psychology

Does playing hard to get work?

‘Easy things nobody wants, but what is forbidden is tempting.’ –Ovid

Back in the 60s and 70s, before the sexual revolution had really taken hold, the standard dating advice for women was play hard to get. In some quarters it still is.

Like the Roman poet Ovid 2,000 years earlier, social scientists in the 1960s accepted the cultural lore that women could increase their desirability by being coy. When interviewed, men seemed to agree: they said that hard to get women were probably more popular, beautiful and had better personalities.

Unfortunately every time psychologists used an experiment to test the idea that playing hard to get is a good dating strategy, their results didn’t make any sense. At least not until 1973 when Elaine Walster and colleagues at the University of Wisconsin finally hit upon a method that teased out the subtleties. (…)

So this experiment suggests that playing hard to get only works in the sense that it signals selectivity. But for the person you are after, you should be easy to get because otherwise they’ll assume you’re hard work.

In the light of this experiment we can remix Ovid’s quote to: “Easy things are tempting, but only if they are forbidden to others.”

{ PsyBlog | Continue reading }

illustration { Imp Kerr & Associates, 2010 }

related { Abdi Assadi, Relationship as Yoga 1 & 2 | Podcast | iTunes }

psychology, relationships | April 15th, 2010 7:48 am

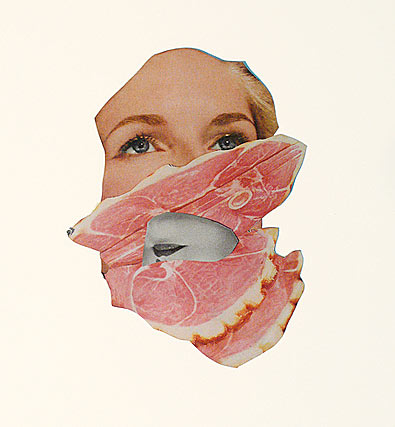

Is the happy life characterized by shallow, happy-go-lucky moments and trivial small talk, or by reflection and profound social encounters? Both notions—the happy ignoramus and the fulfilled deep thinker—exist, but little is known about which interaction style is actually associated with greater happiness (King & Napa, 1998). In this article, we report findings from a naturalistic observation study that investigated whether happy and unhappy people differ in the amount of small talk and substantive conversations they have. (…)

Naturally, our correlational findings are causally ambiguous. On the one hand, well-being may be causally antecedent to having substantive interactions; happy people may be “social attractors” who facilitate deep social encounters (Lucas & Dyrenforth, 2006). On the other hand, deep conversations may actually make people happier. (…)

Remarking on Socrates’ dictum that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” Dennett (1984) wrote, “The overly examined life is nothing to write home about either” (p. 87). Although we hesitate to enter such delicate philosophical disputes, our findings suggest that people find their lives more worth living when examined―at least when examined together.

{ Psychological Science | Continue reading }

collage { never always }

ideas, psychology, relationships | April 15th, 2010 7:45 am

When pain is pleasant

Ever prodded at an injury despite the fact you know it will hurt? Ever cook an incredibly spicy dish even though you know your digestive tract will suffer for it? If the answers are yes, you’re not alone. Pain is ostensibly a negative thing but we’re often drawn to it. Why?

According to Marta Andreatta from the University of Wurzburg, it’s a question of timing. After we experience pain, the lack of it is a relief. Andreatta thinks that if something happens during this pleasurable window immediately after a burst of pain, we come to associate it with the positive experience of pain relief rather than the negative feeling of the pain itself. The catch is that we don’t realise this has happened. We believe that the event, which occurred so closely to a flash of pain, must be a negative one. But our reflexes betray us.

Andreatta’s work builds on previous research with flies and mice. If flies smell a distinctive aroma just before feeling an electric shock, they’ll learn to avoid that smell. However, if the smell is released immediately after the shock, they’re actually drawn to it. Rather than danger, the smell was linked with safety. The same trick works in mice. But what about humans?

