science

If your doctor recommended a drug whose manufacturer’s consulting fees financed his summer home, would that give you pause? Would you trust a stockbroker who wanted to sell you on a risky mutual fund that gave him a commission for every sale? (…)

Within many fields, one solution has emerged: require people to disclose any ties that might sway their judgment. Such transparency, the rationale goes, encourages those in authority to behave more ethically.

But recent research by experimental psychologists is uncovering some uncomfortable truths: Disclosure doesn’t solve problems the way we think it does, and in fact it can actually backfire.

Coming clean about conflicts of interest, they find, can promote less ethical behavior by advisers. And though most of us assume we’d cast a skeptical eye on advice from a doctor, stockbroker, or politician with a personal stake in our decision, disclosure about conflicts may actually lead us to make worse choices.

{ Boston Globe | Continue reading }

psychology | May 16th, 2011 4:14 pm

An old technology is providing new insights into the human brain.

The technology is called electrocorticography, or ECoG, and it uses electrodes placed on the surface of the brain to detect electrical signals coming from the brain itself.

Doctors have been using ECoG since the 1950s (…) but in the past decade, scientists have shown that when connected to a computer running special software, ECoG also can be used to control robotic arms, study how the brain produces speech and even decode thoughts.

In one recent experiment, researchers were able to use ECoG to determine the word a person was imagining.

{ NPR | Continue reading }

brain, science | May 13th, 2011 6:22 pm

Adversity, we are told, heightens our senses, imprinting sights and sounds precisely in our memories. But new Weizmann Institute research, which appeared in Nature Neuroscience this week, suggests the exact opposite may be the case: Perceptions learned in an aversive context are not as sharp as those learned in other circumstances. (…)

“This likely made sense in our evolutionary past: If you’ve previously heard the sound of a lion attacking, your survival might depend on a similar noise sounding the same to you – and pushing the same emotional buttons. Your instincts, then, will tell you to run, rather than to consider whether that sound was indeed identical to the growl of the lion from the other day.”

{ Weizmann WW | Continue reading }

psychology | May 12th, 2011 6:59 pm

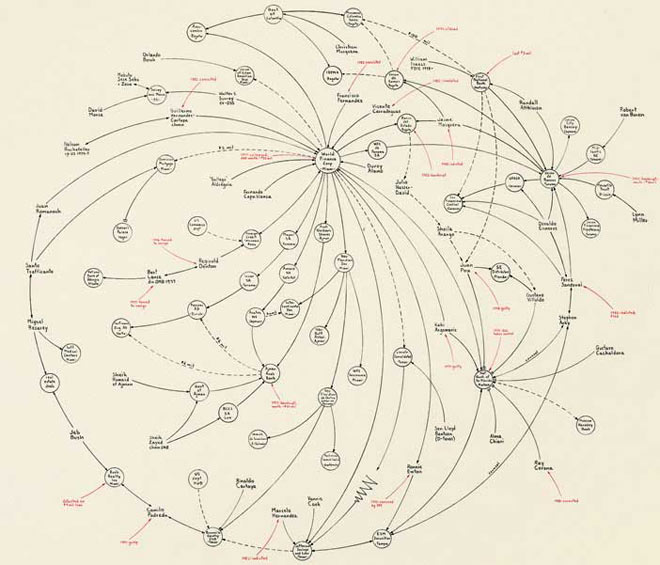

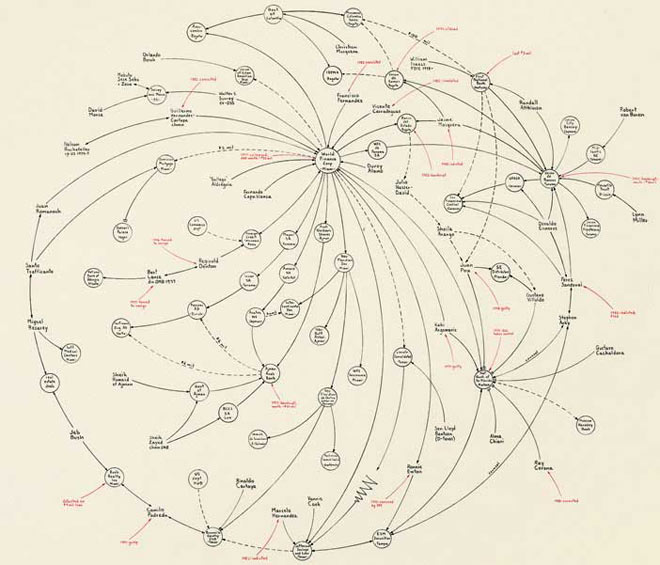

At first glance, a diagram of the complex network of genes that regulate cellular metabolism might seem hopelessly complex, and efforts to control such a system futile.

However, an MIT researcher has come up with a new computational model that can analyze any type of complex network — biological, social or electronic — and reveal the critical points that can be used to control the entire system.

Potential applications of this work, which appears as the cover story in the May 12 issue of Nature, include reprogramming adult cells and identifying new drug targets.

{ MIT News | Continue reading }

artwork { Mark Lombardi, World Finance Corporation and Associates, ca. 1970-84 }

ideas, science | May 12th, 2011 6:57 pm

The patterns of brain waves that occur during sleep can predict the likelihood that dreams will be successfully recalled upon waking up, according to a new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience. The research provides the first evidence of a ’signature’ pattern of brain activity associated with dream recall. It also provides further insight into the brain mechanisms underlying dreaming, and into the relationship between our dreams and our memories.

{ Neurophilosophy | Continue reading }

screenshot { Alfred Hitchcock, Psycho, 1960 | video }

related { 6 Easy Steps to Falling Asleep Fast }

brain, science | May 10th, 2011 7:23 pm

Compared with other mothers, women who deliver twins live longer, have more children than expected, bear babies at shorter intervals over a longer time, and are older at their last birth, according to a University of Utah study.

The findings do not mean having twins is healthy for women, but instead that healthier women have an increased chance of delivering twins, says demographer Ken. R. Smith, senior author of the study and a professor of family and consumer studies.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Manolo Campion }

health, kids, science | May 10th, 2011 7:09 pm

Barbers in the modern period are known to do mainly one thing: cut hair. For much of the last hundred and fifty years, their red and white striped barber poles signified their ability to produce a good clean shave and a quick trim. This was not always the case, however.

Up until the 19th century barbers were generally referred to as barber-surgeons, and they were called upon to perform a wide variety of tasks. They treated and extracted teeth, branded slaves, created ritual tattoos or scars, cut out gallstones and hangnails, set fractures, gave enemas, and lanced abscesses. (…)

During the 12th and 13th centuries, secular universities began to develop throughout Europe, and along with an increased study of medicine and anatomy came an increased study in surgery. This led to a split between academically trained surgeons and barber-surgeons, which was formalized in the 13th century. After this, academic surgeons signified their status by wearing long robes, and barber-surgeons by wearing short robes. Barber-surgeons were thus largely referred to as “surgeons of the short robe.”

{ Brain Blogger | Continue reading }

flashback, health, science | May 10th, 2011 7:05 pm

Could Einstein’s Theory of Relativity be a few mathematical equations away from being disproved? 12-year-old Jacob Barnett thinks so. And, he’s got the solutions to prove it.

Barnett, who has an IQ of 170, explained his expanded theory of relativity — in a YouTube video. (…)

While most of his mathematical genius goes over our heads, some professors at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey — the U.S. academic homeroom for the likes of Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and Kurt Gödel — have confirmed he’s on the right track to coming up with something completely new. (…)

“I’m impressed by his interest in physics and the amount that he has learned so far,” Institute for Advanced Study Professor Scott Tremaine wrote in an email to the family. “The theory that he’s working on involves several of the toughest problems in astrophysics and theoretical physics.”

“Anyone who solves these will be in line for a Nobel Prize,” he added.

{ Time | Continue reading + video }

kids, mathematics, science | May 10th, 2011 6:47 pm

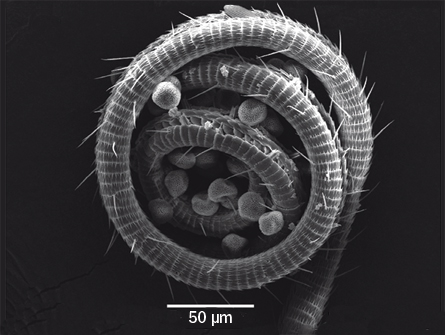

animals, science | May 10th, 2011 6:25 pm

In 1998, two teams of astronomers independently reported amazing and bizarre news: the Universal expansion known for decades was not slowing down as expected, but was speeding up. Something was accelerating the Universe.

Since then, the existence of this something was fiercely debated, but time after time it fought with and overcame objections. Almost all professional astronomers now accept it’s real, but we still don’t know what the heck is causing it. So scientists keep going back to the telescopes and try to figure it out. (…)

We see galaxies rushing away from us. Moreover, the farther away they are, the faster they appear to be moving. The rate of that expansion is what was measured. If you find a galaxy 1 megaparsec away (about 3.26 million light years), the expansion of space would carry it along at 73.8 km/sec (fast enough to cross the United States in about one minute!). A galaxy 2 megaparsecs away would be traveling away at 147.6 km/sec, and so on*.

The last time this was measured accurately, the speed was seen to be 74.2 +/- 3.6 km/sec/mpc. (…)

By knowing this number so well, it allows better understanding of how the Universe is behaving. It also means astronomers can study just how much the Universe deviates from this constant rate at large distances due to the acceleration. And that in turn allows us to throw out some ideas for what dark energy is, and entertain notions of what it might be.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

related { Evidence of Big Bang May Disappear in 1 Trillion Years }

mystery and paranormal, science, space | May 10th, 2011 6:22 pm

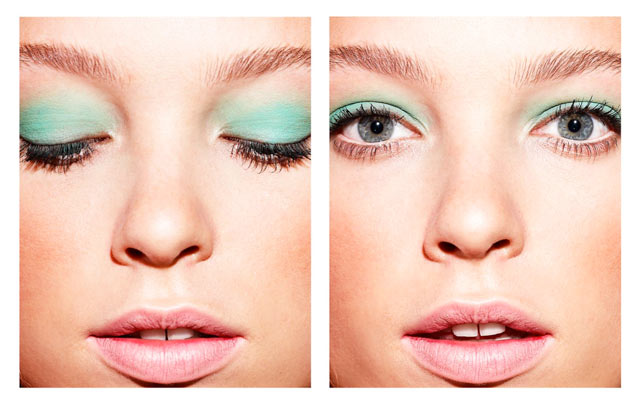

“There are aspects of personality that others know about us that we don’t know ourselves, and vice-versa,” says Vazire. “To get a complete picture of a personality, you need both perspectives.” The paper is published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

It’s not that we know nothing about ourselves. But our understanding is obstructed by blind spots, created by our wishes, fears, and unconscious motives—the greatest of which is the need to maintain a high (or if we’re neurotic, low) self-image, research shows. Even watching ourselves on videotape does not substantially alter our perceptions—whereas others observing the same tape easily point out traits we’re unaware of. (…)

Interestingly, people don’t see the same things about themselves as others see. Anxiety-related traits, such as stage fright, are obvious to us, but not always to others. On the other hand, creativity, intelligence, or rudeness is often best perceived by others.

{ APS | Continue reading }

photo { Hans-Peter Feldmann }

psychology | May 7th, 2011 10:08 am

Do groups have genetic structures? If so, can they be modified?

