brain

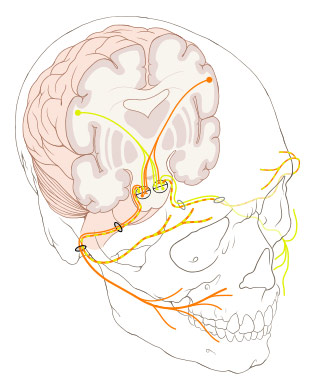

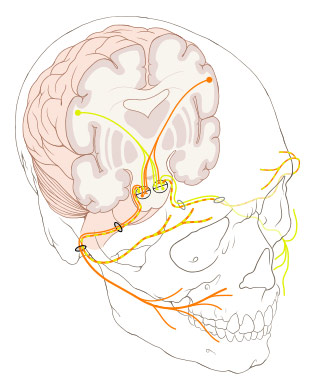

Scientists report that they have mapped the physical architecture of intelligence in the brain. Theirs is one of the largest and most comprehensive analyses so far of the brain structures vital to general intelligence and to specific aspects of intellectual functioning, such as verbal comprehension and working memory. (…)

“We found that general intelligence depends on a remarkably circumscribed neural system,” Barbey said. “Several brain regions, and the connections between them, were most important for general intelligence.”

These structures are located primarily within the left prefrontal cortex (behind the forehead), left temporal cortex (behind the ear) and left parietal cortex (at the top rear of the head) and in “white matter association tracts” that connect them.

The researchers also found that brain regions for planning, self-control and other aspects of executive function overlap to a significant extent with regions vital to general intelligence.

The study provides new evidence that intelligence relies not on one brain region or even the brain as a whole, Barbey said, but involves specific brain areas working together in a coordinated fashion.

{ University of Illinois | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | April 10th, 2012 2:02 pm

Since quite a long time neuroscientists know where the process of creative thinking takes place in the brain: mainly in the frontal lobe. The part of the brain behind our forehead is responsible for the production of ideas that are not only original, rare and uncommon but also appropriate, thus useful and adaptive. Against that background, findings about impairments in creative cognition as a consequence of frontal lobe damages are not surprising.

The neuroscientists Shamay-Tsoory et al. however, looked at this relation a little bit closer. Lesions in the frontal lobe do not always entail negative consequences for creativity. Rather on the contrary.

{ United Academics | Continue reading }

artwork { Femke Hiemstra }

brain, ideas | March 26th, 2012 1:12 pm

Neuroscientists know that the brain contains some 100 billion neurons and that the neurons are joined together via an estimated quadrillion (one million billion) connections. It’s through those links that the brain does the remarkable work of learning and storing memory. Yet scientists have never mapped that whole web of neural contact, known as the connectome. It would be as if doctors knew about each of our bones in isolation but had never seen an entire skeleton. The sheer complexity of the connectome has put such a map out of reach until now.

{ Discover | Continue reading }

related { Is a project to map the brain’s full communications network worth the money? }

illustration { Trevor Brown }

brain, neurosciences | March 23rd, 2012 12:01 pm

The hippocampus is the part of the brain that’s responsible for learning, storing memories and associating them with feelings and emotions. Within the hippocampus lies the dentate gyrus, which is where adult neurogenesis takes place — the formation of new neurons throughout adulthood. The middle layer of the dentate gyrus contains a type of neurons called granule cells. These are constantly generated and take a few weeks to develop and integrate in the dentate gyrus network.

Marin-Burgin et al. asked the following question:

Is it solely the continuous addition of new neurons to the network that is important, or are there specific functional properties only attributable to new granule cells (GCs) that are relevant to information processing?

{ Chimeras | Continue reading }

brain, memory, neurosciences | March 16th, 2012 3:00 pm

In the first months after her surgery, shopping for groceries was infuriating. Standing in the supermarket aisle, Vicki would look at an item on the shelf and know that she wanted to place it in her trolley — but she couldn’t. “I’d reach with my right for the thing I wanted, but the left would come in and they’d kind of fight,” she says. “Almost like repelling magnets.” Picking out food for the week was a two-, sometimes three-hour ordeal. Getting dressed posed a similar challenge: Vicki couldn’t reconcile what she wanted to put on with what her hands were doing. Sometimes she ended up wearing three outfits at once. “I’d have to dump all the clothes on the bed, catch my breath and start again.”

In one crucial way, however, Vicki was better than her pre-surgery self. She was no longer racked by epileptic seizures that were so severe they had made her life close to unbearable. She once collapsed onto the bar of an old-fashioned oven, burning and scarring her back. “I really just couldn’t function,” she says. When, in 1978, her neurologist told her about a radical but dangerous surgery that might help, she barely hesitated. If the worst were to happen, she knew that her parents would take care of her young daughter. “But of course I worried,” she says. “When you get your brain split, it doesn’t grow back together.”

