Ghost illusion created in the lab

On June 29, 1970, mountaineer Reinhold Messner had an unusual experience. Recounting his descent down the virgin summit of Nanga Parbat with his brother, freezing, exhausted, and oxygen-starved in the vast barren landscape, he recalls, “Suddenly there was a third climber with us… a little to my right, a few steps behind me, just outside my field of vision.”

It was invisible, but there. Stories like this have been reported countless times by mountaineers, explorers, and survivors, as well as by people who have been widowed, but also by patients suffering from neurological or psychiatric disorders. They commonly describe a presence that is felt but unseen, akin to a guardian angel or a demon. Inexplicable, illusory, and persistent.

Olaf Blanke’s research team at EPFL has now unveiled this ghost. The team was able to recreate the illusion of a similar presence in the laboratory and provide a simple explanation. They showed that the “feeling of a presence” actually results from an alteration of sensorimotor brain signals, which are involved in generating self-awareness by integrating information from our movements and our body’s position in space.

{ EurekAlert | Continue reading | more }

neurosciences |

November 6th, 2014

University of Washington researchers have successfully replicated a direct brain-to-brain connection between pairs of people. […] Researchers were able to transmit the signals from one person’s brain over the Internet and use these signals to control the hand motions of another person within a split second of sending that signal.

{ University of Washington | Continue reading }

brain |

November 6th, 2014

Researchers at the MIT are testing out their version of a system that lets them see and analyze what autonomous robots, including flying drones, are “thinking.” […]

The system is a “spin on conventional virtual reality that’s designed to visualize a robot’s ‘perceptions and understanding of the world,’” Ali-akbar Agha-mohammadi, a post-doctoral associate at MIT’s Aerospace Controls Laboratory, said in a statement.

{ LiveScience | Continue reading | via gettingsome }

image { Lygia Clark }

robots & ai |

November 6th, 2014

photogs, press, psychology |

November 5th, 2014

Why do we dream? It’s still a scientific mystery. The “Threat Simulation Theory” proposes that we dream as a way to simulate real-life threats and prepare ourselves for dealing with them. “This simulation in an almost-real experiential world would train the brain to perceive dangers and rapidly face them within the safe condition of sleeping,” write the authors of a new paper that’s put the theory to the test. […]

The researchers contacted thousands of first-year students at the end of the day that they sat a very important exam. […] over 700 of the students agreed to participate and they completed a questionnaire about their dreams and sleep quality the previous evening, and any dreams they’d had about the exam over the course of the university term. […] The more exam dreams a student reported having during the term, the higher their grade tended to be.

{ BPS | Continue reading }

collage { Eugenia Loli }

evolution, psychology, sleep |

November 4th, 2014

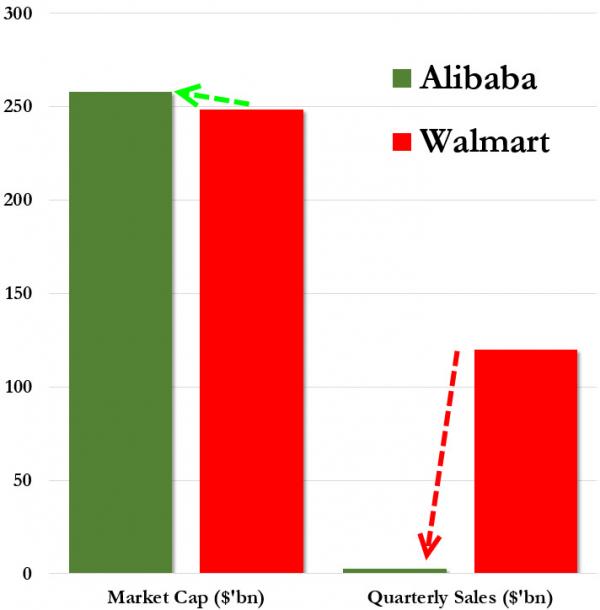

Studying the satellite launch industry, Madsen and Desai (2010) find that the probability of a successful future launch increases with the cumulative number of failed launches.

KC, Staats, and Gino (2013) find almost exactly the opposite at the individual level, showing that individual surgeons future success is positively influenced by their past cumulative number of successes and negatively by their past cumulative number of failures. While a surgeon’s future success rate is negatively correlated with his or her cumulative number of failures, it is positively correlated with the cumulative number of failures of other surgeons in the same hospital. […]

While the exact channels vary from context to context, the empirical literature is clear: individuals and organizations learn from failure, be it their own or the failure of others. […]

[M]any failures go unreported and their lessons are lost.

{ Victor Bennett/Jason Snyder | Continue reading }

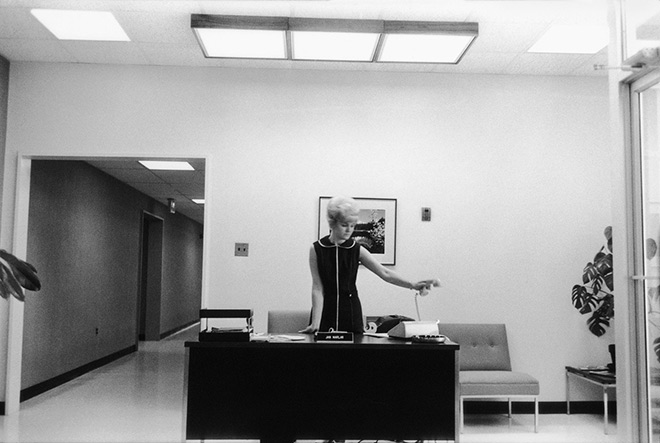

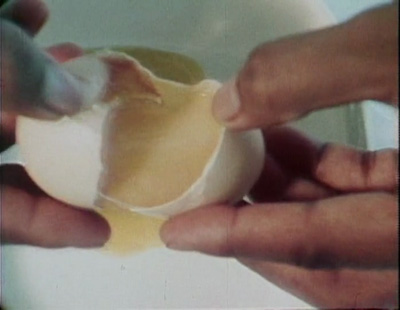

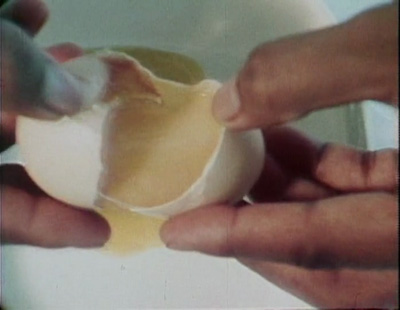

photo { William Eggleston, Untitled, 1960 }

economics |

November 3rd, 2014

In species where females mate with multiple males, the sperm from these males must compete to fertilise available ova. Sexual selection from sperm competition is expected to favor opposing adaptations in males that function either in the avoidance of sperm competition (by guarding females from rival males) or in the engagement in sperm competition (by increased expenditure on the ejaculate). […]

We found that men who performed fewer mate guarding behaviors produced higher quality ejaculates, having a greater concentration of sperm, a higher percentage of motile sperm and sperm that swam faster and less erratically.

{ PLoS | Continue reading }

related { Britain’s sperm shortage - and the man who helps two women a month | via gettingsome }

relationships, science, sex-oriented |

November 2nd, 2014

In the mirror we see our physical selves as we truly are, even though the image might not live up to what we want, or what we once were. But we recognize the image as “self.” In rare instances, however, this reality breaks down. […]

How can the recognition of self in a mirror break down?

There are at least seven main routes to dissolution or distortion of self-image:

1. psychotic disorders

2. dementia

3. right parietal-ish or otherwise right posterior cortical strokes and lesions

4. the ‘strange-face in the mirror’ illusion

5. hypnosis

6. dissociative disorders (e.g., depersonalization, dissociative identity disorder

7. body image issues (e.g., anorexia, body dysmorphic disorder)

{ The Neurocritic | Continue reading }

The strange-face-in-the-mirror illusion […] a never-before-described visual illusion where your own reflection in the mirror seems to become distorted and shifts identity. […] To trigger the illusion you need to stare at your own reflection in a dimly lit room. […] The participant just has to gaze at his or her reflected face within the mirror and usually “after less than a minute, the observer began to perceive the strange-face illusion.”