Those are two central questions for Thomas Malone, a professor of management and an expert in organizational structure and group intelligence at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. (…)

First is the question of whether general cognitive ability — what we think of, when it comes to individuals, as “intelligence” — actually exists for groups. (…)

And what they found is telling. “The average intelligence of the people in the group and the maximum intelligence of the people in the group doesn’t predict group intelligence,” Malone said. Which is to say: “Just getting a lot of smart people in a group does not necessarily make a smart group.” Furthermore, the researchers found, group intelligence is also only moderately correlated with qualities you’d think would be pretty crucial when it comes to group dynamics — things like group cohesion, satisfaction, “psychological safety,” and motivation. It’s not just that a happy group or a close-knit group or an enthusiastic group doesn’t necessarily equal a smart group; it’s also that those psychological elements have only some effect on groups’ ability to solve problems together.

So how do you engineer groups that can problem-solve effectively? First of all, seed them with, basically, caring people. Group intelligence is correlated, Malone and his colleagues found, with the average social sensitivity — the openness, and receptiveness, to others — of a group’s constituents. The emotional intelligence of group members, in other words, serves the cognitive intelligence of the group overall.

{ Nieman Journalism Lab | Continue reading }

photo { Richard Avedon }

psychology, relationships, science | May 7th, 2011 10:08 am

Among the many tissues within the human body, few are more stigmatized than the hymen. This is largely in part due to the human cultural perceptions of the hymen as a measure of sexual status. And while the hymen is well known for the cultural perceptions, few are aware of the actual anatomical and physiological aspects.

Commonly misconceived as a part of the internal vaginal canal, in reality, the hymen is not inside of the vagina at all. The hymen is a membrane-like tissue which is considered part of the external genitalia, whereas the internal vaginal orifice is partly covered by the labia majora.

Although hymens are only present in the female sex, there are variations of the types that may naturally occur. Hymen morphological variation can range from crescent-shaped, ring-shaped, folded upon itself, banded across the opening, holed, or, without an opening within the hymen at all. Such cases are considered “imperforated hymens” and only occur in 1 in 2,000 females.

{ Serious Monkey Business | Continue reading }

photo { Todd Fisher }

science, sex-oriented | May 5th, 2011 1:20 pm

The inscription refers to the most famous public demonstration of ether as an anesthetic during surgery. On October 16th, 1846 a crowd of doctors and students gathered in the surgical amphitheater at Massachusetts General Hospital to watch as a dentist named William T.G. Morton instructed a patient to inhale the fumes from an ether-soaked sponge. After the patient was sufficiently sedated, a surgeon removed a tumor from his neck. When the patient awoke from his ether-induced stupor, the surgeon asked how he felt, to which he reportedly replied, “feels as if my neck’s been scratched.”

{ Smells like science | Continue reading }

installation { Michael Elmgreen & Ingar Dragset, Interstage, 2005 | wax figure, plaster body, iron, aluminium, wood | 300 x 250 x 851 cm }

flashback, science | May 5th, 2011 1:19 pm

A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden shows that the brain has built-in mechanisms that trigger an automatic reaction to someone who refuses to share. The reaction derives from the amygdala, an older part of the brain. The subjects’ sense of justice was challenged in a two-player money-based fairness game, while their brain activity was registered by an MR scanner. When bidders made unfair suggestions as to how to share the money, they were often punished by their partners even if it cost them. A drug that inhibits amygdala activity subdued this reaction to unfairness.

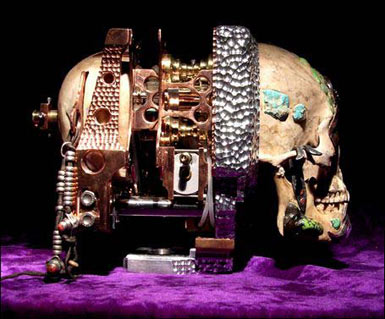

{ Karolinska Institutet | Continue reading }

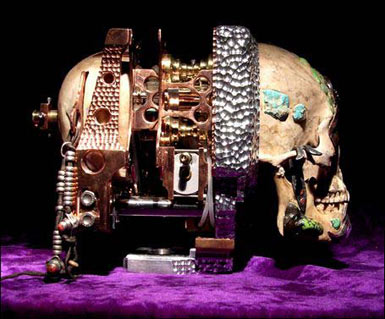

image { Wayne Belger’s Yama (Tibetan Skull Camera) }

neurosciences | May 5th, 2011 1:16 pm

There’s no such thing as a free lunch, and that goes for your brain, too. Every time you amass the willpower to do anything, it has mental costs. (…)

