ideas

The dialects of Madagascar belong to the Greater Barito East group of the Austronesian family and it is widely accepted that the Island was colonized by Indonesian sailors after a maritime trek which probably took place around 650 CE. The language most closely related to Malagasy dialects is Maanyan but also Malay is strongly related especially for what concerns navigation terms. Since the Maanyan Dayaks live along the Barito river in Kalimantan (Borneo) and they do not possess the necessary skill for long maritime navigation, probably they were brought as subordinates by Malay sailors.

In a recent paper we compared 23 different Malagasy dialects in order to determine the time and the landing area of the first colonization. In this research we use new data and new methods to confirm that the landing took place on the south-east coast of the Island. Furthermore, we are able to state here that it is unlikely that there were multiple settlements and, therefore, colonization consisted in a single founding event.

{ Maurizio Serva, The settlement of Madagascar: what dialects and languages can tell | Continue reading }

Africa, Linguistics, flashback | August 1st, 2011 4:30 pm

A lot of occupations that didn’t exist years ago: two college graduate daughters, one a web designer for a financial firm, other works with a company that does social media marketing. Didn’t exist when they were born. Proliferation of new occupations.

Harder to be a Renaissance person. It was imaginable 400 years ago that you could read, master a relatively large part of the world’s knowledge. Seen it argued that Leibniz knew just about everything that could be known at that time. Da Vinci superior in many fields. Now a Renaissance person if you are good in a couple of things, if you know something about a lot of things. The cost of mastering a lot of things has gone up. (…) How much could a Newton or Leibniz today master? Not all of it. When we went to graduate school in economics (…) Finance was around, but behavioral economics and experimental economics were not, or were less prominent. I used to call myself a macroeconomist–I can’t follow macroeconomics; sort of can; highly mathematical, Euler equation stuff. (…) Profusion of journals in every discipline. If you want to call yourself a master of any field, not sure that leads to true mastery. (…)

Knowledge is more dispersed. Not just an issue for people trying to become academics. True for somebody in business: if you want to be a CEO, there are many more things you have to understand than you used to. You didn’t have to understand information technology to be a CEO. Didn’t have to be an expert in global supply chain management. Didn’t necessarily have to understand logistics, be as sophisticated in finance.

Even for consumers, amount of knowledge you need is more. More different financial instruments available for you to either trip up on or take advantage of. All sorts of different products and services that didn’t exist. (…) Households are outsourcing more of the food preparation, cleaning, lawn care, more complex forms of electronic communication–have cell phone, do you still keep your land line? Life more complex for everybody. Weird thing. Have computer network in house, access Internet wirelessly; running an IT center. Measurement question: has my house gotten more specialized or less specialized? What am I doing with an IT network in my house? Verizon supplies it; I don’t master much of it other than opening the door to let someone in to drill in my wall. Hard to measure these phenomena. Makes us very much dependent on other people’s expertise.

{ Arnold Kling/EconTalk | Continue reading }

economics, ideas | July 27th, 2011 8:40 pm

Scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have found that when just 10 percent of the population holds an unshakable belief, their belief will always be adopted by the majority of the society. The scientists, who are members of the Social Cognitive Networks Academic Research Center (SCNARC) at Rensselaer, used computational and analytical methods to discover the tipping point where a minority belief becomes the majority opinion. (…)

The percentage of committed opinion holders required to influence a society remains at approximately 10 percent, regardless of how or where that opinion starts and spreads in the society.