In June 1979, in a procedure that lasted nearly 10 hours, doctors created a firebreak to contain Vicki’s seizures by slicing through her corpus callosum, the bundle of neuronal fibres connecting the two sides of her brain. This drastic procedure, called a corpus callosotomy, disconnects the two sides of the neocortex, the home of language, conscious thought and movement control. Vicki’s supermarket predicament was the consequence of a brain that behaved in some ways as if it were two separate minds.

After about a year, Vicki’s difficulties abated. “I could get things together,” she says. For the most part she was herself: slicing vegetables, tying her shoe laces, playing cards, even waterskiing.

But what Vicki could never have known was that her surgery would turn her into an accidental superstar of neuroscience. She is one of fewer than a dozen ’split-brain’ patients, whose brains and behaviours have been subject to countless hours of experiments, hundreds of scientific papers, and references in just about every psychology textbook of the past generation. And now their numbers are dwindling.

{ Nature | Continue reading }

photo { Taylor Radelia }

brain, health, neurosciences | March 15th, 2012 2:10 pm

In his groundbreaking 1995 book Descartes’ Error, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio describes Elliott, a patient who had no problem understanding information, but who nonetheless could not live a normal life. Elliott passed every standard intelligence test with flying colors. But he was dysfunctional because he was missing one thing: his cognitive brain couldn’t converse with his emotional brain. An operation to control violent seizures had severed the connection between Elliott’s prefrontal cortex, the area behind the forehead that plays a key role in making decisions, and the limbic area down near the brain stem, which is involved with emotions.

As a result, Elliott had the facts, but he couldn’t use them to make decisions. Without feelings to give the facts valence they were useless. Indeed, Elliott teaches us that in the most precise sense of the word, facts are meaningless…just disconnected ones and zeroes in the computer until we run them through the software of how those facts feel. Of all the building evidence about human cognition that suggests we ought to be a little more humble about our ability to reason, no other finding has more significance, because Elliott teaches us that no matter how smart we like to think we are, our perceptions are inescapably a blend of reason and gut reaction, intellect and instinct, facts and feelings.

{ Big Think | Continue reading }

artwork { Keith Haring }

brain, experience, neurosciences | March 9th, 2012 2:20 pm

Whenever we are doing something, one of our brain hemispheres is more active than the other one. However, some tasks are only solvable with both sides working together.

PD Dr. Martina Manns and Juliane Römling of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum are investigating, how such specializations and co-operations arise. Based on a pigeon-model, they are proving for the first time in an experimental way, that the ability to combine complex impressions from both hemispheres, depends on environmental factors in the embryonic stage. (…)

First the pigeons have to learn to discriminate the combinations A/B and B/C with one eye, and C/D and D/E with the other one. Afterwards, they can use both eyes to decide between, for example, the colours B/D. However, only birds with embryonic light experience are able to solve this problem.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

Imagine the smell of an orange. Have you got it? Are you also picturing the orange, even though I didn’t ask you to? Try fish. Or mown grass. You’ll find it’s difficult to bring a scent to mind without also calling up an image. It’s no coincidence, scientists say: Your brain’s visual processing center is doing double duty in the smell department.

{ Inkfish | Continue reading }

birds, brain, eyes, olfaction | March 5th, 2012 1:20 pm

Scientists are attempting to clarify the path that leads to consciousness by following a single, bite-sized piece of information — the redness of an apple, for instance — as it moves into a person’s inner mind.

Recent research into the visual system suggests that a sight simply passing through the requisite vision channels in the brain isn’t enough for an experience to form. Studies that delicately divorce awareness from the related, but distinct, process of attention call into question the role of one of the key stops on the vision pipeline in creating conscious experience.

Other experiments that create the sensation of touch or hearing through sight alone hint at the way in which different kinds of inputs come together. So far, scientists haven’t followed enough individual paths to get a full picture. But they are hot on the trail, finding clues to how the brain builds conscious experience.

One of the best-understood systems in the brain is the complex network of nerve cells and structures that allow a person to see. Imprints on cells in the eye’s retina get shuttled to the thalamus, to the back of the brain and then up the ranks to increasingly specialized cells where color, motion, location and identity of objects are discerned.

After decades of research, today’s map of the vision system looks like a bowl of spaghetti thrown on the floor, with long, elegant lines connected by knotty tangles. But there’s an underlying method in this ocular madness: Information appears to flow in a prescribed direction.

After planting a vision in a person’s retina, scientists can then watch how one image moves through the brain. By asking viewers when they become aware of the vision, researchers may pinpoint where along the pipeline it pops into consciousness.

