brain

In a stunning discovery that overturns decades of textbook teaching, researchers at the University of Virginia School of Medicine have determined that the brain is directly connected to the immune system by vessels previously thought not to exist. That such vessels could have escaped detection when the lymphatic system has been so thoroughly mapped throughout the body is surprising on its own, but the true significance of the discovery lies in the effects it could have on the study and treatment of neurological diseases ranging from autism to Alzheimer’s disease to multiple sclerosis.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

unrelated { The benefits of a herpes infection }

blood, brain, health | June 2nd, 2015 1:18 pm

Ageing causes changes to the brain size, vasculature, and cognition. The brain shrinks with increasing age and there are changes at all levels from molecules to morphology. Incidence of stroke, white matter lesions, and dementia also rise with age, as does level of memory impairment and there are changes in levels of neurotransmitters and hormones. Protective factors that reduce cardiovascular risk, namely regular exercise, a healthy diet, and low to moderate alcohol intake, seem to aid the ageing brain as does increased cognitive effort in the form of education or occupational attainment. A healthy life both physically and mentally may be the best defence against the changes of an ageing brain. Additional measures to prevent cardiovascular disease may also be important. […]

It has been widely found that the volume of the brain and/or its weight declines with age at a rate of around 5% per decade after age 40 with the actual rate of decline possibly increasing with age particularly over age 70. […]

The most widely seen cognitive change associated with ageing is that of memory. Memory function can be broadly divided into four sections, episodic memory, semantic memory, procedural memory, and working memory.18 The first two of these are most important with regard to ageing. Episodic memory is defined as “a form of memory in which information is stored with ‘mental tags’, about where, when and how the information was picked up”. An example of an episodic memory would be a memory of your first day at school, the important meeting you attended last week, or the lesson where you learnt that Paris is the capital of France. Episodic memory performance is thought to decline from middle age onwards. This is particularly true for recall in normal ageing and less so for recognition. It is also a characteristic of the memory loss seen in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). […]

Semantic memory is defined as “memory for meanings”, for example, knowing that Paris is the capital of France, that 10 millimetres make up a centimetre, or that Mozart composed the Magic Flute. Semantic memory increases gradually from middle age to the young elderly but then declines in the very elderly.

{ Postgraduate Medical Journal | Continue reading | Thanks Tim}

brain, health, memory | May 17th, 2015 2:49 pm

Scientists are increasingly convinced that the vast assemblage of microfauna in our intestines may have a major impact on our state of mind. The gut-brain axis seems to be bidirectional—the brain acts on gastrointestinal and immune functions that help to shape the gut’s microbial makeup, and gut microbes make neuroactive compounds, including neurotransmitters and metabolites that also act on the brain. […]

Microbes may have their own evolutionary reasons for communicating with the brain. They need us to be social, says John Cryan, a neuroscientist at University College Cork in Ireland, so that they can spread through the human population. Cryan’s research shows that when bred in sterile conditions, germ-free mice lacking in intestinal microbes also lack an ability to recognize other mice with whom they interact. In other studies, disruptions of the microbiome induced mice behavior that mimics human anxiety, depression and even autism. In some cases, scientists restored more normal behavior by treating their test subjects with certain strains of benign bacteria. Nearly all the data so far are limited to mice, but Cryan believes the findings provide fertile ground for developing analogous compounds, which he calls psychobiotics, for humans. “That dietary treatments could be used as either adjunct or sole therapy for mood disorders is not beyond the realm of possibility,” he says.