Starting an activity seems to take a larger of willpower and other resources than keeping going with it. Required activation energy can be adjusted over time – making something into a routine lowers the activation energy to do it. (…)

This is a major hurdle for a lot of people in a lot of disciplines – just getting started.

{ LifeHacker | Continue reading }

guide, neurosciences | May 4th, 2011 11:52 am

A new study of itch adds to growing evidence that the chemical signals that make us want to scratch are the same signals that make us wince in pain.

The interactions between itch and pain are only partly understood, said itch and pain researcher Diana Bautista.

The skin contains some nerve cells that respond only to itch and others that respond only to pain. Others, however, respond to both, and some substances cause both itching and pain.

{ UC Berkeley | Continue reading }

science | May 3rd, 2011 6:02 pm

A psychology study from Hong Kong suggests that, among men, the impulses to make love and war are deeply intertwined.

In a 2002 book, Chris Hedges compellingly argued that war is both an addiction and a way of engaging in the sort of heroic struggle that gives our lives meaning.

Evolutionary psychologists, on the other hand, see war as an extension of mating-related male aggression. They argue men compete for status and resources in an attempt to attract women and produce offspring, thereby passing on their genes to another generation. This competition takes many forms, including violence and aggression against other males — an impulse frowned upon by modern society but one that can be channeled into acceptability when one joins the military.

It’s an interesting and well-thought-out theory, but there’s not a lot of direct evidence to back it up. That’s what makes “The Face That Launched a Thousand Ships,” a paper just published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, so intriguing.

A team of Hong Kong-based researchers led by psychologist Lei Chang of Chinese University conducted four experiments that suggest a link between the motivation to mate and a man’s interest in, or support for, war.

{ Miller-McCune | Continue reading }

relationships, science | May 3rd, 2011 3:50 pm

When we think of demographics that are easily distracted, we tend to think of younger generations, people on their phones over dinner or texting while driving, or only listening to you with one ear while they listen to their ipod with the other. But when we’re talking about cognitive tasks like working memory, the ability to work without distractions is actually highest when you’re younger, and decreases with age. Working memory is the ability to store bits of information and manipulate them over a short period of time. How long the working memory lasts for depends on what you’re trying to remember (say, a string of words that makes sense over a string of numbers that doesn’t), the amount of information you’re trying to process, and on how distracted you are.

{ Neurotic Physiology | Continue reading }

memory, neurosciences | May 2nd, 2011 6:10 pm

Recently, scientists have begun to focus on how architecture and design can influence our moods, thoughts and health. They’ve discovered that everything—from the quality of a view to the height of a ceiling, from the wall color to the furniture—shapes how we think. (…)

In 2009, psychologists at the University of British Columbia studied how the color of a background—say, the shade of an interior wall—affects performance on a variety of mental tasks. They tested 600 subjects when surrounded by red, blue or neutral colors—in both real and virtual environments.

The differences were striking. Test-takers in the red environments, were much better at skills that required accuracy and attention to detail, such as catching spelling mistakes or keeping random numbers in short-term memory.

Though people in the blue group performed worse on short-term memory tasks, they did far better on tasks requiring some imagination, such as coming up with creative uses for a brick or designing a children’s toy. In fact, subjects in the blue environment generated twice as many “creative outputs” as subjects in the red one.

{ WSJ | Continue reading }

architecture, colors, psychology | May 2nd, 2011 6:04 pm