{ ScienceNews | Continue reading }

brain, eyes, neurosciences | February 28th, 2012 11:48 am

Let me tell you about the problem confronting us. The brain is a 1.5 kilogram mass of jelly, the consistency of tofu, you can hold it in the palm of your hand, yet it can contemplate the vastness of space and time, the meaning of infinity and the meaning of existence. It can ask questions about who am I, where do I come from, questions about love and beauty, aesthetics, and art, and all these questions arising from this lump of jelly. It is truly the greatest of mysteries. The question is how does it come about?

When you look at the structure of the brain it’s made up of neurons. Of course, everybody knows that these days. There are 100 billion of these nerve cells. Each of these cells makes about 1,000 to 10,000 contacts with other neurons. From this information people have calculated that the number of possible brain states, of permutations and combinations of brain activity, exceeds the number of elementary particles in the universe.

The question is how do you go about studying this organ? (…)

Here’s a person who is perfectly coherent, intelligent, can discuss politics with you, can discuss mathematics with you, play chess with you, asserting that his left arm doesn’t belong to him. (…)

If they can label you, give your syndrome a name, they can charge you, charge an insurance company, so there has been a tendency to multiply syndromes.

There’s one called, by the way, Chronic Underachievement Syndrome, which in my day used to be called stupidity. It actually has a name and it’s officially recognized. Then there is a syndrome called De Clerambault Syndrome. De Clerambault Syndrome refers to, believe it or not, a young woman developing an obsession with a much older, famous, eminent, rich guy and develops the delusion that that guy is madly in love with her but is in denial about it. This is actually found in a textbook of psychiatry, and I think it’s complete nonsense. Ironically, there’s no name for the converse of the syndrome where an aging male develops a delusion that this young hottie is madly in love with him, but is in denial about it. Surely, it’s much more common and yet it doesn’t have a name. Right?

{ Edge | Continue reading }

artwork { Keith Haring }

brain, neurosciences | February 22nd, 2012 4:19 pm

Nurturing a child early in life may help him or her develop a larger hippocampus, the brain region important for learning, memory and stress responses, a new study shows.

{ Cosmos | Continue reading }

Previous animal research showed that early maternal support has a positive effect on a young rat’s hippocampal growth, production of brain cells and ability to deal with stress. Studies in human children, on the other hand, found a connection between early social experiences and the volume of the amygdala, which helps regulate the processing and memory of emotional reactions. Numerous studies also have found that children raised in a nurturing environment typically do better in school and are more emotionally developed than their non-nurtured peers.

Brain images have now revealed that a mother’s love physically affects the volume of her child’s hippocampus. In the study, children of nurturing mothers had hippocampal volumes 10 percent larger than children whose mothers were not as nurturing. Research has suggested a link between a larger hippocampus and better memory.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

photo { Jeanne Buechi }

brain, kids, relationships | January 31st, 2012 10:48 am

Group settings can diminish expressions of intelligence, especially among women

Research led by scientists at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute found that small-group dynamics — such as jury deliberations, collective bargaining sessions, and cocktail parties — can alter the expression of IQ in some susceptible people. “You may joke about how committee meetings make you feel brain dead, but our findings suggest that they may make you act brain dead as well,” said Read Montague, who led the study.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

brain, ideas, psychology | January 23rd, 2012 5:42 pm

The brain’s ability to function can start to deteriorate as early as 45, suggests a study in the British Medical Journal.

University College London researchers found a 3.6% decline in mental reasoning in women and men aged 45-49.

Previous research had suggested that cognitive decline does not begin much before the age of 60.

{ BBC | Continue reading }

photo { Larry Sultan }

brain, health | January 6th, 2012 9:56 am

There are two different types of alcohol-induced blackout: en bloc, a complete loss of memory for the affected time period; and fragmentary, where bits and pieces of memories remain. The en bloc blackout is more likely to occur when a large quantity of alcohol is ingested within a small time period.

(…)

Alcohol primarily interferes with the ability to form new long–term memories, leaving intact previously established long–term memories and the ability to keep new information active in memory for brief periods. … Blackouts are much more common among social drinkers—including college drinkers—than was previously assumed, and have been found to encompass events ranging from conversations to intercourse. Mechanisms underlying alcohol–induced memory impairments include disruption of activity in the hippocampus, a brain region that plays a central role in the formation of new autobiographical memories.

(…)

Women are more susceptible to alcohol blackouts than men (and recover more slowly) because of their generally less muscular body composition, and gender differences in pharmacokinetics.

