Rare lamps with faint rainbow fans

It seems to me that MFA programs have become a tool of indoctrination that has had an unprecedented homogenizing effect on artistic practices worldwide, an effect that is now being replicated with curatorial and critical writing programs. […]

The market of art is not merely a bunch of dealers and cigar-smoking connoisseurs trading exquisite objects for money behind closed doors. Rather, it is a vast and complex international industry of overlapping institutions which jointly produce artworks’ economic value and support a wide range of activities and occupations including training, research, development, production, display, documentation, criticism, marketing, promotion, financing, historicizing, publishing, and so forth. The standardization of art greatly simplifies all of these transactions. For a few years now I have experienced a certain sense of déjà vu while walking through art fairs or biennials, a feeling that many other people have also commented on: that we have already seen all these works that are supposedly brand new. We are experiencing the impact of contemporary art as a globally traded commodity that is produced, displayed, and circulated by an industry of specially trained professionals. […] This is not a new observation: I think Marcel Duchamp already fully understood this danger a hundred year ago. […]

Today it would be rather futile to try to reconstitute bohemia—the free-flowing, organic creative space—because it never really existed within the constellation of institutions of art, the art market, and the art academy. If Warhol’s Factory was an entry into art that enabled a group of people of very different backgrounds to enter a certain kind of productive modality (both within and in spite of the surrounding economy), it was a space of free play that no longer exists. Instead, what we have now are MFA programs: a standardization not even of bohemia, but only its promise. […]

As artists, curators, and writers, we are increasingly forced to market ourselves by developing a consistent product, a concise presentation, a statement that can be communicated in thirty seconds or less—and oftentimes this alone passes for professionalism.

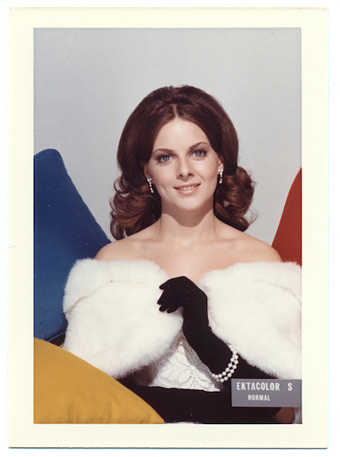

photo { Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin }