A local zoologist, Jamie Seymour, blamed King’s death on a nearly transparent jellyfish the size of a thumbnail. Covered from the top of its head to the tip of its four tentacles with millions of microscopic spring-loaded harpoons filled with venom, it’s one of at least ten related species of small jellyfish whose sting can plunge victims into what doctors call the Irukandji syndrome.

“The symptoms overwhelm you,” says Seymour, 40, who himself was stung by an irukandji on the lip, the only part of his body uncovered as he scuba-dived looking for specimens near an island off Cairns in late 2003. “On a pain scale of 1 to 10, it rated between 15 and 20,” he says, describing the vomiting, the cramps and the feeling of panic. “I was convinced I was going to die.” But he was lucky; not all species of irukandji administer fatal stings, and he recovered within a day. (…)

Most jellyfish are passive; they drift up and down in the water column, or are pulled to and fro by the tides and winds. They float through the oceans devouring tiny fish and microscopic creatures that bumble into their tentacles, and are no threat to humans.

But those known as box jellyfish, for the shape of their bell, or body, are a breed apart. Also called cubozoans, they’re voracious hunters, able to chase prey by moving forward—as well as up and down—at speeds of up to two knots. They range in size from the various irukandji species to their big brother, the brutish Chironex fleckeri, which has a bell the size of a man’s head and up to 180 yards of tentacles, each lined with billions of cells bursting with deadly venom. Also known as a sea wasp or marine stinger, Chironex, which is far deadlier than irukandji, boasts powerful stingers, or nematocysts, strong enough to pierce the carapace of a crab and quick enough to shoot out at the fastest speed known in the natural world—up to 40,000 times the force of gravity. And unlike other jellyfish, a box jellyfish can see where it’s going and alter its course accordingly; like an eerie creature sprung from science fiction or a horror movie, it has four separate brains and 24 eyes, providing it a 360-degree view of its watery world.

“A Chironex fleckeri can kill a human in one minute flat,” says Seymour, widely considered the world’s foremost box jellyfish researcher. (…)

“We hardly know anything about their lifestyle, how they breed, where they come from, how fast they grow, how long they live, or even how many species there are,” says Lisa-ann Gershwin, a 41-year-old California stockbroker-turned-jellyfish taxonomist. “But they’re like other cubozoans: they’re really neat, like aliens. They split from the other jellyfish, the scyphozoa, more than 300 million years ago, long before dinosaurs walked the earth, and have been making their own way along the evolutionary path ever since.” (…)

Death comes quickly to Chironex victims because—unlike venomous snakes, which inject a glob of venom that must pass through the lymphatic system before draining into the rest of the body—Chironex shoots its venom into the bloodstream, giving the venom a direct pathway to the heart.

In addition to their stinging cells, box jellyfish have another superlative weapon in their hunt for prey: one of the world’s most effective sets of eyes.

On a windy day at a beach 40 miles north of Cairns, I help a team led by Dan Nilsson, a zoology professor at Sweden’s Lund University and a renowned expert on animal eyes. (…) “They swim like fish, not like jellyfish,” he says with a smile. He plucks one from the bucket and shows me what keeps it from bumping into things: four tiny black dots, containing the jellyfish’s 24 eyes, on strands connected to each side of the cube of jelly. Under the microscope, Nilsson has detected in each dot something he calls a sensory club, which is an organ with a set of six eyes, including four that are—much like the eyes of other jellyfish—simply pits, limited to detecting light intensity in various directions. But the two other eyes in each sensory club have more in common with human eyes than the eyes of other jellyfish, with lenses, corneas and retinas. One eye, which points obliquely downward at all times, even has a mobile pupil that opens and closes. The other major eye points upward. “We’re not exactly sure what these eyes are doing,” Nilsson says, although he believes they may help the jellyfish “position itself in the right place where there is plenty of food.” They also help the animal situate the shoreline and the horizon—to avoid being dumped on the beach by a wave—and see obstacles that would tear its delicate tissue, such as a coral reef, a mangrove tree or a pier.

They also have the same stomach—or, rather, stomachs. Because a box jelly, as Jamie Seymour puts it, “charges around the ocean all day hunting mobile prey, prawns and fish,” its metabolic rate is ten times that of a drifting jellyfish. So, to swiftly access the energy it needs, the box jellyfish has developed a unique digestive system, with separate stomachs in each of its tentacles. All box jellies turn their food into a semi-digested broth in the bell, and then feed it down through the tentacles to be absorbed. Since a Chironex can have up to 60 tentacles, each as long as 3 yards, in effect it has up to 180 yards of stomach.

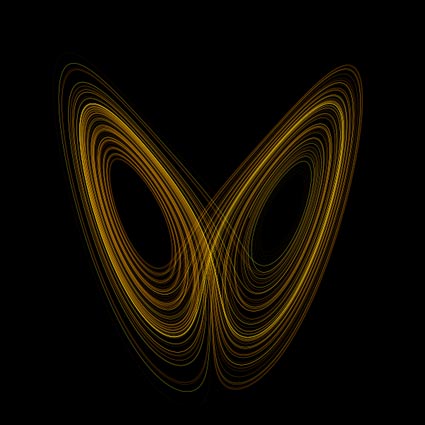

If box jellyfish eyes are a puzzle, its four primitive brains—positioned on each side of its body and attached to it by the same strand that anchors its eyes—are an enigma. Can the four separate brains communicate with each other? If so, do they merge the images they receive from the 24 eyes into one image? And how do they manage if different eyes detect radically different images? Nilsson shrugs. “They’ve evolved a rather advanced system unlike any other animal on earth,” he says. “But we have no idea what’s going on in their four brains, and I suspect it will be a long time before we find out.”

{ Smithsonian | Continue reading }

Despite its primitive structure, the North American comb jellyfish can sneak up on its prey like a high-tech stealth submarine, making it a successful predator. Researchers, including one from the University of Gothenburg, have now been able to show how the jellyfish makes itself hydrodynamically ‘invisible’.

{ PhysOrg | Continue reading }