mystery and paranormal

It’s weird to think that tens of thousands of years ago, humans were mating with different species—but they were. That’s what DNA analyses tell us. When the Neanderthal genome was sequenced in 2010, it showed that as much as 1 to 4 percent of the DNA of non-Africans might have been inherited from Neanderthals.

Scientists also announced last year that our ancestors had mated with another extinct species, and this week, more evidence is showing how widespread that interbreeding was.

We know little about this extinct species. In fact, we don’t even have a scientific name for it; for now, the group is simply known as the Denisovans.

{ Smithsonian Magazine | Continue reading }

flashback, genes, mystery and paranormal, science | November 4th, 2011 11:10 am

haha, mystery and paranormal | September 24th, 2011 3:20 pm

Paranormal experiences – whether it’s a psychic or an out-of-body experience or seeing a ghost – may not tell you anything about the world of the supernatural, because that world doesn’t exist, but those experiences still tell you about how your brain and mind operate. (…)

Tell us about his $1 million prize.

He has a long-standing financial reward if anyone can prove under test conditions that they’re psychic. There are various people who act as testers for him in various countries – I’m one of them in the UK. I’ve tested a few people. And it probably says something about the psychic world that in the 10 years that the prize has been up for grabs, no-one has come even close to claiming it. I tested a woman called Patricia Putt who was convinced she could give psychic readings for people, and that they would recognise their past and present in those readings. So we had lots of people come in, she would write down her readings, then we showed them to people and said you had to choose yours out of all of them. And suddenly they were at a loss. That’s because when you go for a psychic reading you know it’s meant for you. You’re sitting there, there are all these ambiguous comments, you can read into them and suddenly be impressed. Once you take away that mechanism everything collapses. (…) A million dollars – quite a large sum of money – is sitting there waiting for the first psychic who can prove they have these abilities. (…)

Does the soul weigh 21 grams?

That is where the movie title comes from. This was an American psychologist around the turn of the 20th century who put dogs onto scales, trying to weigh their souls leaving. He had some success with that, then tried the same with humans – putting very old people on the scales and waiting for them to die. But what he didn’t control for is sweating, moisture leaving the body. So 21 grams is probably much closer to the amount of moisture you lose when you die than your soul.

What exactly is a near-death experience?

A near-death experience is very similar to an out-of-body experience, which is where people think they’re floating away from their body, turned around seeing their body lying there. In a near-death experience, there is often a tunnel of light you go down towards meeting your maker. The gods you see depend very much on the culture you live in. Then the god turns you back, you return into your body and you wake up.

As we know more about how the brain creates a sense of where it is, we know more about how these experiences can be created. Now there are experiments where we can create an out-of-body experience fairly rapidly. Other researchers – and Mary Roach talks about these – write target numbers or words on pieces of cardboard and place them on top of cabinets and wardrobes in hospital wards, in the hope that somebody having a near-death or out-of-body experience will look down and see them. To date they haven’t. Which again suggests that this is an illusion rather than a genuine experience.

{ Richard Wiseman/The Browser | Continue reading }

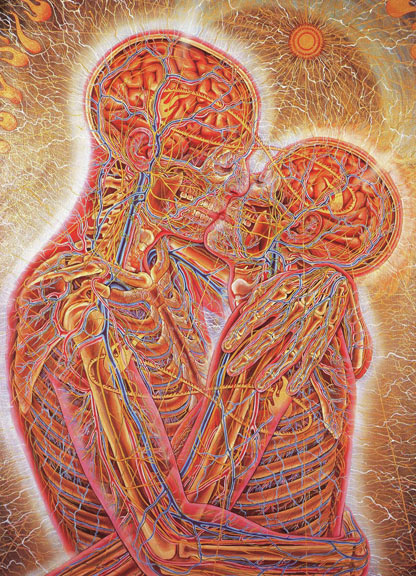

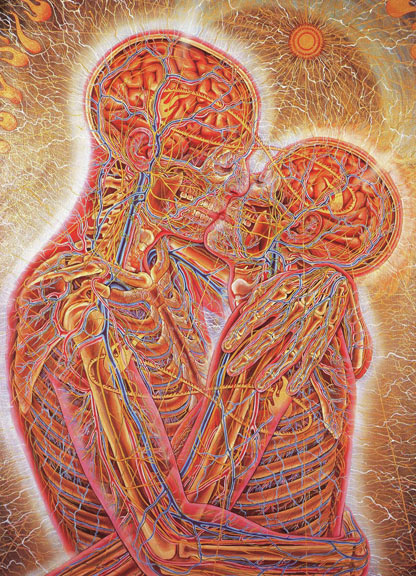

artwork { Alex Grey, Kissing, 1983 }

mystery and paranormal, psychology | September 22nd, 2011 9:48 pm

What makes up 95 percent of the universe?

