Alone on deck, in dark alpaca, yellow kitefaced

One in four of us will struggle with a mental illness this year, the most common being depression and anxiety. The upcoming publication of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) will expand the list of psychiatric classifications, further increasing the number of people who meet criteria for disorder. But will this increase in diagnoses really mean more people are getting the help they need? And to what extent are we pathologising normal human behaviours, reactions and mood swings?

The revamping of the DSM – an essential tool for mental health practitioners and researchers alike, often referred to as the ‘psychiatry bible’ – is long overdue; the previous version was published in 1994. This revision provides an excellent opportunity to scrutinise what qualifies as psychiatric illness and the criteria used to make these diagnoses. But will the experts make the right calls?

The complete list of new diagnoses was released recently and included controversial disorders such as ‘excessive bereavement after a loss’ and ‘internet use gaming disorder’. The inclusion of these syndromes raises the important question of what actually qualifies as pathology.

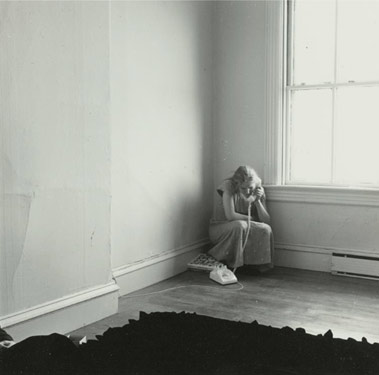

photo { Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island (Self-portrait on the telephone), 1975-1976 }