science

In the first months after her surgery, shopping for groceries was infuriating. Standing in the supermarket aisle, Vicki would look at an item on the shelf and know that she wanted to place it in her trolley — but she couldn’t. “I’d reach with my right for the thing I wanted, but the left would come in and they’d kind of fight,” she says. “Almost like repelling magnets.” Picking out food for the week was a two-, sometimes three-hour ordeal. Getting dressed posed a similar challenge: Vicki couldn’t reconcile what she wanted to put on with what her hands were doing. Sometimes she ended up wearing three outfits at once. “I’d have to dump all the clothes on the bed, catch my breath and start again.”

In one crucial way, however, Vicki was better than her pre-surgery self. She was no longer racked by epileptic seizures that were so severe they had made her life close to unbearable. She once collapsed onto the bar of an old-fashioned oven, burning and scarring her back. “I really just couldn’t function,” she says. When, in 1978, her neurologist told her about a radical but dangerous surgery that might help, she barely hesitated. If the worst were to happen, she knew that her parents would take care of her young daughter. “But of course I worried,” she says. “When you get your brain split, it doesn’t grow back together.”

In June 1979, in a procedure that lasted nearly 10 hours, doctors created a firebreak to contain Vicki’s seizures by slicing through her corpus callosum, the bundle of neuronal fibres connecting the two sides of her brain. This drastic procedure, called a corpus callosotomy, disconnects the two sides of the neocortex, the home of language, conscious thought and movement control. Vicki’s supermarket predicament was the consequence of a brain that behaved in some ways as if it were two separate minds.

After about a year, Vicki’s difficulties abated. “I could get things together,” she says. For the most part she was herself: slicing vegetables, tying her shoe laces, playing cards, even waterskiing.

But what Vicki could never have known was that her surgery would turn her into an accidental superstar of neuroscience. She is one of fewer than a dozen ’split-brain’ patients, whose brains and behaviours have been subject to countless hours of experiments, hundreds of scientific papers, and references in just about every psychology textbook of the past generation. And now their numbers are dwindling.

{ Nature | Continue reading }

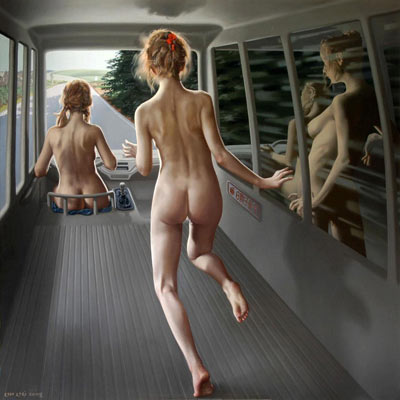

photo { Taylor Radelia }

brain, health, neurosciences | March 15th, 2012 2:10 pm

Putting Helium in a Dolphin. Two opposing hypotheses propose that tonal sounds arise either from tissue vibrations or through actual whistle production from vortices stabilized by resonating nasal air volumes. Here, we use a trained bottlenose dolphin whistling in air and in heliox [a mixture of helium and oxygen] to test these hypotheses.

(…)

Sixty-two percent of the dishwashers were positive for fungi.

(…)

Some years ago a colleague pointed out that there was a connection between paranoid symptomatology and the drawing in of joints on arms and legs on human figure drawings. [A researcher named] Buck states that emphasis upon knees suggests the presence of homosexual tendencies. Over a period of time, this investigator was impressed with the frequent connection between these two variables. This study was designed to determine the validity of this hypothesis.

(…)

In Study 1, 55 young women responded that they preferred men with hairy chests and circumcised penises.

{ Annals of Improbable Research | Special Body Parts Issue | PDF }

dolphins, haha, science | March 15th, 2012 12:52 pm

The memory for odors has been studied mostly from the point of view of odor recognition. In the present work, the memory for odors is studied not from the point of view of recognition but from the hedonic dimension of the sensation aroused by the stimulus.

Hedonicity is how we like or dislike a conscious experience. Hedonicity seems to be especially predominant with olfactory sensation. What will be studied, therefore, is the capacity to remember stimuli as a function of the amount of pleasure or displeasure aroused by the stimuli – in our case, odors. In the following pages, the term “pleasure/displeasure” will be considered as describing the hedonic dimension of consciousness. (…)

The “goodness” of a person’s memory for a given event is known to depend on variables such as the nature of the event, the context within which it occurs, initial encoding and subsequent recoding operations performed on the input, and the extent to which retrieval cues match these operations. It was shown also that slides arousing stronger emotions tended to be better remembered.

The question addressed in the present experiment concerned the role of perceived or felt pleasure or displeasure evoked by the experienced stimulus events. The hypothesis was that the hedonic dimension of cognition, aroused by the events at encoding and stored in memory, plays an important role in remembering of the events.

Pleasure/displeasure and emotion have long been recognized as dominant features in odorant stimulation, description, and memory. EEG recordings demonstrate the deep influence of olfactory stimuli on the brain. “The most important function of the nose may be not in transmitting messages about the outside world, but in motivating the organism after the message has been received” (Engen, 1973); that function being already present in the newborn and even intra utero.

Animal experiments have shown that odors followed by a reward were better remembered than non-rewarded odors, which is a clue that memory privileges usefulness. It was demonstrated also that recollections evoked by odors are more emotional than those evoked verbally, that verbal codes are not necessary for odor-associated memory and finally that pleasant odors enhance approach behavior due to their hedonic dimension. These findings suggest that the sensory stimulus in olfaction should provide a favorable paradigm to test the hypothesis that hedonicity is a potent factor for storing a piece of information into memory.

{ International Journal of Psychological Studies | Continue reading }

olfaction, psychology | March 15th, 2012 7:35 am

images { 1 | 2 }

psychology, relationships | March 14th, 2012 1:13 pm

If you’re looking to enhance your experience of abstract art, you may want to consider spending some pre-gallery time watching a horror film. Kendall Eskine and his colleagues Natalie Kacinik and Jesse Prinz have investigated how different emotions, as well as physiological arousal, influence people’s sublime experiences whilst viewing abstract art. Their finding is that fear, but not happiness or general arousal, makes art seem more sublime.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

art, psychology | March 12th, 2012 3:05 pm

In their 2006 research they compared 40 exotic dancers with a similar number of young adult females who didn’t strip for a living. Using validated surveys, and interviewing both groups, they made some significant findings:

• Strippers had remarkably less satisfaction from their personal relationships and were more likely to think their romantic partnerships would fail

• There was no difference in self-esteem between strippers and non-strippers

• Strippers prized their physical appearance over and above their other qualities and abilities.

• If a stripper felt their body was not beautiful enough, their self-esteem would be affected.

• Strippers seemed to be slightly less satisfied with their body and were more likely to scrutinise their physical appearance. More often they would “be ashamed if people knew what I really weigh”.

{ Dr Stu’s Blog | Continue reading }

psychology | March 12th, 2012 2:39 pm

Getting older makes us happier, because we give up on our dreams

Although physical quality of life goes down after middle age, mental satisfaction increases.

The study of more than 10,000 people in Britain and the US adds support to a previous report that happiness levels form a U-curve, hitting their low point at around 45, then rising.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading }

psychology | March 12th, 2012 2:24 pm

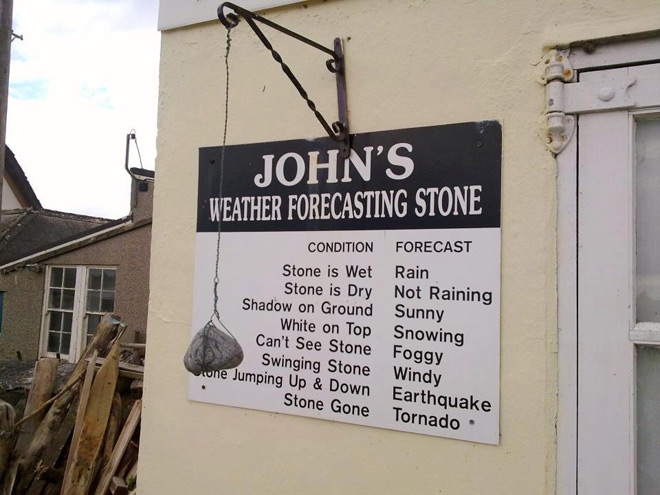

climate, haha | March 12th, 2012 10:51 am

In his groundbreaking 1995 book Descartes’ Error, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio describes Elliott, a patient who had no problem understanding information, but who nonetheless could not live a normal life. Elliott passed every standard intelligence test with flying colors. But he was dysfunctional because he was missing one thing: his cognitive brain couldn’t converse with his emotional brain. An operation to control violent seizures had severed the connection between Elliott’s prefrontal cortex, the area behind the forehead that plays a key role in making decisions, and the limbic area down near the brain stem, which is involved with emotions.