{ Scientific American | Continue reading }

related { Is Neuroscience Based On Biology? }

brain, food, drinks, restaurants, neurosciences | March 10th, 2015 1:05 pm

Individuals who report experiencing communication with deceased persons are traditionally called mediums. During a typical mediumship reading, a medium conveys messages from deceased persons to the living (i.e., sitters). There are two types of mediumship: mental and physical. In mental mediumship, communication with deceased persons is experienced “through interior vision or hearing, or through the spirits taking over and controlling their bodies or parts thereof, especially … the parts required for speech and writing.” During physical mediumship, the experienced communication “proceeds through paranormal physical events in the medium’s vicinity,” which have included reports of independent voices, rapping sounds on walls or tables, and movement of objects. […]

Recent research has also confirmed previous findings that mediumship is not associated with conventional dissociative experiences, pathology, dysfunction, psychosis, or over-active imaginations. Indeed, a large percentage of mediums have been found to be high functioning, socially accepted individuals within their communities. […]

Psychometric and brain electrophysiology data were collected from six individuals who had previously reported accurate information about deceased individuals under double-blind conditions. Each experimental participant performed two tasks with eyes closed.

In the first task, the participant was given only the first name of a deceased person and asked 25 questions. After each question, the participant was asked to silently perceive information relevant to the question for 20 s and then respond verbally. Responses were transcribed and then scored for accuracy by individuals who knew the deceased persons. Of the four mediums whose accuracy could be evaluated, three scored significantly above chance (p < 0.03). The correlation between accuracy and brain activity during the 20 s of silent mediumship communication was significant in frontal theta for one participant (p < 0.01).

In the second task, participants were asked to experience four mental states for 1 min each: (1) thinking about a known living person, (2) listening to a biography, (3) thinking about an imaginary person, and (4) interacting mentally with a known deceased person. Each mental state was repeated three times. Statistically significant differences at p < 0.01 after correction for multiple comparisons in electrocortical activity among the four conditions were obtained in all six participants, primarily in the gamma band (which might be due to muscular activity). These differences suggest that the impression of communicating with the deceased may be a distinct mental state distinct from ordinary thinking or imagination.

{ Frontiers in Psychology | PDF }

brain, psychology | February 9th, 2015 12:32 pm

A car accident, the loss of a loved one and financial trouble are just a few of the myriad stressors we may encounter in our lifetimes. Some of us take it in stride, while others go on to develop anxiety or depression. How well will we deal with the inevitable lows of life?

A clue to this answer, according to a new Duke University study, is found in an almond-shaped structure deep within our brains: the amygdala. By measuring activity of this area, which is crucial for detecting and responding to danger, researchers say they can tell who will become depressed or anxious in response to stressful life events, as far as four years down the road.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | February 5th, 2015 1:40 pm

[T]he patient was a woman who, although she was being examined in my office at New York Hospital, claimed we were in her home in Freeport, Maine. The standard interpretation of this syndrome is that she made a duplicate copy of a place (or person) and insisted that there are two. […]

This woman was intelligent; before the interview she was biding her time reading the New York Times. I started with the ‘So, where are you?’ question. ‘I am in Freeport, Maine. I know you don’t believe it. Dr Posner told me this morning when he came to see me that I was in Memorial Sloan-Kettering Hospital. […] Well, that is fine, but I know I am in my house on Main Street in Freeport, Maine!’ I asked, ‘Well, if you are in Freeport and in your house, how come there are elevators outside the door here?’

The grand lady peered at me and calmly responded, ‘Doctor, do you know how much it cost me to have those put in?’ […]

Because of her lesion the part of the brain that represents locality is overactive and sending out an erroneous message about her location. The interpreter is only as good as the information it receives, and in this instance it is getting a wacky piece of information.

{ NeuroDojo | Continue reading }

brain, housing | November 15th, 2014 1:19 pm

University of Washington researchers have successfully replicated a direct brain-to-brain connection between pairs of people. […] Researchers were able to transmit the signals from one person’s brain over the Internet and use these signals to control the hand motions of another person within a split second of sending that signal.

{ University of Washington | Continue reading }

brain | November 6th, 2014 1:44 pm

Have you ever felt lost and alone? If so, this experience probably involved your hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure in the middle of the brain. About 40 years ago, scientists with electrodes discovered that some neurons in the hippocampus fire each time an animal passes through a particular location in its environment. These neurons, called place cells, are thought to function as a cognitive map that enables navigation and spatial memory.