{ Mind Hacks | Continue reading }

faces, psychology |

October 30th, 2014

People can make remarkably accurate judgments about others in a variety of situations after just a brief exposure to their behavior. Ambady and Rosenthal (1992) referred to this brief observation as a “thin slice.” For example, students could accurately predict personality traits of an instructor after watching a 30-s video clip […] a 2-s look at a picture of a face was enough to accurately determine a violent or nonviolent past. Other research has demonstrated the predictive accuracy of short observations regarding social status, psychopathy, and socioeconomic status. […]

The data indicate that this ability to predict outcomes from brief observations is more intuitive than deliberatively cognitive, leading scholars to believe that the ability to accurately predict is “hard-wired and occur[s] relatively automatically.” […]

The viability of using brief observations of behavior (thin slicing) to identify infidelity in romantic relationships was examined. […] In Study 1, raters were able to accurately identify people who were cheating on their romantic dating partner after viewing a short 3- to 4-min video of the couple interacting.

{ Personal Relationships | Continue reading }

related { Thin-Slicing Divorce: Thirty Seconds

of Information Predict Changes in Psychological Adjustment Over 90 Days | PDF }

psychology, relationships |

October 30th, 2014

Sicily, for instance, employs 950 ambulance drivers who have no ambulances to drive

Sicily, for instance, employs 950 ambulance drivers who have no ambulances to drive

Men who had slept with more than 20 women lowered their risk of developing cancer by almost one third. In contrast, men who slept with 20 men doubled their risk of developing prostate cancer.

Swimming is the individual activity that most people would drop if they faced higher prices

Brain scans show cause of winter blues

Virgin birth has been documented in the world’s longest snake for the first time

there might be a way to determine whether your horse wants a blanket or prefers to be naked

The Case of the Brooklyn Enigma, Part One and Part Two

Experts have severely underestimated the risks of genetically modified food, says a group of researchers lead by Nassim Nicholas Taleb In 2013 roughly 85 per cent of corn and 90 per cent of soybeans produced in the US were genetically modified.

On Fraud, Ignorance, and Lying: Essays in Behavioral Business Ethics

In 2015, most leading Web browsers will be set to support what are known as push notifications.

When Plato gave Socrates’ definition of man as “featherless bipeds” and was much praised for the definition, Diogenes plucked a chicken and brought it into Plato’s Academy, saying, “Behold! I’ve brought you a man.” After this incident, “with broad flat nails” was added to Plato’s definition.

Windowless plane set for take off in a decade

RKO compilation [Thanks Tim]

every day the same again |

October 28th, 2014

Miniature “human brains” have been grown in a lab in a feat scientists hope will transform the understanding of neurological disorders.

{ BBC | Continue reading | Thanks Tim }

science, weirdos |

October 28th, 2014

Here, a group of nine chefs and three scientists is pushing the boundaries in the most minimalist, nuanced way, part of an effort to ensure that this ultimate “slow food” remains relevant in a fast-paced world. The chefs are tinkering with a way of cooking that has remained unchanged for centuries.

First, […] the chefs played around with the temperature at which they steamed abalone. Received wisdom says it should be steamed at 212 degrees Fahrenheit, or the boiling point of water, for two hours. […] So they spent six months — yes, six months — steaming abalone, changing the temperature in tiny increments. “It turned out that even two degrees had a huge impact on its deliciousness,” Fushiki said in his university office. The perfect temperature to steam an abalone, they concluded, is between 140 and 148 degrees, depending on how it is used. […]

The second six-month period was devoted to coagulation. Not content with coagulating food, they experimented with coagulating air. “How can we make the smell of air?” Fushiki recalled the chefs asking. “Let’s whisk and make bubbles, so that each bubble contains the air, and the smell spreads when the bubbles pop.”