As a result, Elliott had the facts, but he couldn’t use them to make decisions. Without feelings to give the facts valence they were useless. Indeed, Elliott teaches us that in the most precise sense of the word, facts are meaningless…just disconnected ones and zeroes in the computer until we run them through the software of how those facts feel. Of all the building evidence about human cognition that suggests we ought to be a little more humble about our ability to reason, no other finding has more significance, because Elliott teaches us that no matter how smart we like to think we are, our perceptions are inescapably a blend of reason and gut reaction, intellect and instinct, facts and feelings.

{ Big Think | Continue reading }

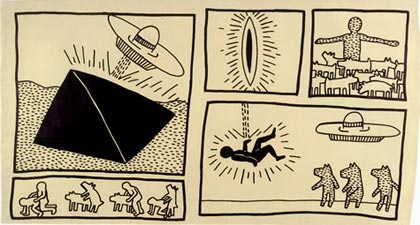

artwork { Keith Haring }

brain, experience, neurosciences | March 9th, 2012 2:20 pm

Cancer is a puzzle of staggering complexity. Every move towards a solution seems to reveal yet another layer of mystery.

For a start, cancer isn’t a single disease, so we can dispense with the idea of a single “cure”. There are over 200 different types, each with their own individual quirks. Even for a single type – say, breast cancer – there can be many different sub-types that demand different treatments. Even within a single subtype, one patient’s tumour can be very different from another’s. They could both have very different sets of mutated genes, which can affect their prognosis and which drugs they should take.

{ NERS/Discover | Continue reading }

health, science | March 9th, 2012 2:15 pm

One thing I’ve learned in the five years I’ve spent studying viruses is that these little things are genetic brewing machines. They can carry genetic material from different organisms, they can integrate in the host’s genome, they can transport genetic material from one organism to another. The viral genome of a flu virus in particular is split in different portions called segments. Now suppose an avian flu virus and a swine flu virus infect the same hosts, and two viral particles coinfect the same cell inside the host. Yes, you’ve guessed it: the genetic segments from the two distinct viruses can indeed “reshuffle” and create a completely new virus. In the case of H1N1, this pattern of coinfection and “reshuffling” (called segment reassortment) happened more than once and across three different hosts: birds, pigs, and humans.

{ Chimeras | Continue reading }

health, science | March 9th, 2012 2:04 pm

Sperm Can Do ‘Calculus’ to Calculate Calcium Dynamics and React Accordingly

Sperm have only one aim: to find the egg. The egg supports the sperm in their quest by emitting attractants. Calcium ions determine the beating pattern of the sperm tail which enables the sperm to move. Scientists have discovered that sperm react to changes in calcium concentration, but not to the calcium concentration itself. Probably sperm make this calculation so that they remain capable of maneuvering even in the presence of high calcium concentrations.

{ Science Daily | Continue reading }

quote { Barnard, Columbia at War Over Obama, Feminazis, and Cum Dumpsters | via Joe! }

science, sex-oriented | March 9th, 2012 2:00 pm

photogs, space | March 8th, 2012 3:02 pm

In one experiment, the psychologists asked a group of Christian students to give their impressions of the personalities of two people. In all relevant respects, these two people were very similar – except one was a fellow Christian and the other Jewish. Under normal circumstances, participants showed no inclination to treat the two people differently. But if the students were first reminded of their mortality (e.g., by being asked to fill in a personality test that included questions about their attitude to their own death) then they were much more positive about their fellow Christian and more negative about the Jew.

The researchers behind this work – Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg and Tom Pyszczynski – were testing the hypothesis that most of what we do we do in order to protect us from the terror of death; what they call “Terror Management Theory.” Our sophisticated worldviews, they believe, exist primarily to convince us that we can defeat the Reaper. Therefore when he looms, scythe in hand, we cling all the more firmly to the shield of our beliefs.

This research, now spanning over 400 studies, shows what poets and philosophers have long known: that it is our struggle to defy death that gives shape to our civilization. (…)

The psychologists, psychiatrists and anthropologists who developed Terror Management Theory have shown that almost all ideologies, from patriotism to communism to celebrity culture, function similarly in shielding us from death’s approach. (…)

In one now classic secular example, the researchers recruited court judges from Tucson in the USA. Half of these judges were reminded of their mortality (again with the otherwise innocuous personality test) and half were not. They were then all asked to rule on a hypothetical case of prostitution similar to those they ruled on every day. The judges who had first been reminded of their mortality set a bond (the equivalent of bail) nine times higher than those who hadn’t (averaging $455 compared to $50).