Place cells are typically studied by recording from the hippocampus of a rodent navigating through a laboratory maze. But in the real world, rats can cover a lot of ground. For example, many rats leave their filthy sewer bunkers every night to enter the cozy bedrooms of innocent sleeping children.

In a recent paper, esteemed neuroscientist Dr. Dylan Rich and colleagues investigated how place cells encode very large spaces. Specifically, they asked: how are new place cells recruited to the network as a rat explores a truly giant maze?

{ Sick papes | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | October 7th, 2014 6:03 am

A woman has reached the age of 24 without anyone realising she was missing a large part of her brain. […] The discovery was made when the woman was admitted to the Chinese PLA General Hospital of Jinan Military Area Command in Shandong Province complaining of dizziness and nausea. She told doctors she’d had problems walking steadily for most of her life, and her mother reported that she hadn’t walked until she was 7 and that her speech only became intelligible at the age of 6.

Doctors did a CAT scan and immediately identified the source of the problem – her entire cerebellum was missing. The space where it should be was empty of tissue. Instead it was filled with cerebrospinal fluid, which cushions the brain and provides defence against disease.

The cerebellum – sometimes known as the “little brain” – is located underneath the two hemispheres. It looks different from the rest of the brain because it consists of much smaller and more compact folds of tissue. It represents about 10 per cent of the brain’s total volume but contains 50 per cent of its neurons. […]

The cerebellum’s main job is to control voluntary movements and balance, and it is also thought to be involved in our ability to learn specific motor actions and speak.

{ NewScientist | Continue reading }

brain | September 11th, 2014 2:18 pm

Damage to certain parts of the brain can lead to a bizarre syndrome called hemispatial neglect, in which one loses awareness of one side of their body and the space around it. In extreme cases, a patient with hemispatial neglect might eat food from only one side of their plate, dress on only one side of their body, or shave or apply make-up to half of their face, apparently because they cannot pay attention to anything on that the other side.

Research published last week now suggests that something like this happens to all of us when we drift off to sleep each night.