{ ScienceBlog | Continue reading }

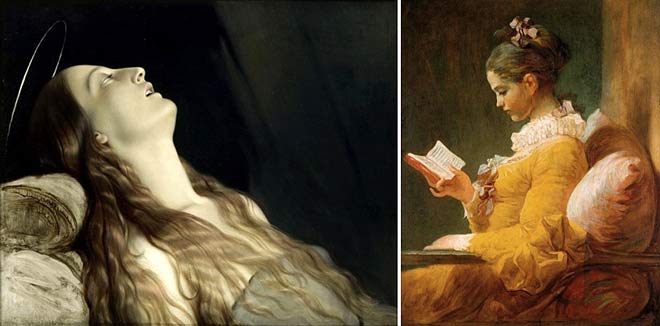

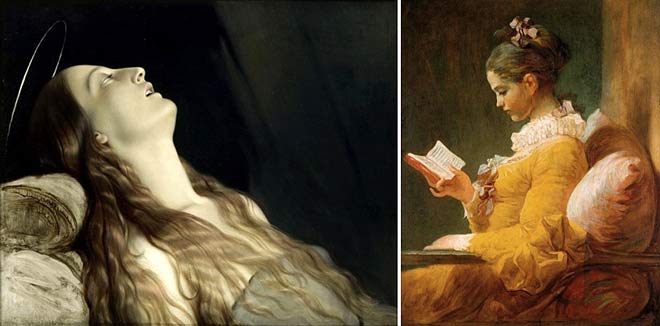

paintings { 1. Hippolyte Delaroche, Louise Vernet, Wife of the Artist, on Her Deathbed, 1845 | 2. Fragonard, The Reader, ca.1770-72 }

ideas, psychology | July 27th, 2011 6:06 pm

science, time | July 27th, 2011 6:01 pm

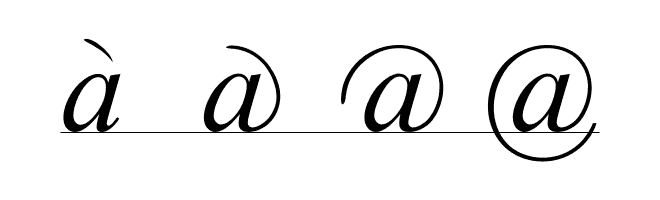

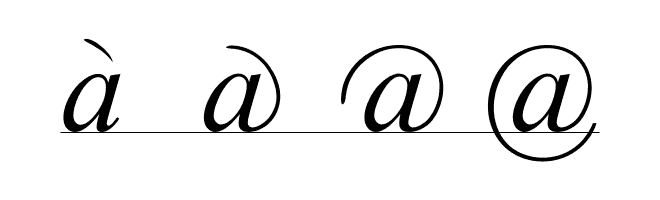

Like the ampersand, the ‘@’ symbol is not strictly a mark of punctuation; rather, it is a logogram or grammalogue, a shorthand for the word ‘at’. Even so, it is as much a staple of modern communication as the semicolon or exclamation mark, punctuating email addresses and announcing Twitter usernames. Unlike the ampersand, though, whose journey to the top took two millennia of steady perseverance, the at symbol’s current fame is quite accidental. It can, in fact, be traced to the single stroke of a key made almost exactly four decades ago.

In 1971, Ray Tomlinson was a 29-year-old computer engineer working for the consulting firm Bolt, Beranek and Newman. Founded just over two decades previously, BBN had recently been awarded a contract by the US government’s Advanced Research Projects Agency to undertake an ambitious project to connect computers all over America. The so-called ‘ARPANET’ would go on to provide the foundations for the modern internet, and quite apart from his technical contributions to it, Tomlinson would also inadvertently grant it its first global emblem in the form of the ‘@’ symbol.

{ Shady Characters | Continue reading }

related { There are several theories about the origin of @ | Merchant@florence wrote it first 500 years ago }

Linguistics, flashback, technology | July 26th, 2011 11:00 am

Illegal markets differ from legal markets in many respects. Although illegal markets have economic significance and are of theoretical importance, they have been largely ignored by economic sociology. In this article we propose a categorization for illegal markets and highlight reasons why certain markets are outlawed. We perform a comprehensive review of the literature to characterize illegal markets along the three coordination problems of value creation, competition, and cooperation. The article concludes by appealing to economic sociology to strengthen research on illegal markets and by suggesting areas for future empirical research. (…)

Markets are arenas of regular voluntary exchange of goods or services for money under conditions of competition (Aspers/Beckert 2008). The exchange of goods or services does not constitute a market when the exchange takes place only very irregularly and when there is no competition either on the demand side or on the supply side. Markets are illegal when either the product itself, the exchange of it, or the way in which it is produced or sold violates legal stipulations. What makes a market illegal is therefore entirely dependent on a legal definition.