{ Discover magazine | Continue reading }

quote { Charles Baudelaire, The Man Who Tortures Himself, 1857 }

psychology, science, uh oh | April 15th, 2010 7:40 am

{ A new study suggests that darkness encourages cheating, even when it makes no difference to anonymity. | BPS | full story }

psychology, relationships | April 15th, 2010 7:16 am

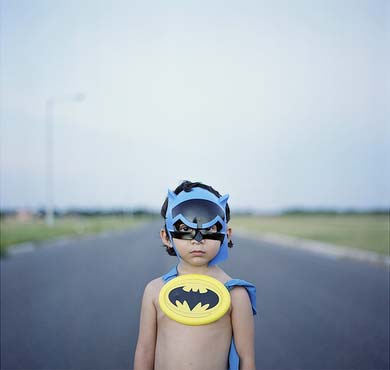

This week, a study found that drinking habits are socially transmissible. Last month, a paper said that both cooperation and selfishness can spread like a virus. In February, a study found that poor sleep and pot smoking are contagious among teens. All of these revelations come from the works of two scientists, Harvard’s Nicholas Christakis and U.C. San Diego’s James Fowler. They first brought fame to contagion in 2007 with a widely publicized paper suggesting that obesity is “socially contagious” and that it can spread like a pox from one friend to another, and then another, and then to one more. More contagions (depression and divorce) are in the works. In their 2009 book, Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives, Christakis and Fowler write that connection and contagion are “the anatomy and physiology of the human superorganism,” and that “everything we think, feel, do, or say can spread far beyond the people we know.”

The studies have provoked excitement in the public health community but also some head-scratching. Many were surprised by the claim that obesity, for example, could be transmitted from one person to another. We thought we knew the major causes of fatness: genes, for one thing, along with eating too many calories and living a sedentary lifestyle. The finding that loneliness can be contagious also caught some readers off-guard

{ Slate | Continue reading }

photo { Bryan Formhals }

psychology | April 14th, 2010 2:26 pm

Would you be happier if you spent more time discussing the state of the world and the meaning of life — and less time talking about the weather?

It may sound counterintuitive, but people who spend more of their day having deep discussions and less time engaging in small talk seem to be happier, said Matthias Mehl, a psychologist at the University of Arizona who published a study on the subject.

“We found this so interesting, because it could have gone the other way — it could have been, ‘Don’t worry, be happy’ — as long as you surf on the shallow level of life you’re happy, and if you go into the existential depths you’ll be unhappy,” Dr. Mehl said.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

photo { Laura Taylor }

ideas, leisure, psychology | March 20th, 2010 9:00 am

Is mental illness good for you?

Mental illness is surprisingly common. About 10% of the population is affected by it at any one time and up to 25% suffer some kind of mental illness over their lifetime. This has led some people (many people in fact) to surmise that it must exist for a reason – in particular that it must be associated with some kind of evolutionary advantage. Indeed, this is a popular and persistent idea both in scientific circles and in the general public.

Such theories come in two main varieties – the first, that mental illness confers some specific advantage to those afflicted; and second, that the mutations which cause mental illness in one person’s genetic background may confer an advantage when they are in a different genetic background (balancing selection).

{ Wiring the brain | Continue reading }

health, ideas, psychology, science | March 18th, 2010 2:40 pm

When people think of knowledge, they generally think of two sorts of facts: facts that don’t change, like the height of Mount Everest or the capital of the United States, and facts that fluctuate constantly, like the temperature or the stock market close.

But in between there is a third kind: facts that change slowly. These are facts which we tend to view as fixed, but which shift over the course of a lifetime. For example: What is Earth’s population? I remember learning 6 billion, and some of you might even have learned 5 billion. Well, it turns out it’s about 6.8 billion. (…)

These slow-changing facts are what I term “mesofacts.” Mesofacts are the facts that change neither too quickly nor too slowly, that lie in this difficult-to-comprehend middle, or meso-, scale. (…)

Updating your mesofacts can change how you think about the world. Do you know the percentage of people in the world who use mobile phones? In 1997, the answer was 4 percent. By 2007, it was nearly 50 percent.

{ The Boston Globe | Continue reading }

photo { Daemian and Christine }

psychology, time | March 18th, 2010 2:30 pm

Can psychiatry be a science?