{ The Neurocritic | Continue reading }

brain, food, drinks, restaurants, genders, health | January 2nd, 2012 7:06 am

According to research funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, nearly 25 percent of older adults had small pockets of dead brain cells that may have been caused by unnoticed “silent strokes.” (…)

Another study also published by the journal Neurology this week suggested that certain vitamins and a low-trans-fat diet may help preserve memory loss.

The researchers found that trans fat (found in fried and many processed foods) contributed to “more shrinkage of the brain” in addition to less cognitive recognition.

{ Neon Tommy | Continue reading }

brain, food, drinks, restaurants, health | December 31st, 2011 11:50 am

Intense emotional experiences frequently occur with bodily sensations such as a rapid heart rate or gastrointestinal distress.

It appears that bodily sensation (interoception) can be an important source of information when judging one’s emotional. How the brain processes interoception is becoming better understood.

However, how the brain integrates interoceptive signals with other brain emotional processing circuits is less well understood.

Terasawa and colleagues from Japan recently presented results of their research on this interaction of interoception and emotion.

{ Brain Posts | Continue reading }

photo { Matthew Genitempo }

brain, science | December 15th, 2011 10:50 am

Scientists at the University of Sheffield believe decision making mechanisms in the human brain could mirror how swarms of bees choose new nest sites.

Striking similarities have been found in decision making systems between humans and insects in the past but now researchers believe that bees could teach us about how our brains work.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

bees, brain | December 12th, 2011 1:02 pm

Depressed people aside, the rest of us underestimate the likelihood that bad things will happen to us and overestimate the likelihood of good outcomes. Asked to imagine positive scenarios, we do so with greater vividness and more immediacy than when asked to picture negative occurrences - our images of those are hazy and distant.

Now Tali Sharot and her colleagues have investigated the brain mechanisms underlying this rosy outlook. (…)

One key finding is that the participants showed a bias in the way that they updated their estimates, being much more likely to revise an original estimate that was overly pessimistic than to revise an original estimate that was unduly optimistic. (…)

“Our findings offer a mechanistic account of how unrealistic optimism persists in the face of challenging information,” said Sharot and her team. “We found that optimism was related to diminished coding of undesirable information about the future in a region of the frontal cortex (right inferior frontal gyrus) that has been identified as being sensitive to negative estimation errors.”

{ BPS | Continue reading }

brain, psychology | December 7th, 2011 6:40 am

Sit back, close your eyes, relax for a minute and allow your mind to wander wherever it wants to go. Don’t try to think of anything… Have you ever wondered what is going on inside your brain when your mind isn’t doing anything in particular, just like a moment ago? It turns out quite a lot.

One of the most astonishing qualities of the brain is its voracious appetite for energy. It accounts for only 2% of body weight, yet it burns an amazing 20% of the total calories consumed by the body. So you might think that the brain at rest would be conserving energy until the next task, but this is hardly the case. The energy consumption of the brain at rest decreases by only 5% compared to a brain at full capacity. Scientists have named the energy consumed during rest the brain’s “dark energy,” since the massive energy consumption during this so-called rest period is one of the biggest mysteries in neuroscience today.

{ BrainBlogger | Continue reading }

screenshot { Marley Shelton in Robert Rodriguez’s Planet Terror, 2007 }

brain, neurosciences | November 23rd, 2011 2:06 pm

…suggesting that brains have two distinct molecular learning mechanisms, one to learn about relationships among events in the world around them, and one to learn about the effects of their own behavior on the world.

{ Bjoern Brembs | Continue reading }

brain, ideas, science | November 15th, 2011 4:56 pm

According to a new paper, the brains of male-to-female transexuals are no more “female” than those of men. (…) But is it so simple? (..)

Structural MRI scans were used to compare the size of various brain structures between three groups of volunteers: heterosexual men, heterosexual women and the transexuals (or “MtF”s as I will call them for short) who were diagnosed with gender dysphoria and were “genetically and phenotypically males”.

There were 24 in each group, which makes it a decent sized study. None of the MtFs had started hormone treatment yet, so that wasn’t a factor, and none of the women were on hormonal contraception.

The scans showed that the non-transsexual male and female brains differed in various ways. Male brains were larger overall but women had increases in the relative volumes of various areas. Male brains were also more asymmetrical.

The key finding was that on average, the MtF brains were not like the female ones. There were some significant differences from the male brains, but they weren’t the same differences that distinguished the females from the males. (…)

There could be all kinds of chemical and microstructural differences that don’t show up on these scans.

There are lots of people with severe epilepsy, for example, whose brains clearly differ in some major way from people without epilepsy, yet they look completely normal on MRI.

{ Neuroskeptic | Continue reading }

photo { Bruce Davidson }

brain, genders | November 9th, 2011 3:40 am