When a market is defined as illegal, the state declines the protection of property rights, does not define and enforce standards for product quality, and can prosecute the actors within it. Not every criminal economic activity constitutes an illegal market; the product or service demanded may be too specific for competition to emerge, or it may simply be business fraud. Since illegality is defined by law, what constitutes an illegal market differs between legal jurisdictions and over time.

{ Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies | Continue reading | PDF }

Linguistics, economics, law | July 25th, 2011 9:07 am

Philosophy, like all other studies, aims primarily at knowledge. (…)

If you ask a mathematician, a mineralogist, a historian, or any other man of learning, what definite body of truths has been ascertained by his science, his answer will last as long as you are willing to listen. But if you put the same question to a philosopher, he will, if he is candid, have to confess that his study has not achieved positive results such as have been achieved by other sciences. (…)

The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty. The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. As soon as we begin to philosophize, on the contrary, we find that even the most everyday things lead to problems to which only very incomplete answers can be given.

{ Bertrand Russel, The Value of Philosophy, 1912 | Continue reading }

photo { Richard Avedon }

ideas | July 22nd, 2011 8:46 pm

If you ask doctors what is the worst part of their jobs, what do you think they say? Carrying out difficult, painful procedures? Telling people they’ve only got months to live? No, it’s something that might seem much less stressful: administration.

We tend to downplay day-to-day irritations, thinking we’ve got bigger fish to fry. But actually people’s job satisfaction is surprisingly sensitive to daily hassles. It might not seem like much but when it happens almost every day and it’s beyond our control, it hits job satisfaction hard.

{ 10 Psychological Keys to Job Satisfaction | PsyBlog | Continue reading }

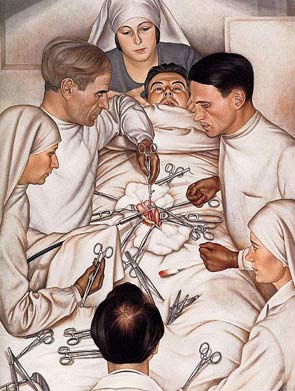

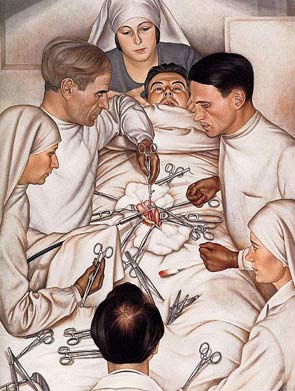

artwork { Christian Schad, Operation, 1929 }

guide, ideas | July 22nd, 2011 7:00 pm

For someone who remembers the old days, the food is the most startling thing about modern England. English food used to be deservedly famous for its awfulness–greasy fish and chips, gelatinous pork pies, and dishwater coffee. Now it is not only easy to do much better, but traditionally terrible English meals have even become hard to find. What happened?

Maybe the first question is how English cooking got to be so bad in the first place. A good guess is that the country’s early industrialization and urbanization was the culprit. Millions of people moved rapidly off the land and away from access to traditional ingredients. Worse, they did so at a time when the technology of urban food supply was still primitive: Victorian London already had well over a million people, but most of its food came in by horse-drawn barge. And so ordinary people, and even the middle classes, were forced into a cuisine based on canned goods (mushy peas), preserved meats (hence those pies), and root vegetables that didn’t need refrigeration (e.g. potatoes, which explain the chips).

But why did the food stay so bad after refrigerated railroad cars and ships, frozen foods (better than canned, anyway), and eventually air-freight deliveries of fresh fish and vegetables had become available? Now we’re talking about economics–and about the limits of conventional economic theory. For the answer is surely that by the time it became possible for urban Britons to eat decently, they no longer knew the difference. The appreciation of good food is, quite literally, an acquired taste–but because your typical Englishman, circa, say, 1975, had never had a really good meal, he didn’t demand one.

