A few million dollars doesn’t move the needle for me

If you know that a public company has done a bad thing, and no one else knows about it, how can you use that knowledge to make money? […]

This is a financial column, so we tend to focus on the financial-markets answers: You can short the company’s stock, or buy put options, or buy credit-default swaps. Then you can either sit back and let the market discover the bad thing, or you can bring it to the market’s attention, by announcing the bad thing and maybe also by taking some extra steps—generally suing or calling up a regulator—to get the ball rolling. This approach has some crucial advantages; most notably, if the company is very big and the thing is very bad, this is a good way to make a whole lot of money. But there are disadvantages too. You tend to need a lot of capital to make a lot of money doing this; if you don’t have enough money to make a big bet against the company, you’ll probably have to sell your idea to a hedge fund that does, and you’ll get only a portion of the upside. There are all the general financial risks of short selling: The stock could go up for reasons unrelated to the bad thing, “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent,” etc. There are the specific risks of noisy short selling: The company will accuse you of fraud, people won’t believe your revelations because you have money at stake, etc. There is also the risk of insider trading: Depending on how you came to know of the secret bad thing, there may be some legal risk to you from trading on it.

But those are just the markets-y ways to make money from misbehavior. There are also lots of lawyer-y ways. There are whistleblower programs that can reward you for telling regulators—particularly the Securities and Exchange Commission—about the bad thing. (The SEC’s program focuses on securities fraud, of course, but everything is securities fraud so you can be creative.) If you are a lawyer looking to profit from the bad thing, you can find a victim of the bad thing and sue for damages (and take a cut), or you can find holders of the company’s securities and sue for securities fraud (and take a bigger cut), because, again, everything is securities fraud. […]

The really long game, if you are a lawyer, is that you can become a federal prosecutor, investigate the company for misconduct, push it to hire a fancy law firm staffed with former federal prosecutors to conduct an expensive internal investigation, and enter into a non-prosecution agreement that requires the company to pay millions of dollars to an outside monitor who is also a former federal prosecutor. Do a few of these—expanding the scope of criminal liability for corporations, and normalizing the notion that corporations should resolve their criminal liability by hiring ex-prosecutors as monitors and investigators—and then leave for a private law firm where you get paid to do the investigations and the monitoring, while the next generation of prosecutors creates business for you. […]

Avenatti clearly did not do a good enough job of making the extortion look like something else to satisfy prosecutors. I don’t know if he did enough to satisfy a jury; perhaps we’ll find out. But he didn’t do nothing; the complaint contains some gestures in the direction of Avenatti being a legitimate lawyer with a legitimate case from a legitimate client trying to reach a legitimate settlement. He didn’t just ask for money; he demanded that Nike do an internal investigation and that he be in charge of it. (And be paid a lot.) It’s not pure, naked blackmail; it is a settlement negotiation that gets a little deeper into blackmail territory than you’d ideally like. But any settlement negotiation is, you know, “give me money or I will sue and that will be embarrassing for you,” so it is a matter of degrees.

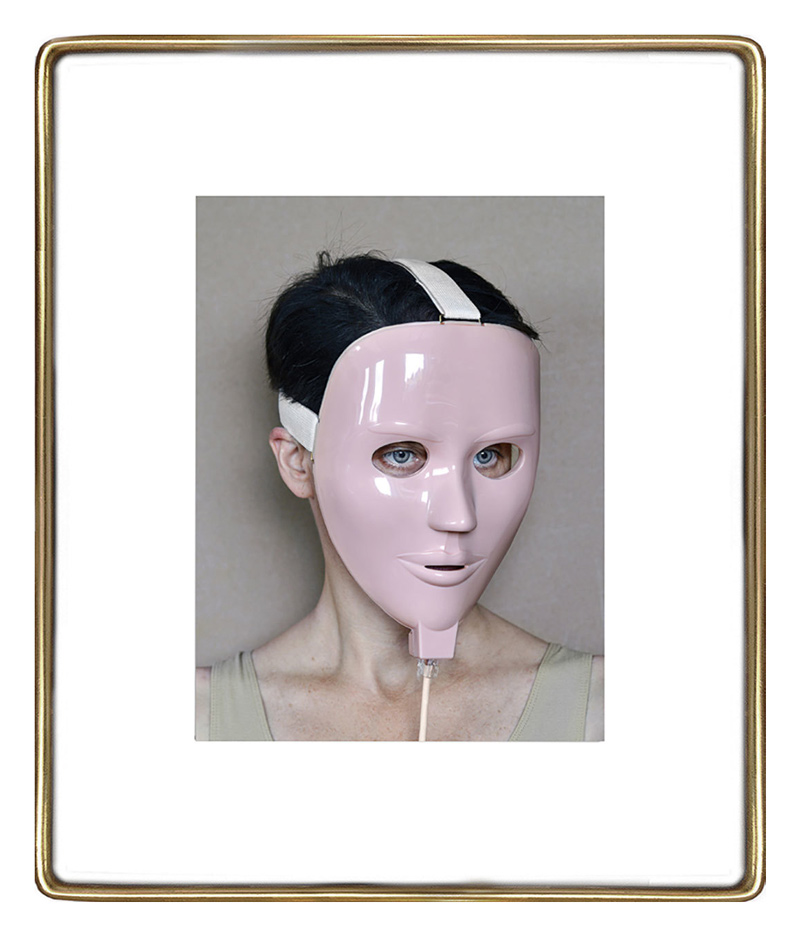

pigment ink on cotton paper { Aneta Grzeszykowska, Beauty Mask #10, 2017 }