The answer to the most basic of questions—what’s out there?—has been undergoing constant revision for millennia. (…) It turns out that atoms and other particles we know and understand only make up about 5 percent of the whole shebang. (…)

Why do we need sleep?

Two prevailing theories argue that sleep either restores the energy we need to thrive, or it helps us adapt to threats. Both concepts turn on the idea that evolution made us sleep for a reason. (…)

How do we come to make decisions?

Like all matters relating to gray matter, the answers aren’t clear. “We probably don’t know 99 percent about how the brain does what it does,” says Charles “Ed” Connor, a professor of neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins Brain Science Institute. Still, researchers are making great inroads in understanding things at the cellular and molecular levels, he adds. They understand that the brain collects information delivered by the senses, and when that data reaches a critical mass, parts of the prefrontal cortex act as judge and jury, leading us to come to a conclusion. (…)

When will an earthquake strike? (…)

Are we alone?

{ Johns Hopkins Magazine | Continue reading }

mystery and paranormal, science | September 9th, 2011 1:42 pm

According to Descartes’ model, any real understanding of the body could only come from taking it apart, just as one takes apart a machine to discover its inner workings. If we wish to understand how a clock tells time, according to this model, our job is to disassemble it. Understanding a clock means understanding its springs and gears. And the same is true of living “machines.”

This notion of the body as a machine would clear away centuries of intellectual detritus: By arguing that the body was the sum of its interacting parts, and, more importantly, by suggesting that the study of those parts would reveal the workings of the body, Descartes shifted centuries of scientific and philosophical discussion about imponderable life forces and inexplicable animist vapors. (Lest we go overboard in praising Descartes, he clearly panicked at the last moment. He exempted human beings from the ground rules he set for other living organisms. In so doing, he sowed 400 years of confusion and discord with his notion that the mind and the body were separate phenomena, governed by separate rules.) (…)

But living systems are not really clocklike in their assembly, and organisms are not really machines. (…) The number of elements that compose any living system—an ecosystem, an organism, an organ or a cell—is enormous. In living systems, the specific identities of these component parts matter. Unlike chemistry, for instance, in which an electron in a lithium atom is identical to an electron in a gold atom, all proteins in a cell are not equivalent or interchangeable. Each protein is the result of its own evolutionary trajectory. We understand and exploit their similarities, but their differences matter to us just as much. Perhaps most importantly, the relations between the components of living systems are complex, context-dependent and weak. In mechanical machines, the conversation taking place between the parts involves clear and unambiguous interactions. These interactions result in simple causes and effects: They are instructions barked down a simple chain of command.

In living systems, by contrast, virtually every interesting bit of biological machinery is embedded in a very large web of weak interactions. And this network of interactions gives rise to a discussion among the parts that is less like a chain of command and more like a complex court intrigue: ambiguous whispers against a noisy and distracting background. As a result, the same interaction between a regulatory protein and a segment of DNA can lead to different (and sometimes opposite) outcomes depending on which other proteins are present in the vicinity. The firing of a neuron can act to amplify the signal coming from other neurons or act instead to suppress it, based solely on the network in which the neuron is embedded. (…)

We have revealed the elegant workings of neurons in exquisite detail, but the material understanding of consciousness remains elusive. We have sequenced human genomes in their entirety, but the process that leads from a genome to an organism is still poorly understood. We have captured the intricacies of photosynthesis, and yet the consequences of rising carbon-dioxide levels for the future of the rain forests remain frustratingly hazy.

{ American Scientist | Continue reading }

ideas, mystery and paranormal, science | September 1st, 2011 4:40 pm

The majority of people reading this sentence will, at some point in their lives, undergo a medical treatment that requires general anesthesia. Doctors will inject them with a drug, or have them breathe it in. For several hours, they will be unconscious. And almost all of them will wake up happy and healthy.

We know that the general anesthetics we use today are safe. But we know that because they’ve proven themselves to be safe, not because we understand the mechanisms behind how they work. The truth is, at that level, anesthetics are a big, fat question mark.

{ Boing Boing | Continue reading }

health, mystery and paranormal, sleep | September 1st, 2011 4:05 pm

It wasn’t until the latter half of the 17th century that the first truly scientific account of female ejaculation would be presented, this by a Dutch gynecologist named Reinjier De Graaf, precisely distinguishing between vaginal lubrication, which facilitates intercourse, and female ejaculation, which is tantamount to seminal emission. “This liquid was clearly not designed by Nature to moisten the urethra (as some people think),” wrote De Graaf, describing the “pituito-serous juice” sometimes excreted around the time of female orgasm. (…)

Fast-forward to 1952, past the historical hordes of women secretly ejaculating in mass confusion, and we arrive at the offices of German-born gynecologist Ernest Gräfenberg, who, while the contributions of De Graaf and others are often overlooked, is credited with “discovering” an erotic zone on the anterior wall of the vagina running along the course of the urethra. Ernest, in other words, is the one who first christened your “G-spot.” (…)

It wasn’t until 1982 that female ejaculate was first chemically analyzed. If it’s not urine, and it’s not semen, then what, exactly, is it? (…) It’s rather odd that we still don’t have a name for this substance that 40 percent of women report having produced liberally at least once in their lives.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

mystery and paranormal, science, sex-oriented | August 30th, 2011 6:04 pm

Take a piece of paper. Crumple it. Before you sink a three-pointer in the corner wastebasket, consider that you’ve just created an object of extraordinary mathematical and structural complexity, filled with mysteries that physicists are just starting to unfold.

“Crush a piece of typing paper into the size of a golf ball, and suddenly it becomes a very stiff object. The thing to realize is that it’s 90 percent air, and it’s not that you designed architectural motifs to make it stiff. It did it itself,” said physicist Narayan Menon of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “It became a rigid object. This is what we are trying to figure out: What is the architecture inside that creates this stiffness?”

{ Wired | Continue reading }

image { Richard Smith, Diary, 1975 }

mystery and paranormal, science | August 26th, 2011 9:44 am

{ The most valuable coin in the world sits in the lobby of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in lower Manhattan. It’s Exhibit 18E, secured in a bulletproof glass case with an alarm system and an armed guard nearby. The 1933 Double Eagle, considered one of the rarest and most beautiful coins in America, has a face value of $20—and a market value of $7.6 million. | How did a Philadelphia family get hold of $40 million in gold coins, and why has the Secret Service been chasing them for 70 years? | Businessweek | full story }

U.S., economics, mystery and paranormal | August 26th, 2011 9:40 am

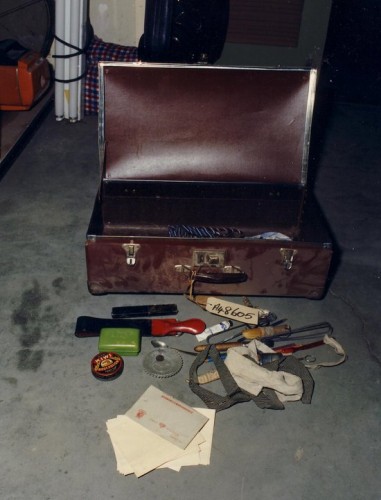

{ What we can say is that the clues in the Somerton Beach mystery (or the enigma of the “Unknown Man”) add up to one of the world’s most perplexing cold cases. It may be the most mysterious of them all. | Smithsonian | full story }

flashback, incidents, mystery and paranormal | August 17th, 2011 3:35 pm

In the early 1970s, NASA sent two spacecraft on a roller coaster ride towards the outer Solar System. Pioneer 10 and 11 travelled past Jupiter (and Saturn in Pioneer 11’s case) and are now heading out into interstellar space.

But in 2002, physicists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, noticed a puzzling phenomenon. The spacecraft are slowing down. Nobody knows why but NASA analysed 11 years of tracking data for Pioneer 10 and 3 years for Pioneer 11 to prove it.

This deceleration, called “the Pioneer anomaly,” has become one of the biggest problems in astrophysics. One idea is that gravity is different at theses distances (Pioneers 10 and 11 are now at 30 and 70 AU [Astronomical Units]). That would be the most exciting conclusion.