{ Neurophilosophy/Guardian | Continue reading }

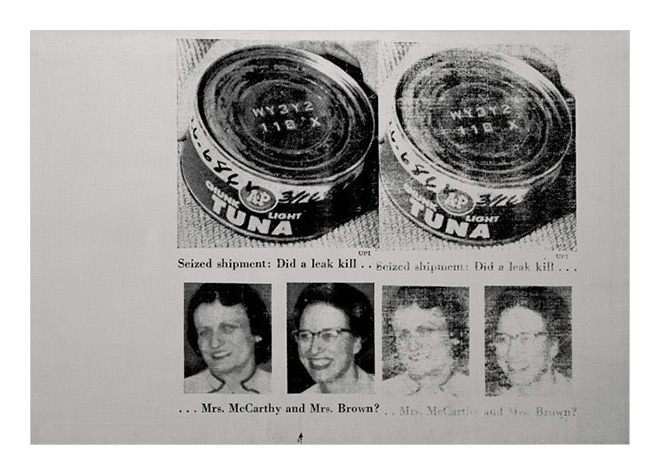

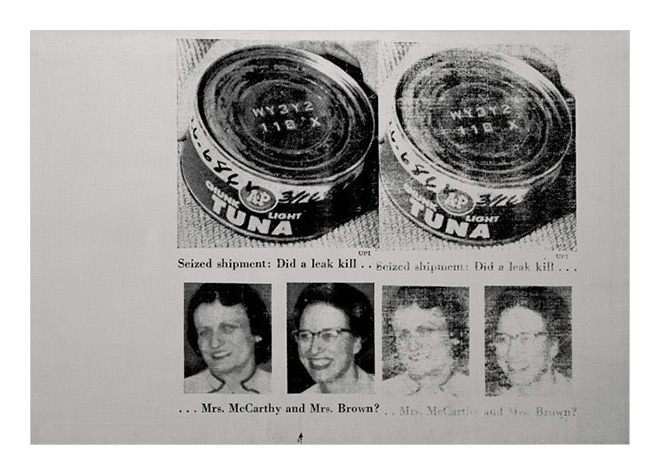

art { Andy Warhol, Mrs. McCarthy and Mrs. Brown (Tunafish Disaster), (1963) }

brain, sleep, warhol | June 9th, 2014 1:01 pm

It is just possible to discern some points beneath the heated rhetoric in which Patricia Churchland indulges. But none of these points is right. If you hold that “mental processes are actually processes in the brain,” to quote Churchland, then you are committed to the thesis that it is sufficient to understand the mind that one understands the brain, and not merely necessary. This is just the well-known “identity theory” of mind and brain: mental processes are identical to brain processes; and the identity of a with b entails the sufficiency of a for b. To hold the weaker thesis that knowledge of the brain is merely necessary for knowledge of the mind is consistent even with being a heavy-duty Cartesian dualist, since even such a dualist accepts that mind depends causally on brain.

{ Patricia Churchland vs. Colin McGinn/NY Review of Books | Continue reading }

brain, controversy | June 1st, 2014 6:59 am

“Neuroreductionism” is the tendency to reduce complex mental phenomena to brain states, confusing correlation for physical causation. In this paper, we illustrate the dangers of this popular neuro-fallacy, by looking at an example drawn from the media: a story about “hypoactive sexual desire disorder” in women. We discuss the role of folk dualism in perpetuating such a confusion, and draw some conclusions about the role of “brain scans” in our understanding of romantic love.

{ Savulescu & Earp | Continue reading }

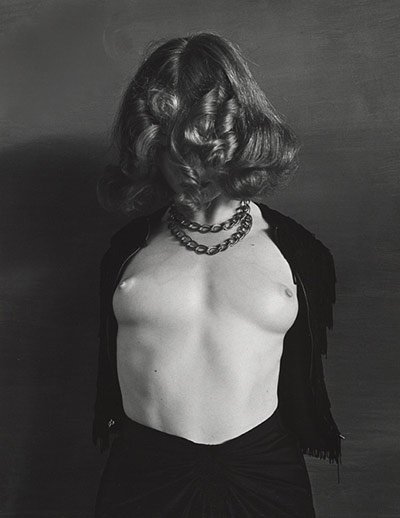

photo { John Gutmann, Naked Breasts, Covered Face, 1939 }

brain, neurosciences, relationships | May 15th, 2014 2:33 pm

At one end is our everyday consciousness, and at the other is total unconsciousness, as represented by coma. Actually, the term “coma” covers two very similar states: One is the kind of coma that results from a severe head injury or cardiac arrest, and the other is the state induced in a hospital setting by means of general anesthesia.

So anyone who has had general anesthesia has been in a coma?

Yes, general anesthesia is nearly identical to what we might call “natural” coma.

{ American Scientist | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | March 22nd, 2014 11:00 am

“Saying there are differences in male and female brains is just not true. There is pretty compelling evidence that any differences are tiny and are the result of environment not biology,” said Prof Rippon.

“You can’t pick up a brain and say ‘that’s a girls brain, or that’s a boys brain’ in the same way you can with the skeleton. They look the same.” […]

A women’s brain may therefore become ‘wired’ for multi-tasking simply because society expects that of her and so she uses that part of her brain more often. The brain adapts in the same way as a muscle gets larger with extra use.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading }

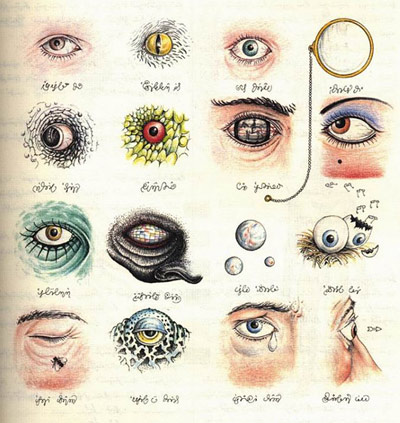

photo { John Gutmann, Freaky Faces Graffiti (Masks Graffiti), San Francisco, 1939 }

brain, genders, neurosciences | March 9th, 2014 4:48 am

A current theory regarding language functions is that women use both hemispheres more equally, whereas men are more strongly lateralized to the left hemisphere. This theory is supported by fMRI and PET studies, but the strongest evidence is that after lesions to the left hemisphere men more often develop aphasia than women.