{ Washington Post | Continue reading }

food, drinks, restaurants |

October 27th, 2014

Selecting an appropriate mate is arguably one of the most important decisions that any sexually reproducing animal must make in order to ensure the successful propagation of their genes. […]

It has been proposed that kissing, a near-ubiquitous custom among human cultures, may play a significant role in the process of human mate assessment and relationship maintenance. Kissing might aid mate appraisal in humans by facilitating olfactory assessment of various cues for genetic compatibility, health, genetic fitness, or even menstrual cycle phase and fertility. […]

Recent research into kissing behavior among college students has found interesting differences between men and women in their perceptions of the importance of kissing during various courtship and mating situations. Using self-report measures, it was found that men generally placed less emphasis on kissing than women, and that women placed greater value on kissing during both the early stages of courtship, potentially as a mate assessment device, and in the later stages of a long-term relationship, possibly to maintain and monitor the pair-bonds that underlie such relationships. […]

The aim of the present experiment was to determine whether romantic kissing-related information can affect the process of human mate assessment. It was hypothesized that participants led to believe that a potential mating partner is a “good kisser,” a manifest cue potentially signaling a mate’s underlying genetic quality/suitability, will find them more attractive, will be more willing to pursue further courtship (i.e., a date) with them, will be more interested in pursuing non-committal sex with them, and be more willing to consider pursuing a long-term relationship with them. It was further hypothesized that alleged kissing abilities will have a greater influence on female partner preferences than on male partner preferences, as they have been found to be the more selective sex when it comes to utilizing signals of mate fitness. […]

The primary finding of this study is that purported kissing abilities can influence a potential mate’s attractiveness and general desirability, particularly for women in casual sex situations. […] Although the findings presented here corroborate the notion that kissing serves a functional role in mating situations, we can still only speculate at this point as to the mechanisms by which kissing might carry out these functions. It is likely that kissing works to affect initial mate assessment by bringing two individuals into close proximity so as to facilitate some kind of olfactory/gustatory assessment, since olfaction in most mammals, as well as in humans, can play an important role in assessing potential mates. In established relationships, on the other hand, the contact and physiological arousal initiated by continued romantic kissing is likely to also affect feelings of attachment between individuals over time, influencing the release of neuropeptides (including oxytocin and vasopressin), dopamine, and opioids, which have all been variously associated with human pair-bonding.

{ Evolutionary Psychology | PDF }

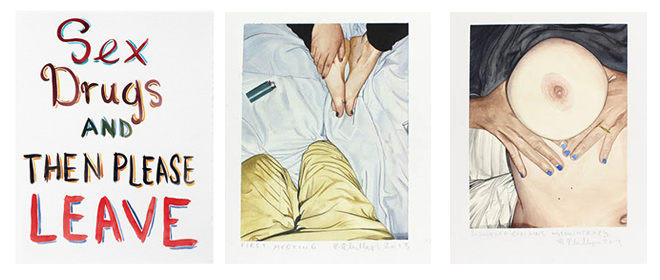

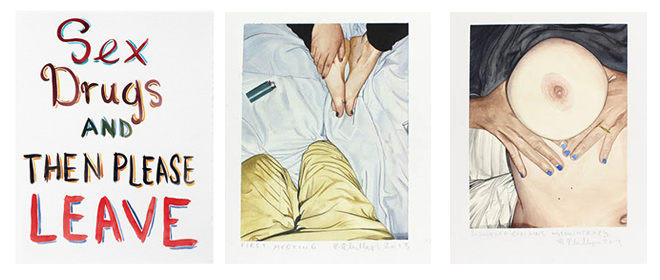

watercolor on paper { Brad Phillips }

psychology, relationships |

October 25th, 2014

Harvard scientists have discovered a new way to fight brain cancer with stem cells, a recent study has revealed.

The team of scientists, who experimented on mice, used genetically engineered stem cells that released cancer killing toxins, while leaving healthy cells unaffected.

Most importantly, the modified cells were able to emit the tumour killing poison without succumbing to its effects.

It is considered a breakthrough in cancer treatment by experts.

