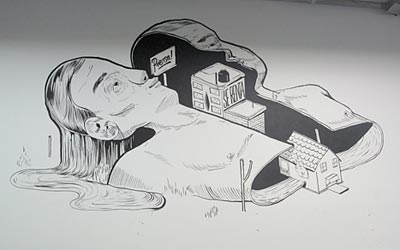

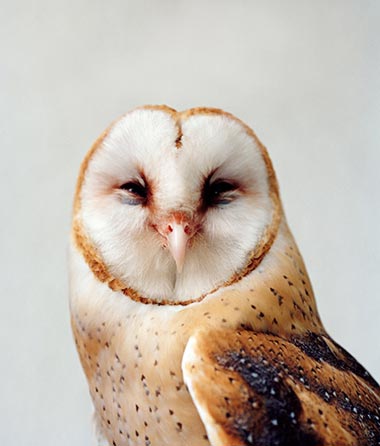

Hegel wrote in his Elements of the Philosophy of Right that the owl of Minerva flies only at night. It hoots at insomniacs. I know. I’m one. (…)

Insomnia has intrigued thinkers since the ancients, an interest that continues today, especially in Europe. (…)

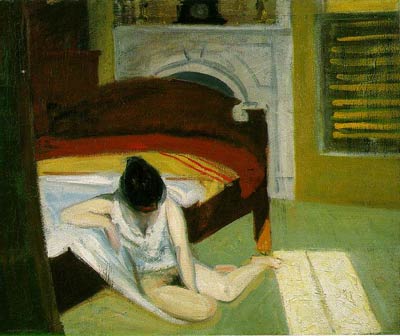

Philosophy is no friend of sleep. In his Laws (circa 350 BC), Plato platonized, “When a man is asleep, he is no better than if he were dead; and he who loves life and wisdom will take no more sleep than is necessary for health.” (…) In Beyond Good and Evil (1886), Nietzsche preached that the high goal of good Europeans “is wakefulness itself.”

Aristotle said all animals sleep. In the 20th century, the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran added in On the Heights of Despair (first published in 1934): “Only humanity has insomnia.” Emmanuel Levinas, author of the erotic and metaphysical Totality and Infinity (1961), imagined philosophy, all of it, to be a call to “infinite responsibility, to an untiring wakefulness, to a total insomnia.” (…)

The first thing you learn about insomnia is that it sees in the dark. The second is that it sees nothing.

{ The Chronicle of Higher Education | Continue reading }

We all know that we don’t get enough sleep. But how much sleep do we really need? Until about 15 years ago, one common theory was that if you slept at least four or five hours a night, your cognitive performance remained intact; your body simply adapted to less sleep. But that idea was based on studies in which researchers sent sleepy subjects home during the day — where they may have sneaked in naps and downed coffee.

Enter David Dinges, the head of the Sleep and Chronobiology Laboratory at the Hospital at University of Pennsylvania, who has the distinction of depriving more people of sleep than perhaps anyone in the world.

In what was the longest sleep-restriction study of its kind, Dinges and his lead author, Hans Van Dongen, assigned dozens of subjects to three different groups for their 2003 study: some slept four hours, others six hours and others, for the lucky control group, eight hours — for two weeks in the lab. (…)

For most of us, eight hours of sleep is excellent and six hours is no good, but what about if we split the difference? (…)

Belenky’s nine-hour subjects performed much like Dinges’s eight-hour ones. But in the seven-hour group, their response time on the P.V.T. slowed and continued to do so for three days, before stabilizing at lower levels than when they started. (…)

Not every sleeper is the same, of course: Dinges has found that some people who need eight hours will immediately feel the wallop of one four-hour night, while other eight-hour sleepers can handle several four-hour nights before their performance deteriorates. There is a small portion of the population — he estimates it at around 5 percent or even less — who, for what researchers think may be genetic reasons, can maintain their performance with five or fewer hours of sleep. (There is also a small percentage who require 9 or 10 hours.)

{ NY Times | Continue reading }