You arrive for work and someone informs you that you have until five o’clock to clean out your office. You have been laid off. At first, your family is brave and supportive, and although you’re in shock, you convince yourself that you were ready for something new. Then you start waking up at 3 A.M., apparently in order to stare at the ceiling. (…) After a week, you have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning. After two weeks, you have a hard time getting out of the house. You go see a doctor. The doctor hears your story and prescribes an antidepressant. Do you take it?

However you go about making this decision, do not read the psychiatric literature. Everything in it, from the science (do the meds really work?) to the metaphysics (is depression really a disease?), will confuse you. There is little agreement about what causes depression and no consensus about what cures it.

{ The New Yorker | Continue reading }

photo { Ujin Lee Dust }

experience, health, incidents, psychology, science | March 18th, 2010 2:22 pm

Can a clean smell make you a better person?

That’s the provocative suggestion of a recent study in the journal Psychological Science. A team of researchers found that when people were in a room recently spritzed with a citrus-scented cleanser, they behaved more fairly when playing a classic trust game. In another experiment, the smell of cleanser made subjects more likely to volunteer for a charity.

The findings suggest that simply smelling something clean makes people clean up their behavior - that a smell can provoke a mental leap between cleanliness and morality, making people think differently about the world around them. The authors even suggested that clean smells could be employed as a tool to influence how people act.

The idea that a smell can affect something as complex as ethical behavior seems surprising, not least because smell has long been seen as a “lower” sense, playing on our emotions and instincts while our reason and judgment operate on another plane. But research increasingly shows that smell doesn’t just affect how we feel: It affects how we think, in ways that are just beginning to be understood.

{ The Boston Globe | Continue reading }

One of the works that helps visualize the breakthrough is a painting done in 1961, which consists in a greatly enlarged version of a simple black-and-white advertisement of the kind that appears in side columns and back pages of cheap newspapers. It advertised the services of a plastic surgeon, and showed two profiles of the same woman, before and after an operation on her nose.

{ NY Times | Continue reading }

artwork { Andy Warhol, Before and After, 1961 }

olfaction, psychology, science, warhol | March 17th, 2010 4:48 pm

As long as we’re on the topic of impulsivity, a brief remark about the word ‘manipulative,’ which I’ve found to be a remarkably overused, overrated explanation for the behavior of inflexible-explosive children. To me, the act of manipulation requires a fair amount of forethought, planning, affective modulation, and calculation — qualities that are in short supply in the vast majority of the inflexible-explosive children I know. Given that few of us enjoy being manipulated, believing that a child is being manipulative often causes adults to behave in counterproductive ways and hinders their consideration of more accurate explanations.

{ Ross Greene, The Explosive Child, 1998 | Thanks Blue M.! }

ideas, kids, psychology | March 11th, 2010 4:50 pm

How to tell if a guy is trustworthy?

Men with wider faces are not only perceived as untrustworthy, they may deserve the reputation, according to a new study published in the journal Psychological Science. (…)

A growing body of science is showing that facial configuration — placement of the eyes, width of the cheekbones and so on — provides clues to a person’s personality, including likelihood to be extroverted, conscientious and, now, trustworthy. While this analysis is not unfailing, it works slightly more often than not.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading }

psychology, relationships, science | March 11th, 2010 4:47 pm

psychology, sport | March 11th, 2010 4:46 pm

{ Why do we believe, and are atheists really more intelligent? | Artwork: Andrea Mantegna, Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, 1470-75 }

beaux-arts, psychology | March 11th, 2010 4:44 pm

Paradoxically we initially like narcissists more because of their exploitative, entitled behaviour—but it doesn’t last long. (…)

There are all sorts of paradoxes in the way narcissists behave. Here are three that this research helps explain:

1. Why do people continue to behave selfishly when it only ruins their relationships with others?

2. Why do narcissists devalue others when they are so dependent on them for admiration?

3. Why don’t narcissists spot the cycle of early attraction followed by rejection?

The first two are partly explained by the fact that narcissistic behaviour is, at first, attractive to other people. Behaving selfishly seems to bring them a rush of admiration which they get addicted to, while devaluing others when the inevitable rejection comes, covering it up by searching out new people to worship them.

