The lions couchant on the pillars as he passed out through the gate; toothless terrors. Still I will help him in his fight.

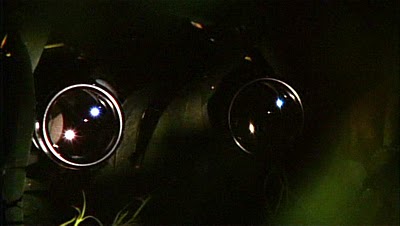

The darkness was like nothing I’d ever seen. I couldn’t see my hand in front of my face; after a while I could barely believe that my hand was there, in front of my face, waving.

That darkness is what I think about when I think of black. I was going to write, the color black, but as every child knows black isn’t a color. Black is a lack, a void of light. When you think about it, it’s surprising that we can see black at all: our eyes are engineered to receive light; in its absence, you’d think we simply wouldn’t see, any more than we taste when our mouths are empty. Black velvet, charcoal black, Ad Reinhart’s black paintings, black-clad Goth kids with black fingernails: how do we see them?

According to modern neurophysiology, the answer is that photoreceptors in our retinas respond to photons of light, and we see black in those areas of the retina where the photoreceptors are relatively inactive. But what happens when no photoreceptors are working—as happens in a cave? Here we turn to Aristotle, who notes that sight, unlike touch or taste, continues to operate in the absence of anything visible:

Even when we are not seeing, it is by sight that we discriminate darkness from light, though not in the same way as we distinguish one colour from another. Further, in a sense even that which sees is coloured; for in each case the sense-organ is capable of receiving the sensible object without its matter. That is why even when the sensible objects are gone the sensings and imaginings continue to exist in the sense-organs.

We “see” in total darkness because sight itself has a color, Aristotle suggests, and that color is black: the feedback hum that lets us know the machine is still on.