{ Paul Krugman | Continue reading }

archives, food, drinks, restaurants, ideas | July 22nd, 2011 6:13 pm

Falsifiability or refutability is the logical possibility that an assertion can be contradicted by an observation or the outcome of a physical experiment. That something is “falsifiable” does not mean it is false; rather, that if it is false, then some observation or experiment will produce a reproducible result that is in conflict with it.

For example, the claim “atoms do exist” is unfalsifiable: Even if all observations made so far did not produce an atom, it is still possible that the next observation does. In the same way, “all men are mortal” is unfalsifiable: even if someone is observed who has not died so far, he could still die.

By contrast, “all men are immortal,” is falsifiable by the presentation of just one dead man. Not all statements that are falsifiable in principle are falsifiable in practice. For example, “it will be raining here in one million years” is theoretically falsifiable, but not practically so.

The concept was made popular by Karl Popper, who, in his philosophical criticism of the popular positivist view of the scientific method, concluded that a hypothesis, proposition, or theory talks about the observable only if it is falsifiable. Popper however stressed that unfalsifiable statements are still important in science, and are often implied by falsifiable theories. For example, while “all men are mortal” is unfalsifiable, it is a logical consequence of the falsifiable theory that “every man dies before he reaches the age of 150 years.”

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

Linguistics, ideas | July 22nd, 2011 4:20 pm

Traditionally, nostalgia has been conceptualized as a medical disease and a psychiatric disorder. Instead, we argue that nostalgia is a predominantly positive, self-relevant, and social emotion serving key psychological functions. Nostalgic narratives reflect more positive than negative affect, feature the self as the protagonist, and are embedded in a social context. Nostalgia is triggered by dysphoric states such as negative mood and loneliness. Finally, nostalgia generates positive affect, increases self-esteem, fosters social connectedness, and alleviates existential threat.

{ IngentaConnect }

ideas, psychology | July 20th, 2011 8:00 pm

Preface to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, written by J. M. D. Meiklejohn, the translator:

A previous translation of the Kritik exists, which, had it been satisfactory, would have dispensed with the present. But the translator had, evidently, no very extensive acquaintance with the German language, and still less with his subject. A translator ought to be an interpreting intellect between the author and the reader; but, in the present case, the only interpreting medium has been the dictionary.

Indeed, Kant’s fate in this country has been a very hard one. Misunderstood by the ablest philosophers of the time, illustrated, explained, or translated by the most incompetent,— it has been his lot to be either unappreciated, misapprehended, or entirely neglected.

{ via Jeremy Stangroom | Continue reading }

photo { Aaron Wojack }

ideas | July 20th, 2011 5:12 pm

Ron Jude: emmett is a book that brings form to a selection of my old, random photographs. (…) The heart of the project has to do with ideas about existence and the past. It’s structured to echo how we try to piece together coherent narratives through fragments of memory. (…)

Ed Panar: To me Same Difference is sort of an anti-project. I wanted to see what happened if you forgot about the rules, or never knew them in the first place. When you start noticing your own ‘rules’ or, habits of working, things start to become ambiguous pretty quickly. Why do we prefer doing things one way to another? What if we were to discover the basis for our strategies was arbitrary? If these pictures aren’t connected, can that be a point of connection? Photographs are so insanely open anyway. Even in the most constrained situations they will always be about more than the author was aware of in the moment.

{ Conversation between Ed Panar and Ron Jude | Ahorn |Continue reading }

photo { Ron Jude }

ideas, photogs | July 20th, 2011 4:52 pm

A few weeks ago, a woman asked me for advice about her teenage daughter. “She wants to be a writer,” the mother said. “What should we be doing?” (…)

First of all, let her be bored. Let her have long afternoons with absolutely nothing to do. (…)

Let her be lonely. Let her believe that no one in the world truly understands her. Give her the freedom to fall in love with the wrong person, to lose her heart, to have it smashed and abused and broken.

