science

So Wiseman has written a self-help book of his own, a collection of techniques built on findings from academic research in psychology.

Call it evidence-based self-help. The book is called 59 Seconds, for the time it’s supposed to take to practice each of the bits of advice Wiseman lays out within: Looking to seduce someone? Take your date to an amusement park or on a vigorous run, for research shows that attraction increases along with heart rate. Think someone’s prone to telling you white lies? Correspond more with them by e-mail, for research shows people are less likely to prevaricate when there’s a written record that could trip them up later.

{ Freakonomics | Continue reading | Interview }

books, guide, psychology | January 28th, 2010 5:22 pm

What is a “mental illness”? What is an “illness”? What does the description and classification of “mental illnesses” actually involve, and is the description of “new” mental illnesses description of actually existing entities, or the creation of them?

“Solastalgia” is a neologism, invented by the Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, to give greater meaning and clarity to psychological distress caused by environmental change. …) The doctor and former British Foreign Secretary, Lord Owen, has coined the phrase “hubris syndrome” to describe the mindset of prime ministers and presidents whose behaviour is characterised by reckless, hubristic belief in their own rightness.

This paper uses both the concept of solastalgia and the related concepts Albrecht posited of psychoterratic and somaterratic illnesses and hubris syndrome as a starting point to explore issues around the meaning of mental illness, and what it means to describe and classify mental illness.

{ Seamus P. MacSuibhne, What makes “a new mental illness”?: The cases of solastalgia and hubris syndrome | Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy | Continue reading }

quote { Thanks Robert }

health, ideas, psychology | January 28th, 2010 5:21 pm

“When a man sits with a pretty girl for an hour,” said Albert Einstein, “it seems like a minute. But let him sit on a hot stove for a minute, and it’s longer than any hour.” Einstein was describing one of the most profound implications of his Theory of General Relativity - that the perception of time is subjective. This is something we all know from experience: time flies when we are enjoying ourselves, but seems to drag on when we are doing something tedious.

The subjective experience of time can also be manipulated experimentally. Visual stimuli which appear to be approaching are perceived to be longer in duration than when viewed as static or moving away. Similarly, participants presented with a stream of otherwise identical stimuli, but including one oddball (or “deviant”) stimulus, tend to perceive the deviant stimulus as lasting longer than the others. The underlying neural mechanisms of this are unknown, but now the first neuroimaging study of this phenomenon implicates the involvement of brain structures which are thought to be required for cognitive control and subjective awareness.

The apparent prolonged duration of a looming or deviant stimulus is referred to as the time dilation illusion, and three possible, but not mutually exclusive, explanations for why it might occur have been put forward. First, the stimulus might be perceived as lasting longer because it has unusual properties which require an increased amount of attention to be devoted to it. Alternatively, the perceived duration of the stimulus might reflect the amount of energy expended in generating its neural representation (that is, duration is a function of coding efficiency). Finally, the effect might be due to the intrinsic dynamic properties of the stimulus, such that the brain estimates time based on the number of changes in an event.

{ Neurophilosophy/ScienceBlogs | Continue reading }

psychology, science, time | January 28th, 2010 5:20 pm

Our memories are strengthened during periods of rest while we are awake, researchers at New York University have found. The findings expand our understanding of how memories are boosted—previous studies had shown this process occurs during sleep, but not during times of awake rest.

“Taking a coffee break after class can actually help you retain that information you just learned,” explained Lila Davachi, an assistant professor in NYU’s Department of Psychology and Center for Neural Science, in whose laboratory the study was conducted. “Your brain wants you to tune out other tasks so you can tune in to what you just learned.”

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

science | January 28th, 2010 5:14 pm

The relationship between emotions and rationality is one that has preoccupied man for thousands of years. As the ancient Stoics said, the emotions typically involve the judgement that harm or benefit is at hand (Sorabji 2006). Already, then, there was thought to be a relationship between emotions and ‘judgement’, the latter implying a degree of rationality. But Sorabji, a philosopher, also points out that the mere intellectual appreciation of benefit or harm does not constitute emotion, but there must be some physiological disturbance: disembodied emotion is not meaningful. Yet the physiological reactions involved in emotions are typically thought of, since the development of evolutionary theory, as something of more primitive origins than reasoning. One reaction to this would be to argue that emotions govern actions that are urgent and essential to survival, whereas reasoning is dispassionate and calculating. (…)

To understand the usefulness of neuroscience in examining the rationality of decision-making, it is worth looking at an example. Current neurological research shows that people with orbitofrontal cortical lesions have difficulties in anticipating the negative emotional consequences of their choices. People with healthy brains, however, seem to take account of these emotions, which are mediated through and are consistent with counterfactual thinking in the assessment of choice alternatives (Bechara et al. 1994). More generally, results from psychological and neurological research show that emotions and affective states are not just sources of biased judgements, but may also serve as essential functions leading to more appropriate choices.

{ Alan Kirman, Pierre Livet and Miriam Teschl | Continue reading | More: Theme Issue ‘Rationality and emotions’ | The Royal Society B }

photo { Ansen Seale }

brain, ideas, psychology, science | January 21st, 2010 8:35 pm

{ 1 | 2 }

showbiz, space, visual design | January 21st, 2010 8:27 pm

What do we know about the relationship between mental illness and jazz?

A review of biographical material of 40 famous jazz musicians of the period from 1945 to 1960 excluding those who were still alive, was studied and rated for psychiatric diagnoses according to the DSM IV classification.

Results:

• 10% (4) had family psychiatric disorder

• 17,5% (7) had unhappy or unstable early lifes

• 52,5% (21) were addicted to heroin some time during their lives.

• 27,5 (11) were dependent on alcohol and 15% (6) abused alcohol

• 8% (3) were dependent on cocaine

• 8% (3) had psychotic disorder

• 28,5% (11) had mood disorders

• 5% (2) had anxiety disorders

• 17,5% (7) had sentsation seeking tendencies such as disinhibition and thrill and adventure seeking. This has been linked to borderline personality disorder

• 2 killed themselfs later in life

{ Dr. Shock | Continue reading }

music, psychology | January 21st, 2010 8:24 pm

Physicists and cosmologists have long noted that the laws of physics seem remarkably well tuned to allow the existence of life, an idea known as the anthropic principle.

It is sometimes used to explain why the laws of physics are the way they are. Answer: because if they were different, we wouldn’t be here to see them.

To many people, that looks like a cop out. One problem is that this way of thinking is clearly biased towards a certain kind of carbon-based life that has evolved on a pale blue dot in an unremarkable corner of the cosmos. Surely there is a more objective way to explain the laws of physics.

Enter Raphael Bousso and Roni Harnik at the University of California, Berkeley and Stanford University respectively. They point out that the increase in entropy in any part of the Universe is a decent measure of the complexity that exists there. Perhaps the anthropic principle can be replaced with an entropic one?

Today, they outline their idea and it makes a fascinating read. By thinking about the way entropy increases, Bousso and Harnik derive the properties of an average Universe in which the complexity has risen to a level where observers would have evolved to witness it.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

photo { Jocelyn Lee }

ideas, science | January 21st, 2010 8:21 pm

The brain processes fearful faces more quickly when seen out of the corner of the eye than when viewed straight on. Dimitri Bayle and colleagues, who made their finding using magnetoencephalography (MEG) brain scanning, believe this bias has probably evolved because threats are more likely to come from side-on.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

eyes, psychology, science | January 21st, 2010 8:16 pm

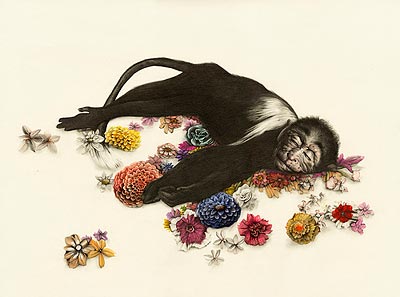

I stopped eating pork about eight years ago, after a scientist happened to mention that the animal whose teeth most closely resemble our own is the pig. Unable to shake the image of a perky little pig flashing me a brilliant George Clooney smile, I decided it was easier to forgo the Christmas ham. A couple of years later, I gave up on all mammalian meat, period. I still eat fish and poultry, however and pour eggnog in my coffee. My dietary decisions are arbitrary and inconsistent, and when friends ask why I’m willing to try the duck but not the lamb, I don’t have a good answer. Food choices are often like that: difficult to articulate yet strongly held. (…)

But before we cede the entire moral penthouse to “committed vegetarians” and “strong ethical vegans,” we might consider that plants no more aspire to being stir-fried in a wok than a hog aspires to being peppercorn-studded in my Christmas clay pot.

Plants are lively and seek to keep it that way. The more that scientists learn about the complexity of plants — their keen sensitivity to the environment, the speed with which they react to changes in the environment, and the extraordinary number of tricks that plants will rally to fight off attackers and solicit help from afar — the more impressed researchers become, and the less easily we can dismiss plants as so much fiberfill backdrop, passive sunlight collectors on which deer, antelope and vegans can conveniently graze. (…)

Just because we humans can’t hear them doesn’t mean plants don’t howl. Some of the compounds that plants generate in response to insect mastication — their feedback, you might say — are volatile chemicals that serve as cries for help. Such airborne alarm calls have been shown to attract both large predatory insects like dragon flies, which delight in caterpillar meat, and tiny parasitic insects, which can infect a caterpillar and destroy it from within.

{ Natalie Angier/NY Times | Continue reading }

illustration { Kirsty Whiten }

Botany, food, drinks, restaurants | January 21st, 2010 8:16 pm

Bayesian probability is a great model of rationality that gets lots of important things right, but there are two ways in which its simple version, the one that comes most easily to mind, is extremely misleading.

One way is that it is too easy to assume that all our thoughts are conscious – in fact we are aware of only a tiny fraction of what goes on in our minds, perhaps only one part in a thousand. We have to deal with not only “running on error-prone hardware”, but worse, relying on purposely misleading inputs. Our subconscious often makes coordinated efforts to mislead us on particular topics. (…)

We may see one part in a thousand of our minds, but that fraction pales by comparison to the fact that we are each only one part in seven billion of living humanity.

Taking this fact seriously requires even bigger changes to how we think about rationality. OK, we don’t need to consider it for topics that only we can influence. But for most interesting important topics, it matters far more what the entire world does than what we personally do.

{ OvercomingBias | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | January 21st, 2010 8:15 pm

Tom alerted me to this fantastic brief case published in the British Medical Journal where a builder is admitted to hospital in great pain after a nail penetrated all the way through his boot. But it turned out that the pain was entirely psychological, as the nail had missed his foot by sliding between his toes. (…)

This isn’t really the nocebo effect, where ’side-effects’ appear after having taken nothing but a placebo, but more similar to what doctors might describe in its persistent form as somatisation disorder where physical symptoms appear that aren’t explained by tissue damage.

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading }

incidents, psychology | January 21st, 2010 8:09 pm

‘Grid cells’ that act like a spatial map in the brain have been identified for the first time in humans, according to new research by UCL scientists which may help to explain how we create internal maps of new environments. (…)

Grid cells represent where an animal is located within its environment, which the researchers liken to having a satnav in the brain.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Jocelyn Lee }

brain, science | January 21st, 2010 8:07 pm

{ The notion that the speed of thought could be measured, just like the density of a rock, was shocking. Yet that is exactly what scientists did. | Discover | Full story }

brain, science, weirdos | January 21st, 2010 8:06 pm

Analyses of classic authors’ works provide a way to “linguistically fingerprint” them, researchers say.

The relationship between the number of words an author uses only once and the length of a work forms an identifier for them, they argue.

Analyses of works by Herman Melville, Thomas Hardy, and DH Lawrence showed these “unique word” charts are specific to each author.