But before astrophysicists can accept this, other more mundane explanations have to be ruled out. Chief among these is the possibility that the deceleration is caused by heat from the spacecraft’s radioactive batteries, which may radiate more in one direction than another.

{ The Physics arXiv Blog | Continue reading }

mystery and paranormal, science, space | July 22nd, 2011 4:44 pm

There is this fountain of youth inside the adult brain that actively makes new neurons. Yet we don’t know how this fountain is constructed or maintained.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

photo { Allan Macintyre }

brain, mystery and paranormal, science | July 13th, 2011 5:12 pm

Villagers belonging to an Amazonian group called the Mundurucú intuitively grasp abstract geometric principles despite having no formal math education, say psychologist Véronique Izard of Université Paris Descartes and her colleagues.

Mundurucú adults and 7- to 13-year-olds demonstrate as firm an understanding of the properties of points, lines and surfaces as adults and school-age children in the United States and France, Izard’s team reports.

These results suggest two possible routes to geometric knowledge. “Either geometry is innate but doesn’t emerge until around age 7 or geometry is learned but must be acquired on the basis of general experiences with space, such as the ways our bodies move,” Izard says.

Both possibilities present puzzles, she adds. If geometry relies on an innate brain mechanism, it’s unclear how such a neural system generates abstract notions about phenomena such as infinite surfaces and why this system doesn’t fully kick in until age 7. If geometry depends on years of spatial learning, it’s not known how people transform real-world experience into abstract geometric concepts — such as lines that extend forever or perfect right angles — that a forest dweller never encounters in the natural world.

{ Science News | Continue reading }

artwork { Richard Serra }

brain, mathematics, mystery and paranormal, science | May 25th, 2011 5:15 pm

In 1998, two teams of astronomers independently reported amazing and bizarre news: the Universal expansion known for decades was not slowing down as expected, but was speeding up. Something was accelerating the Universe.

Since then, the existence of this something was fiercely debated, but time after time it fought with and overcame objections. Almost all professional astronomers now accept it’s real, but we still don’t know what the heck is causing it. So scientists keep going back to the telescopes and try to figure it out. (…)

We see galaxies rushing away from us. Moreover, the farther away they are, the faster they appear to be moving. The rate of that expansion is what was measured. If you find a galaxy 1 megaparsec away (about 3.26 million light years), the expansion of space would carry it along at 73.8 km/sec (fast enough to cross the United States in about one minute!). A galaxy 2 megaparsecs away would be traveling away at 147.6 km/sec, and so on*.

The last time this was measured accurately, the speed was seen to be 74.2 +/- 3.6 km/sec/mpc. (…)

By knowing this number so well, it allows better understanding of how the Universe is behaving. It also means astronomers can study just how much the Universe deviates from this constant rate at large distances due to the acceleration. And that in turn allows us to throw out some ideas for what dark energy is, and entertain notions of what it might be.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

related { Evidence of Big Bang May Disappear in 1 Trillion Years }

mystery and paranormal, science, space | May 10th, 2011 6:22 pm

The process of development is an astounding journey from simplicity to complexity. You start with a single cell, the fertilized egg, and you end up with a complete multicellular organism, made up of tissues that self-organize from many individual cells of different types. The question of how cells know who to be and where to go has many layers to it, starting with the question of how you lay down the basic body plan (head here, tail there, which side is left and where does the heart go?) and continuing on down to microscopic structures, with questions such as how and where to form the small tubes that will allow blood to permeate through apparently solid tissues. This kind of self-organizing behavior is deeply interesting to robotics researchers (who would love to copy it) and tissue engineers (who would like to manipulate it).

A recent paper (Parsa et al. 2011. Uncovering the behaviors of individual cells within a multicellular microvascular community) takes a close look at self-organization on the micro level. (…)

Despite the tremendous variability in the paths followed by individual cells, the authors hoped to find patterns in their data that might provide insight into how the network forms. And luckily, the patterns were there to find. Using a clustering algorithm, they identified groups of cells that behaved similarly to each other with respect to specific sets of behavioral parameters. For example, looking at the pattern of how the area of a cell grows and shrinks allowed the authors to define three major clusters of cells that accounted for about 2/3 of the cells in their study. In the same way, they could define subsets of cells that moved through the gel in similar ways. Although these clusters are rather broadly defined, they seem to be telling us something important about differences between the cells in the different subsets; the subset of cells that spread early (with areas showing a peak at 60 or 120 minutes) are more likely to end up as connection points in the network, while the cells that spread late (300 minutes) tend to end up as branches between the connection points.