{ Wikipedia | Continue reading }

screenshot { Robert Bresson, Au hasard Balthazar, 1966 }

brain, genders | January 26th, 2014 4:00 pm

Girls’ brains can begin maturing from the age of 10 while some men have to wait until 20 before the same organisational structures take place, Newcastle University scientists have found.

{ Telegraph | Continue reading }

Men who have daughters also grow less attached to traditional gender roles: they become less likely to agree with the statement that “a woman’s place is in the home,” for instance, and more likely to agree that men should wash dishes and do other chores. Having a sister, however, has the opposite effect, making men more supportive of traditional gender roles, more conservative politically, and less likely to perform housework.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

brain, genders | December 20th, 2013 7:14 am

Specifically, they reported that men’s brains had more connectivity within each brain hemisphere, whereas women’s brains had more connectivity across the two hemispheres. Moreover, they stated or implied, in their paper and in statements to the press, that these findings help explain behavioral differences between the sexes, such as that women are intuitive thinkers and good at multi-tasking whereas men are good at sports and map-reading. […]

So, the wiring differences between the sexes aren’t that large. And we don’t really know their functional significance, if any. […]

[L]et’s set this new brain wiring study in the context of previous research. Verma and her team admit that a previous paper looking at the brain wiring of 439 participants failed to find significant differences between the sexes. What about studies on the corpus callosum – the thick bundle of fibres that connects the two brain hemispheres? If women really have more cross-talk across the brain, this is one place where you’d definitely expect them to have more connectivity. And yet a 2012 diffusion tensor paper found “a stronger inter-hemispheric connectivity between the frontal lobes in males than females”. Hmm. Another paper from 2006 found little difference in thickness of the callosum according to sex. Finally a meta-analysis from 2009: “The alleged sex-related corpus callosum size difference is a myth,” it says.

{ Wired | Continue reading }

A small sample of the more credulous media uptake:

“Male and female brains wired differently, scans reveal”, The Guardian 12/2/2013

“Striking differences in brain wiring between men and women”, EarthSky 12/3/2013

“Is Equal Opportunity Threatened By New Findings That Female And Male Brains Are Different?”, Forbes 12/3/2013

”The hardwired difference between male and female brains could explain why men are ‘better at map reading’ and why women are ‘better at remembering a conversation’”, The Independent 12/3/2013

”Sex and Brains: Vive la différence!”, The Economist 12/7/2013

“Differences in How Men and Women Think Are Hard-Wired”, WSJ 12/9/2013

“Brains of women, men are actually wired differently”, New Scientist 12/12/2013

“Gender differences are hard-wired”, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review 12/15/2013

Some more thoughtful reactions:

“Study: The Brains of Men and Women Are Different… WIth A Few Major Caveats”, Forbes 12/8/2013

“Do Men And Women Have Different Brains?”, NPR 12/13/2013

“Time to ditch the ‘Venus and Mars’ cliche”, The New Zealand Herald 12/14/2013

{ Language Log | Continue reading }

art { Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Sylvette David in Green Chair, 1954 }

brain, genders, neurosciences | December 16th, 2013 8:06 am

Our brains perceive objects in everyday life of which we may never be aware, a study finds, challenging currently accepted models about how the brain processes visual information. […]

“There’s a brain signature for meaningful processing,” Sanguinetti said. A peak in the averaged brainwaves called N400 indicates that the brain has recognized an object and associated it with a particular meaning.

“It happens about 400 milliseconds after the image is shown, less than a half a second,” said Peterson. “As one looks at brainwaves, they’re undulating above a baseline axis and below that axis. The negative ones below the axis are called N and positive ones above the axis are called P, so N400 means it’s a negative waveform that happens approximately 400 milliseconds after the image is shown.”

The presence of the N400 peak indicates that subjects’ brains recognize the meaning of the shapes on the outside of the figure.

