the issue. To see why works of conceptual art have an inherent investment risk, we must look back at the whole history of art. (…)

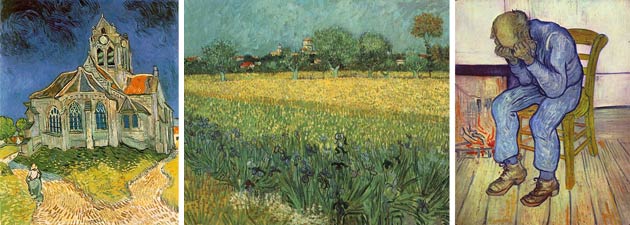

The appreciation of contemporary conceptual art, on the other hand, depends not on immediately recognizable skill, but on how the work is situated in today’s intellectual zeitgeist. That’s why looking through the history of conceptual art after Duchamp reminds me of paging through old New Yorker cartoons. Jokes about Cadillac tailfins and early fax machines were once amusing, and the same can be said of conceptual works like Piero Manzoni’s 1962 declaration that Earth was his art work, Joseph Kosuth’s 1965 “One and Three Chairs” (a chair, a photo of the chair and a definition of “chair”) or Mr. Hirst’s medicine cabinets. Future generations, no longer engaged by our art “concepts” and unable to divine any special skill or emotional expression in the work, may lose interest in it as a medium for financial speculation and relegate it to the realm of historical curiosity.

In this respect, I can’t help regarding medicine cabinets, vacuum cleaners and dead sharks as reckless investments. Somewhere out there in collectorland is the unlucky guy who will be the last one holding the vacuum cleaner, and wondering why.

{ Denis Dutton/NY Times | Continue reading }

The best explanation of the art market may be that it is inexplicable, which is one reason its alchemy continues to fascinate and capture headlines. In no other market do we lavish wealth on such useless and arbitrary things. Advanced systems of trade that are usually the facilitators of market intelligence—international public auctions and historical price indexes—only offer a false sense of comprehension while further distorting art’s valuation.

Yet if such things could be measured in degrees, the art market of today seems more unexplainable than ever. The prices paid for certain types of post-war and contemporary art continues to outpace prices for older work as well as recent art of greater nuance. Tens of millions of dollars may still chase after art of dubious formal qualities—factory-made work by Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, smears by Francis Bacon and silkscreens by Warhol.

Big money’s relationship to “cheap” contemporary art is a recent phenomenon. It began in the 1960s, as Pop Art commercialized the avant-garde—not just selling the avant-garde, but also involving commercialism in defining the avant-garde. Whereas many Abstract Expressionists died before striking it rich, several of the avant-garde artists who came of age in the 1960s experienced a more profitable fate. (…)

In 2006, Tobias Meyer infamously remarked that “the best art is the most expensive because the market is so smart.” The quote received wide circulation because of its patent absurdity. A market is only as smart as the people who control it, and the art market has proved to be a dull creature when it comes to appreciating a broad range of artistic qualities. But to give Meyer credit, the market can be very smart about the art that speaks to it.

The art market has a unique talent for promoting art about the market. Since exhibition history enhances value, the collectors of what we might call “market art” have a vested interest in seeing their work take up space in traditional public collections. They often have the financial leverage to make it happen. In this way, the hedge-fund collector Steven A. Cohen could place Damien Hirst’s shark tank on temporary loan at the Metropolitan Museum. The oversized trinkets of Jeff Koons start appearing at the same time in the museum’s rooftop gallery.

{ The New Criterion | Continue reading }