{ Independent | ScienceDaily }

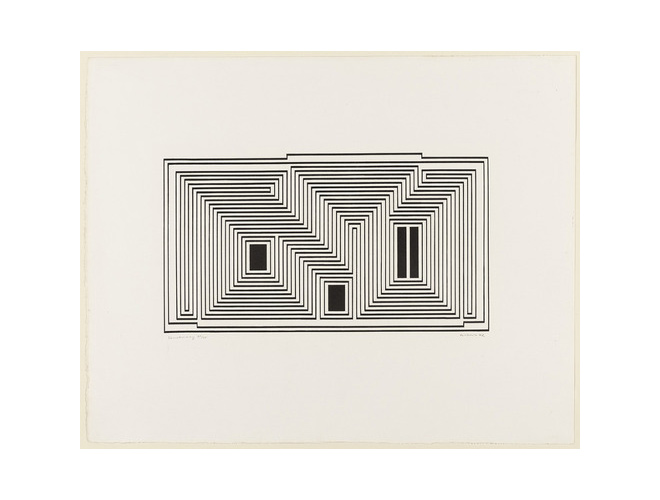

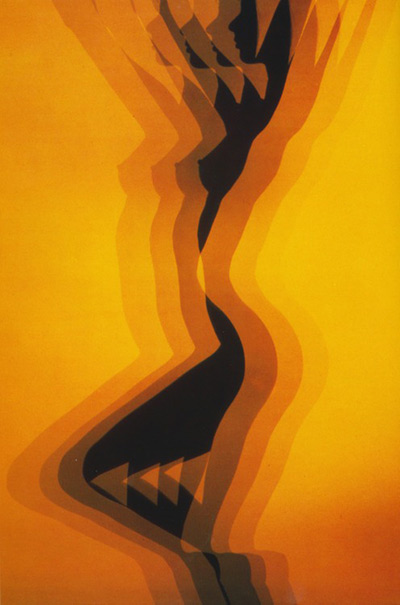

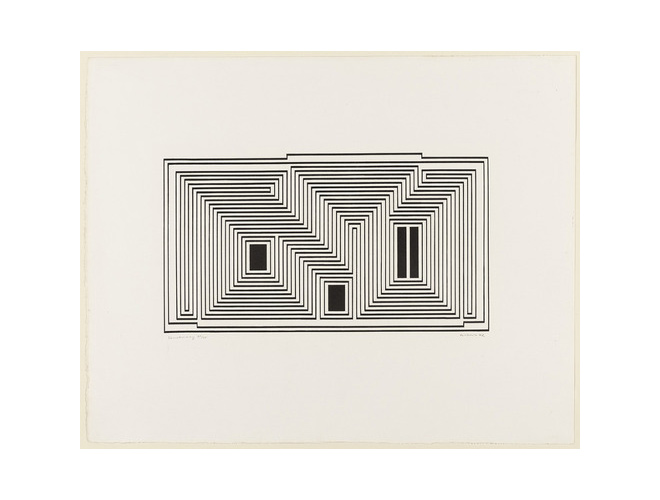

art { Josef Albers, Sanctuary, 1942 }

health, stem cells |

October 25th, 2014

Pham and Schackelford (2013) argued that men with more attractive partners are at a greater recurrent risk of sperm competition because other men are more likely to woo them into having affairs. Therefore, men with more attractive partners have more reason to be concerned about and more likely to engage in behaviour aimed to detect infidelity. The idea that cunnilingus, oral sex performed on a woman, could function to detect infidelity was proposed in a 2006 book, but this study is the first to test this empirically. The idea is that oral sex may allow a man to detect the presence of another man’s semen through smell or taste. […]

As side-note I’d like to point out that there is a common misconception often advanced by its critics that evolutionary psychology assumes that everything that people do is somehow an evolutionary adaptation and that evolutionary psychologists cannot or will not acknowledge that some behaviours are simply by-products of other adaptations with no special function of their own. This is a gross misrepresentation of what evolutionary psychology is about and in fairness to the authors of the study they were attempting to actually test whether or not their hypothesis about the adaptive function of oral sex is valid, rather than just assuming it is. It is quite possible that oral sex has no evolutionary function in itself. Humans are a highly sexed species compared to most mammals and engage in many non-procreative sexual acts, perhaps for pleasure alone. Oral sex might simply be a by-product of this interest in sex that humans have. However, if it can be shown that this particular behaviour appears to serve a definite purpose that has an evolutionary history, a reasonable case can be made that it has an adaptive function. […]

They found that “recurrent risk of sperm competition” (attractiveness) predicted interest in performing oral sex independently of relationship length, relationship satisfaction, and duration of intercourse.