The reason narcissists fail to spot this cycle may well be that friends and partners never hang around long enough to tell them in such a way that they actually believe it and want to do something about it.

{ PsyBlog | Continue reading }

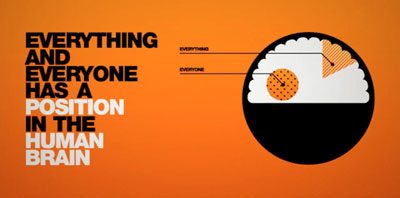

graphic design { Casper Sormani }

psychology, weirdos | March 4th, 2010 6:00 pm

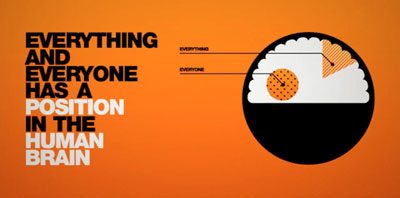

Psychologists have used an inventive combination of techniques to show that the left half of the brain has more self-esteem than the right half. The finding is consistent with earlier research showing that the left hemisphere is associated more with positive, approach-related emotions, whereas the right hemisphere is associated more with negative emotions.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

Iain McGilchrist has recently published ‘The Master and his Emissary’ a book which posits that the division of the brain into two hemispheres is essential to human existence, making possible incompatible versions of the world, with quite different priorities and values.

{ Interview | Frontier Psychiatrist | Continue reading }

illustration { Kristian Hammerstad }

brain, halves-pairs, psychology | March 3rd, 2010 5:41 pm

It’s with some courage that Melanie Glenwright and Penny Pexman have chosen to investigate the tricky issue of when exactly children learn the distinction between sarcasm and irony. Their finding is that nine- to ten-year-olds can tell the difference, although they can’t yet explicitly explain it. Four- to five-year-olds, by contrast, understand that sarcasm and irony are non-literal forms of language, but they can’t tell the difference between the two.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

photo { Mando Alvarez }

kids, psychology | February 25th, 2010 8:51 pm

motorpsycho, psychology, weirdos | February 25th, 2010 8:44 pm

Graduates prefer cats. According to press reports of research at the University of Bristol, households with graduates are 36 per cent more likely to have cats than their academically uninstructed counterparts. Most reports attribute the difference to discrepant brain power. “Clever people are more likely to own cats than dogs,” says the Press Association version of the findings.

The newspapers have diffused the same message. Jane Murray, who led the research, is credited with a rival explanation: “It could be related to longer working hours,” which leave graduates with less time to care for pets than the implicitly idle dog-lovers. (…)

I like cats. (…) The real difference between cat-lovers and dog-lovers has nothing to do with income, education or habits of work. It is, I suspect, a matter of morals. Dog-lovers are good. Cat-lovers are morally indifferent or actively evil.

{ Times Higher Education | Continue reading }

animals, psychology | February 25th, 2010 8:42 pm

An old Greek fable famously tells the story of a fox, who tries really hard to get his hands on a tasty vine of grapes. The fox tries and he tries, but eventually fails in all of his attempts to acquire the grapes; at which point the fox calmly continues with his life by convincing himself that he really didn’t want those grapes that badly after all…

Although there is a common wisdom in this tale of how we deal with being thwarted in our desires, a more modern psychological account of the fox’s tale may look a little different: i.e. if the fox in our tale had been reading today’s psychological journals he may have concluded, more precisely, that had he continued in his efforts, and finally obtained the grapes, THEN he may not have liked them as much.

To see why the fox may have concluded this, we must first consider that from a physiological (and pharmacological) perspective, wanting something and liking something do not necessarily go hand-in-hand, and that they certainly aren’t the same thing. For example, a drug addict really, really wants her fix, but many addicts genuinely report not particularly liking their subsequent drugged out experiences. Additionally, a number of psychological studies show that liking and wanting can be independently manipulated, and that often times both operate at a subconscious level.

{ Daniel R Hawes | Continue reading }

ideas, psychology | February 25th, 2010 8:35 pm