{ It takes 30 | Continue reading }

photo { Charlie Engman }

mystery and paranormal, science | April 6th, 2011 6:06 pm

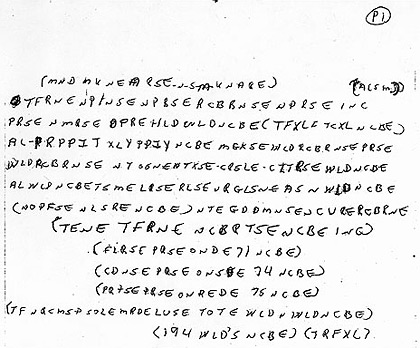

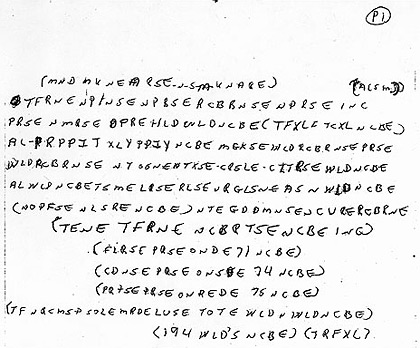

On June 30, 1999, sheriff’s officers in St. Louis, Missouri discovered the body of 41-year-old Ricky McCormick. He had been murdered and dumped in a field. The only clues regarding the homicide were two encrypted notes found in the victim’s pants pockets.

Despite extensive work by our Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit (CRRU), as well as help from the American Cryptogram Association, the meanings of those two coded notes remain a mystery to this day, and Ricky McCormick’s murderer has yet to face justice. (…)

The more than 30 lines of coded material use a maddening variety of letters, numbers, dashes, and parentheses.

{ FBI.gov | Continue reading }

related { Kryptos, a sculpture by Jim Sanborn commissioned by the CIA. Since its dedication on November 3, 1990, there has been much speculation about the meaning of the encrypted messages it bears. Of the four sections, three have been solved, with the fourth remaining one of the most famous unsolved codes in the world. | Wired | Wikipedia | Thanks Tim }

mystery and paranormal | March 31st, 2011 5:27 pm

The most familiar domain, though arguably not the most important to the Earth’s overall biosphere, is the eukaryotes. These are the animals, the plants, the fungi and also a host of single-celled creatures, all of which have complex cell nuclei divided into linear chromosomes.

Then there are the bacteria—familiar as agents of disease, but actually ecologically crucial. Some feed on dead organic matter. Some oxidise minerals. And some photosynthesise, providing a significant fraction (around a quarter) of the world’s oxygen. Bacteria, rather than having complex nuclei, carry their genes on simple rings of DNA which float around inside their cells.

The third great domain of life, the archaea, look, under a microscope, like bacteria. For that reason, their distinctiveness was recognised only in the 1970s. Their biochemistry, however, is very different from that of bacteria (they are, for example, the only organisms that give off methane as a waste product), and their separate history seems to stretch back billions of years.

But is that it? Or are there other biological domains hiding in the shadows—missed, like the archaea were for so long, because biologists have been using the wrong tools to look? A paper published in the Public Library of Science suggests there might indeed be at least one other, previously hidden, domain of life.

{ The Economist | Continue reading }

mystery and paranormal, science | March 27th, 2011 5:00 pm

It’s about Professor Daryl Bem and his cheerful case for ESP.

According to “Feeling the Future,” a peer-reviewed paper the APA’s Journal of Personality and Social Psychology will publish this month, Bem has found evidence supporting the existence of precognition. (…)

Responses to Bem’s paper by the scientific community have ranged from arch disdain to frothing rejection. And in a rebuttal—which, uncommonly, is being published in the same issue of JPSP as Bem’s article—another scientist suggests that not only is this study seriously flawed, but it also foregrounds a crisis in psychology itself. (…)

Over seven years, Bem measured what he considers statistically significant results in eight of his nine studies. In the experiment I tried, the average hit rate among 100 Cornell undergraduates for erotic photos was 53.1 percent. (Neutral photos showed no effect.) That doesn’t seem like much, but as Bem points out, it’s about the same as the house’s advantage in roulette. (…)

“It shouldn’t be difficult to do one proper experiment and not nine crappy experiments,” the University of Amsterdam’s Eric-Jan Wagenmakers, co-author of the rebuttal, says. (…)

Before PSI, Bem made his biggest splash in the nonacademic world with a politically incorrect but weirdly compelling theory of sexual orientation. In 1996, he published “Exotic Becomes Erotic” in Psychological Review, arguing that neither gays nor straights are “born that way”—they’re born a certain way, and that’s what eventually determines their sexual preference.