Researchers also suggest each author pulls their works from a hypothetical “meta book”. One description of this concept might be a framework for the way an author uses language. It is from this framework that all their works are ultimately derived.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

photo { Andy Tew }

books, ideas, science | January 21st, 2010 8:04 pm

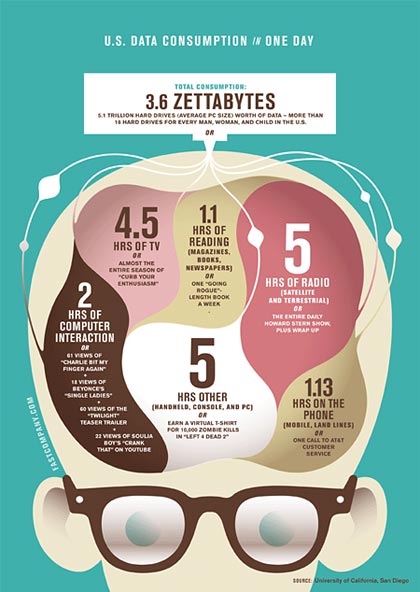

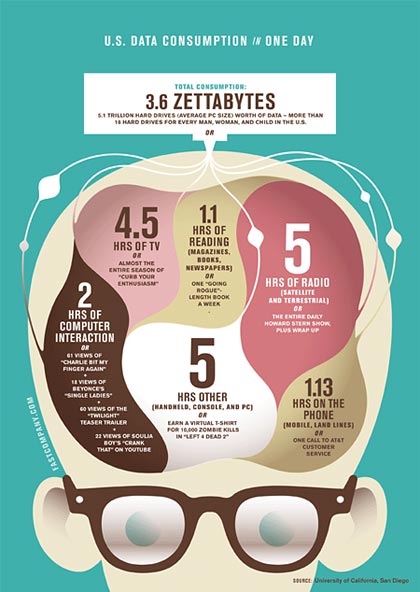

{ How much data do Americans consume each day? | Good | Enlarge }

brain, visual design | January 21st, 2010 8:03 pm

Are you a media multitasker? We know you’re reading a blog, but what else are you doing right now? Take a quick inventory: Are you also listening to music? Monitoring the progress of a sports game on TV? Emailing your co-worker? Texting your friend? On hold with tech support? If your inventory has revealed a multitasking lifestyle, you are not alone. Media multitasking is increasingly common, to the extent that some have dubbed today’s teens “Generation M.” (…)

However, new research suggests that people who multitask suffer from a problem: weaker self-control ability.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

science | January 14th, 2010 6:20 pm

We use coin tosses to settle disputes and decide outcomes because we believe they are unbiased with 50-50 odds.

Yet recent research into coin flips has discovered that the laws of mechanics determine the outcome of coin tosses: The startling finding is they aren’t random. Instead, for natural flips, the chance of a coin coming up on the same side as it started is about 51 percent. Heads facing up predicts heads; tails facing up predicts tails.

{ The Big Money | Continue reading }

mathematics | January 14th, 2010 6:11 pm

Are pillow fights more dangerous than roller coasters?

A paper compared head motions that occurred in 4 participants when they rode 3 different roller coasters, drove bumper cars, and had a pillow fight. What are the implications for brain injury? they asked. (…) “The highest level of rotational acceleration was measured during the pillow fight. Interestingly, the pillow fight generated peak head accelerations and velocities greater than the 3 roller coaster rides.”

{ Neurocritic | Continue reading }

brain, health, leisure, science | January 14th, 2010 6:10 pm

I also learned of Kandinsky’s growing love affair with the circle. The circle, he wrote, is “the most modest form, but asserts itself unconditionally.” It is “simultaneously stable and unstable,” “loud and soft,” “a single tension that carries countless tensions within it.” (…)

Quirkily enough, the artist’s life followed a circular form: He was born in December 1866, and he died the same month in 1944. This being December, I’d like to honor Kandinsky through his favorite geometry, by celebrating the circle and giving a cheer for the sphere. Life as we know it must be lived in the round, and the natural world abounds in circular objects at every scale we can scan. Let a heavenly body get big enough for gravity to weigh in, and you will have yourself a ball. Stars are giant, usually symmetrical balls of radiant gas, while the definition of both a planet like Jupiter and a plutoid like Pluto is a celestial object orbiting a star that is itself massive enough to be largely round.

On a more down-to-earth level, eyeballs live up to their name by being as round as marbles, and, like Jonathan Swift’s ditty about fleas upon fleas, those soulful orbs are inscribed with circular irises that in turn are pierced by circular pupils. Or think of the curved human breast and its bull’s-eye areola and nipple.

{ Natalie Angier/NY Times | Continue reading }

art, eyes, ideas | January 14th, 2010 6:10 pm