So just like the Christians, they reacted to the thought of death by clinging more fiercely to their worldview.

{ New Humanist | Continue reading }

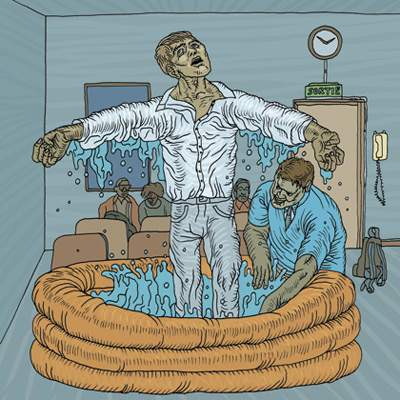

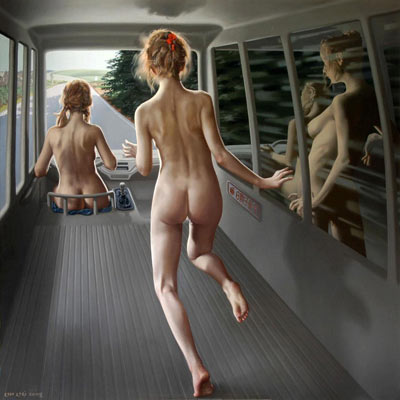

artwork { Lui Liu }

ideas, psychology | March 7th, 2012 4:14 pm

Common sense or ‘folk psychology‘ is what your average person in the street uses to make sense of human behaviour. It says people have affairs because their relationship is unsatisfying, that people steal because they want money and that people give to charity because they want to help people.

Scientists tend to say ‘well, it’s a bit more complicated than that’ but talk of conditional risk factors for behaviour won’t get you very far in a dinner table discussion so ‘folk psychology’ is a culturally agreed form of psychology that is acceptable to use in everyday explanation.

I’ve just been alerted to a fascinating study in the journal Public Understanding of Science looks at how the enthusiasm for pop neuroscience has encroached on ‘folk psychology’ to create a form of ‘folk neuropsychology’ where brain-based explanations are now becoming acceptable in everyday explanation.

{ Mindhacks | Continue reading }

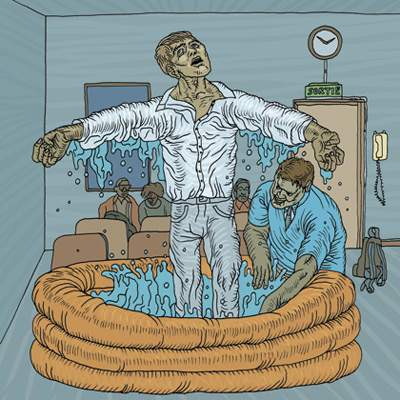

artwork { Pole Edouard }

neurosciences | March 5th, 2012 1:23 pm

Whenever we are doing something, one of our brain hemispheres is more active than the other one. However, some tasks are only solvable with both sides working together.

PD Dr. Martina Manns and Juliane Römling of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum are investigating, how such specializations and co-operations arise. Based on a pigeon-model, they are proving for the first time in an experimental way, that the ability to combine complex impressions from both hemispheres, depends on environmental factors in the embryonic stage. (…)

First the pigeons have to learn to discriminate the combinations A/B and B/C with one eye, and C/D and D/E with the other one. Afterwards, they can use both eyes to decide between, for example, the colours B/D. However, only birds with embryonic light experience are able to solve this problem.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

Imagine the smell of an orange. Have you got it? Are you also picturing the orange, even though I didn’t ask you to? Try fish. Or mown grass. You’ll find it’s difficult to bring a scent to mind without also calling up an image. It’s no coincidence, scientists say: Your brain’s visual processing center is doing double duty in the smell department.

{ Inkfish | Continue reading }

birds, brain, eyes, olfaction | March 5th, 2012 1:20 pm

Having adequate personal space is an important aspect of users’ comfort with their environment. In a restaurant, for instance, spatial intrusion by others can lead to avoidance responses such as early departure or a disinclination to spend.

A web-based survey of more than 1,000 Americans elicited behavioral intentions and emotional responses to a projected restaurant experience when parallel dining tables were spaced at six, twelve, and twenty-four inches apart under three common dining scenarios. Respondents strongly objected to closely spaced tables in most circumstances, particularly in a “romantic” context. Not only did the respondents react negatively to tightly spaced tables but they were generally disdainful of banquette- style seating, regardless of table distance.

The context of the dining experience (e.g., a business lunch, a family occasion) is likely to be a key factor in consumers’ preferences for table spacing and their subsequent behaviors. Gender was also a factor, as women were much less comfortable than men in tight quarters. The findings are clear but the implications for restaurateurs are not, because a tight table arrangement has been demonstrated to shorten the dining cycle without affecting spending.

{ SAGE | Continue reading }

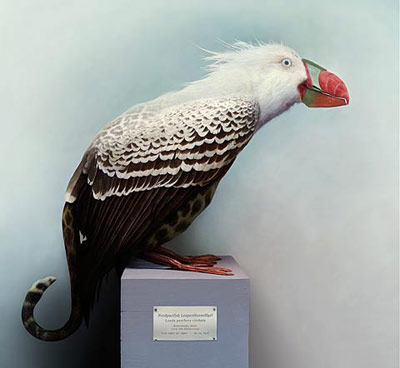

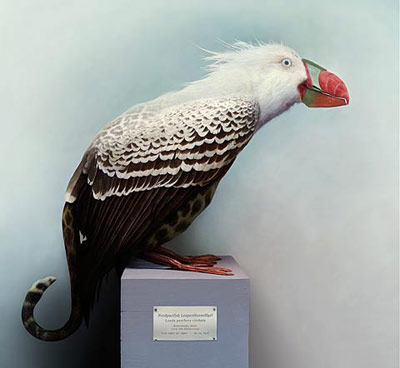

image { Desiree Dolron }

related { Monsters, daemons, and devils: The Accusations of Nineteenth-Century Vegetarian Writers | PDF }

economics, food, drinks, restaurants, relationships, science | March 1st, 2012 2:08 pm

The most destructive of the defense mechanisms are those that involve being deeply out of touch with reality. (…) A classic example is delusion. (…) Another example is denial, an inability to accept reality, both publicly and privately, a classic example being denial of a drug or alcohol addiction. (…)

Even for the healthiest among us, reality can be a bit too harsh to confront head on, but Level 4 defense mechanisms are considered to be generally functional. Some examples include humor, which is sometimes the best way to cope with emotional pain, and sublimation, which involves transforming unacceptable desires into constructive and socially acceptable forms, such as creating art, embarking on a spiritual path, running a marathon, becoming a dentist…

{ Psych Your Mind | Continue reading }

image { Nam June Paik, 9/23/69: Experiment with David Atwood, 1969 }

psychology | February 29th, 2012 3:14 pm

When people have positive experiences with members of another group, they tend to generalize these experiences from the group member to the group as a whole. This process of member-to-group generalization results in less prejudice against the group. Notably, however, researchers have tended to ignore what happens when people have negative experiences with group members.

In a recent article, my colleagues and I proposed that negative experiences have an opposite but stronger effect on people’s attitudes towards groups.

{ Mark Rubin | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships | February 29th, 2012 3:05 pm

Scientists are attempting to clarify the path that leads to consciousness by following a single, bite-sized piece of information — the redness of an apple, for instance — as it moves into a person’s inner mind.

Recent research into the visual system suggests that a sight simply passing through the requisite vision channels in the brain isn’t enough for an experience to form. Studies that delicately divorce awareness from the related, but distinct, process of attention call into question the role of one of the key stops on the vision pipeline in creating conscious experience.

Other experiments that create the sensation of touch or hearing through sight alone hint at the way in which different kinds of inputs come together. So far, scientists haven’t followed enough individual paths to get a full picture. But they are hot on the trail, finding clues to how the brain builds conscious experience.

One of the best-understood systems in the brain is the complex network of nerve cells and structures that allow a person to see. Imprints on cells in the eye’s retina get shuttled to the thalamus, to the back of the brain and then up the ranks to increasingly specialized cells where color, motion, location and identity of objects are discerned.

After decades of research, today’s map of the vision system looks like a bowl of spaghetti thrown on the floor, with long, elegant lines connected by knotty tangles. But there’s an underlying method in this ocular madness: Information appears to flow in a prescribed direction.

After planting a vision in a person’s retina, scientists can then watch how one image moves through the brain. By asking viewers when they become aware of the vision, researchers may pinpoint where along the pipeline it pops into consciousness.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

brain, eyes, neurosciences | February 28th, 2012 11:48 am