{ Psychology Today | Continue reading }

archives, evolution, relationships, sex-oriented |

October 24th, 2014

Red blood cells carry oxygen to all the cells and tissues in our body. If we lose a lot of blood in surgery or an accident, we need more of it – fast. Hence the hundreds of millions of people flowing through blood donation centres across the world, and the thousands of vehicles transporting bags of blood to processing centres and hospitals.

It would be straightforward if we all had the same blood. But we don’t. On the surface of every one of our red blood cells, we have up to 342 antigens – molecules capable of triggering the production of specialised proteins called antibodies. It is the presence or absence of particular antigens that determines someone’s blood type. […]

If a particular high-prevalence antigen is missing from your red blood cells, then you are ‘negative’ for that blood group. If you receive blood from a ‘positive’ donor, then your own antibodies may react with the incompatible donor blood cells, triggering a further response from the immune system. These transfusion reactions can be lethal. […]

There are 35 blood group systems, organised according to the genes that carry the information to produce the antigens within each system. The majority of the 342 blood group antigens belong to one of these systems. The Rh system (formerly known as ‘Rhesus’) is the largest, containing 61 antigens.

The most important of these Rh antigens, the D antigen, is quite often missing in Caucasians, of whom around 15 per cent are Rh D negative (more commonly, though inaccurately, known as Rh-negative blood). But Thomas seemed to be lacking all the Rh antigens. If this suspicion proved correct, it would make his blood type Rh null – one of the rarest in the world, and a phenomenal discovery for the hospital haematologists. […] Some 43 people with Rh null blood had been reported worldwide.

{ Mosaic | Continue reading }

blood |

October 24th, 2014

In response to a threat, the brain triggers the release of epinephrine and cortisol from your adrenal glands into the blood. As a result, your heart beats faster and stronger, your blood vessels dilate to move more blood, and your lung vessels dilate to exchange more oxygen for carbon dioxide. Equally as important, your liver breaks down glycogen (a sugar storage molecule) to glucose and dumps it into your bloodstream.

All these processes work together to increase your alertness and increase the power of your muscles for a short time — like when mothers who lift cars off their small children. You are now ready to respond to the threat; however, there is an exception — you may do nothing at all.

One of the major control mechanisms of the fight or flight response is the autonomic nervous system. This is part of the peripheral nervous system (PNS, outside the brain and spinal cord) and transmits information from the central nervous system to the rest of the body. The autonomic system controls involuntary movements and some of the functions of organs and organ systems.

Parts of the autonomic system acts like a teeter-totter, it’s their relative balance that controls the outcomes. In the fight or flight response, the sympathetic system predominates and your heart rate increases and your blood vessels dilate.

But what if the parasympathetic system gained an upper hand for a short time? […] The heart slows, the blood vessels constrict in the muscles, blood moves from muscles to the gut, and glycogen is produced from glucose. […] Many people have had the experience of parasympathetic domination coincident to a threat, for some folks it proceeds long enough to have an observable result – they faint. […] when your brain is starved of oxygen and glucose, you pass out. […]

Lower animals will faint as well, but they have additional defenses along these lines. Mammals, amphibians, insects and even fish can be scared enough to fake death. […] There are overlapping mechanisms for feigned death, from tonic immobility (not moving) to thanatosis (thanat = death, and osis = condition of, playing dead). […] One study in crickets showed that those who feigned death the longest were more likely to avoid being attacked, so this is definitely a survival adaptation.

{ biological exceptions | Continue reading }

photo { Steven Brahms }

evolution |

October 22nd, 2014