“The participants in our experiments don’t see those shapes on the outside; nonetheless, the brain signature tells us that they have processed the meaning of those shapes,” said Peterson. “But the brain rejects them as interpretations, and if it rejects the shapes from conscious perception, then you won’t have any awareness of them.”

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading }

brain, neurosciences | November 13th, 2013 4:22 pm

There is a motif, in fiction and in life, of people having wonderful things happen to them, but still ending up unhappy. We can adapt to anything, it seems—you can get your dream job, marry a wonderful human, finally get 1 million dollars or Twitter followers—eventually we acclimate and find new things to complain about.

If you want to look at it on a micro level, take an average day. You go to work; make some money; eat some food; interact with friends, family or co-workers; go home; and watch some TV. Nothing particularly bad happens, but you still can’t shake a feeling of stress, or worry, or inadequacy, or loneliness.

According to Dr. Rick Hanson, a neuropsychologist, our brains are naturally wired to focus on the negative, which can make us feel stressed and unhappy even though there are a lot of positive things in our lives. True, life can be hard, and legitimately terrible sometimes. Hanson’s book (a sort of self-help manual grounded in research on learning and brain structure) doesn’t suggest that we avoid dwelling on negative experiences altogether—that would be impossible. Instead, he advocates training our brains to appreciate positive experiences when we do have them, by taking the time to focus on them and install them in the brain. […]

The simple idea is that we we all want to have good things inside ourselves: happiness, resilience, love, confidence, and so forth. The question is, how do we actually grow those, in terms of the brain? It’s really important to have positive experiences of these things that we want to grow, and then really help them sink in, because if we don’t help them sink in, they don’t become neural structure very effectively. So what my book’s about is taking the extra 10, 20, 30 seconds to enable everyday experiences to convert to neural structure so that increasingly, you have these strengths with you wherever you go. […]

As our ancestors evolved, they needed to pass on their genes. And day-to-day threats like predators or natural hazards had more urgency and impact for survival. On the other hand, positive experiences like food, shelter, or mating opportunities, those are good, but if you fail to have one of those good experiences today, as an animal, you would have a chance at one tomorrow. But if that animal or early human failed to avoid that predator today, they could literally die as a result.

That’s why the brain today has what scientists call a negativity bias.[…] For example, negative information about someone is more memorable than positive information, which is why negative ads dominate politics. In relationships, studies show that a good, strong relationship needs at least a 5:1 ratio of positive to negative interactions.

{ The Atlantic | Continue reading }

photo and pill bottles { Richard Kern }

brain, guide, psychology | October 25th, 2013 10:27 am

Neurons communicate using electrical signals. They transmit these signals to neighboring cells via special contact points known as synapses. When new information needs processing, the nerve cells can develop new synaptic contacts with their neighboring cells or strengthen existing synapses. To be able to forget, these processes can also be reversed. The brain is consequently in a constant state of reorganization, yet individual neurons need to be prevented from becoming either too active or too inactive. The aim is to keep the level of activity constant, as the long-term overexcitement of neurons can result in damage to the brain.

Too little activity is not good either. “The cells can only re-establish connections with their neighbors when they are ‘awake’, so to speak, that is when they display a minimum level of activity”, explains Mark Hübener, head of the study. The international team of researchers succeeded in demonstrating for the first time that the brain is able to compensate even massive changes in neuronal activity within a period of two days, and can return to an activity level similar to that before the change. […]

In their study, they examined the visual cortex of mice that recently went blind. As expected, but never previously demonstrated, the activity of the neurons in this area of the brain did not fall to zero but to half of the original value. […] After just a few hours, they could clearly observe how the contact points between the affected neurons and their neighboring cells increased in size. When synapses get bigger, they also become stronger and signals are transmitted faster and more effectively. As a result of this synaptic upscaling, the activity of the affected network returned to its starting value after a period of between 24 and 48 hours.

{ Wired Cosmos | Continue reading }

photo { John Swannell }

brain, neurosciences | October 18th, 2013 1:22 pm