‘A pair of powerful spectacles has sometimes sufficed to cure a person in love.’ –Nietzsche

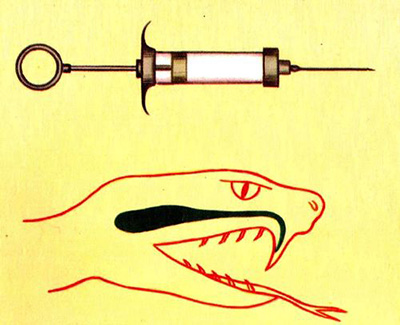

The brain systems that modulate “that loving feeling” are only just beginning to be understood, but neuroscience research is pointing more and more to the idea that the sensation of love relies on the same brain circuitry that goes awry in addiction. Love is a drug, basically — because only a drive as strong as an addiction could keep couples together through the stresses of parenting and keep parents tied to their kids.

Research has found, for example, that people in love are similar to those suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder — not only in terms of their obsessive thinking and compulsive behavior, but also the low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in their blood. So in a sense, love may be a special case of addiction

“The bottom line is that a lot of data on people rejected in love show that the major pathways linked with addiction become activated,” says Helen Fisher, a biological anthropologist at Rutgers University. If love is a drug, however, love’s chemistry can be chemically manipulated — those who are in love but don’t want to be could potentially take a pill that simply makes the formerly loved one seem no more special than a stranger.

“Love hurts”—as the saying goes—and a certain amount of pain and difficulty in intimate relationships is unavoidable. Sometimes it may even be beneficial, since adversity can lead to personal growth, self-discovery, and a range of other components of a life well-lived.

But other times, love can be downright dangerous. It may bind a spouse to her domestic abuser, draw an unscrupulous adult toward sexual involvement with a child, put someone under the insidious spell of a cult leader, and even inspire jealousy-fueled homicide. […]

Modern neuroscience and emerging developments in psychopharmacology open up a range of possible interventions that might actually work. These developments raise profound moral questions about the potential uses—and misuses—of such anti-love biotechnology. In this article, we describe a number of prospective love-diminishing interventions, and offer a preliminary ethical framework for dealing with them responsibly should they arise.