{ Molly Backes | Continue reading }

related { Weird Writing Habits of Famous Authors. }

photo { Thatcher Keats }

books, guide | July 19th, 2011 8:23 pm

More than a billion people cannot count on meeting their basic needs for food, sanitation, and clean water. Their children die from simple, preventable diseases. They lack a minimally decent quality of life.

At the same time, more than a billion people live at a hitherto unknown level of affluence. They think nothing of spending more to go out to dinner than the other billion have to live on for a month. Do they therefore have a high quality of life? Being able to meet one’s basic needs for food, water, and reasonable health is a necessary condition for having an adequate quality of life, but not a sufficient one.

In the past, we spent much of our day ensuring we would have enough to eat. Then we would relax and socialize. Now, for the affluent, it is so easy to meet our basic needs that we lack purpose in our daily activities—leading us to consume more, and thus to feel we do not earn enough for all that we “need.”

{ What does quality of life mean? And how should we measure it? Our panel of global experts weighs in. | World Policy Institute | Continue reading }

economics, ideas, within the world | July 19th, 2011 7:28 pm

Here is an obvious truth overlooked by too many: Almost all companies die. They have a theoretically infinite lifespan, but eventually, their day in the sun passes, their parts are sold off for scrap, they fade into the dim dusty pages of history. Sure, Europe has centuries old breweries and specialty foods companies, but they are notable because they are exceptions.

Think back to the original Dow Jones Industrials, filled as it was with Steam and Leather Belt companies, all gone bankrupt nearly a century ago. How many of the original companies in the DJIA are still even in existence?

Microsoft was once technology’s behemoth, the 800 pound gorilla, an unstoppable anti-competitive monopolist. And today? It was a great 20 year run, but it’s mostly over. They still have the cash horde and engineering chops to create a smash hit like the Kinect, and they are a cash cow, but the odds are, their glory days are behind them.

While some companies manage to have a second act — Apple and IBM are notable examples — they too, remain the exception.

Today, tech companies’ lifespans are measured in internet years. Any firms dominance of any given space is likely to cover a much smaller period — way less than a decade in real time. The obvious poster child for this syndrome? MySpace. Even mighty Google is seeing market share growth in search slip as competitors nip at its heels.

All of which leads me to the question of the day: Has Facebook missed its IPO window? (…)

There are signs that Google Plus is a worthy competitor: They quickly amassed 10 million users, and that is while they are in Beta.

{ Barry Ritholtz | Continue reading }

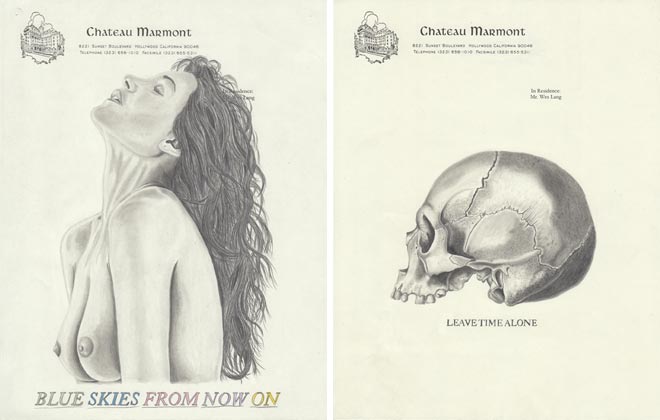

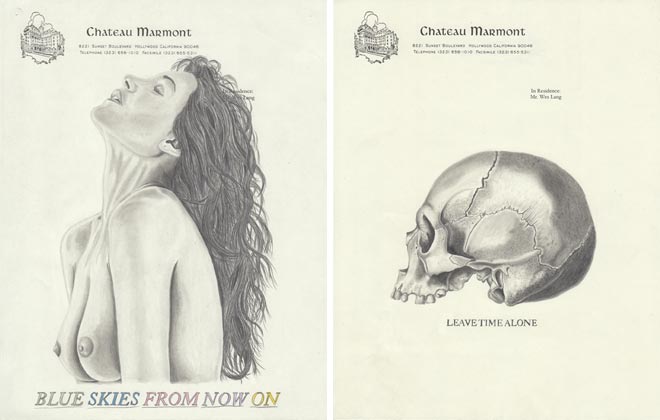

drawings { Wes Lang }

economics, ideas, technology | July 18th, 2011 2:40 pm

We don’t name babies to honor people any more. (…)