“I think what the genes code for is not sexual orientation but rather a type of personality,” he explains. According to the EBE theory, if your genes make you a traditionally “male” little boy, a lover of sports and sticks, you’ll fit in with other boys, so what will be exotic to you—and, eventually, erotic—are females. On the other hand, if you’re sensitive, flamboyant, performative, you’ll be alienated from other boys, so you’ll gravitate sexually toward your exotic—males.

EBE is not exactly universally accepted.

{ NY mag | Continue reading }

photos { Irina Werning, Back to the future, Mechi 1990 & 2010, Buenos Aires | more }

controversy, mystery and paranormal, psychology | March 2nd, 2011 7:09 pm

As a trained statistician with degrees from MIT and Stanford University, Srivastava was intrigued by the technical problem posed by the lottery ticket. In fact, it reminded him a lot of his day job, which involves consulting for mining and oil companies. A typical assignment for Srivastava goes like this: A mining company has multiple samples from a potential gold mine. Each sample gives a different estimate of the amount of mineral underground. “My job is to make sense of those results,” he says. “The numbers might seem random, as if the gold has just been scattered, but they’re actually not random at all. There are fundamental geologic forces that created those numbers. If I know the forces, I can decipher the samples. I can figure out how much gold is underground.”

Srivastava realized that the same logic could be applied to the lottery. The apparent randomness of the scratch ticket was just a facade, a mathematical lie. And this meant that the lottery system might actually be solvable, just like those mining samples. (…)

The North American lottery system is a $70 billion-a-year business, an industry bigger than movie tickets, music, and porn combined. (…)

It took a few hours of studying his tickets and some statistical sleuthing, but he discovered a defect in the game: The visible numbers turned out to reveal essential information about the digits hidden under the latex coating. Nothing needed to be scratched off—the ticket could be cracked if you knew the secret code.

{ Wired | Continue reading }

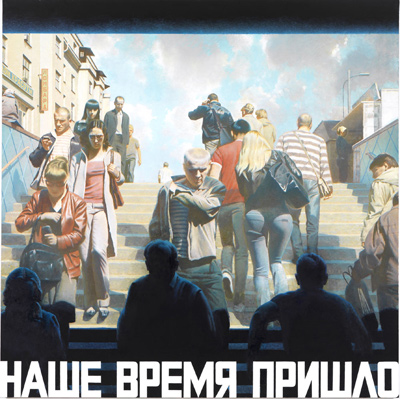

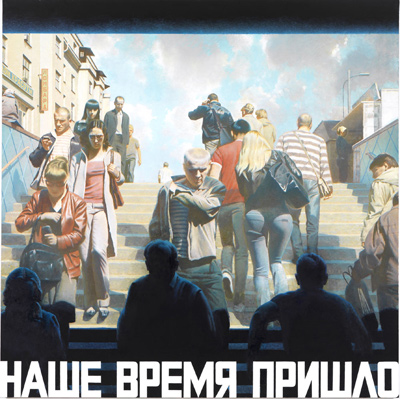

artwork { Erik Bulatov }

mathematics, mystery and paranormal | February 1st, 2011 4:19 pm

Over the last several months, 22,741 New Yorkers contacted the city’s Department of Sanitation and arranged for the pickup of refrigerators, air-conditioners and freezers. In more than 11,000 instances, the machines vanished before sanitation workers arrived in their white trucks to pick them up.

Who, then, is stealing the household appliances of New York City?

Scavengers, to be sure, abound in New York, especially during tough economic times. But the sheer magnitude of the thefts — 11,528 appliances, to be precise — over a relatively brief period suggests to some in city government and the recycling industry that a more organized enterprise may be at work as well.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

mystery and paranormal, new york | January 28th, 2011 2:21 pm