The 2008 election saw the historic election of America’s first black president. As you might expect, this event was commemorated in names. Approximately 60 more babies were named Barack or Obama than the year before. How big a deal was that? Well, it means hero naming for the new president accounted for .00001 percent of babies born, or one in every 71,000. Neither Barack nor Obama ranked among America’s top 2,000 names for boys. In other words, the effect was so trivially small that you would never notice it unless you went searching for it. Recent presidents with more familiar names, like Clinton, fared even worse on the name charts.

Now roll back the clock to the presidential election of 1896. Democrat William Jennings Bryan inspired a dramatic jump in the names Jennings and Bryan. Those jumps accounted for one in every 2,400 babies born — an effect 30 times bigger than Obama’s. It was enough to rank both names in the top 300 for the year. And in case your American history is a little shaky: Bryan lost the election.

{ The Baby Name Wizard | Continue reading }

photo { Mustafah Abdulaziz }

Onomastics, kids | July 18th, 2011 2:35 pm

Inferno (Italian for “Hell”) is the first part of Dante’s 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy. It is followed by Purgatorio and Paradiso. It is an allegory telling of the journey of Dante through what is largely the medieval concept of Hell.

Hell is depicted as nine circles of suffering located within the Earth.

First Circle: Limbo

Second Circle: Lust

Third Circle: Gluttony

Fourth Circle: Greed

Fifth Circle: Anger

Sixth Circle: Heresy

Seventh Circle: Violence

Eighth Circle: Fraud

Ninth Circle: Treachery

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

books, horror | July 18th, 2011 2:00 pm

Exaggeration means to make something seem larger, better, worse, etc than it really is. It is beyond limits of truth that creates doubt. It is a negative factor. So everybody is afraid of it. But nobody can avoid it. It causes irritation. It causes annoyance. Thus exaggerated remarks ultimately aggravate the target person. A fool or a wicked person exaggerates. A wise person neither fabricates the fact nor manufactures a new one. Similarly an innocent soul describes a fact unchanged and states it as it is.

Human nature is to exaggerate to gain something. This gain may either be classical or commercial or both simultaneously. Everybody tries to magnify his good traits and minimize his faults thus to win both ways. Emotion makes one blind. It kills clarity of thought. It escorts a lover in the kingdom of romance, far from the madding crowd. Emotion of the lover exaggerates the good traits of his fiancée hundred times and allures to love her. Later on when emotion is replaced by reality then faults of fiancée are exaggerated thousand times automatically and compel him to depart her mercilessly. Both of these events are striking examples of exaggeration and happen at the beckon of emotion. Exaggeration when is rendered for mere enjoyment, there lies no problem. At that jovial moment fact is fabricated and colored as per the sweet will of the narrators. Each of the narrators joins the competition of exaggeration. Since, they have no base and no brake at all, they stretch the truth with immense power of imagination. But it is too bad if this is used as a weapon to defame or harm to others.

Man beats his own drum with much intensity to gain name, fame and win the game. Due to exaggeration original story remains a mystery. As such they say, in history the names are real but the fact is either full of intentional exaggeration or suppression or both. So it is the topic of research to the scholars to find out the truth. Problem arises if a single topic is exaggerated differently by different scholars.

{ Dibakar Pal, Of Exaggeration, 2011 | SSRN | Continue reading }

ideas, shit talkers | July 15th, 2011 2:49 pm

The Misconception: When your beliefs are challenged with facts, you alter your opinions and incorporate the new information into your thinking.

The Truth: When your deepest convictions are challenged by contradictory evidence, your beliefs get stronger.

{ You are not so smart | Continue reading }

photo { Robert Frank }

ideas, psychology | July 15th, 2011 2:49 pm